Local voices, global reach: Latin American art fairs gain ground

by Mercedes EzquiagaApr 28, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Ranjana DavePublished on : Apr 25, 2025

“The institution’s boundary is infinite,” X Zhu-Nowell tells me, pulling up an image of a Klein bottle, a four-dimensional non-orientable and boundary-free structure, on their phone, to illustrate its ambiguous borders. We’re discussing institutional models and audience sentiment in late March 2025 in the dimly lit business centre of their Hong Kong hotel. Since January 2025, Zhu-Nowell has been the executive director and chief curator at Rockbund Art Museum (RAM) in Shanghai, China, following two years as its artistic director. In their time at RAM, they have introduced new artists and formats to the programme, working out how to engage wider publics and smaller groups of local artists for whom the institution is a continuous incubation space.

Zhu-Nowell speaks of China from a place of intimate reckoning – as idiosyncratic, explosive and fuelled by the practice of a new generation of artists. The pandemic undid many things, they note, including a focus on China for its economic potential alone. This created space to work in granular ways, embedding what they call “private programmes” within the folds of institutional exhibition programming. “Each institution, each context, has a very unique condition. And that condition is how you can find the right programme for it,” they said to STIR.

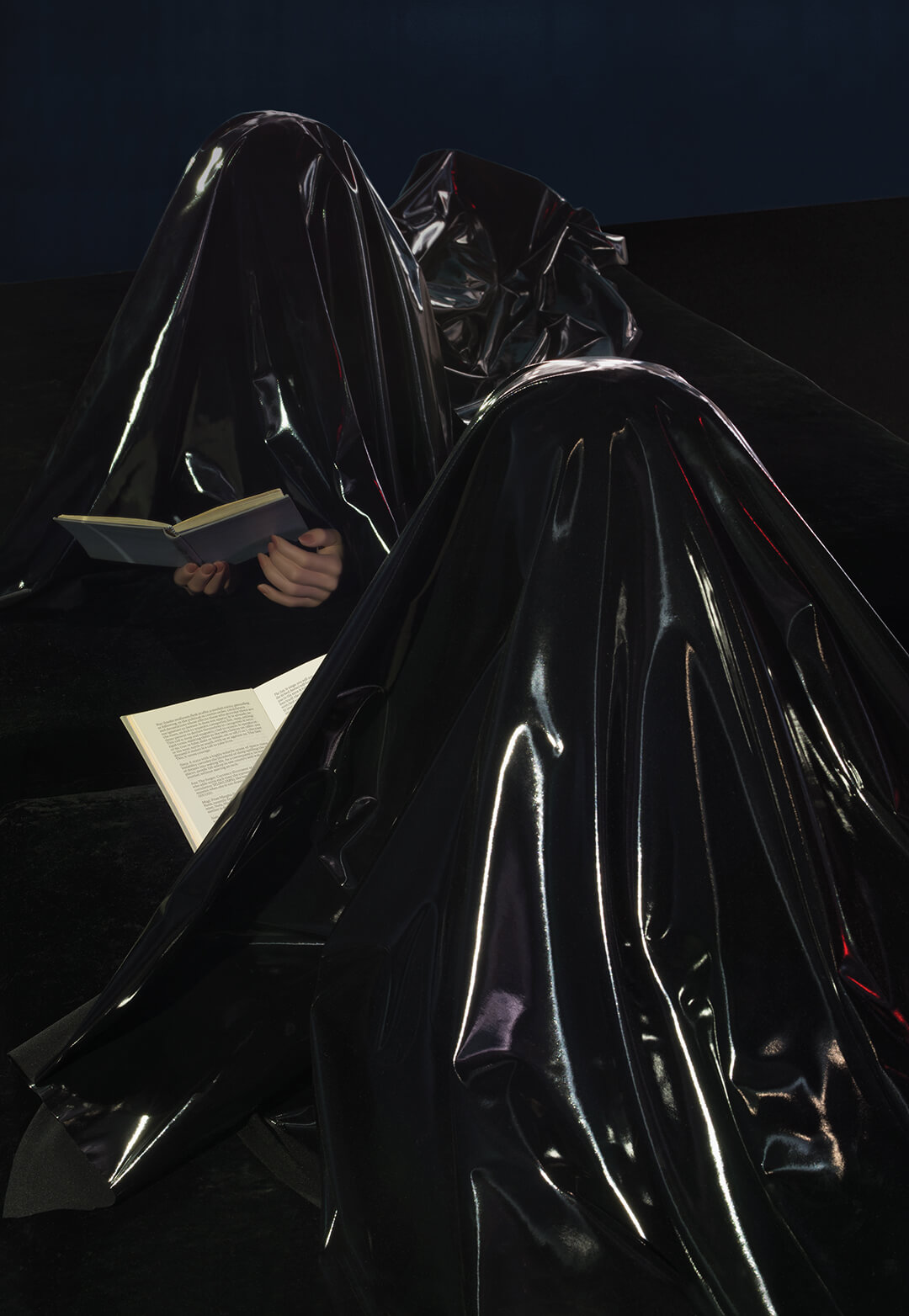

Previously a curator at the Guggenheim, Zhu-Nowell is responsive to the peculiar challenges of working in China – our conversation segued into how perceptions of monetary value defined the experience of museumgoers and the pre-eminence of painting as a visual art medium. Starting in May 2025, RAM features Serbian artist Irena Haiduk’s Nula, which will transform the entire museum into a film set, setting up an alternative economy as a comment on 1990s Yugoslavia and its staggering inflation rates. Visitors to the museum buy into the experience and play characters in a film during the exhibition.

For a brief spell, Zhu-Nowell ran an apartment gallery in their living room in Chicago, which helped them think about “how you don’t need to be in a big institution to create a community”. They are, in many ways, a millennial curator, channelling their turn of the century lived experience into their work. The 1990s China they grew up feeds into their curatorial vision for RAM. They read TikTok and RedNote reviews to make sense of what their audiences want – and how they express themselves. Edited excerpts of our conversation below:

Ranjana Dave: You’ve worked in the US and China - at the Guggenheim and then at Rockbund Art Museum. Were there key moments in your career that have shaped how you see the role of art institutions in society?

X Zhu-Nowell: There’s no [singular] way [to function as an] institution. For instance, at the Guggenheim, it’s a collecting institution [co-]founded by an artist, Hilla Rebay, who believed in the power of abstract art. How can a [collecting institution] relate to a much larger public? A lot of the work becomes mediating, also understanding where the gaps are. When you want to be responsible for a wider public, you also have to broaden your perspective. So my job at the Guggenheim was to open up their perspective and to open up the canon, open up the collecting initiatives. And that also taught me the importance of [the] archive and [the] institution, that it's never a static thing.

I came back [to Shanghai] during the pandemic. I wasn't really interested in working in China [before that] because I felt like there was a lot of excitement about China because of the money and the market – and the capacity for Western institutions to raise money in the region. I just felt like the conversation and the artists they were working with were dominated by the market influence. But then COVID-19 changed everything. People left, the economy went down. Younger artists, grassroots artists and young collectives started to emerge. And this is where I saw the ‘90s – the China that I loved. My research at MIT was focused on the early Shanghai artist-run spaces and then artist-organised exhibitions. Under a certain kind of pressure and circumstance, these things come back again. And I was interested in coming back [to be] in that movement, if you can call it that.

I made the decision…before China said it was going to open [itself up] to the world [again]. I was prepared for the worst. I also witnessed COVID-19 in New York as part of the Guggenheim team…[and] the lack of infrastructural support to allow institutions like the Guggenheim and others to adapt in this more diverse and complicated world. So [we] went into DEI related initiatives and had a lot of internal, you know, institutional reckoning. But I realised the model itself, the 19th century model, is the problem. So what Rockbund presented was an opportunity to exercise a new form, a new model.

