Advocates of change: revisiting creatively charged, STIRring events of 2023

by Jincy IypeDec 31, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Oct 14, 2025

The fable of a slow lifestyle at the precipice of the pandemic felt for most like an antidote to the instantaneity of the digital age—of a culture of hyperconsumption predicated on incessant productivity and instant gratification. The fatigue from an ‘everything everywhere all at once’ mindset has led to a deliberate focus on sustainability in the everyday—translated through an emphasis on local produce, businesses and the desire to live in tune with nature—seemingly as a counter to a world disintegrating on a livestream. To be able to slow down is to remove yourself from a constant state of survival. However, this appeal feels altogether ironic at the height of the unofficial season of architecture biennales, design events and fairs. There seem to be at least five large-scale biennales occurring in tandem elsewhere in the world right now. To this roster, the festival calendar this year adds the Copenhagen Architecture Biennale, organised by the Copenhagen Architecture Forum (CAFx) and curated by CEO and founder of the organisation, Josephine Michau. The Biennale takes that very plea—to pause and consider architectural practices under new planetary rubrics—as its central theme, Slow Down.

CAFx’s decision to move away from their previous format of annual events in some ways indicates their desire to de-escalate as well. This year’s programming for the architecture festival, on view till October 19, 2025, then feels more concentrated than most, with a succinctly curated list of participants. Michau hopes to critique the consequences of the Great Acceleration through acts of design on display during the Biennale. First coined by authors Peter Engelke and John Robert McNeill, the Great Acceleration is the historical period in which we can discern an unprecedented spike in population, energy use and resource consumption, leading to an increase in geological activity (increased CO2 levels, higher temperatures)—evidences of the Anthropocene epoch. By shifting the gaze to the planetary implications of design, the participants are able to acutely consider architectural practise and the construction industry’s impact on earth systems as a whole. Works attempt to offer a holistic purview of how we got to where we are and what resilience might look like in the future.

In this, the Biennale centres architecture practices—largely from Denmark but including other parts of Europe—that posit notions of circular design, regenerative ecologies, narratives of reuse and alternative material innovations. The Slow Down Pavilions and a group exhibition under the same moniker as the architecture event’s conceptual spine bookend the festival programming. Other smaller events, exhibitions, installations and workshops have been planned across Copenhagen and engage quite specifically with the urban conditions of the city, highlighting radical possibilities of intervention within seemingly unresponsive and degraded environments. A number of workshops that hope to engage local communities, for instance, spotlight sustainable practices of food production, permaculture, urban mapping and planning, and in this way raise awareness about local actions that one can partake in to be more conscious of consumption. The Garden of Decay, along similar lines, presents the garden as an archaeological site, allowing visitors to move away from an anthropocentric conception of their urban surroundings.

Other interventions look at the existing built fabric of the city, questioning what practices might give it new life. Examining this question, on the former Frederiksberg Hospital site, an old chapel has been refurbished through a careful process of repair. A similar approach is explored by artist collective Lokale with their project, Pillars. Taking over a former hospital gift shop, over the course of the Biennale, the artists have been constructing three pillars from salvaged materials, resurrecting a form of urban memory marking the site’s transformation into a residential zone. Exploring vernacular material vocabularies, a pavilion by the Royal Danish Academy has been constructed from unfired building tiles. Fashioned from clay gathered from fields around the country, the prototype is a demonstration of the effectiveness of simple, widely accessible materials for construction and the forbearing notion of regeneration. Made from clay, the pavilion will eventually succumb to the forces of nature.

The conceptual underpinnings of the Biennale are most pronounced in the group exhibition, housed in two venues, Halmtorvet 27 in Copenhagen and the Form/design Center in Malmö. With less than 20 participants across the two galleries, the focused scale of the show allows Michau to proffer a multiplicity of perspectives while highlighting her staunch position on the state of architecture today: that we have strayed from the rhythms of nature and only through a return to the natural, to unhurried practices of care and repair can we forge ahead. Divided into four sections, the show argues against the idea of certainty or the adoption of a fixed position from which to think about and practise design. Instead, through immersive installations, prototypes and research proposals, it asks visitors to consider what observation, silence, restraint, humility and hesitancy can show us about the built environments we inhabit. Four thematic turns—the Forensic, Material, Archaic and Political—groups these dispositions under new ways of doing and looking at design.

