2022 art recap: reimagining the future of arts

by Vatsala SethiDec 31, 2022

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by STIRworldPublished on : Apr 25, 2025

The proliferation of artificial intelligence and resultant media—images, videos, texts, music—is at the centre of a heated debate that takes into the fold questions of authorship, agency, creative expression and the very process behind that creative expression. We are at what happens to be the bare beginning of an age of digital ‘reproduction’, wherein, firstly, both the quantum of media we consume and are privy to is unbound; and secondly, the channels through which it reaches us are not only non-singular, but untraceable to a definitive origin. It is at the same time hugely quantitative as well as inherently reductive, as digital media relies on escalation—a ‘virality’, so to speak—of numbers, and that escalation relies upon reductivism. Everything that is to be proliferated like digital media must be producible, transferable, recordable and retrievable as data. The adage commonly goes: everything, every ‘work’ ever created, is bound to be a copy of a copy (of a copy). As users, consumers, bystanders, we are but witnesses to a phenomenon with the advent of artificial intelligence—now in a sophomore act of sorts—as we remain in a state of overstimulated submission.

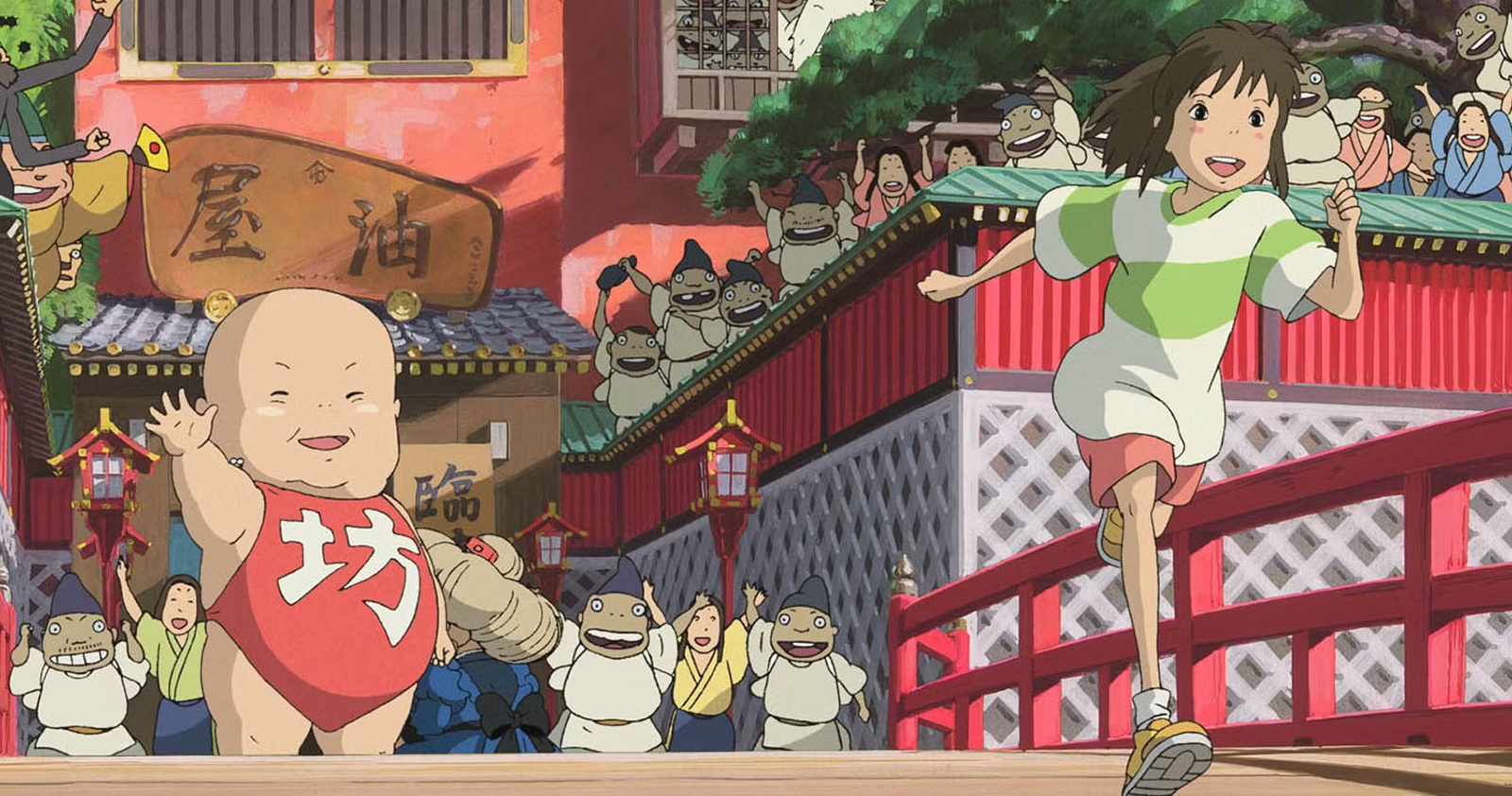

The onslaught of AI has already had wide-ranging, perhaps even irreversible implications for creative production in architecture, design and art. The latest furore from creatives stemming from this debate was directed towards social media, recently being flooded with AI images generated in the distinct animated style of beloved Studio Ghibli, leading to loyalists and ‘creators’ decrying the hollow fallacy of the ‘trend’. Despite millions hopping on the bandwagon, it was termed an act of vandalism and appropriation of the work of animator and filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki, whose career is distinctly marked by his painstakingly hand-drawn animated films. Between that and the GPUs at OpenAI melting, questions were raised, heated debates precipitated and both sides defended, albeit one more passionately than the other.

Apart from artistic and creative integrity, the perils of AI are further earmarked by huge security concerns. Whose data and how much of it feeds the aesthetic-image-generating machine? When does it—if at all—count for infringement? It took us just short of a decade to unwittingly move from an age of information to an age of misinformation, wherein, despite the “created with AI” disclaimers, the gambit of deepfakes, ‘inspired’ art and ‘impossible’ architecture continues moving towards unprecedented levels of refinement and impossible discernment. It is but a pivotal moment and several members of the editorial team at STIR take this opportunity to offer a collaborative weighing-in on the myriad questions this phenomenon raises, both as creative professionals and as the seemingly replaceable prefix to intelligence.

