Cindy Sherman’s ‘Anti-Fashion’ gains new meaning amidst Antwerp’s Ensor Year

by Hili PerlsonNov 15, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Marcus CivinPublished on : May 11, 2024

I drove seven hours from Brooklyn to see the Stanley Whitney retrospective How High the Moon at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum. I could tell I wasn’t the only one who made a pilgrimage. When the guards returned to the galleries after their lunch breaks, they didn’t seem surprised to see many of us still lingering there. Although arguably one of the preeminent abstract painters in New York, Whitney is consistently humble. Given a microphone, he will emphasise his rafts of artistic influences and how it took him decades to land on his signature style—three or four rows of deceptively simple, colourful, even luminous blocks. This show has been a long time coming, and it’s clear Whitney’s journey has been a momentous one, even though the art world underestimated him until recently.

Looking back, Whitney got the message that almost everyone expected he should be something else—a realist painter maybe, or more explicitly political, or not an artist at all. Certainly, a Black abstract painter didn’t fit well in narrowly constructed narratives. While studying at Columbus College of Art and Design, then Kansas City Art Institute, Whitney put time in on garbage trucks and painted houses, while also taking a summer course with the famed painters David Reed and Philip Guston. After school, he worked at the Strand Bookstore and Pearl Paint in New York before Reed recruited him for the MFA at Yale University in 1970. After that, he commuted from New York to Philadelphia for three decades to teach at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University and travelled widely. Seeing the ancient architecture of Italy and Egypt first-hand inspired him to make his paintings more solid.

Color Bar, a six-by-seven-foot oil painting from 1997, seems to be about covering up, possibly an appeal for moving beyond surface impressions. Under red is orange. Under brown is yellow. Under black is blue. Secret of Black Song and Laugher (2003), at three feet square, is brighter, pulsating yellow lights at dawn. Like these two, most of Whitney’s works from the last 25 years or so consist of the irregular grids and variegated rectangles for which he has gradually become well-known. Pick any of Whitney’s works individually, and particular associations may come to mind. For example, a characteristic and charismatic Untitled gouache from 2022 displayed in one of three breath-taking salon-style installations of the artist’s more modestly sized works in Buffalo resembles flowing choir robes if one stares long enough.

Before he found the grid, Whitney’s distinctive shapes, colours, and gestural marks seemed to float more, the works on the whole like mappings of jittery planets. Some of his striking paintings and drawings from his intermediate period of the early 1990s suggest bookshelves filled with heads and ceramic vessels, each charged with lightning-strike brushwork that makes them seem to vibrate.

An avid draughtsman, Whitney’s rigorous drawing practice contributes to his ability to create often effortless-looking paintings. When he works in his sketchbooks, he sometimes thinks about a song lyric or something he’s read. He’ll write these down, perhaps in graphite above or below a grid containing squiggles, watercolour daubs, coloured pencil wisps, or crayon spurts. Although he says in interviews that he didn’t initially intend for his sketchbooks to be public, for the retrospective, many are laid out in cases, open to selected pages. They add additional layers of meaning to his abstractions. In one such book from 2017—reproduced in full and available for scrolling on an iPad at the AKG—Whitney professes his love for bluesmen Muddy Waters and Bo Diddley and also for the writer James Baldwin, quoting from the author, “It’s very important for white Americans to believe their version of the Black experience.”

