Korakrit Arunanondchai articulates creation myths at Museum MACAN

by Manu SharmaJan 05, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Louis HoPublished on : May 14, 2024

Avant-garde art and sex work have had a curiously entwined history. The demimondaines of 19th century Paris were captured on canvas by the likes of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Edouard Manet, a tradition carried on by Pablo Picasso in the 20th century with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), a misogynistic portrait of brothel denizens in Barcelona. It was in the second half of the 20th century that the iconography of sex work moved into the third dimension with the involvement of sex workers in the flesh, from Suzanne Lacy’s Prostitution Notes (1974), which transformed the artist’s research on Los Angeles’ sex scene into a series of scribbled maps and musings, to Marina Abramovic’s performative switch with an actual working girl in Amsterdam’s red light district (Role Exchange, 1975). The 1970s also saw the first exhibition on the topic of sex work, simply titled Prostitution (1976), organised by the collective, COUM Transmission, at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA)—a history that the ICA celebrated with another show on the same subject, Decriminalised Futures (2022), nearly five decades later.

Like Lacy, artist-academic Kosem’s work is centred on an ethnographic approach to the oldest profession. Kosem is multi-hyphenate: he is a visual artist and an anthropologist and identifies as being Thai, Muslim and queer (not necessarily in that order). His practice, informed by academic research and fieldwork, explores themes of borders and sexuality through visual ethnography, utilising objects, text and video documentation. His project, Nonhuman Ethnography (2017-2022), considers how queerness is embodied in Muslim culture through the contexts of nonhuman entities such as animals and water, while the ongoing Chiang Mai Ethnography: Borders re-make bodies (2019 onwards) examines the lives of male sex workers in northern Thailand who hail from Shan state in neighbouring Myanmar. Currently a PhD candidate at Chiang Mai University, Kosem has been an Erasmus+ exchange fellow at the School of Humanities, Tallinn University, and an artist-in-residence at Delfina Foundation in London.

Louis Ho: You’re wrapping up your PhD work in anthropology at Chiang Mai University, but you’ve had a pretty intense education before that, at an Islamic school. Tell us a little about the path from pondok student to openly queer artist.

Samak Kosem: My family had high hopes for me, so they sent me to study at an Islamic school or pondok in Nonthaburi, north of Bangkok, because there were none in my hometown in Rayong. I began studying religion at the age of 12 until I completed high school, totalling six years. During this time, I had to study books in Arabic and Jawi—an old Austronesian script used in written Malay—because the school was predominantly Malay-Muslim.

During my time there, what I didn't anticipate was the issue of my own sexual identity. This became a central question: how do religious spaces, which often determine gender norms, sometimes become areas where queer relationships can flourish? I then moved into anthropology, which led me to question various aspects of Muslim society in different contexts. An academic article I wrote in 2017, titled Pondan under the Pondok, recounted childhood memories of homosexual behaviour in the pondok. “Pondan”, of course, is a derogatory label in Malay for effete men. Later, when I ventured into making art, I had to find ways to visualise what I had studied and questioned from an anthropological perspective, as the basis for developing my artistic practice.

Louis: Some of your earlier work, such as the Nonhuman Ethnography project (2017–2022), deals with Thai-Muslim identities and lifeworlds, including queer ones, in Thailand’s so-called Deep South. Can you tell us more about that?

Samak: Yes, I began a project in the south on nonhuman subjects in 2017. Pattani is one of the three Muslim provinces in southern Thailand, along with Yala and Narathiwat, that has seen an ongoing separatist struggle. The moving-image piece, Sheep (2017-2018), for instance, examines the interaction between humans and animals; sheep are a common everyday sight in that region. I was thinking of metaphors for the communities of the Deep South within the Thai state and religious violence. The Day I Became… (2018) deals with a queer individual; it tells the story of a tomboy Muslim who left their hometown in Yala to work in Bangkok. Local Muslims often say that there is “no homosexuality in Islam, no gays in our community.” In the southern border regions, people are dehumanised not simply by state-sponsored violence and regulation.

