'Materialized Space' traces the tangled legacy of architect Paul Rudolph

by Sunena V MajuOct 23, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Vladimir BelogolovskyPublished on : Jul 17, 2024

Visionary architect I. M. Pei (1917-2019), who designed some of the most celebrated 20th century architectural masterpieces—the modernisation of the Louvre with the glass pyramid at its core, the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong and Miho Museum near Kyoto, is now the subject of a major retrospective at M+ in Hong Kong. It is a thoroughly researched full-scale institutional exhibition of this seminal architect’s oeuvre of more than 70 years. It is also the first show by M+ devoted to any architect.

During my conversation with the show's co-curator, Shirley Surya, she told STIR, "Our title, I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture reflects Pei’s view of not separating architecture from life. Architects should pay greater attention to life and derive solutions from it. One is not more important than the other. There is a symbiotic relationship between the two."

The idea to host the show was first expressed in 2017 when a double symposium under the rubric Rethinking Pei: A Centenary Symposium was co-organised by M+ with Harvard’s GSD, the architect’s alma mater and Hong Kong University’s Department of Architecture, where he was a frequent speaker. Focusing on Pei resonates with the museum’s identity, which is dedicated to collecting, exhibiting and interpreting visual art, design, architecture and moving images of the 20th and 21st centuries from a local, regional and global perspective. The initiative came from Aric Chen, the lead curator for design and architecture at M+ from 2012 to 2018 and who currently heads the Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam. Chen oversaw the formation of the museum—the building designed by Herzog & De Meuron, which opened in November 2021—as well as its design and architecture collection and programme. He approached Pei’s family about the potential exhibition a decade ago. In 2016, I. M. Pei personally endorsed the project.

Our title, I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture reflects Pei’s view of not separating architecture from life. Architects should pay greater attention to life and derive solutions from it. One is not more important than the other. There is a symbiotic relationship between the two. – Shirley Surya, Co-curator of I. M. Pei: Life is Architecture

The ambitious show, which opened on June 29 and is on view until January 5, 2025, features more than 400 objects: drawings, sketches, architectural models, maquettes of commissioned sculptures by such artists as Pablo Picasso and Henry Moore, photographs, letters, material samples, structural elements, newspaper clippings, films, and other documents. Original models are complemented by those built by architecture students at The University of Hong Kong and The Chinese University of Hong Kong. The vast material came from the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., the Pei Cobb Freed & Partners archives and the Estate of I. M. Pei, the architect’s clients, collaborators, and from institutional and private collections. The show is accompanied by a 400-page monograph with more than 400 illustrations, as well as anecdotes and articles by curators, historians and Pei’s collaborators. The book, which will go on sale in late July, adds many details to the last proper monograph, I. M. Pei: Complete Works by Janet Adams Strong and Philip Jodidio, published in 2008.

The book and exhibition are organised into six thematic sections/chapters. Pei’s Cross-Cultural Foundations is about the architect’s upbringing and education. Real Estate and Urban Redevelopment discusses the Chinese architect’s early work for New York developer William Zeckendorf and his firm Webb & Knapp. Art and Civic Form celebrates the architect’s museum projects and collaboration with artists. Power, Politics, and Patronage sheds light on his client relationships. Material and Structural Innovation highlights his inventive use of materials, structural design and construction methods across concrete, glass and steel. Lastly, Reinterpreting History through Design focuses on reconciling modern architecture with history, traditions and landscape. To emphasise the above topics, dozens of projects appear multiple times under different themes in a largely chronological order. There are study maquettes and structural diagrams next to archival photos, correspondence, photos of full-scale mock-ups, and contemporary views. The material is presented with the casual informality of an investigation project, not a glossy one-point perspective account.

Born in Guangzhou, China in 1917, Pei grew up in Hong Kong and later moved to Shanghai, where his father managed the Bank of China's office. Young Pei frequented the family’s garden villa retreat in Shizilin, Suzhou. It was while watching the rise of Park Hotel in mid-town Shanghai, a 22-story Art-Deco skyscraper, which in 1934 became the tallest building in Asia, that Pei was first inspired to study architecture. He left China for the US in 1935 to pursue his dream and acquired his Bachelor’s from MIT in 1940 and a Master’s at GSD in 1946 under Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. Pei initially planned to return to China, but the Second Sino-Japanese War kept him in the U.S.

