Ukrainian Modernism charts a nation’s fractured architectural history

by Dhwani ShanghviAug 21, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Bansari PaghdarPublished on : Jul 17, 2025

“Collaboration is the secret life of architecture,” suggests Beatriz Colomina in a 2018 article1 addressing the blatant yet normalised blindness towards women designers in ‘official’ canons. She opines that the nature of architecture is inherently collaborative, requiring collective authorship. In the absence of such an acknowledgement, women still remain the “ghosts of modern architecture”, as Colomina underlines in her essay. "Perceptual shifts amass", she notes. A growing scholarship is beginning to look at the role played by collaborators (such as Lily Reich), partners and even clients (such as in Nora Wendl’s Almost Nothing) in the cultural project of architecture. Joining this necessary crusade, Women Architects at Work: Making American Modernism, published by Princeton University Press, tells the stories of the women who were part of the Cambridge School (1915–1942), foregrounding collaboration in architecture—and in the creative disciplines at large—as an underpinning theme and an essential tool of hegemonic resistance.

Drawing from two decades of research, compiling archives, letters and documents, the book by architectural historian Mary Anne Hunting and academic Kevin D. Murphy presents invigorating, inspiring and, at times, vexing tales of women who refused to remain ghosts. The authors and contributors unearth the intertwined lives of the alumni of the Cambridge School, established as an informal institution in 1915 – 16, serving as the first architecture school to offer women master’s degrees in the United States. It was also the first school in the world to unite architecture and landscape architecture under a single faculty. Informed by “the social order of the time”, Harvard had a strict policy on admitting only male students, as observed by historian Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz. This exclusion led to the founding of the school, which later became affiliated with the Smith College in 1934 to award the students with bachelor’s and master’s degrees. The school was responsible for steering the career trajectories of several women over the decades, who, as the authors posit, were intrinsically involved in establishing the canon of American modernism in the 20th century.

While some women (including Eleanor Raymond, Gertrude Elizabeth Sawyer and Marie Frommer) set up individual practices, many sought spousal (John and Sarah Pillsbury Harkness) and professional (Julia Morgan and Ira Wilson Hoover) partnerships, while others made careers in research/teaching, architectural writing (Ethel Power) and independent design ventures (including Anne Tyng and Porges Hoskin). The authors highlight the spirit of camaraderie and mutual support that permeated the relationships of these women. They thrived on uplifting each other as a means of surviving in an otherwise hostile professional and academic environment.

The school's founding in Cambridge was precipitated when Harvard denied admission to Radcliffe graduate Katherine “Kitty” Glover Brooks in its landscape architecture programme in late 1915. The then department chairman, James Sturgis Pray, advised her to be home-schooled by Harvard’s young architecture instructor, Henry Frost. This led to Frost and Harvard landscape architecture instructor Bremmer Whidden Pond beginning to tutor a small group of enthusiastic women—including MIT architecture students Florence Luscomb and Abby Winch “Winnie” Christensen—in their shared office in Cambridge, leading to a programme of study that was inclusive and cooperative in its very inception. Despite never being associated with Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), the Cambridge School was influenced by Harvard’s faculty and curricula. At the same time, its constantly evolving, inclusive pedagogy gave it a unique identity. The experimental structure of the Cambridge School was a direct reflection of its contemporary nature, especially at a time when breaking from traditional discourse was considered essential to make way for the evolving sociocultural needs of the society at the time.

Central to the school’s vision was equipping women—whose efforts and skilful labour were seen as fit only for the domestic sphere—with definitive professional abilities to establish themselves in the discipline of architecture. Still, the architecture school further catered to the students’ ‘radical’ interests, organising studies around current affairs and encouraging innovative ideas on relevant architectural practices of the time. Since the instructors balanced their time between both Cambridge School and Harvard’s GSD, the students were often left to study by themselves. This, and the fact that students of architecture and landscape architecture studied under a single faculty, led to a highly collaborative learning environment as opposed to GSD’s competitive one. Amidst the systemic sexism, racism and classism, the students of Cambridge School prevailed as professionals by virtue of their comprehensive training and their collaborative and sensitive approach to architecture. Despite its unique, experimental programme, the school shut its doors in 1943 when Harvard began accepting female students, after losing a majority of its male population to mandatory drafting in the Second World War.

As the authors point out through various instances in the book, the graduates of the Cambridge School absorbed this collaborative approach from their academic experience into their personal and professional values, often helping their peers and juniors enter competitive and otherwise exclusionary professional architectural networks. For the authors, Eleanor Raymond and Ethel Power are the centre of the text’s enquiries, as they established several academic, professional and personal ties that many other women in the field benefited from. Raymond was one of the very few women who created her own archive before she passed away, at a time when it was quite rare for women to document their work and for it to be preserved. As editor of the House Beautiful magazine, Power played a major role in publishing the work of many women architects, including her partner Raymond, adding their names to the history of the evolution of the modernist architecture landscape in the United States.