The recent spread of AI-generated Ghibli-style imagery underscores a broader trend in digital culture, a ‘natural’ progression if you will: the rapid creation (read: remixing), circulation and consumption of derivative, beloved content. This raises questions on authorship, appropriation and the dilution of artistic intent, particularly given that no consent was obtained from the original creator, Hayao Miyazaki. The viral spread of these images, met with both (mindless) fascination and informed unease, speaks to a cultural appetite for instant aesthetic gratification, often at odds with the ethos of the original work. It just is. It’s a rhetoric. It’s a prescient trend. It has potential. It raises concerns. Another exercise in digital commodification.

Some framed it as homage, others as unearned mimicry. No one claims it to be their art either. As filmmaker and artist Hito Steyerl has noted, much of contemporary image production exists in a ‘poor image’ economy—fast, shareable and often stripped of context and depth. Miyazaki’s condemnation of AI-generated art as “an insult to life itself” (NHK, 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki, 2019) now feels both prophetic and tragically overlooked.

This ‘trend’ seems to extend beyond AI: These images are largely created by those who can pay to deploy this tool—who may or may not be ‘artists’ and whose motivations might lie outside artistic ethics or understanding. This doesn’t seem to have much to do with AI-generated art anyway. Therein, the question of how we could reconcile obtuse aesthetic replication with artistic integrity, as homage slides into appropriation and access to such tools eclipses hard-earned understanding of creative craft, lingers.

In an increasingly homogenised ecology of images, the intent behind their creation ceases to have meaning. Images just exist, severed from intent and context. This has been particularly true of architectural media, which has long glorified the ‘image’ of architecture—sweeping visualisations and polished hero-photographs—along with the sole genius behind its conception. This rhetoric ignores the labour of those who actually execute buildings, including employees, draftsmen and engineers. The emergence of AI, more specifically generative AI, further complicates this relationship between image, intent and labour for the discipline.

The abundance of images is indicative of a tendency for people to forgo the process of creativity, instead relegating its laborious bits to AI; reproducing the world ad infinitum on whim rather than intent. Conversely, the use, or as tech pundits see it, the ‘enormous potential’ of the software in reducing the drudgery of somewhat archaic processes in architectural production—drafting, bookkeeping, specifications, documentation and the likes—to instead focus more or solely on ‘creation’ is bound to lead to an increase in workloads, if the emergence of CAD in the '90s was any indication. The use of AI, as it stands, seems to allow architecture to continue operating within the selfsame, self-aggrandising ecology that privileges the sole genius, while continuing to share troubling renditions of what architecture as a discipline means. How can architecture define itself through the labour of what it takes to produce a building, rather than the building (or its image) itself? If architects are to submit to (or unionise against) this phenomenon, how must we reconcile the two?