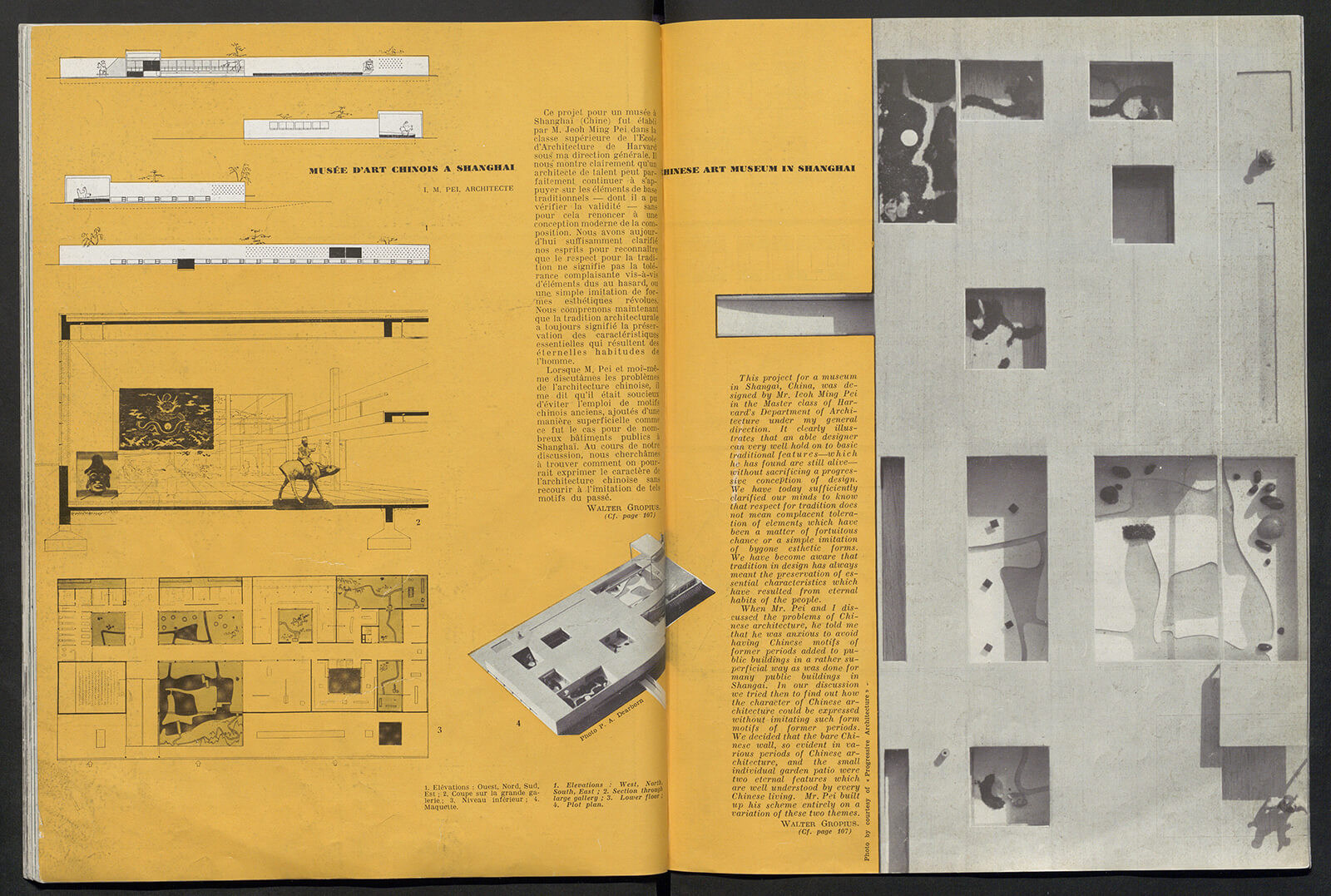

About Pei’s thesis project, the Chinese Art Museum in Shanghai, Gropius wrote, “It clearly illustrates that an able designer can very well hold on to basic traditional features—which he has found are still alive—without sacrificing a progressive conception of design… The bare Chinese wall, so evident in various periods of Chinese architecture, and the small individual garden patio were two eternal features which are well understood by every Chinese living. Mr. Pei built up his scheme entirely on a variation of these two themes.” Pei saw the limits of the language of international architecture. His insistence on bringing gardens and traditional elements into his architecture is evident even in his most abstract, sharp-edged works. His buildings are never uprooted; they are rather reinterpreted.

I. M. Pei & Associates was established informally in 1955 and became independent from Webb & Knapp in 1960. In 1983, he became the fifth laureate of the coveted Pritzker Prize. In 1989, the year Pei completed three of his iconic buildings—the modernisation of the Louvre, The Bank of China Tower, and the Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas—the firm was renamed Pei Cobb Freed and Partners. The architect retired from his practice the following year but continued to work as a consultant. His later prominent projects include the German Historical Museum in Berlin (2003) and the Musée d’Art Moderne in Luxembourg (2006).

In 1992, two of the architect’s sons, Chien Chung “Didi” Pei (1946-2023) and Li Chung “Sandi” Pei (b. 1949), founded PEI Architects. Their first commission—a very large mixed-use architecture in Jakarta—came through their father. When the architect was in his late 80s, the sons collaborated with him on the Suzhou Museum, built in 2006 within walking distance from Pei’s ancestral home in the historical heart of Suzhou.

