Dr. Beski Science Foundation is a community refuge in a remote town in Iran

by Akash SinghJan 02, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Afra SafaPublished on : Nov 16, 2021

This October marked the 50th anniversary of the inauguration of Tehran’s Āzādi Tower, a monument that has been the symbol of both monarchy and revolution, and a space to express the desire for freedom and individual rights through half a century. Today, beside Āzādi, Tehran also has the Milad Tower, an effort in some beliefs to build a monument that surpasses Āzādi in the era of the Islamic Republic. But by which monument is the city best known? And which structure has been more embraced by the different generations of the Iranian society?

In the late 1960s the Shah of Iran had the opportunity to realise a fragment of his dreams. With the increase in the oil prices and economic growth the wheel of infrastructure and civil projects were turning with a fast to bring Iran up to speed. The face of Tehran was changing dramatically and western lifestyle was prevalent among the middle-class capital dwellers. Yet simultaneous to striving to build a modern country the imperial state emphasised on the importance of national and historical identity. Thus, the festivities officially known as the 2500th Year of the Foundation of the Imperial State of Iran were to be held in 1971. These celebrations were organised in two parts; one that was to be held at the location of Persepolis near Shiraz with the attendance of the world leaders, and the other that was meant to be held in the capital. For this to happen first and foremost, Tehran needed a monument to symbolise a country entering a new era of modernisation. The Āzādi Tower is a memoir of that time.

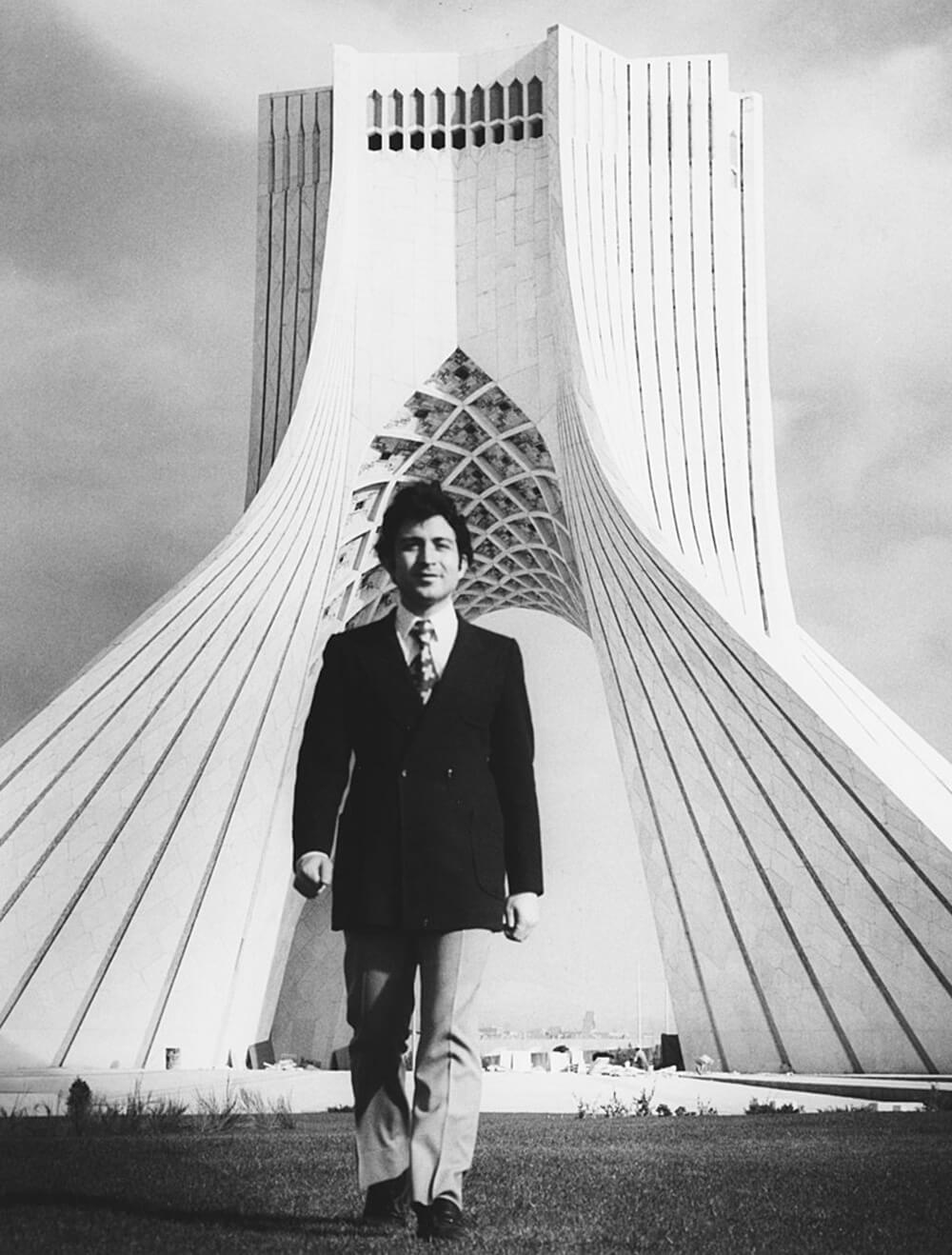

Designed by architect Hossein Amanat, when he was no older than 24, the project was selected in a free architectural competition to design a monument for Tehran. As a young architect Amanat was inspired by all the periods of Iranian architecture and had studied all its noteworthy elements. He was also perceptively aware of how Iranians identify themselves with all the epochs of their history and makes good use of that knowledge.