Craft is not defined by the perfection of its ‘end product’, but by imperfections that reveal a human touch, a distinctness; the subtle marks of effort that imbue work with warmth and personality. Studio Ghibli’s films embody this ethos, with every hand-drawn frame telling a story beyond the narrative itself. The painstaking process for Princess Mononoke’s (1997) 1,44,000 cells exemplifies how the organic, even flawed nature of craft deepens emotional resonance. By stark contrast, AI tools that “Ghiblify” an image in moments, or boundless other tools that “industrialise” and automate human processes in craftworks tend to strip this philosophy down to mere aesthetics. The machinic pursuit of precision erases the idiosyncrasies that make craftsmanship feel personal, leaving behind a technically flawless yet emotionally hollow product.

The heart of craft lies in its dialogue between the creator and material, between the work and its audience. Each adjustment, whether correcting a flaw or embracing it, adds to a narrative that is distinctly human. If we sacrifice these moments of unpredictability and discovery to AI, are we preserving creativity or merely consuming its polished facsimile? Without the human-centric aspect embedded in craft thinking, can craft remain craft, or does it dissolve into algorithmic anonymity?

All art is inherently mimetic—an imitation of an imitation—as Plato mused. But what makes AI-generated art troubling is not that it imitates, but that it does so without grasping what it mimics. AI-generated Ghibli art not just imitates the studio’s style but also evokes a feeling of nostalgia, albeit without any narrative and it does so without a knowledge of the studio’s emotional core. Perhaps the reason for concern is not that these images can now exist, but that we are actively creating them; that we crave emotional resonance without the discomfort of meaning.

Generative AI and generative art can offer us nostalgia on demand, but at what cost? It mimics patterns derived from massive datasets trained on energy-intensive systems powered by non-renewable resources. It is, thus, ironic indeed when it can, in mere seconds, replicate the visual language of a studio whose ethos is rooted in ecological consciousness and a profound reverence for the natural world, while completely disregarding the environmental costs of such a creation.

Although discussions on the value of labour, responsibility and mindfulness for consent—particularly in the wake of the recent onslaught of Ghibli ‘art’—are pertinent in reference to the malpractices undertaken to train AI models, it is essential to highlight and examine the depoliticised nature of the ongoing outrage. As it stands, labour and consent have been appropriated, devalued and exploited for millennia, with conversations around these values only propping up when culturally dominant subjects are on the receiving end of such manipulations, hence validating the Orwellian idea of hypocritical equality.

Against this reality, wherein we may continue to debate about the forms of creativity and labour that merit such outrage over their ‘elevated cultural value’ by being either widely beloved or prestigious beyond common reach, begetting protection from appropriation and duplication, it is incumbent to understand the political essence that very often gives meaning and value to these assertions. Similar to the politics behind such selective outrage, it is essential to gauge the politics that inform their creation when dissenting against their misuse. Only then can we truly begin to leverage the essentiality of protecting creative production for reasons that supersede an artist’s intellectual property rights and delve into motive. For instance, an AI-generated image of warfare and armed fanfare in the style of Studio Ghibli should draw outrage over its inherent propaganda and jingoism, as opposed to solely violating creator IPs, rendering the problematic misuse of creative dispositions in society at large. The ‘style’ in question is bound to lend a characteristic softness and innocence—devoid of any contextual narrative—to the final output, opening up room for manipulation and misinterpretation, thus showcasing a cautionary parable wherein individuals, brands, organisations in power and state-run establishments tend to use creative production to soften their image and sell a false sense of nostalgia and virtuosity, despite their inherently exploitative work.

Millions of people refashioning their personal pictures into Ghibli ‘art’ remains a testament to the contemporary phenomenon of living-room art being mass-produced for instantaneous gratification and to caveat ‘owning’ art. In the case of the recent debacle, though, it also infringes upon the ethical boundaries of ownership and consent. Disposable trends exploit the timeless—painstakingly elevated to that status—to feed the inherent urge to access it, own it. The short-lived Ghibli-fication wave was so potent that it not only inundated social media for days but also caused OpenAI’s GPUs to overheat and ‘melt’. People, irrespective of their familiarity with Studio Ghibli’s oeuvre and spirit, turned to AI algorithms to ‘acquire’ their manufactured piece of the iconic style; whether to become a part of the art or a fickle Instagram trend is arguable.

