Local voices, global reach: Latin American art fairs gain ground

by Mercedes EzquiagaApr 28, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Hili PerlsonPublished on : Feb 03, 2025

Had things gone according to Franz Kafka’s last wish, we would never have gained access to some of his most important manuscripts. Canonical novels such as The Man Who Disappeared (America) (1927), The Trial (1925) and The Castle (1926), along with numerous stories, were unfinished at the time of his death from tuberculosis at almost 41. Thankfully, Kafka’s friend Max Brod defied the writer’s request that all his unfinished manuscripts be burned after his death. In fact, Brod even saved them from sure destruction in 1939, when he took the manuscripts with him on the last train out of Prague before Hitler’s soldiers marched in.

In commemoration of the centennial of Kafka’s death, the Jewish Museum Berlin is presenting dozens of handwritten manuscripts and sketches, some on view for the first time, on loan from Israel’s National Library. Yet, in addition to physical accessibility to notebooks that have languished in bank safes and private storage for decades, the notion of access is also the metaphor around which the exhibition’s curator, Shelley Harten, has organised the show, creating a criss-crossed path of themes in Kafka’s work through artworks by some of the biggest names in contemporary art, as well as through Kafka’s original notebooks, filled with his elegant handwriting and drawings and presented under glass vitrines.

“Kafka is thinking about access all the time: access to the law, to a castle and so on. Access is a theme in Kafka’s texts but it’s also an image he uses often; he writes about doors, windows and entryways a lot,” Harten told STIR. “He was also very interested in the question of what does it mean to have access to one’s art—in his case, to writing,” she added. “He is writing in images, which are created in our minds. Many literary scholars speak of this aspect of Kafka’s work and I thought his language is similar to that of many visual artists today who engage with questions through opening up to complexity.”