The long lines extended from the tower’s foot to the top are inspired by the Achaemenid designs of Persepolis, the inner round arch is a reference to the Taq Kasra of the pre-Islam architecture of Sasanians in Ctesiphon and the broken arch above is enthused by the Islamic architecture.

Amanat is also conscious of the importance of mathematics and serial geometry in the Iranian / Islamic architecture of Iran, thus the patterns on the stones and the garden around the monument are inspired by the geometric patterns of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque of Isfahan.

He also does not forget the well-known Persian gardens in the design of the fountains and the pools in the square surrounding the monument. Since the tower was built close to Mehrabad International Airport, it could not be taller than 45 meters, therefore it is more wide than tall. The width of the structure and how it stands on the ground gives an aura of stability to the viewer. Under the structure there is a museum and a number of galleries as well as a hall for theatre.

The people of Tehran have lived with their monument for 50 years. Initially named Shahyad (literally meaning 'King’s Memorial'), it has been a structure with great significance in the contemporary history of Iran. And from the beginning it had everything needed for a monument to become the symbol of Tehran. A unique design, a strategic location at the entrance of the city and near the airport, a plaza for gatherings and an aura of being a masterpiece to make it a cause for national pride and most importantly, the symbol of stepping into a new age.

Yet a great change transformed the tower’s function and name. The Islamic Revolution of 1979 swept everything in its storm of ideologic change. The monument was a place of gathering during the protests that led to the success of the revolution and afterwards, Shahyad was renamed to Āzādi (meaning 'freedom'). This urban structure became a scene of people’s presence in the turning points of history. The new Islamic state soon learned of Āzādi’s power and the tower built by an architect-in-exile after the revolution was always in the background of pro-government gatherings; in service of the regime.

But on the other hand, Āzādi still remained a sanctuary for anti-state protests, as well a refuge, a strong pillar for the public to raise their voices in an oppressive system. The happenings on this square, in front of this tower, have always revealed the pulse of social transformations of Iran. Most notably the 2009 Green Movement that shook the system to the core.

