Spanning creative spectrums, LDF reveals winners of the 2025 London Design Medals

by Bansari PaghdarSep 09, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Oli MarshallPublished on : Aug 08, 2024

“No one and nothing is perfect - Improvement is the only responsible approach one can take in design as in life.”

- Sir Kenneth Grange (1929-2024)

These were the words of legendary designer Sir Kenneth Grange, who died last month, shortly after his 95th birthday. His work over 70 years helped shape the domestic life and public realm of modern Britain; the way ordinary people cook, create, consume, groom and travel.

While other big-name industrial designers may have attracted a cult following and fawning fandom for product designs defined by a particular aesthetic, Kenneth had no rigid ideology or manifesto. He was guided instead by a curiosity, generosity and a ready wit that endeared him to all. His was a playful take on modernism, which captured something of the eccentricity and innate visual language of the British Isles - “the sculpture of the everyday object”.

Kenneth’s career was unparalleled in its breadth and longevity. Starting as a young draughtsman working on the 1951 Festival of Britain - that great rebirth of the arts industry, in a nation scarred by the Second World War - and continuing well into the 21st century, he was still restlessly designing as a nonagenarian, in the era of AI and net-zero. “If they’re lucky, designers never retire” he once quipped. “There’s nothing in life like being wanted”.

Among his most successful and well-known creations were the streamlined InterCity 125 High Speed Train (examples of which are still in service 40 years after its introduction), the user-friendly Instamatic range of cameras for Kodak (sales of which surpassed 3 million and transformed the photographic brand’s fortunes), countless kitchen appliances for Kenwood, razors for Wilkinson Sword and pens for Parker. These were just some of the 10,000+ products that left his drawing board, many of which genuinely deserve the overused moniker, ‘iconic’. He even found time to co-found Pentagram, in 1971, the first ‘supergroup’ partnership of multidisciplinary designers and template for the modern creative agency.

Adept at imaginatively interpreting a brief, intuitive understanding of user experience and with savvy commerciality, he often developed deep and long-lasting friendships with brands over many decades. One particularly unusual but handy skill he mastered, was the ability to draw upside down – sketching a concept in real time while sitting opposite a client.

Looking at the long arc of Kenneth’s career, if it was the ambition of youth that drove him towards the landmark commissions of the 1960s and '70s, then there was a wisdom and assuredness in his later years that produced perhaps his most interesting work – particularly those projects that sought to reimagine ‘sacred’ classic designs. Creating sleek yet sympathetic new forms for the red rural post-box, and the black London Taxi Cab, re-defining the archetypal 1930s Anglepoise task light (in the process, creating their best-selling product, the Type 75) and fashioning a new wire shopping basket for Boots, the high-street pharmacist, that nods to a traditional wicker basket. All of these required an experienced hand and one with ego firmly in check.

Coming of age in the heady optimism and utopianism of the post-war era, Kenneth was never attracted to the luxury end of the design sector that has recently predominated, preferring to plough an aspirational yet accessible furrow, in what was a booming age for consumer goods. He once decried the Financial Times’ How to Spend It supplement as “offensive” and commented that the modern design industry is “as much entertainment as it is anything else”. Yet the controversies were few, in a career that endured through changing styles and transcended passing trends.

Knighted in 2013 for services to design, he was the recipient of numerous awards, became a visiting professor at the Royal College of Art and was honoured with two major career-spanning retrospectives at London’s V&A (in 1987) and The Design Museum (in 2011). A permanent exhibition of his archive goes on display at the new V&A East Storehouse next year.

Born in London’s East End in 1929, he grew up in a happy if ordinary household, “a good old-fashioned…bacon-and-eggs kind of house”, it was “all brown and cream with daffodils on the wallpaper”, he recalled; the antithesis of the modernist lifestyle he would come to embody. His father, Harry Grange, was a constable for the Metropolitan Police and his mother, Hilda (Long) Grange, was a machinist at a spring factory – an early encounter that years later helped cement his fruitful partnership with Anglepoise, where springs are central to the ingenious balancing mechanism.

As a teenager, Kenneth worked at the spring factory and studied drawing and lettering at the Willesden School of Art and Crafts. After graduating in 1947, he became an apprentice for several architects, including Jack Howe - himself once a collaborator with Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius and an important mentor for young Grange. Work on bus shelters, lamp posts and exhibition stands ultimately led to setting up his own design firm in 1958. The elegant teardrop shaped Venner Parking Meter was an early breakthrough, inauspiciously designed while on his first honeymoon. He was married thrice; lastly in 1984 to Apryl Swift, who survives him.

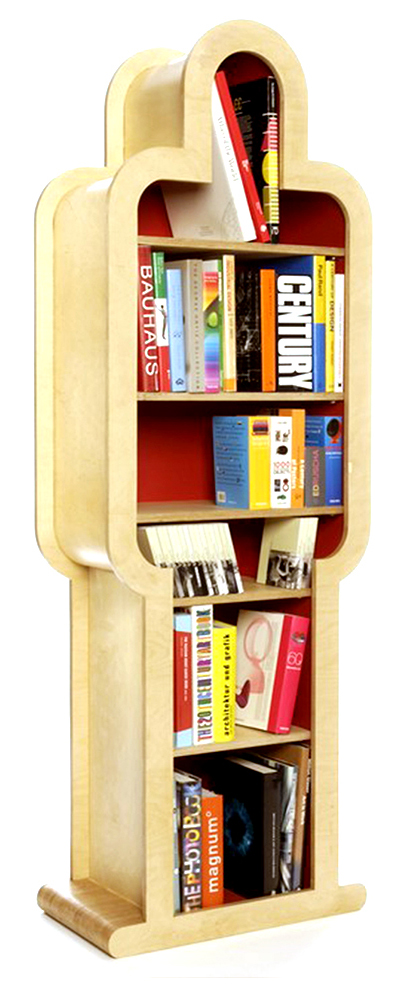

The few years I was fortunate enough to work with Kenneth at Anglepoise were a true honour, as was helping curate his 90th birthday party exhibition at Margaret Howell, back in 2019. In lieu of a convenient table that evening, he worked his way around the room giddily signing autographs for people on their backs, like a 20-something pop star. Many also remember the curiously man-shaped bookcase in the corner of his home in Devon, a bespoke dual-purpose design: “If I ever pop my clogs, it’s booked out and me in, with the lid fixed, up to the great client in the sky”. Another memorable quip came when his lifetime of achievement was honoured with a knighthood. Bestowed at Buckingham Palace by the Prince of Wales, he managed to break the ice with the Prince by remarking on the importance of not wobbling on one knee, “in case I lost my head to the sword”. Practicality and humour hand-in-hand, as ever with Kenneth.

Farewell then to a titan of the British design industry, but moreover an immensely likeable man and a life well-lived. We can all only hope to be half as sprightly and creative as he was in his 10th decade. And retirement? Not if we’re lucky.

by Chahna Tank Oct 15, 2025

Dutch ecological artist-designer and founder of Woven Studio speaks to STIR about the perceived impact of his work in an age of environmental crises and climate change.

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 14, 2025

In his solo show, the American artist and designer showcases handcrafted furniture, lighting and products made from salvaged leather, beeswax and sheepskin.

by Aarthi Mohan Oct 13, 2025

The edition—spotlighting the theme Past. Present. Possible.—hopes to turn the city into a living canvas for collaboration, discovery and reflection.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 11, 2025

The Italian design studio shares insights into their hybrid gallery-workshop, their fascination with fibreglass and the ritualistic forms of their objects.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Oli Marshall | Published on : Aug 08, 2024

What do you think?