Aashti Miller's intertwined career as an architect by day and illustrator by night

by Rahul KumarSep 14, 2022

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Maanav JalanPublished on : Oct 16, 2024

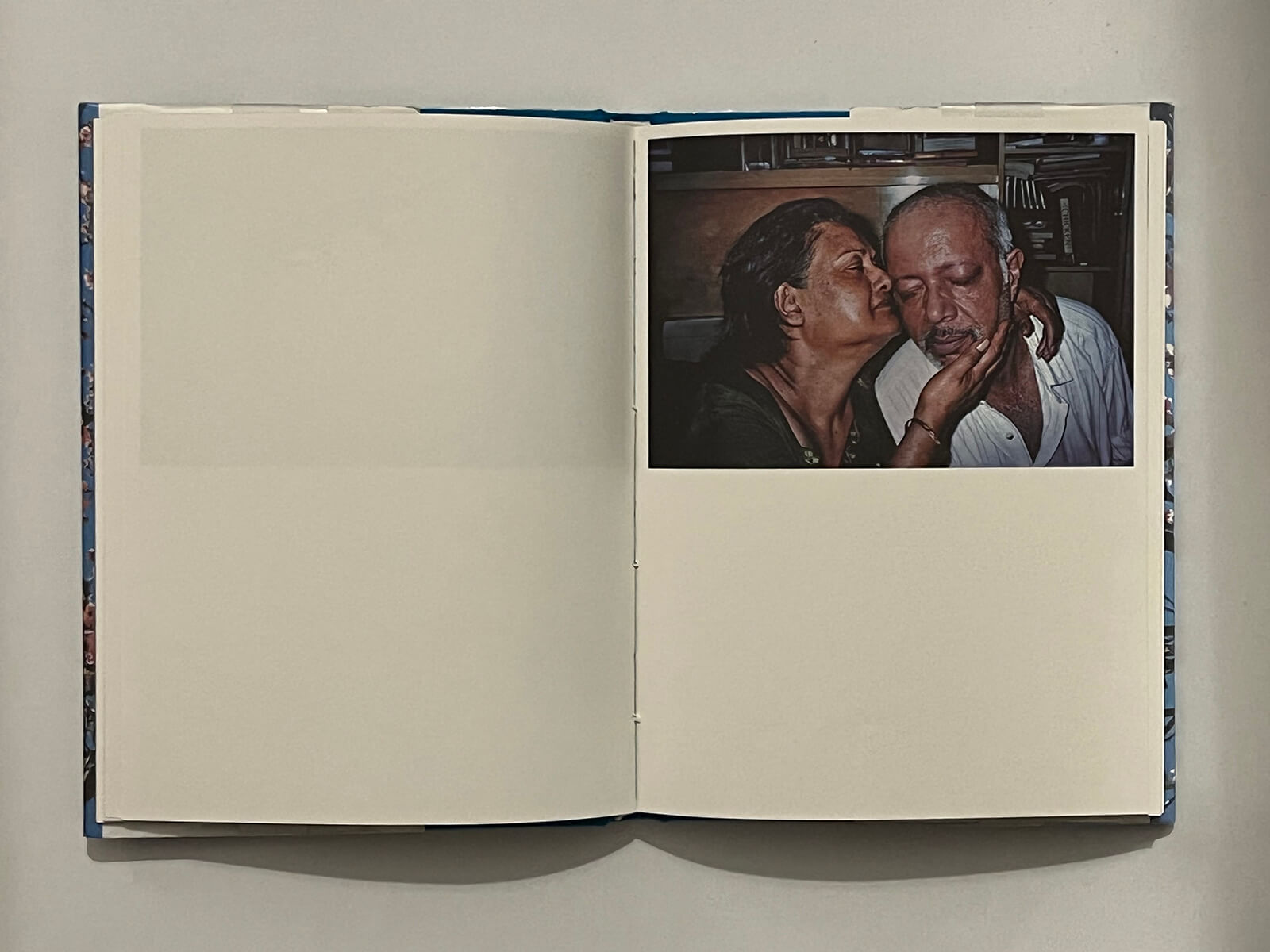

Sohrab Hura doesn’t simply say he is interested in stories, or gardens, or that he cares about his readers. He says he wants to be with plants, he wants to care about how his reader holds his books; he is interested in if he wants to tell a story in a certain way. In all of the New Delhi-based artist and photographer’s work, there is his hand, constantly reflecting, editing and recalibrating its mark. He uses metaphors to describe these processes — editing is like 'picking at a scab', reproducing images is like ‘grafting cuttings’, and storytelling is like puppeteering. These scenes — crystalline, delicate, and bodily — form the conceptual arteries of his work.