Louis: Your more recent research, though, looks at male sex workers in the north of Thailand, where you have been based for years. Many of these men are ethnic Shan, from Myanmar. Why the interest in sex workers within a particular demographic?

Samak: The Shan are a Thai-speaking ethnic group, and various insurgent Shan armies have been waging war against the Burmese government for decades. My research is a continuation of my previous work in the Deep South—a region also beset by armed separatist violence—which examines the relationship between borders and bodies. It questions how sexuality varies according to shifts in people’s conditions and cultures, and led me to focus on migrants in Chiang Mai. I wanted to look at how masculinity is constructed in the context of border-crossing situations, particularly in the case of Shan men involved in the sex trade. It isn’t just about sex work, or sex tourism, though. My work is informed by, and challenges, ideas of masculinity, transnationality, and queer visuality.

Louis: You have also expanded your research into several bodies of art. Tell us more about that.

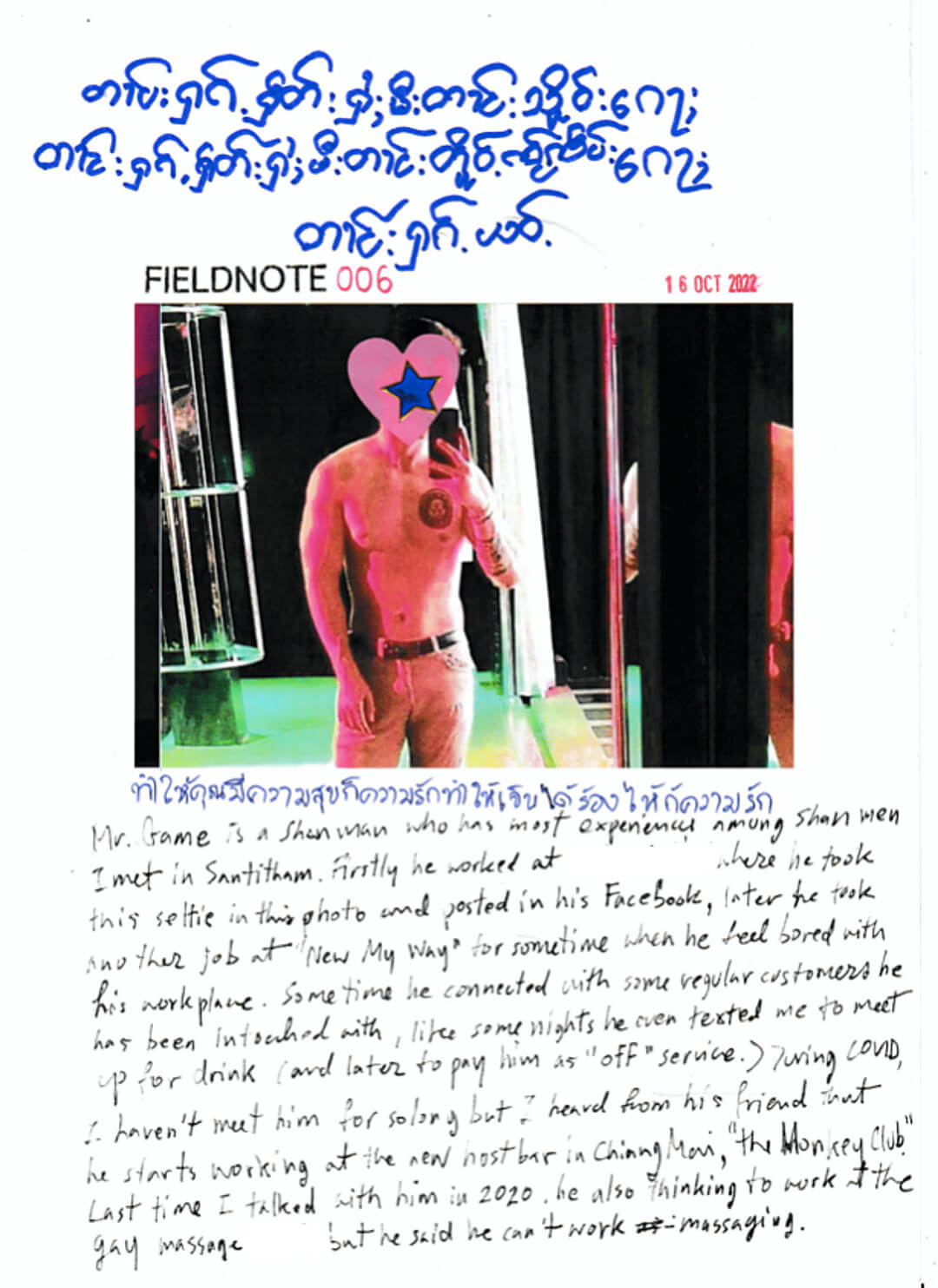

Samak: During the development of my doctoral research, I began creating my first series of artwork as a preliminary exploration (At that time, I received important advice from curator Patrick Flores on presenting issues related to sex work). Chiang Mai Ethnography: Borders re-make bodies was begun in 2019. I experimented with methods beyond anthropological tools, incorporating art-related processes as a means for data collection, providing more opportunities for the subjects in my studies to actively participate in narrating their own stories. The first series of works was exhibited at the Osage Gallery in Hong Kong in 2019 and included three main components: field notes, various objects related to the research, and short documentary videos aimed at conveying subjects’ narratives directly. I term it “visual ethnography”. The work later travelled to exhibitions in different cities, such as Richard Koh Fine Art in Singapore and Vargas Museum UP in Manila.

This body of work is significant in the development of the critical ideas in my dissertation. These works are not meant to be conclusive; rather, they consist of little-heard voices and sub-messages that aim to interconnect and narrate the overarching story in the entire body of work.

Louis: Tell us a little more about the work, and perhaps the individuals you have encountered in the course of your fieldwork.

