Vibha Galhotra offers self-reflective perspectives on the climate crisis

by Manan ShahSep 02, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Ayca OkayPublished on : Feb 09, 2024

The forward-thinking artist Halil Altındere, born in 1971 in Mardin in Southeastern Turkey, has been working in art for over two decades, shaping storytelling through surreal scenarios and the projection of harsh realities. Known for his diverse artistic expressions across various mediums, Altındere collaborates with individuals from ballet dancers to police officers, exploring political, social, and cultural codes and resisting oppressive systems.

Graduating from Çukurova University's Painting Department in 1996, Altındere co-founded the artist collective Interdisciplinary Young Artists. He gained recognition for his Dance with the Taboos series, consisting of two printed images: an image of a 1 million Turkish Lira banknote with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on it, covering his face with his hands with a gesture of shame, and an image of Halil Altındere’s ID card covering his face at the 1997 fifth Istanbul Biennial.

Altındere completed a master's degree at Marmara University's Faculty of Fine Arts in 2000 and has been the publisher of art-ist magazine since 1999. Since 2002 he has ventured into curatorial work, contributing significantly to exhibitions worldwide. His works have found homes in prestigious museums like MoMA PS1, Centre Pompidou, MAXXI, MAK, and Les Abattoirs with the Guggenheim Museum recently acquiring one of his early photographs.

Shifting his focus post-2000 towards subcultures and daily life's extraordinary aspects, Altındere collaborates directly with diverse individuals. His solo exhibition in 2008 showcased a hyper-realistic wax sculpture of Mustafa Yağcı, a well-known street figure and a poet of the Beyoğlu district as Pala the Bard. The video Wonderland (2013), created with the Sulukule rap group Tahribad-ı İsyan and rapper Fuat Ergin, addressed the Sulukule urban transformation project which forced many ethnic minorities to shift from their origins by relocation with a significant loss of local identity.

STIR spoke to Altındere about the intricacies of his recent exhibition, A Brief History of My Last Three Years, at Istanbul’s Pilot Gallery and the convergence of politics, technology, militarism, and crypto art in his works.

Ayça Okay: Can you share your story with us? Was being an artist always part of your plans? What has predominantly shaped your practice?

Halil Altındere: I didn't have a dream of becoming an artist. In my second year of university, I became an artist to feel more liberated. In addition to my education at school, I acquainted myself with pop art, conceptual art, and Fluxus through books, catalogues, and international art magazines at the library I regularly visited. The concepts of ready-made and self-appropriation in pop art were a turning point for me. Upon delving deeper, Duchamp's urinal, the performative gestures of Dada, and the creative and political inspiration from the Situationists' 1968 movements captivated me right at the beginning of my student life. My first work created while studying painting was a photo collage titled Hommage to Toulouse Lautrec, dating back to 1994.

Ayça: Currently, the notions of displacement and the political factors driving such displacements are at the forefront of the art world. Even prominent biennials draw inspiration from concepts like the Sojourner by Antillean poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant or Claire Fontaine's work, Foreigners Everywhere. Can you briefly share your reflections on the concept of home and its significance?

Halil: This situation can be looked at from two perspectives: voluntary abandonment of home, i.e., voluntary exile, and displacement of people from their homes due to wars. The massive forced migration that erupted with the Syrian Civil War in 2011 and the developments following the Russia-Ukraine War in 2022 have sociologically and politically stamped the past decade globally. It resulted in the largest human migration since the Second World War. There was an invisible hierarchy for those forced to migrate as war victims. The impact of migration varied among different ethnic groups, revealing a significant truth about human rights inequality.

Forced migration resulting from war has been a poignant issue in the last decade, with visible disparities in the treatment of those affected. Ukrainian refugees were warmly welcomed in Europe with hot soups, while Syrian refugees faced pepper spray interventions.

The ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict continues to add to the uncertainties in the world. The reflections of these global developments are inevitable in the art world. I, too, have created works addressing displacement, home, homeland, and the representation of the other. In 2013, I produced the video Wonderland about the displacement of the Sulukule community. In 2016, the video Homeland was made in collaboration with Syrian rap musician Muhammed Abu Hajar. My work Köfte Airlines, depicting 45 refugees on an Airbus 300, and the video and installation Space Refugee, inspired by the story of Syrian cosmonaut Muhammed Ahmed Faris who sought refuge in Turkey, also touched upon these themes. The Neverland Pavilion installation created for the 58th Venice Biennale International Exhibition in 2019 also explored the representation of the other and the unrepresented.

Ayça: Your current solo show at Pilot Gallery covers a range of themes, including politics, technology, militarism, and crypto art. How have these themes evolved in your work over the last three years, and what drew you to explore these particular concepts?

Halil: In the exhibition titled A Brief History of My Last Three Years, I have created a series of works that revolve around three main axes questioning politics, technology, militarism, crypto art, cultural institutions, and the concepts of public-private space. In my recent productions, the new role of being a father in my personal life has permeated the works as a subtext, almost as significantly as the world-shaking pandemic.

The works during the pandemic period opened doors to rethink life/art through the lenses of "space" and the "circulation of art" and to explore new avenues (such as 1-minute short video platforms like Open Sea, where crypto art is exhibited). Meanwhile, the role of being a father marks a new era where Star Wars heroes, skateboards, and various animals infiltrate my art. My recent interest in traditional arts, especially "miniature" art, has resulted from using artificial intelligence technology as a personal assistant and actively involving it in the production process of the works.

