Threading new narratives: ‘Material Worlds’ pushes the boundaries of textile art

by Hannah McGivernNov 12, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Digby Warde-AldamPublished on : Oct 09, 2024

At the turn of the millennium, London was a city with an audible cultural buzz. In terms of music, fashion and design, it was experiencing a boom of a kind not seen since the high days of the 1960s. Its art world, too, had woken from a decades-long period of parochial torpor: boosted by Charles Saatchi, the Young British Artists were making enormous waves internationally, and a number of insurgent commercial ventures established over the previous decade—notably Jay Jopling’s White Cube—had endowed the city’s once-staid gallery scene with a new sexiness. The opening of Tate Modern, meanwhile, at long last gave the British capital a modern art museum worthy of the Centre Pompidou, the Stedelijk or even MoMA. Only one ingredient was missing: an art market of which to speak. London remained a minnow compared to New York, with few major collectors and only a fleeting presence in the minds of the wider international art world. Then, in the autumn of 2003, that all changed.

When the first edition of the Frieze art fair opened in The Regent’s Park that October, it marked a turning point in the London art industry’s self-perception. An arena-sized marquee displaying the wares of hundreds of galleries and dealers, it was an event on a scale to rival Art Basel, the most prestigious and longest-running of modern art fairs – but arriving as it did in association with a respected magazine, itself a champion of the punkish YBAs, it came with an added sense of excitement and irreverence. “To be honest with you, it was absolutely bloody massive,” one veteran dealer tells me. “Before Frieze, London felt sort of left behind […] but after, you suddenly had international galleries showing in London, and that’s when you started getting Hauser & Wirth, [David] Zwirner or whoever coming in, and it went from being a kind of provincial backwater to becoming part of the international art world.” The levee had well and truly broken: collectors and dealers from abroad poured into London, and in the two decades that followed, even through the dark days of the 2008 financial crisis, it seemed like scarcely a week went by without the announcement of a major new gallery opening.

There was the London Art Fair in Islington and there were the Olympia art fairs, which were a mixture of sculpture and furniture and objects. But when Frieze came along, we were very keen to be a part of that – it was at a whole new level. – Richard Ingleby

It would be foolish to attribute London’s elevation to art world capital to the presence of one fair alone: the opening of the aforementioned Tate Modern, the United Kingdom’s favourable tax rates and its easy access to the continental market, owing to its then-status as a member country of the European Union, may have played just as significant (if not greater) a role. It seems clear, however, that Frieze was the catalyst that launched the city into the major leagues. To understand how what is essentially a glorified tent in a municipal park could have quite so transformative an effect, it’s necessary to examine precisely what it had to offer the wider international art establishment – and how the art fair model at large might have changed the way that system operates.

For one thing, Frieze’s presence and the largely self-generated buzz around it ensured that already-established galleries in London could not miss out on the opportunity to exhibit there. For another, it allowed potential exhibitors from disparate geographical regions the opportunity to reach a new market entirely. “We participated in art fairs pretty early on in our history,” says Edinburgh dealer Richard Ingleby, who established his eponymous gallery along with his wife Florence in 1998. “The wider focus back then was on the United Kingdom, because we set this thing up in Edinburgh, where there is something of an art market but not really enough of one to support the sort of gallery we are. We always knew we had to look further afield and the obvious target was London.”