The last section of the show and the book’s final chapter discuss the architect’s deployment of the Chinese garden as a planning device, which has been repeatedly and dynamically reinterpreted and integrated into projects related to China throughout his career. Surya reminds me that even Pei’s Bank of China, distinguished by its characteristic triangular framework and knife-like edges, is inseparable from its garden and cascading water feature that provides an apt buffer zone for the structure’s challenging parallelogram-shaped site complicated by the sloping terrain and busy highways that entangle it.

Among the show’s highlights, Surya cites a quote from Pei’s 1939 letter to his father written in English, “I don’t think I shall feel strange in a strange land.” The quote presents Pei not only as an architect but as a man who was adjusting well to living in the US, acknowledging difference, yet also wanting to engage that difference. The quote adds an important insight into their relationship and their multicultural backgrounds. Among other favourites, she points to a model from Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pei’s unbuilt Marina South Development Study that largely shaped the growth of the city’s iconic waterfront extending the original financial district, models that came on loan from the Louvre and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha; and photos of 11 of Pei’s buildings that were commissioned by M+ to be taken by seven international photographers during the pandemic.

Even after examining the show’s presentation and its monograph, the question of the origin of the architect’s instantly recognisable geometry remains. Where did his fascination with triangles and their repetition in various forms come from? Surya explains, “The use of triangular forms had been part of Pei’s architecture predominantly after he started working with glass and steel structures and the space frame. They did not occur when he was designing concrete buildings early on. In projects such as the Louvre pyramid, Pei’s choice of using triangular and pyramidal forms was due to it being the most efficient form—structurally strong while constructed with the least amount of material to be visually least obstructive.” In other cases, the curator points out that the use of a triangular form in the National Gallery of Art East Building resulted from having to maximise the use of the museum’s trapezoidal site. “It was logically informed by the site. But the three-sided galleries also created a dynamic viewing experience.”

His scope went beyond making a building look good. He felt responsible for the larger city. – Shirley Surya, Co-curator of I. M. Pei: Life is Architecture

Surya offered her view on another prominent example, "The design of the Bank of China as four triangular shafts with slanted ends to create an obelisk-like form can also be rationalised by the need for the tower, built on a tight site, to exceed the height of the nearby Norman Foster-designed HSBC Headquarters, on one-seventh of HSBC’s construction budget. As the tower rises, the tapered end of each shaft also enables it to be built higher in a way that meets the plot ratio. Its perimeter diagonal bracing was also a result of the use of a three-dimensional space truss whose members penetrated through the tower to unite the vertical planes of the building’s four columns through a fifth, central column. Again, the economy of means pushed Pei to use triangular geometry.”

Nevertheless, Pei’s inclination toward diagonals and triangles is evident in situations where he was free to use other means of expression, such as in the case of Dallas City Hall (1966-77) and unbuilt projects for Raffles International Center in Singapore (1970) and Kapsad Development in Tehran (1975). The truth is that once he discovered his affinity for triangular geometry, he claimed it as his own. It can be traced in all his subsequent works, explicitly or not. Even his Fragrant Hill Hotel in Beijing (1979-82), incorporated many traditional elements by refusing to assume bold forms, prompting many critics to label the project as Post-Modernist.

How do we summarise Pei's contribution to the culture of architecture? “I would emphasise his ability to read history and extract from it. Addressing regional context was his personal belief before it became a trend. His regionalism comes from his desire and deep understanding of the Chinese context. This was his reaction to Gropius's pure modernist approach, where there was little place for addressing diverse cultural and historical contexts,” Surya replied. “Then, he addressed buildings and their neighbourliness, paying attention to the widest context as in his Bank of China and the Louvre. These projects are profoundly urban—reorienting traffic, improving pedestrian connections, emphasising urban vistas, etc. Perhaps it was his training in real estate and urban development that gave him that perspective. He understood that you have to deal with many different constituencies on a city scale if you want your building to work in the long run and be an intrinsic part of the urban fabric. His scope went beyond making a building look good. He felt responsible for the larger city. He was a practising architect not known for theorising architecture, but he cared deeply about how our cities could be improved,” she added.

After working on this exhibition so closely the curator named the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado, as a favourite. “The competing factor for him was not another building; it was the mountains and what it meant to immerse himself in the environment.” She continued, “The epiphany for him was when he discovered the nearby cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado. NCAR became Pei's first major recognition. It looks unlike any other of his buildings, almost like an alien form. Pei cared so much for what it means to design in context. He extracted reddish-brown stone aggregate quarried nearby to compose the reinforced concrete. To colour the cement, Pei used sand ground from the same stone. So, even concrete was made not to look like concrete. Its resulting colour and texture evoke the erosion of nearby rock formations. Just as Pei described the Mesa Verde dwellings as 'embedded rocks and rooted trees,' traditional archetypes or historical precedents for him were not just something of the past, but a set of beliefs and fundamental design principles that have continuous relevance.” Finally, the curator added, “NCAR was also the main site for Woody Allen’s comedy Sleeper (1973). In a strange way, the complex evokes forms that are both ancient and futuristic.”

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Vladimir Belogolovsky | Published on : Jul 17, 2024

What do you think?