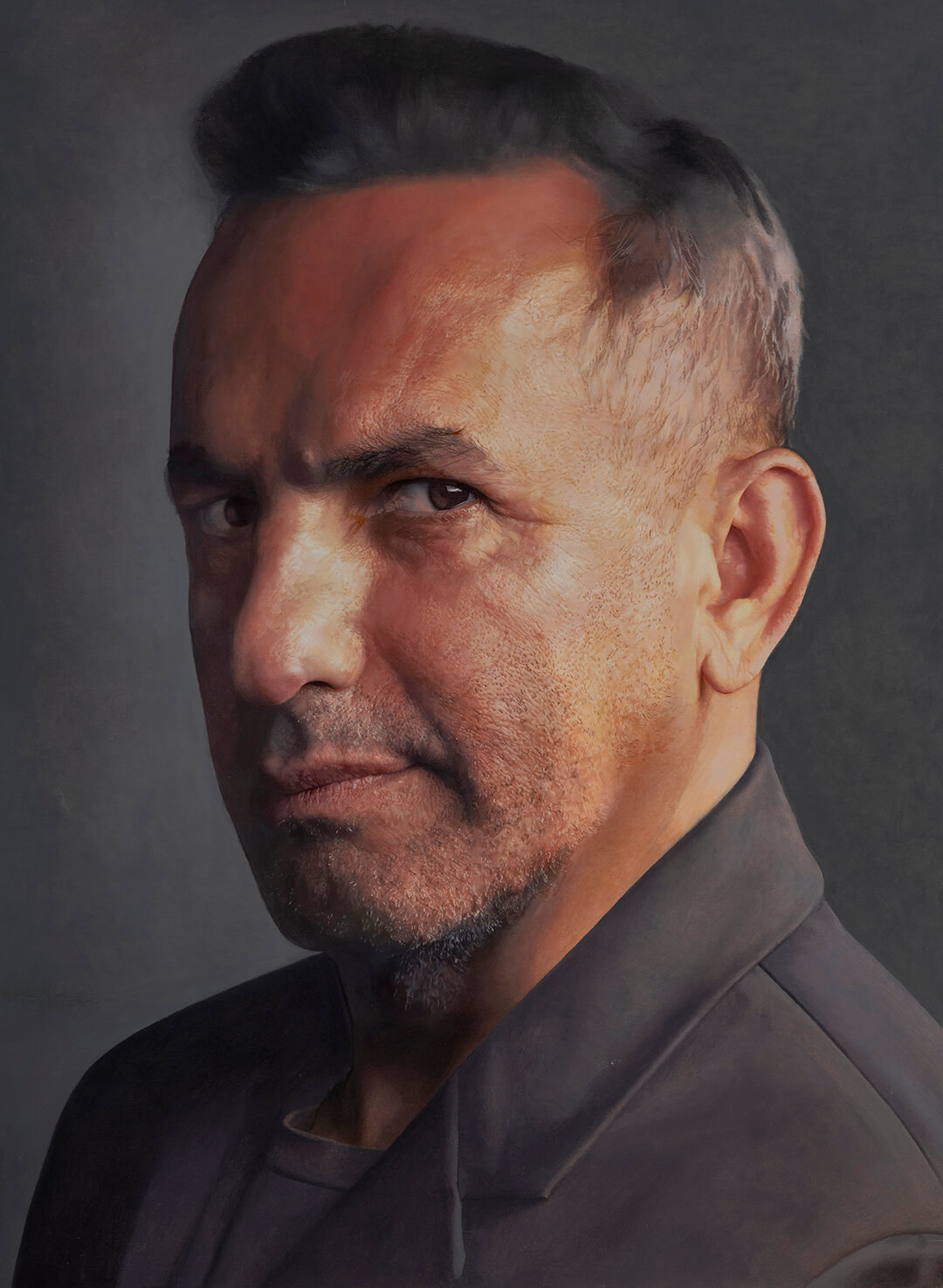

Ayça: Your self-portrait welcomes the audience at the entrance of the exhibition space. Regarding your work titled Portrait of the Sheikh, exhibited during the ninth Sharjah Biennial in 2009, what was the artistic intention behind it? Is your portrait a celebration of self or a show of strength? What has changed since your portrait work, Hommage to Toulouse Lautrec in 1994?

Halil: The self-portrait titled Hommage to Toulouse Lautrec, which I created in 1994, is one of the two self-portraits I have produced to date; the other being Hommage to Serge Gainsbourg. Defining these works as strictly self-portraits is challenging. My first work, Hommage to Toulouse Lautrec, was a homage to Toulouse Lautrec, whom I greatly admired during my student years in Adana, enriched by adding different layers as a gesture of respect. I produced the work using the photomontage technique. I was unfamiliar with the concept of appropriation or “self-appropriation,” which emerged entirely from my feelings without awareness. Hommage to Serge Gainsbourg was part of the Free Kick exhibition held in 2005 at the Antrepo, providing a free space for many artists, but eventually raided by the police, and its catalogues were confiscated. I used my art magazine, art-ist, dedicated to critics and opponents, to recreate a gesture that the famous French musician Serge Gainsbourg performed on television in 1984, burning a 500 franc note to protest high tobacco taxes.

Looking at this exhibition summarising the last three years, it is possible to see solid and ongoing connections with the past, and autobiographical impressions in many works such as magazine covers, plush drones, and portrait studies. Whether colossal Mao portraits in China or Sheikhs in Arab geography, in all geographies dominated by Socialist Realism, portraits of the region's leaders are among the main propaganda tools. In November 2008, I received an invitation to create a unique project for Sharjah Biennial 9, and then I went on a three-day trip to Sharjah. When I saw the portrait of Sheikh Sultan hanging at the entrance of the Sharjah Museum, I positioned a safe embedded in the wall behind it, giving the portrait an angle on the hinges to reveal this idea. The first portrait at the exhibition’s entrance, thinking of myself as a guest actor, is conceived with a logic where I reference myself.

Ayça: Your artistic practice is inseparable from your personality. Therefore, when people try to categorise your work, you always surprise everyone by shifting your focus. How do you perceive viewers' expectations regarding the 'radicalism' evident in the works you have produced in the past? Is this solely a 'Zeitgeist' issue?

Halil: This is also a matter of method and tactic. Some artists set a goal before them, and reaching that goal or achievement becomes a milestone. It's the end of the road and continues to be so for them. I was sure from the very beginning of my career that I didn't want this. Participating in Documenta, the Venice Biennale, or being featured in an exhibition or collection could be many artists’ most significant achievement and dream. However, these never felt like a goal or an accomplishment for me. On the contrary, I always believed that doing new things, researching, and learning each time were more exciting. Because when you set a goal and you reach that goal, it ends. Or if success for you means your work being sold at a high price or entering a significant collection, that could also end you. You end up having to respond to the market's demands. On the other hand, I always venture into areas beyond people's or the market's expectations, entering spaces where I feel happy and can improve myself through learning.