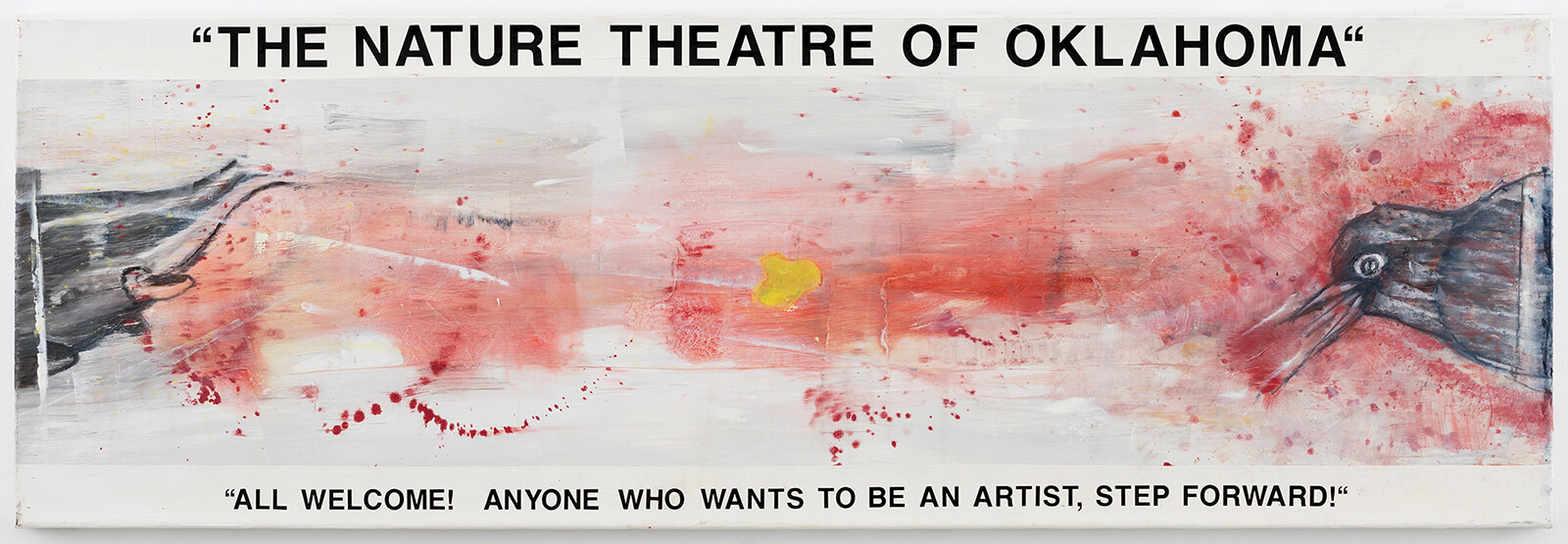

Kafka, who worked in insurance by day and wrote at night, had of course lingered on moments in which access is, rather, denied or complicated through impenetrable and absurd bureaucracy. Honouring the Kafkaesque, the first room in the show is themed “Access Denied”. Hito Steyerl’s video work Strike (2010) shows the artist approaching a flat-screen monitor with a hammer and chisel—traditional sculpting tools—to hit the screen with a single blow, rendering it unusable, but at the same time revealing its colourful matrix. An action painting of sorts. Nearby, an untitled 1991 installation by Martin Kippenberger includes a circular colourful rail and an ejector seat, forever doomed to go in circles. Here, there’s a very direct connection to Kafka, which the curator preferred to otherwise sidestep: Kippenberger used a similar carousel in a related epic installation titled The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika”, which references Kafka’s unfinished novel The Man Who Disappeared (America).

In the gallery themed Body, the exhibition delves into Kafka’s thinking about the performing arts, appearing in several of his works, including the last book he oversaw for publication—A Hunger Artist (1922). In this context, documentation of Tehching Hsieh’s near-masochistic one-year performances certainly packs a punch. Reflecting on the tragic ending of Kafka’s hunger artist, who withered away without recognition for his ultimate sacrifice, Hsieh’s radicality in the name of art is confounding: the year he confined himself to a cage, the year in the early ‘80s when he lived on the streets of New York, or the one year he tied himself to artist Linda Montano with an eight foot piece of rope with the intention not to touch each other. Unlike Kafka’s fictional protagonist, Hsieh has cemented his place of honour in the annals of art history by pushing his body and mind to such extremes. This section also includes the video work AI Winter (2002) by Anne Imhof and numerous paintings by Maria Lassnig, whose portrayals of the ageing body, supported by various objects and crutches, speak of an artist’s capacity to externalise inner states.

The performing arts, or more specifically, Yiddish-language theatre, was also Kafka’s entry point into Judaism. Hailing from a secular, assimilated Jewish family, he didn’t write explicitly about Judaism, but he learned Hebrew (some of the notebooks on view include Hebrew words) and it was in Yiddish theatre that he experienced a sense of Jewish community. Fittingly, the gallery themed around Judaism includes a remarkable new work by Yael Bartana, Mir Zaynen Do! (We Are Here!, 2024), shot at the dilapidated auditorium of the Yiddish theatre in Saō Paulo, Brazil, inaugurated in 1960 by Jewish immigrants. There, a choir led by a tiny yet grandiose elderly woman sings a Yiddish song on stage. An Afro-Brazilian music ensemble that draws on Candomblé enters the theatre and the two songs, in the two languages, are effortlessly overlaid and blend into one another, sonically if not visually.