Since men were duly afforded recognition and coveted professional titles and statuses, it was normal for them to secure wealthy clients for their designs, while women struggled to find even the most menial drafting jobs, being deemed unfit for a gruelling profession, reiterated in several sections across the book. Even if they did, they were seldom afforded opportunities to climb the ranks. On the other hand, the women who established independent practices were most commonly approached for interior and residential design projects, struggling to break out of their gender-informed portfolio. Several women architects undertook studies and internships in Europe to expand their knowledge. However, instead of importing the tenets of European modernism, some of them cultivated a distinct language of American architecture informed by regionalism. This position contrasted with that of their male contemporaries, who largely adapted the paradigms of the International Style with quite singular interpretations. As the authors note in the book, women architects preferred designing quiet, regional buildings that complemented the needs of the users and the existing built and natural landscape.

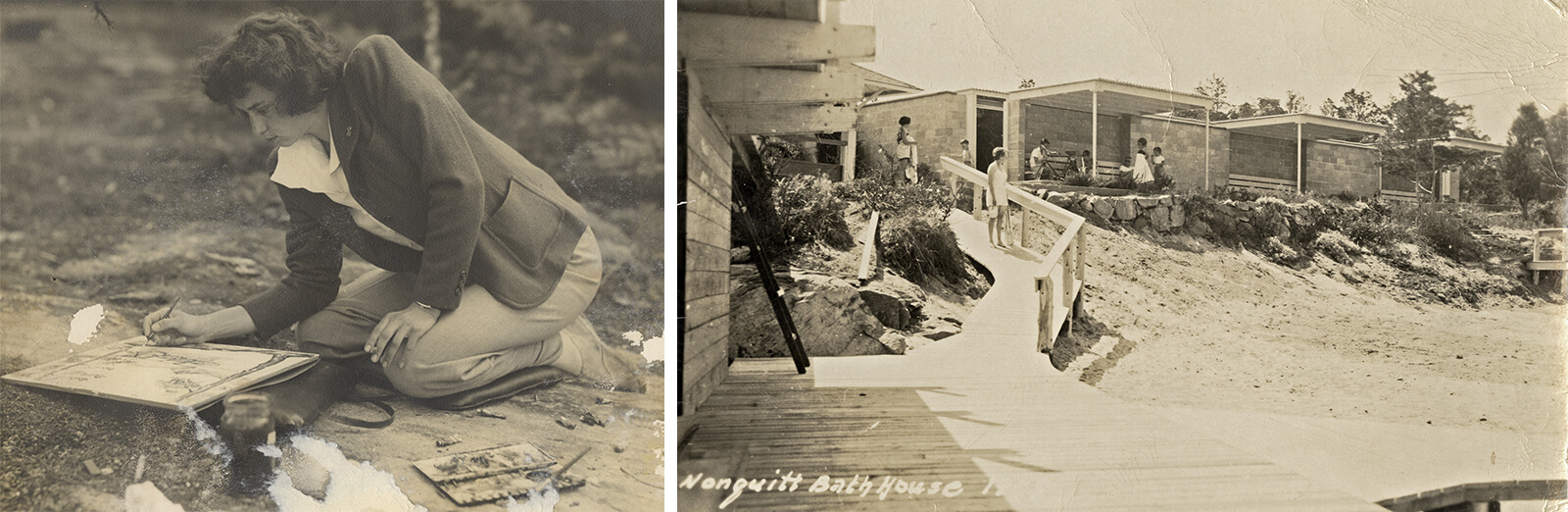

Through the women of the Cambridge School, Women Architects at Work highlights the largely overlooked chapters of American modernism defined by a resistant architecture emerging from collaboration and regionalism. The book meticulously demonstrates how encounters and exchanges with fellow Cambridge School alumni and other professionals profoundly shaped their professional and personal trajectories. As one reads the book, this complex web of narratives—presented alongside letter excerpts and rare photographs of the women in action—unfolds hidden layers of American modernism, often intersecting with canonical narratives that have long championed stories of the ‘individual’ while eclipsing the ‘many’. Its selective histories overlook powerful acts of collaboration, craftsmanship and contextual responsiveness, along with the people, often women, who practice them, undermining their contributions simply because some of these works were not as prominent or conspicuous. The book brings these forgotten, often buried histories to light, asserting them on the timeline of American modernism to forward a cohesive narrative shift. It is a movement that supersedes solo architectural crusades that privilege the ‘hero’ figure of the architect, but also one where distinct pedagogies, contexts and people – all assume stakeholdership in collectively transforming the architectural landscape.

References

1.Outrage: blindness to women turns out to be blindness to architecture itself by Beatriz Colomina, published 8 March 2018 in The Architectural Review

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 16, 2025

For its sophomore year, the awards announced winners across 28 categories that forward a contextually and culturally diverse architectural ecosystem.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Bansari Paghdar | Published on : Jul 17, 2025

What do you think?