Instances such as this raise a significant question: is this the easiest way for the masses to access and ‘honour’ the art they love? Where do the boundaries between inspiration, appropriation and access lie and who defines them? When skill is replaced by trained AI models and the intent is minimised to appeasement sans the labour, what do we make of the result?

AI in the creative professions is frequently painted in binary strokes: an existential threat to creativity or a liberating tool. With AI models trained on existing artworks—often without consent—most view this as both an ethical violation and a form of cultural theft. In that light, solutions like ‘Glaze’ and ‘Have I Been Trained’ also act to shield artworks from stylistic mimicry by AI models in a digital ecosystem that often blurs the lines between originality and reproduction. Yet still, the debate invites a shift in focus: from individual authorship to collective responsibility in how our data is consolidated and assessed and from vitriol to vigilance while ‘consuming’ such art.

The disdain for AI in the arts isn’t uncommon, but often the deeper resentment is towards the conditions that make it feel necessary rather than the technology itself. AI, if used with caution and the aforementioned responsibility, doesn’t replace creativity; it assists in surviving the infrastructure that makes creativity feel secondary.

One major source of friction lies in tasks like writing artist statements or concept notes—demands that are mandatory for grants, residencies, exhibitions and academic spaces. These texts are often written in a language that is exclusionary and class-coded, privileging those with academic or institutional access. Traditionally trained artists, whose strengths lie in visual or material expression, struggle with articulating their work in academically sanctioned formats. AI-powered writing tools can help bridge that gap, providing support that isn't always available through mentorship or education. This evinces AI’s potential to ease systemic barriers and the culture of gatekeeping in the arts to commission creativity.