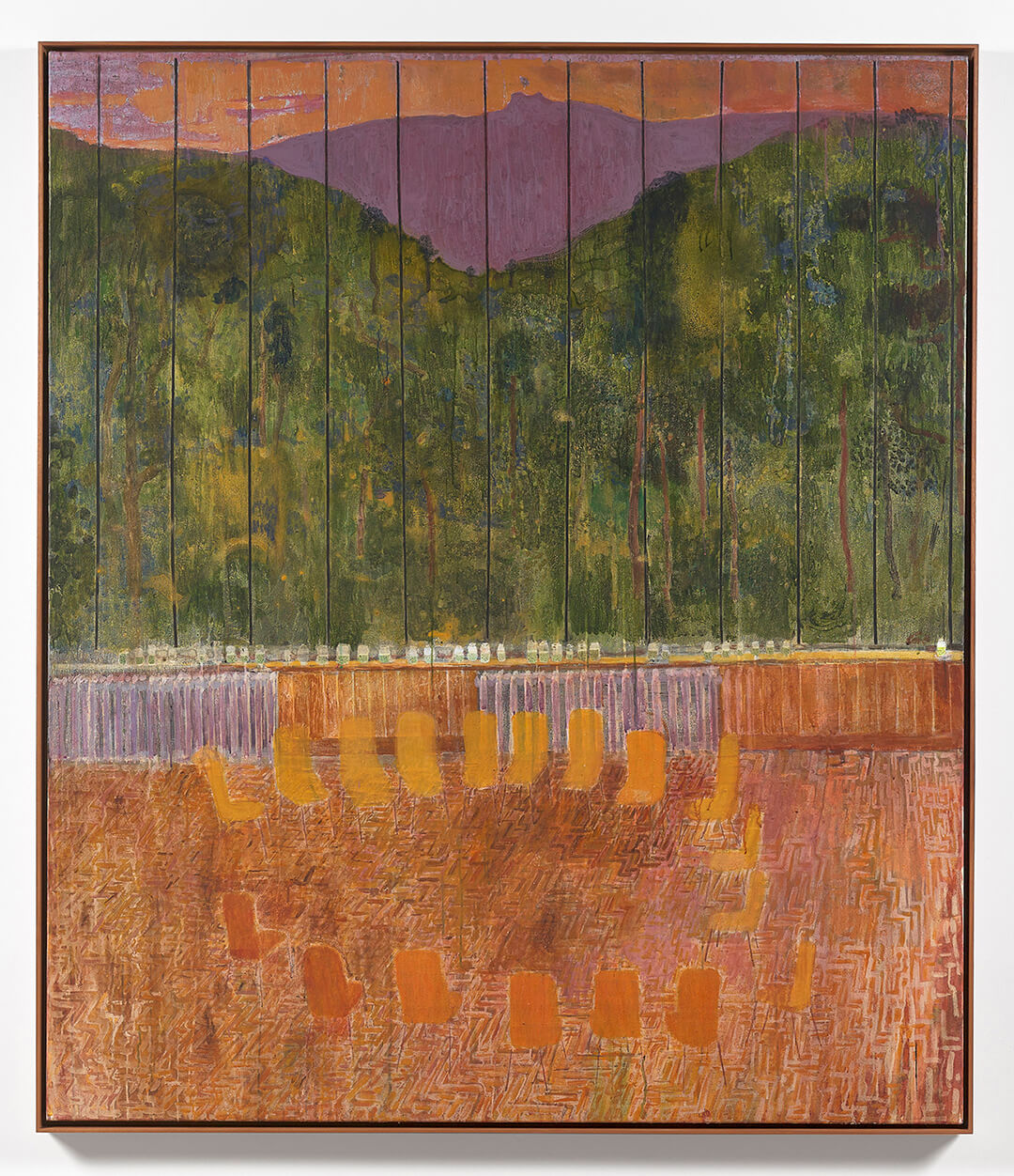

In its first years of operation, opportunities to exhibit in the city were few and far between, Ingleby admits. “There was the London Art Fair in Islington and there were the Olympia art fairs, which were a mixture of sculpture and furniture and objects. But when Frieze came along, we were very keen to be a part of that – it was at a whole new level.” For a gallery like Ingleby, which has since launched the careers of several major artists – notably that of the painter Andrew Cranston – the appeal was obvious: its dual mission is, in Ingleby’s words, “to take what we think of as the best work being made in Scotland and to represent that internationally [and] to bring international work into Scotland, so that it doesn’t become too much of a closed shop.” A fair on the scale of Frieze provides a model for the business to do the former, and often enough, open the necessary dialogues to enable the latter – at least, in theory.

In essence, a gallery cannot afford to pass up the opportunity to exhibit – but may sign up to participate in an art fair even in full knowledge that the odds of breaking even are slim to minimal. The collateral benefits – meeting collectors with whom they might seek to develop a relationship, curators who could enable institutional showcases for their artists, or indeed new artistic talent – are potentially enormous. A major fair in the present day attracts something between 60,000 to 80,000 visitors. Not all of them will be paying attention to every gallery, but for those who staff the booths, it still represents a chance to meet untold numbers of people, some of whom might be beneficial for the business or its artists.

It [Art Basel] wasn’t at all what I expected, but it allowed me to see the value of the art fair as a mechanism for how to create more awareness and potentially broaden one’s market. Jason Boyd Kinsella, artist

It could, broadly, be said that art fairs are less mercantile than their commercial demands might suggest – they can also be approached as networking opportunities, allowing a gallerist or artist from one metropole to forge ties with another. Yet it comes at a cost. “I’ve just got the bill for our Miami booth,” Ingleby says. “It doesn’t involve the lights, or any extras, so by the time we’ve paid for everything to build the booth, it’s well over $100,000. And then you’ve got to get everything there… so, for a big fair like that, there’s certainly no change out of $150,000.” Otherwise put, in the words of one former art world observer I spoke to for this piece, “from a dealer’s point of view, as I understand it, you’re f***ed if you do [participate] and double-f***ed if you don’t”.