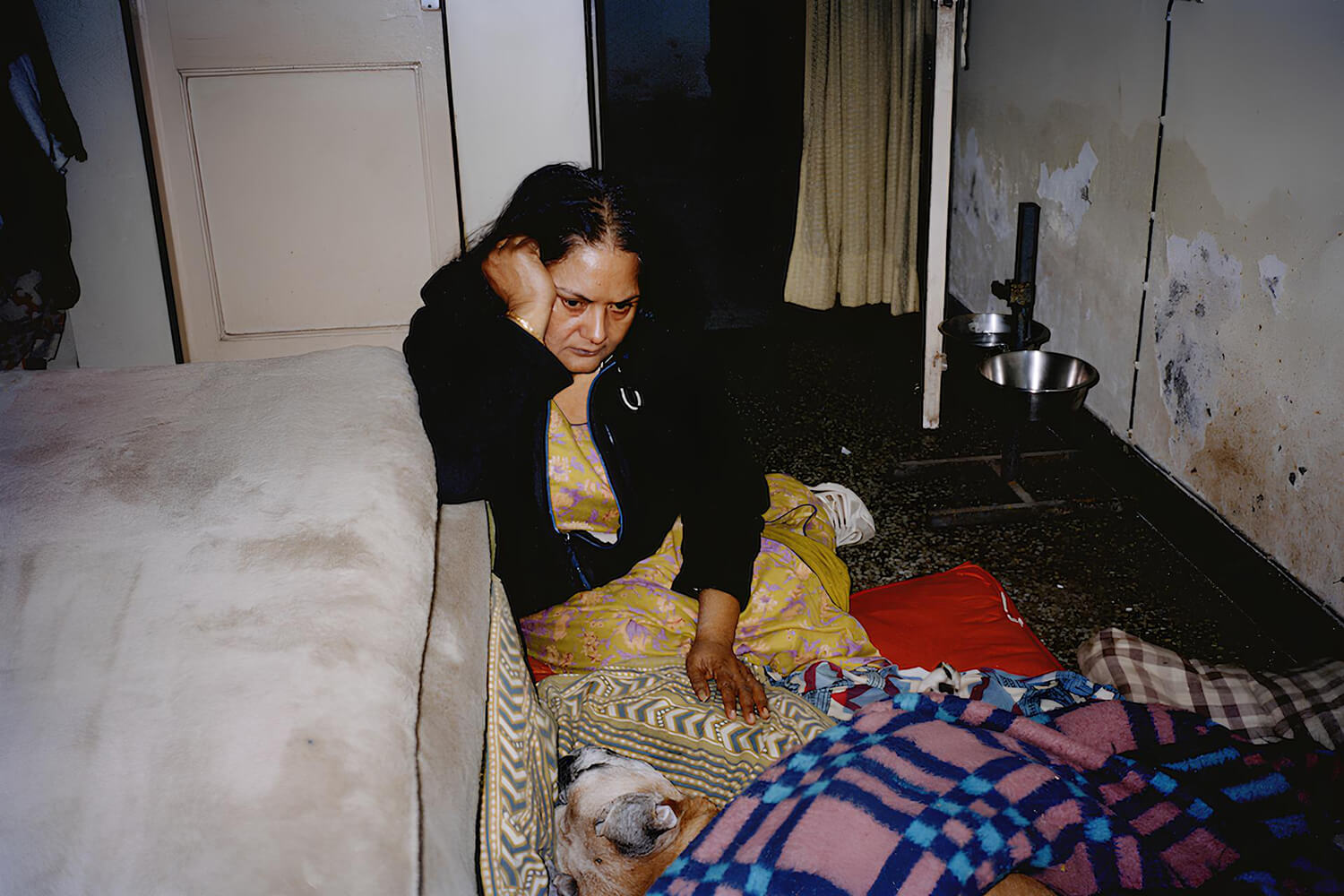

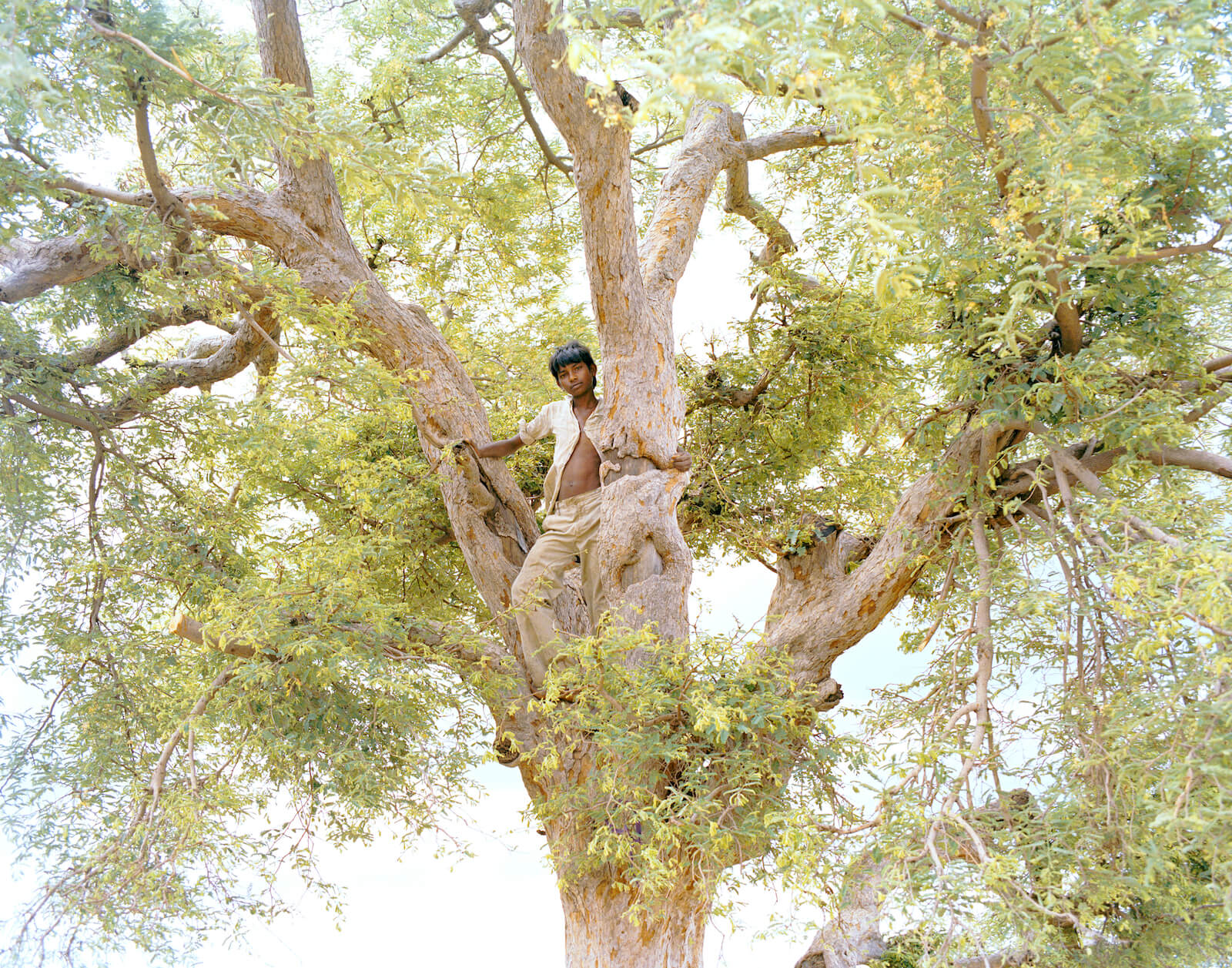

After a master’s degree at the Delhi School of Economics, Hura turned to photography with the hope that it would be a more powerful humanistic tool than economics. One of his earliest photographic projects is from his experiences participating in the Rozgar Adhikar Yatra in 2005, a 4000-kilometre march across India undertaken to demand the right to work, where he discovered Pati, a cluster of villages in Central India, which became a constant subject and site of return. Since then, he has loved and been frustrated by photography; made photographs of family and those involving fictional characters such as a headless woman and an idiot photographer; taken up other more ‘vulnerable’ mediums such as pastels and gouache — all to figure out new ways of addressing us and the work itself.

In the two weeks leading up to Mother, his survey show at MoMA PS1 in Queens, New York, we corresponded over email to talk about the exhibition, where he will show works from across his career — including the early Pati, which he says still guides the way he looks, to his most recent work Timelines, a series of painted cardboard boxes, like ones in which he would ship self-published books, which can be folded and unfolded to make different narrative combinations. “The timelines run across people, places, events and even little things like bees,” he says.

Excerpts from a conversation with STIR below:

Maanav Jalan: Maybe we can start with the notion of a survey exhibition. In your note on your exhibition at Huis Marseille in 2021, you prefer to see the exhibition not as a retrospective but as ‘spillage’, something like ‘drops of water splashing out of a bucket’. I am curious about how you are imagining Mother. Is ‘survey’ a useful way to think about it?