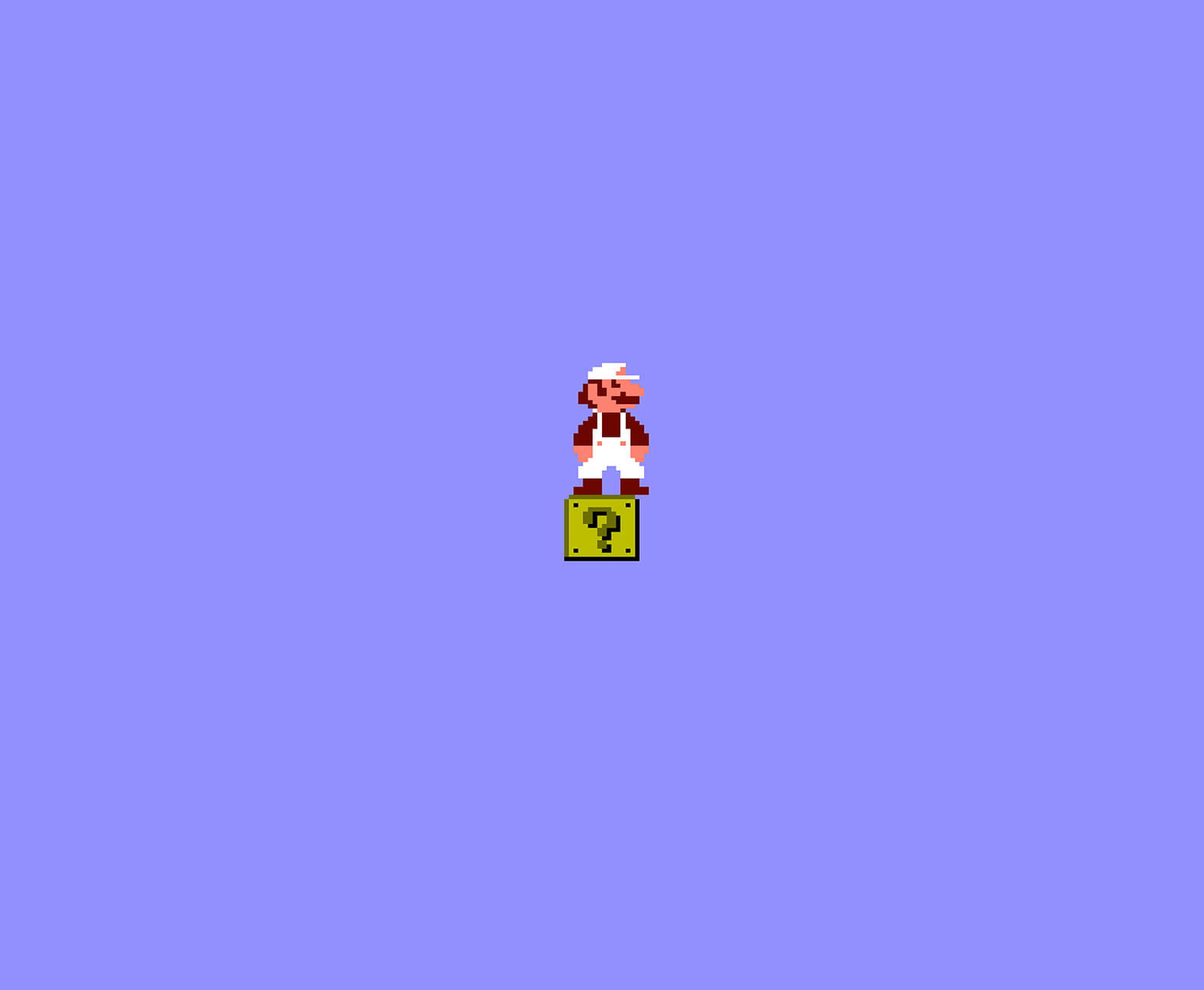

The works in the gallery themed around the notion of space in Kafka’s work, unsurprisingly, bend towards the bleak and darkly humorous. Cory Arcangel’s Totally Fucked (2003) shows the video game character Super Mario stranded on a cube marked with a question mark in a sea of emptiness, with no available next move. On the opposite wall, Guy Ben-Ner’s House Hold (2001) shows the artist engaged in a series of excruciatingly unwise, unproductive and painful actions to free himself from the crib he had gotten trapped under, an ordeal he could in fact very easily get himself out of.

Kafka famously asked that the insect that the ill-fated Gregor Samsa turns into in The Metamorphosis (1915) never be illustrated. (This is but another of Kafka’s blatantly overlooked requests.) The cover of the novel’s first edition—on view here—actually featured a slanted door, ushering readers into the domestic settings in which the novel unfolds. This motif of a seemingly average family house and the toxicity that lurks within it are at the core of artist Gregor Schneider’s work. Schneider has worked on the site-specific, long-term project TOTES HAUS u r since 1985, adding rooms and corridors within the rooms, building layers on top of layers to the structure. To revisit images of Schneider’s madman’s project in reference to spatiality in Kafka’s writing, which renders the familiar oppressive, is unexpectedly thrilling.

'Access Kafka' is on view at the Jewish Museum Berlin until May 4, 2025.

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

by Hili Perlson Sep 26, 2025

The exhibition at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus unpacks the politics of taste and social memory embedded in the architecture of the former East Germany.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 25, 2025

At one of the closing ~multilog(ue) sessions, panellists from diverse disciplines discussed modes of resistance to imposed spatial hierarchies.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Hili Perlson | Published on : Feb 03, 2025

What do you think?