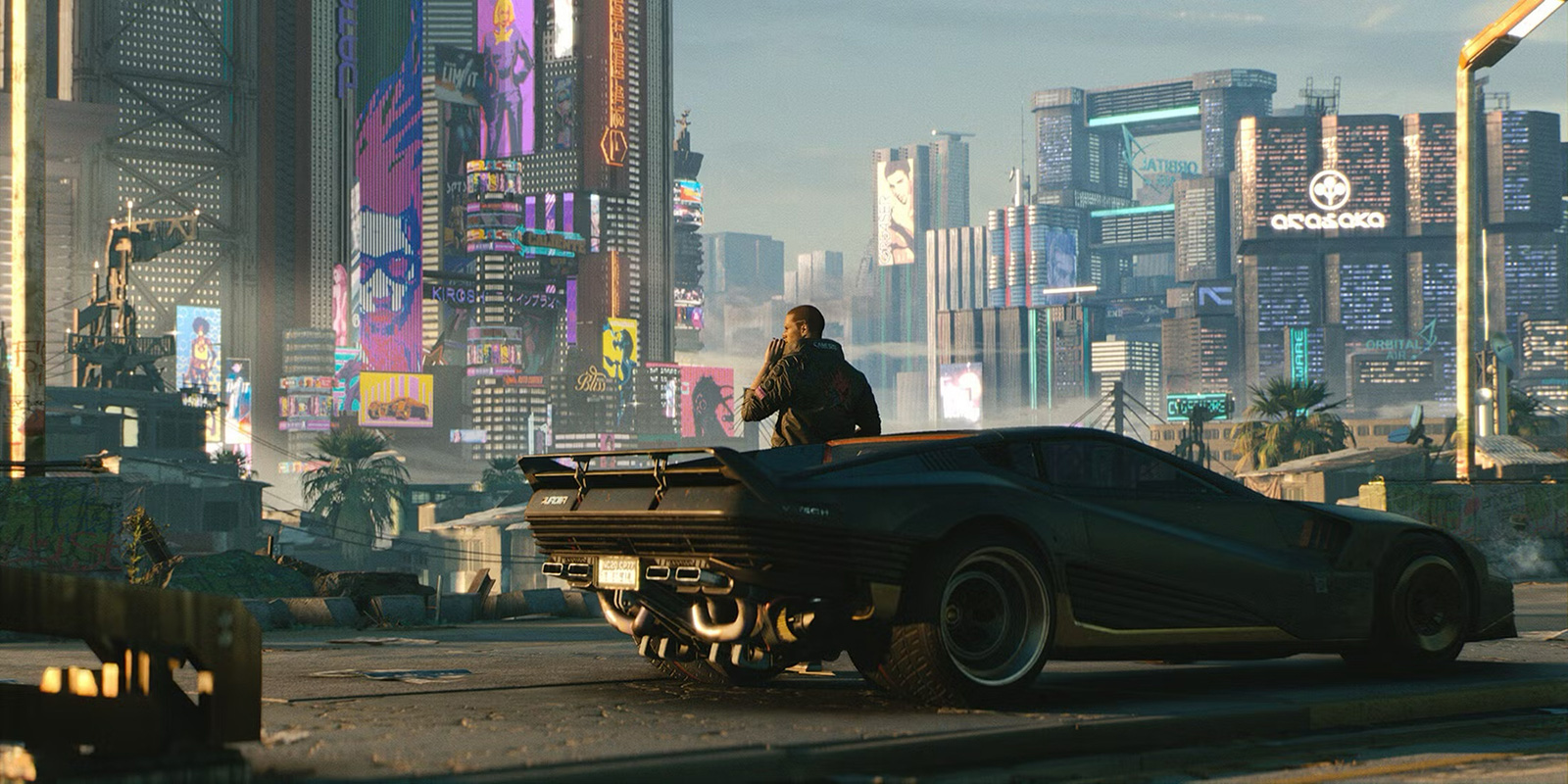

Immersive worldbuilding in mediums such as cinema and video games invites viewers to dwell in the creation instead of consuming it as a commodity; it encourages them to project their emotions onto it and potentially gain a deeper understanding of the art and a reflection of their own reality. Perhaps, there is something to learn from the video game industry’s utilisation of AI—for functions such as procedural logic, procedural content generation, animation and motion capture—to perform thorough, repetitive and tedious tasks, translating the creative team’s ideas into action instead of generating ideas itself. Many recent sprawling ventures in fantasy have expanded the veritable limits of the worlds they inhabit precisely by relegating the ‘boundary’ work to AI, including how an abundance of non-playable characters (NPCs) that make these worlds seem authentic would react. This is all geared towards giving players/viewers an immersive experience that places them at the centre, much like the creator is on the process side of things. It is a dynamic, rather sacred relationship that works both ways.

On the contrary, the recent AI-based bandwagon, which superficially interprets a style to create aesthetic imitations, reflects a stubborn adherence to aesthetic mimicry and growing disconnect from authentic expression. By blindly adapting and promoting algorithmically produced imitations, one perhaps engages in behavioural mimicry oneself, succumbing to the twisted, procedural logic of modern society, birthing a paradox of centrality. While an individual might believe they are creating ‘art’ using AI, their collective actions—imitative, repetitive and emotionally disengaged—exhibit algorithmic qualities, similar to the NPCs in a video game, programmed to simulate experiences instead of living them. It is a renunciation of how enough delineations from the norm along similar directions are bound to birth a new herd, a new norm, casting a shadow of doubt on the centrality of human experience itself.

As both rejoinder and consolidation to the myriad opinions expressed above, perhaps it bears prescience to return to basics. The first half of the compound term AI—‘artificial’—refers to systems that essentially emulate human intelligence; systems ‘trained’ through rounds upon rounds of consuming data consolidated over human years to make them adept at (re)producing that data and even foreseeing trends in machine seconds. There is, however, a certain predictability ingrained in this process, akin to the proverbial method in the madness. Where human intelligence is central to the process of creation, artificial intelligence relies on cycles of the same process to repackage data into seemingly ‘human’ outputs. The quintessential dichotomy then lies in the prerogative of what is deemed original and who must or can take credit for it. If human creation continues to be a self-feeding cycle, a sum of parts of everything preceding it imbibed through cycles of cognition and re-cognition, does ‘artificial’ production in creative pursuits, in a fraction of that time, lack potency simply by that virtue? Is it as simple as context, as being part of or responsive to specific coordinates in space-time? Is it as harmless as it’s made out to be?

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR.

by Chahna Tank Oct 15, 2025

Dutch ecological artist-designer and founder of Woven Studio speaks to STIR about the perceived impact of his work in an age of environmental crises and climate change.

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 14, 2025

In his solo show, the American artist and designer showcases handcrafted furniture, lighting and products made from salvaged leather, beeswax and sheepskin.

by Aarthi Mohan Oct 13, 2025

The edition—spotlighting the theme Past. Present. Possible.—hopes to turn the city into a living canvas for collaboration, discovery and reflection.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 11, 2025

The Italian design studio shares insights into their hybrid gallery-workshop, their fascination with fibreglass and the ritualistic forms of their objects.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by STIRworld | Published on : Apr 25, 2025

What do you think?