Sohrab Hura: Ruba Katrib, Chief Curator at MoMA PS1, had not reached out with the idea of a survey show. The prompt that I got from her over a year ago was just the space — the five rooms of the gallery and how I might imagine them. The space filled up quite organically as I started playing with the layout. I had no intention of a survey show or even anything thematic. I was just trying to see if I could figure a way out to generate forces of push and pull within each room and across the rooms. It’s a bit like book-making for me, in which ‘play’ is really important. If I were to think too consciously of a theme before starting to put the book together, then it might end up becoming more like a catalogue of those ideas rather than the idea itself.

The process of putting everything together continues from past experiences of installing other exhibitions and that in itself had been built upon how I make my work in general — playing with mediums, meandering, a bit like being in a room at night with the lights switched off and feeling my way about in the dark, then switching the light on to clarify and consciously collate my ideas and then switching the lights off to be able to meander loosely again, and so on.

In the end, we called it a survey show more for practical reasons, I suppose. It literally has works from different periods of my life. But I hope that if people were to experience the exhibition, they would see ‘the many lives of images’ rather than simply a survey exhibition where I am the anchor point.

I’m always interested in looking at photography as a range rather than a category. – Sohrab Hura

Maanav: Is there any kind of story or metaphor you are working with for this show? Is the title, Mother, a conceptual anchor?

Sohrab: Ruba had noticed that many of the smaller works within the show were titled Mother or had the word ‘mother’ within a larger title, and that’s how we arrived at the word. I like that it was as simple as that. It is now interesting for me to look at some works that I may not have imagined coming together under such a title. Maybe the title becomes the spillage here rather than the anchor.

Maanav: What about the image of the tree and its network of branches as the blueprint of an exhibition, as you described for Growing Like A Tree that you curated with Sabih Ahmed of Ishara Art Foundation in Dubai?

Sohrab: I remember at some point writing about a fixed tree that was shown to me as a young artist, that might have been metallic and shiny and supposedly beautiful in its shine. I realised that mine was a completely different tree, that what I thought was a tree was a forest that had, in fact, been a tree at some point. I was talking about canons and histories, about the system that I was told that I had to accept. The shiny metallic tree was too fixed and un-alive.

I’m quite happy to allow a new work to emerge out of a part of a pre-existing work. It’s like gardening. – Sohrab Hura

Maanav: Your works often exist in many forms, and images or text in one project or page are often also used in another. I am curious about your relationship with storytelling. What is the value of making and breaking stories to you?