An artist, however, might have a different point of view. Jason Boyd Kinsella, a Canadian painter based in Oslo, spent 20 years in the advertising industry before committing to art full-time. The impressive success of his trademark psychological portraits, formed of almost digitally precise basic shapes, has since seen him sign with Unit London and, beyond the UK, with Emmanuel Perrotin. He visited his first art fair, Art Basel, only in 2023, and saw his expectations upturned. “I’d never been to anything like it, but it was suggested to me that I should go and have a look to see what it was all about,” he tells me. The reality of the fair was something of a wake-up call. “I can’t speak for other artists, but personally, I don’t spend much time going to exhibitions and fairs and stuff like that […] but I don’t seek out what’s happening in the art world, and I think that’s something that’s left more to collectors than artists. So it was very helpful in terms of understanding my own context in the greater arts ‘ecosystem’, insomuch as it helped me reference just how many artists and how much art there is out there.”

Nevertheless, Boyd Kinsella took much from it. “Net, I found it to be a very valuable experience. It wasn’t at all what I expected, but it allowed me to see the value of the art fair as a mechanism for how to create more awareness and potentially broaden one’s market”, he says. “And that’s nothing but good news from an artist’s perspective – we tend to be quite inward-looking when creating our work and not really considering the audience that much.”

The Icelandic performance artist Ragnar Kjartansson goes further. “It’s like the de-glamourisation of art,” he says over the phone from Reykjavik. “I mean, there’s champagne and everybody’s wearing stilettos and all that, but it’s this sense that, you know, to see art so bluntly for sale…there’s something melancholic about it.” Kjartansson is not entirely critical, however. “The art fair… it is what it is. You think of Keats: ‘Truth is beauty, beauty is truth’. There is so much truth into this [art fair model], there’s a kind of brutality to it… it’s just there, laid bare. And we just somehow deal with that as artists, try not to let it control us, get us down, just kind of see it for what it is.” There is a further upside to this. As Jason Boyd Kinsella puts it: “just in terms of creating awareness for an artist, from people who visit the fairs – you know, maybe they have a couple of destinations of galleries that they want to see at a fair, and by proxy they end up discovering something new. [...] I think any artist can benefit from that because it just expands the parameters of your universe to include new, wide-eyed, interesting people. And that’s really valuable to any artist. So I developed a new kind of appreciation for what the mechanics of the art fair have to offer an artist and I think that to me was an empowering thing.”

For these reasons, one can understand why an artist might actively seek to participate. This, in itself, can be counter-productive: to be selected by their gallery for a fair, and to attract attention once they are there, our theoretical artist might well be tempted to start pursuing a certain type of practice – one exemplified by the kind of Surrealist-referencing representational paintings that have occupied so much floor space at present-day fairs. A gallerist who recently showed at a fair in the USA and did not wish to be named, explained it to me thus: hers was one of just two booths showing video art and small-format photography. Everything else showing, she said, largely consisted of paintings that were all but indistinguishable.

“Probably it must have some bad effect on art,” says Kjartansson of the art fair economy. “But then it’s kind of the fault of the artist, because if we’re always trying to make art that looks sellable, then we’re really dumb artists. ...I work with such wonderful galleries and I’ve never [been pressured to make anything that might play well at this kind of event.] And I always just think it’s the duty of the artist to make work, to never really think about selling anything […] That’s the magic that a good gallery makes.”

Beyond networking, there is a more informal social dimension to this type of event. Global as it is, the art world remains a small place, and for many in the business, fairs represent an opportunity to connect with old but seldom-seen friends – or indeed, to make new ones. Quite unprompted, Kjartansson springs out with one of the more heartwarming examples I’ve heard: “Me and my wife, we’d known each other before, but we fell in love at the Armory Show… so I always find art fairs quite romantic because of that, probably!”. The circus-like nature of these fixtures is something he is keen to stress. “It’s like a fairground thing, a romantic fairground thing.”

If the art fair model has entered a symbiotic relationship with the bricks-and-mortar gallery system, it should perhaps come as no surprise: whatever the status of the market—itself by all accounts dire in the art market’s traditional European and North American heartlands at the present moment—any dealership seeking a global platform simply won’t have another controllable means of being able to realise the ambition without shelling out for a booth. The kind of mannered, localised art world that existed in London before 2003 no longer exists in any territory likely to lure in collectors. For better or for worse, the fairs have seen art become just as globalised a commodity as any other.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Digby Warde-Aldam | Published on : Oct 09, 2024

What do you think?