Ranjana: Could you say more about that shift in the model?

X: As a curator, I am a formalist, in that I think a lot about structural forms. So if you think about 19th century institutions, it's a triangular model. A pyramid. You have the decision makers [at the top] and then everything trickles down. You have the board, which is the other pyramid. [These] two pyramids govern each other. And if we use design theory, what does that form afford? It affords a stable structure — stable financial systems and stable human resource systems so that the institution lasts a very long time. But it becomes this space where canonical narratives are formed.

For me, it is [important to see] what new structures and forms we can bring [to] institutions. The core of this is that we need to use the institution as a space to experiment on what that model could be. There are two models that I particularly love. One is a Klein bottle, which is a four-dimensional shape where the exterior and interior are on one surface. If we think about the infinity of the boundary, that will also help us redefine what we do, thinking about circulation. Another model I'm very interested in is the ellipse…[which] doesn't have a central point. It’s in constant motion. It is sometimes visible and sometimes invisible. In the context of China, a lot of the work we’ve got to do is not everything that everyone sees. It's about building the foundation, building relationships with artists and creating communities. I wanted to think about how Rockbund could be that for the local artist community, but also for the public. As an arts organisation, we have to think carefully about how we organise behaviours and social fabrics within the institution.

Ranjana: How do you find that balance between programming for the public and working with artist communities? Also doing things in different formats that are process-based, partially, but also public-facing…

X: We have programmes that are designed for the community…[like] Messy Things: A Think Bank at RAM – we're organising a closed-door conference in Shanghai with 20 people. And these people also work collectively, online, they're all scattered around the world and will create research that will live online and will eventually be public.

[For] the Curatorial Practices in Asia platform…this year, we chose to focus on China because there are so many new people organising [projects] in different cities that are not Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen or Hong Kong. They’re in the smaller cities. We wanted to bring a lot of people together and then have…very frank conversations, which I think is very important. But then we will do a day of public presentations.

If they pass through Shanghai or if someone is coming to do a site visit for a future show at RAM, we [invite artists] to do a lecture. And then we have a chat group of 100 people. I call it RAM Underground. After I got back to Shanghai in 2023, I realised that a lot of local artists don't talk to each other, or have no place to talk to each other. Because in Shanghai, [it is] different from Beijing, [where] everyone has big studios, you can gather. Spaces here are very small. If you go to restaurants, they're expensive. You need someone to organise [these interactions] and the institution should be doing that. So we deliberately give budgets to these events to do them consistently and continuously.

Ranjana: Are there any assumptions about contemporary art in Chinese society? How do these assumptions figure in popular culture, or in arts education, if at all?

X: There is the market and there are the state-run universities in China. I think both of them occupy a different space on the spectrum, but also have a very strong ideology attached to them. And our space [RAM] intended to carve out a small, tiny crack in that structure. There is a strong academic tradition, especially in the art school in Hangzhou near Shanghai. It influenced many artists and they have a [huge] student population. But then they were telling me that maybe only five per cent of those students become artists. Most of them work in advertising, creative agencies or design. There’s a [deep] understanding around tradition and history in art. But the critical thinking oriented contemporary art is something I think the “general audience”, which is not so general, [is] still trying to understand. I will say the audience [at our museum] is…very young and curious. They’re actually interested in research and a critical perspective. Through the work of artists and curators, we wanted to help them understand how we're all part of a much larger network. That kind of relationality matters to what we do.

I think there's a lot of assumption that the value of art is only monetary. Some museums, not to be named, will promote a show [by] saying that the insurance value of this show is [a certain] amount of money. So super expensive, right? People want to go see expensive work. This is not what we do. And this is why it's even more important to disrupt that economic mindset. I would say that I cannot generalise that for China, because it's really Shanghai. Shanghai has always been a port city, a trade city – a financial capital. So that kind of consumerist mentality [exists]. We want to play with that.