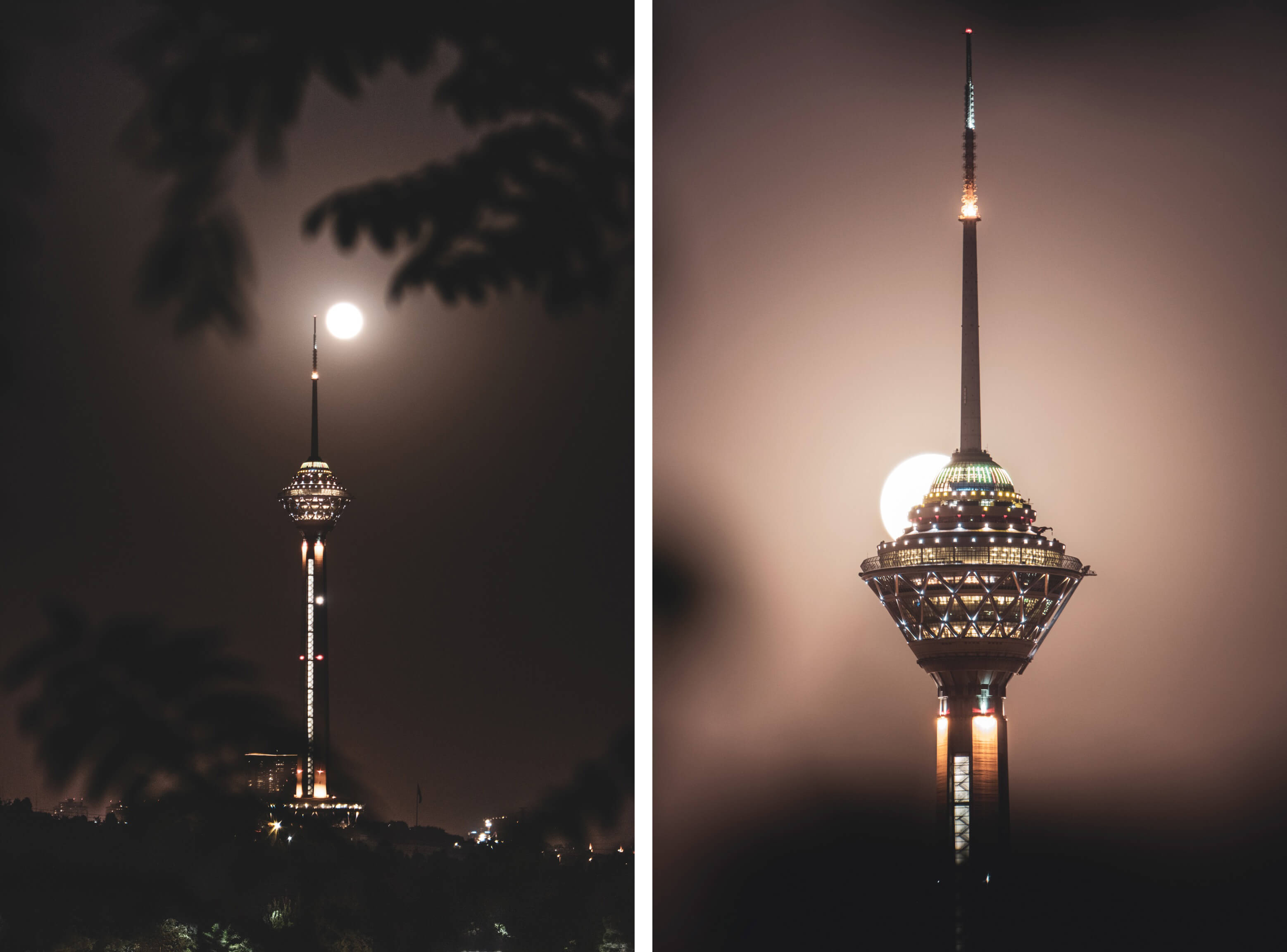

Although the post-revolution administrations have all used Āzādi in their pro-regime gatherings on important dates, yet the tower has always been too reminiscent of the pre-revolution times for their taste. Therefore, the Milad Tower was to be a replacement, to outshine Āzādi and project a modern Islamic identity to the world. In the 1990s, after the end of Iran-Iraq war, civil projects were gradually coming back on track to rebuilt a country that had experienced years of destruction and stagnation during the war. It was then that the proposition of a telecommunication tower was made, a tall structure with global standards that would be the symbol of the contemporary Tehran in the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution.

A location on the hills of Gisha district of Tehran was selected. The project that began in 1998 was named Milad (literary meaning 'birth'). Milad took more than a decade to complete, and with a cost more than two times the initial estimations its inauguration was celebrated in 2008 while it was yet to be utilisable.

Tehran’s 435-metre Milad Tower, that is visible from almost any point in the capital, is the tallest building in Iran and the sixth tallest telecommunication tower in the world. It is planted on a round base where the lobby of the building is located. A long column takes the visitors up by the elevators to the head of the tower where a mobile restaurant and other means of entertainment are located. Although it was said that elements of Islamic architecture have been referred to in the design, especially in the patterns used on the head of the tower, this structure is almost completely empty of historical, national, local or any other form of identity. It is a tower like any other; too big for human size, uninviting and made to compete with the global race of high rises, devoid of any local characteristic despite being located in an ancient country with a unique and long-lasting culture.

Although one of the defined functions for Milad Tower was to organise the telecommunication systems of the city, when the tower was inaugurated, this purpose was lost to the rapid pace of satellite technology. It seems that from the start Milad was behind its time. Experts also believe that with the existence of mountain peaks so close to Tehran such a tower was hardly needed in the first place. Milad was yet to be inaugurated when the criticisms rained over it. Most significant disapproval was to the idea of building such a tall tower on a well-known land fault in a city with high risk of earthquakes.

At first a complete alien in Tehran, the Milad Tower gradually found its place in the everyday lives of the citizens. Concerts, entertainment programs and restaurants attracted people and tourists to this tower. And hardly anyone can complain about the view of Tehran from up there.

Yet it seems that Āzādi is yet to lose its significance. In a recent survey, when asked which sites are the symbol of Tehran, 54 per cent of Tehran citizens named Āzādi as the sole symbol of Tehran while less than 34 per cent named the Milad Tower. However, air and noise pollution, water leakage and ignorance has caused tremendous damage to it. At its 50th anniversary, Āzādi began the Persian New Year with a hard shiver, as the firing of grenades for the celebrations rattled the structure and caused even more damage to its fragile body.

What exactly makes a structure a symbol of a city is unknown. It is not how it competes with its global counterparts and most certainly not the budget poured into a project. It is an intangible characteristic that sets apart a successful monument that is embraced by the public, from a failed one. By which structure will the future Tehran be identified? The Āzādi Tower, a memorial of the time of individual freedoms, or the Milad Tower that is ever present in the background of photographs? Only time will tell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Afra Safa | Published on : Nov 16, 2021

What do you think?