It is here that the Biennale makes its boldest assertions by yielding to a position that does not prescribe. Instead, it inquires, notices and speculates on what else is possible. For instance, in the Forensic Turn, Tonda Budszus examines the global networks that facilitate the transport of materials for construction with a film that livetracks ship routes. In revealing the often extensive distances materials traverse, Budszus brings to the fore the slow duration of construction processes, while underscoring their fallacies. Even ‘sustainable architecture’ or ‘green buildings’ are not exempt from the carbon costs incurred by the transportation of materials. And even if they are, can they truly offset the scale the industry operates at today? Barring ceaseless, inconsiderate extractivism, how do we rethink what it means to construct and, more importantly, what do we do and how do we live with the present’s burgeoning development in the future?

In Material Turn, the forces that transform our buildings—natural as well as technological—are the protagonists. Pablo Castillo Luna’s A Permeable Atlas, for instance, reveals both the seemingly inconspicuous and reciprocal relationships of buildings with water. Through architectural drawings and mapping diagrams, Luna explores how infrastructure seeks to control water, but must ultimately submit to leaks, bursts, faults—to the inevitable sovereignty of the natural. In recent years, architects and academics alike have advocated for a more-than-human stance on the practise of architecture, to stage porous approaches toward the non-human actants that actively and mutually transfigure our environments. In the Archaic Turn, this is highlighted through the vitality of indigenous practices that think of nature and humanity as intertwined and look at modalities of being other than the ones dictated by modernist notions of time.