I want to expand myself beyond a specific field. I try different mediums for each exhibition. For example, bronze sculptures are predominant in this exhibition, and the rug is a new addition. I've always been interested in rugs but recently produced a related piece. Miniature, as a traditional form, is always an area waiting to be explored, and it can give birth to innovations within it. There are also two to three works related to it. Therefore, I believe in being open to surprises rather than expectations, and I believe in surprising the audience as well.

Ayça: Despite your numerous successful projects, much attention has been given to your proposed but unrealised works. Shall we discuss 15 Minutes of Freedom meant to be on view at the 12th edition of Documenta?

Halil: I participated in Documenta at an early age in 2007. It was a time when biennials were not widely embraced in Turkey. When I received an invitation from Documenta that year, I expressed to the curator my desire to create a project that would communicate with the city of Kassel and include the local people. For this, I visited Kassel twice for preliminary visits. While exploring the city, I was intrigued by an interesting architectural structure in the city centre. They told me that this structure was the Kassel Prison. I was very interested in it as a space. I wanted to see it and meet with the directors and inmates. Permissions were granted. I wanted to create a project related to what is happening in the city, not a temporary tourist exhibition for the city. And I wanted to do this project inside a building outside the exhibition spaces. For the project, 15 Minutes of Freedom, as a result of my collaboration with the inmates, we would train and rehearse with some volunteers. During the first week of the biennial, we would use these inmates as performers in some public space performances. However, inmates are forbidden to walk outside. Therefore, they couldn’t see the biennial. I wanted the inmates to see the biennial, at least the sculptures in public spaces. The content of our plan was as follows: A helicopter would land in the area. Then, individuals equipped with security constructions would cling to the legs of the helicopters, and then the aircraft would take off. However, they would not enter the venue, they would just take a 15-minute tour over the city, hanging in the air, especially over that sculpture park. This was a '15-minute freedom'. It would enable someone inside the prison who would never be able to see the exhibition because it is legally forbidden, but to see the exhibition by flying in the air. I had found such a loophole in the law. Lawyers said it would be fine to go out without touching the ground. This made sense to me. We did several workshops with the inmates. Just before the performance, a prisoner from a prison in Frankfurt, a city close to Kassel, had escaped and climbed onto the prison roof. This had caused a scandal. Upon this incident, the prison director invited me to Kassel and said they liked this project. They wanted to make my dream come true, but if they did, my dream could be their nightmare. So, they expressed that they did not want it. We cancelled this project, and shortly after that, we prepared and presented a video called Dengbêjs.

Ayça: Can you share details about your upcoming solo exhibition at the Sakıp Sabancı Museum in Mardin, which will continue the Turkish Military Drones Rug series?

Halil: The second and third parts of the carpet series I mentioned will be exhibited together for the first time in Mardin. In addition, there will be an exhibition curated by Nazan Ölçer, the director of the Sakıp Sabancı Museum, featuring various works I have created in different periods and showcased at many biennials worldwide. For example, the Neverland Pavilion installation shown at the Venice Biennale, Space Refugee exhibited in Berlin, New York, London, and many countries around the world, as well as works like Köfte Airlines displayed in numerous museums and biennials. The exhibition will include approximately 20-30 works. Additionally, a new video will be on view related to the city of Mardin.

by Srishti Ojha Mar 13, 2026

As media culture is transformed by the social internet and AI tools, the filmmakers of ‘Low Signal Feedback Loops’ adopt a new visual language to critique and interrogate it.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 11, 2026

The 82nd Whitney Biennial 2026 is a group show that reflects the ‘turbulent existential weather’ of the United States today.

by Srishti Ojha Mar 06, 2026

The British artist’s solo exhibition, ZOT at Varvara Roza Galleries in London, takes a postwar, postmodernist peek behind the curtain of artist studios.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Feb 27, 2026

Are You Human? brings together a staggering list of works that strive to question the consequences of our pervasive digitality but only engage with it superficially.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Ayca Okay | Published on : Feb 09, 2024

What do you think?