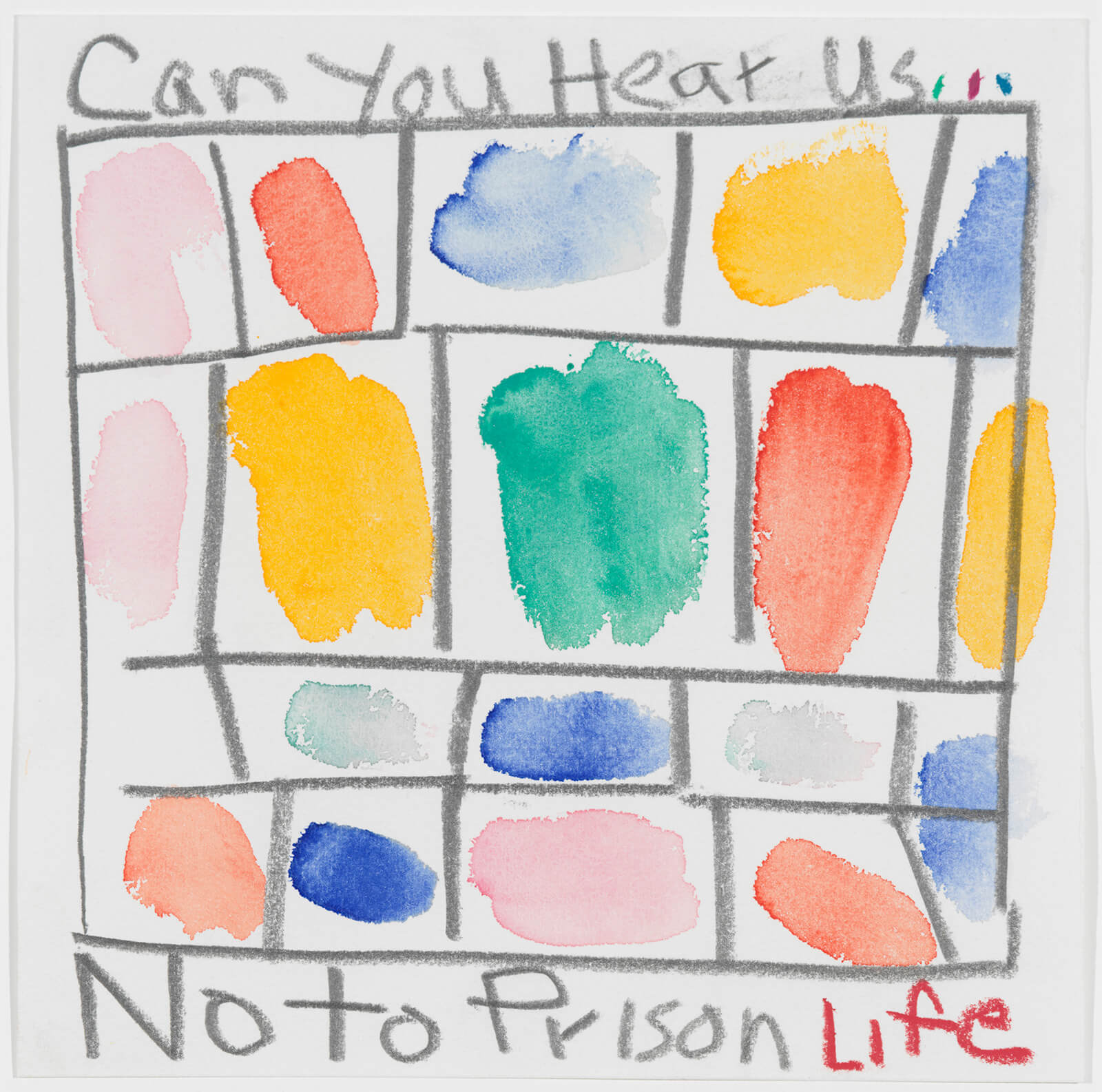

In the late ‘90s, notes about the racist and classist carceral state began to appear in Whitney’s work. His usual grids, unchanged but thus inscribed, look then like jail cells. When the Black Lives Matter protests shook the world, Whitney started sharing drawings like this that repeat, almost as a refrain, the words “No To Prison Life.” In a 2020 interview with his son, the writer William Whitney, he noted, “It’s really very important that we get rid of prisons and think of a better way of healing and educating people.”

Given his general insistence on freedom, it might seem a contradiction that Whitney keeps so religiously steadfast to his now trademark style. He’s decidedly more faithful to a plan than most other painters. The structure might return him to familiar territory, but the result is never exactly the same. The process never becomes mannered or stale and what develops doesn’t feel restricted. By design, even slight changes of colour or form become intensified and lyrical, foregrounding de-regulation and humanity and promoting attention. In a series of works, the repetition of a block or a bar of colour is nothing less than visually explosive. Whitney exercises and complicates hard-earned form—not an end in itself, but a gentle and generous mechanism encouraging us to stop for a breath or two and maybe let ourselves be startled.

Likely alluding to his determination and indelible impact as an artist and the pull of his paintings, Whitney’s friend, the poet Norma Cole, wrote in 2018,

There will be

time

then

there will be

song

for the paintings

say

stay.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Marcus Civin | Published on : May 11, 2024

What do you think?