Another thing is that people sometimes consider only painting as art. We actually show very [few] paintings; the type of work we promote ends in media, performance, installations or interventions. And some people [asked], why is there no painting? There was always a question. Chinese, at least Shanghainese audiences, like to value their [spending] for the shows that they see, not [against] their experience or what they learned, but based on how many works they have seen. So if I do a show that has only three works, they'll [say], this is not good value. This is why bringing Irena [Haiduk] into the museum is so important, because that is precisely [what] we want to address. How we value [something]. How we desire.

Rockbund Art Museum is 15 this year. And it sounds very young, but it's pretty old for China. In 2014, we had a show with Ugo Rondinone, where the entire museum was painted in a colour gradient. But the work [inside the museum] has a performer dressed as a clown. So that was very shocking to [audiences] to see, “oh, art can just be that performance, or it can be a durational performance”. It’s not paintings or sculptures. That was 2014, but now everyone understands that. So they learn pretty quickly, but because the majority of society thinks [about value in traditional ways], it's hard to really shape them, unless they are [frequent] visitors to the museum. I think they will slowly get to understand the things we're questioning. But there are more and more young people who come all the time. I believe in the future generation, I think they're really inspiring.

Ranjana: You've spoken about imagining possible futures through the institution. But what does that look like in terms of crisis? And how do you balance out leaving the future/ futures open, but also not overdetermining them?

X: I've been telling a lot of people that…we're in a moment where we cannot project the future. Like it's actually hard to see. I can see five years. I don't know if five years [ahead] is considered the future. So what we can do is to focus on the present and being present; [it has] become the best way to survive…not having an expectation. A lot of our work involves digging into history. So it's about understanding the present more by looking into the past.

Ranjana: In an art world defined by market trends, what does independence look like for the institution? Is it financial freedom, curatorial freedom, or is it something that isn't as tangible?

X: I think it’s very difficult for an institution to be financially free in terms of how you define free, right? But I think for us, it's thinking. It's independent thinking, carving out that space where the majority of the social fabric is governed by two very dominant ideologies and how to carve out a crack, allow an independent perspective to exist. And also allow probing into the existing logic.

On the more practical side, our board does not intervene with what we programme, which sounds very normal, but isn't normal in the context of China, where a lot of times the owner is the director, is the curator, right? So I think we have to protect the independence of the curatorial thinking of the institution.

But of course, “independent” is not always “in isolation”. Independent is also interdependent. So finding a relationship with partner institutions, like-minded institutions and artists and curators and building a global network of these places and people is also very important to us.

Ranjana: What is the wildest curatorial idea you've ever had?

X: I have one for the Venice Biennale. But I don't know if I should tell the world about it. Maybe I should, because it's not going to be achieved. But I think it would be cool to do. I would love to swap places between the National Galleries and the Main Gallery. This is going back to the idea of collapsing…the boundary of a nation state. So if the main exhibition trades places with all the National Galleries and all the National Galleries have to negotiate their boundaries within the [main] exhibition space – and then the curator for the main exhibition gets to curate a show that is fragmented [across] different spaces around Venice. From Giardini to Arsenale and other collateral spaces around. That unsettles the 19th century model of what Venice has been about. And I think it's wild enough that it won’t ever be true because you have to negotiate with so many countries. But I think it would be a very interesting exercise for the art world to trade spaces, to think about: How can I think in your shoes? And how can I not always come from the positionality of – I want this? This is related to some of the programmes I'm slowly developing with other partnerships and other sister institutions. Instead of touring shows, can we think of trading spaces too? I would love to partner with some people and see what that could bring to each locality because that could be a very interesting experiment. So that’s pretty wild.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Ranjana Dave | Published on : Apr 25, 2025

What do you think?