Sohrab: Storytelling is a lot more than telling stories [and listening to a story is] a bit like watching a puppet show. The story is being narrated and your eyes are fixed on the puppets but there is a lot more at work behind the curtains. What I’m trying to say is that for me everything is a story. I’m interested in whether I want to squeeze out a hidden part of it briefly or cloak up the most obvious parts of it, to tune away distractions.

Earlier on, I’d always struggle to define what kind of a storyteller I was because, unlike in literature, in photography, we haven’t quite arrived at that easy way of distinguishing between forms. I’m always interested in looking at photography as a range rather than a category. At one endpoint of the range, there is complete transparency in the story. Every little detail is known. At the other endpoint of the range, no information is accessible. Any kind of storyteller, a journalist or a poet, has to find their sweet spot on this range, which is also relational to the world around it. So one story being told by one specific storyteller in one place among one set of people at one time might change meaning completely if any of those factors are changed.

So what is a story? I don’t have a clear answer and I am not looking for [one], because it’s all very fluid. I’m interested in working along that paradoxical range and in response to changing situations. And sometimes stories change too. Meanings are constantly fixed and I think it’s important to loosen them up a bit, or sometimes, vice versa. I guess how I might retell the story, or shift a little bit on that range line, might have something to do with how I want to loosen or fix the story.

Maanav: And in each retelling, the specific material you use remains a bit similar and a bit different.

Sohrab: I’m quite happy to allow a new work to emerge out of a part of a pre-existing work. It’s like gardening. You tend to the plants, sometimes you take cuttings, sometimes you can graft a cutting onto another plant and so on. Some gardens are a bit wild. When I leave my apartment here in Delhi and walk down the lane, the most common sight is neat lines of potted plants at equal distances along walls, meant to create a sense of geometry and harmony. While I appreciate people’s love for plants, this is not my kind of garden. I like my garden more like a grove with an opening that one can enter. Where leaves of one plant disappear in between the leaves of another. The idea is really to work with how I want to be with the plants and not how I want to see the plants. My work is also like my garden.

Maanav: How do you look at some of your earlier works like Pati now?

Sohrab: I’m glad I made a work like Pati. I only wish I had done more work back then. But I was having an existential crisis with the medium back in 2005-06, that lasted many years. I was coming to terms with the notion of having power as a photographer and wasn’t able to make any more photographs. But now, I wish that I had continued to work because there isn’t much of a visual archive of the Right To Food movement and the beginnings of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act [NREGA; the context and subject of Pati], for example. With all the re-naming and re-writing and revisioning of history going on, I wish I had made a larger archive.

Maanav: I want to mention the very funny pencil wall text you use to mark your works. Why use handwriting?