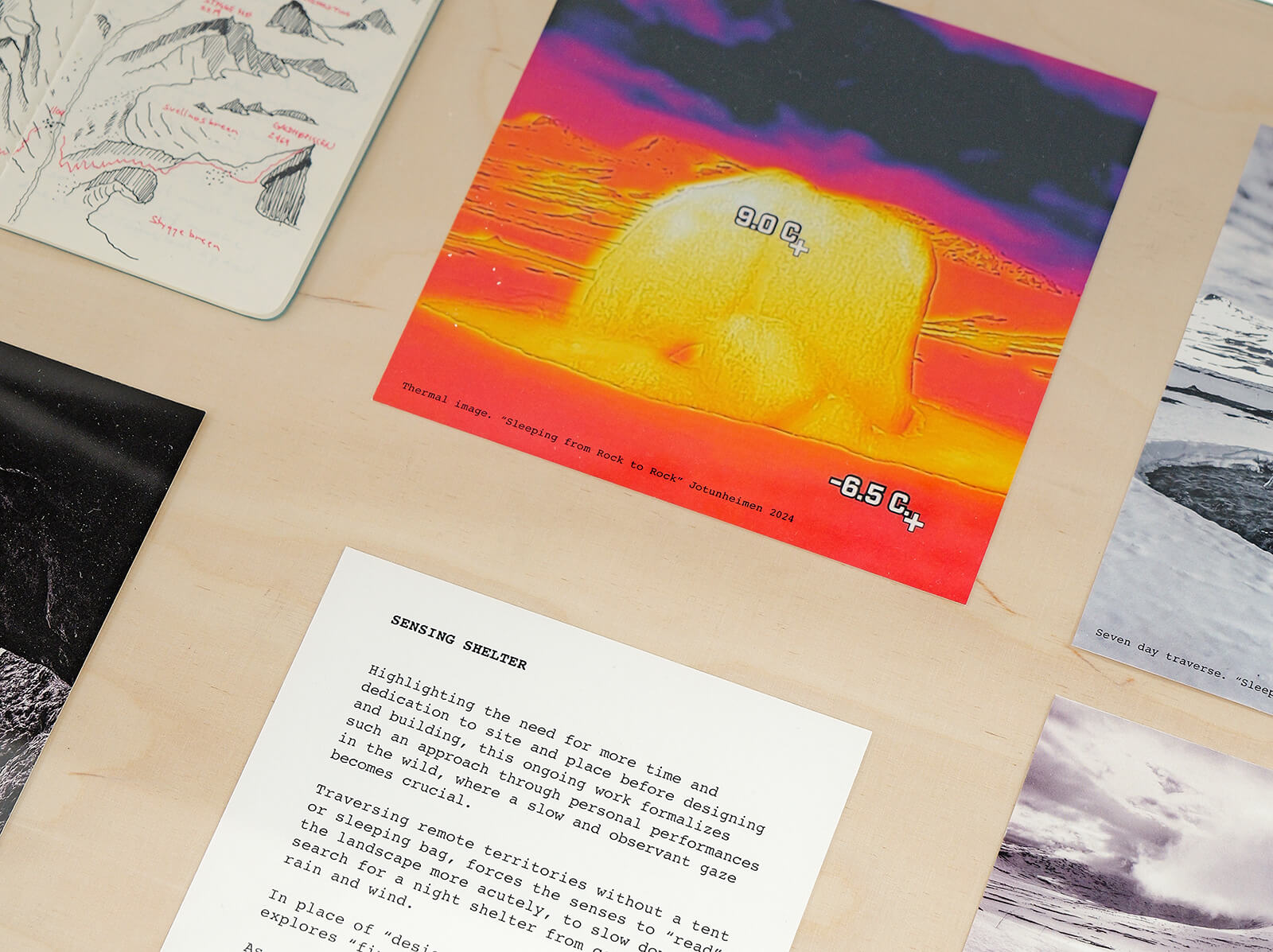

For his project Sensing Shelter, Danish architect David Garcia imagines an approach to ‘sheltering’ where he personally spends time on a potential building site to “sense” the landscape more acutely; an active dialogue instead of a passive register. Conversely, Polish architecture practice Centrala's Celestial Architecture hopes to return humanity to cosmic rhythms of being. Their original project, located in Warsaw, was composed of 10 architectural, topographical and garden installations, strategically placed to be able to experience the diversity and subtlety of celestial phenomena. In the same vein, Danish artist EB Itso’s interactive installation, The Blue Room, is presented as a hypothetical spa. Through videos depicting natural landscapes, Itso advocates for a culture of slowness, built on the models presented by nature. In this, it recalls the same desire to return to premodern modes of being. All the exhibits then purport this one central question, what future pasts are possible?

The Slow Pavilions—the other main prong of the showcase—are conceived as a material exploration of this central concern. Meant to act as an ‘experimental laboratory’, the two designers chosen by the curatorial team to realise their projects on site attempt to rethink construction processes through an intentional slowness. Their positions similarly act as prompts for visitors to slow down, to rest awhile. For their pavilion, Slaatto Morsbøl emphasise circular design practices by reusing discarded materials. Located at Søren Kierkegaards Plads, the structure is constructed from materials salvaged from various demolition sites in the city, with each of the materials used being cut in half to expose its core, enabling a more intimate understanding of the ‘stuff’ that surrounds us. By not insulating or covering any of the building materials, the designers incite an architecture that the environment can actively alter, bit by bit, second by second. The other pavilion design, Barn Again by Tom Svilans & THISS Studio, similarly makes use of reclaimed timber elements for its structure and facade. It interprets slowness not only programmatically (a space of respite in the middle of the city), but through its building methods (with its traditional architectural language contrasted with new joinery and precise machine incisions) and by prolonging the material value chain of what is deemed as waste (through the act of recycling).

With a focus on the slow and the deliberate, the inaugural edition of the Biennale makes a valiant attempt at decentralising narratives of capitalism wherein the ultimate goal seems to be the pursuit of ceaseless progress. Instead, it argues that a future imaginary must lie with the planet as a heuristic category, where the personal, the biological, the political and the geological intersect. What the Biennale inadvertently overlooks, however, is the simple fact that, for most of the world, architecture and design are already relatively slow processes, requiring not only years of manual labour, but also years of planning and approval processes. The insistence on looking away from the industrial to the handmade, to local and vernacular practices, is then a u-turn that the Global South must reckon with after years of trying to ‘catch up’ to the lofty ideals of Western progressivism. For the formerly colonised, the onus of de-escalation is not simply imperative—it is an imposition; the continuation of a colonial legacy in many ways.

The Biennale’s merit then, lies not in the idea that limitation—of material extraction, construction, development for development’s sake—is necessary, but in proposing an entire overhaul of what we conceive of as design or architecture. It is by pausing, by relooking, rethinking and reimagining that we can begin to preserve the little we have not destroyed, and possibly, in the future, regenerate what we have. So, if one has the luxury—not having to immediately worry about intensifying natural disasters or ecological collapse, or the steady erosion of our land’s precious resources—the exhibition opens out time to reveal a more glacial, cautious mode of being. But with fair warning—if we don’t hurry up, it might already be too late.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Oct 14, 2025

What do you think?