Samak: I’m concerned with questions of masculinity, which Shan men still see as having a significant impact on their self-image even when engaging in male-to-male sex work. Many seek ways to “man up”. When speaking to them, it seems that ideals of masculinity require them to perform certain roles; being sex workers reflects their sense of responsibility for their families’ economic welfare, a gendered rather than a moral obligation. I once heard the story of a young Shan man who hanged himself – in the Chiang Mai bar he worked in – because he felt belittled by his parents for engaging in such work, even though he was supporting his family back home. It helped me understand the influences on their notions of masculinity, which are not solely determined by nationality and ethnicity. Family, too, is crucial to their lives.

Louis: I’m sure you must have many stories to tell. Could you elaborate on some other defining experiences?

Samak: I was once in Loi Tai Leng, a small town located on the border of northern Thailand and Shan State in Myanmar, to join Tai National Day celebrations there—hoping to encounter a Shan man who used to work in gay bars in Chiang Mai, but who later decided to return to join the army. I had seen a post online from a Shan man claiming to have returned home to perform his duties as a man. The masculinity that is at stake when engaging in sex work in Thailand is redeemed when they return to join the Shan army. In that way, no one questions their masculinity, not even themselves. In Loi Tai Leng, I instead encountered another young man I knew from a different bar, who had also returned to enlist in the army. It was due to economic reasons though; during the pandemic, he had no customers and his income was insufficient. Interestingly, a month after meeting him at the border, he deserted his post and returned to work in a bar in Chiang Mai.

Louis: What’s next for you?

Samak: I’m planning to complete a project on Shan masculinities this year. I am also participating in a residency program in Kaohsiung and while there, I want to look at non-Taiwanese migrants in the city. The idea came to me while sitting at a tea shop in a community of Muslim migrants from Myanmar who had gathered at night. Without my noticing, they disappeared, leaving only their stuff behind. This led me to think: how much can we study the movement or displacement of people based on what they’ve left behind? It's somewhat like taking a backward approach when studying human migration, but I want to try working backwards, from what is discarded.

by Ranjana Dave Oct 03, 2025

Bridging a museum collection and contemporary works, curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath treat ‘yearning’ as a continuum in their plans for the 2025 Taipei Biennial.

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

by Hili Perlson Sep 26, 2025

The exhibition at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus unpacks the politics of taste and social memory embedded in the architecture of the former East Germany.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Louis Ho | Published on : May 14, 2024

What do you think?