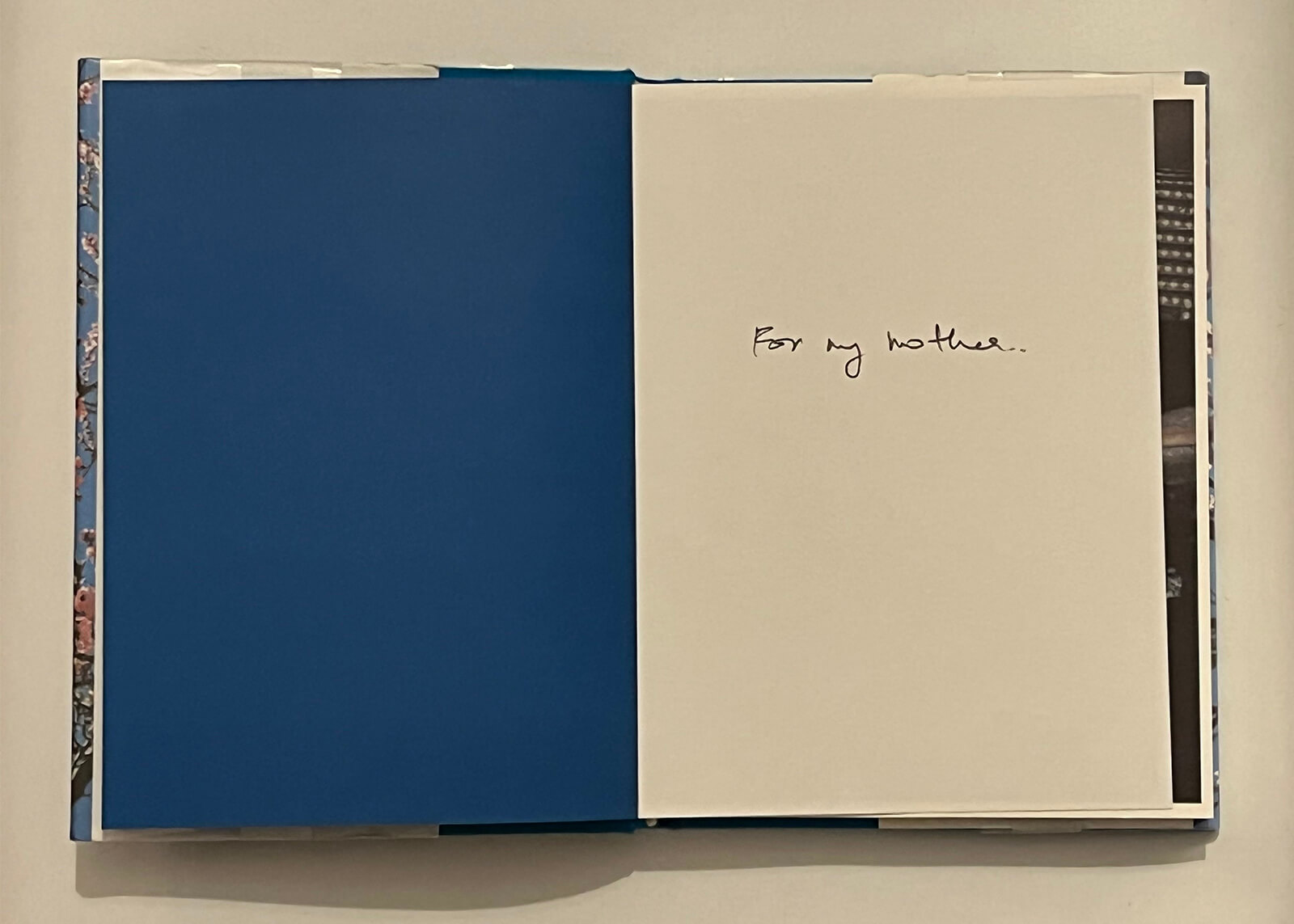

Sohrab: I have been writing by hand for the last 40 years now, I guess. Even when I published my first book, Life is Elsewhere, I decided to use my handwriting both because I wanted its brokenness and because I was a bit scared of getting the font choice wrong. That first book starts with a letter that I wanted to work as an address to the reader so that they could make the book their own.

But it’s not limited to handwriting. I want to care about how a reader will hold the book in their hand. For example, I just published the book Things Felt But Not Quite Expressed (MACK). Here, besides the handwriting, the book is also foam-padded, so when you hold it, it’s a bit squishy. It’s really to take away any kind of preciousness from the book and make it more gooey. Inside, there are these drawings that are of love and whatever else from everyday life, including news events. In this image-saturated world, a kind of numbness has set in and I wanted the handwriting, the silliness and the haptics of the book to break through the numbness as much as possible.

Maanav: Many of your photobooks begin with dedications. Do you think of your works as being addressed to loved ones?

Sohrab: It’s a bit like cooking for specific people. You might have a recipe for a dish but maybe you want to cook it for someone specific and you cook it for them and the food tastes different than how it might have tasted if you had cooked the dish for yourself or someone else.

These excerpts of a longer conversation highlight Sohrab Hura’s sustained interest in telling stories and storytelling. From early photographs made of the people of Pati, who he says “looked at photographs as a gesture of love in a way I had not done so myself,” to more recent “bad images” made in gouache and pastels in search of a slower medium, each of Hura’s works asks anew the question, “So what is a story?”

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Maanav Jalan | Published on : Oct 16, 2024

What do you think?