UnBroken at Camden Inspire 2025 proffered salvaged stories and second lives in design

by Asmita SinghOct 04, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Aarthi MohanPublished on : Sep 24, 2025

Architects are often remembered for building or imagining landmarks; a few are discursively reminisced upon for their ideals. Even fewer among them toe the fine line between the two. A stalwart by all means and a pioneer of the High-Tech movement in Britain, Richard Rogers proactively belonged to the last group. His Centre Pompidou in Paris, co-designed by him and Renzo Piano, was once nicknamed an “oil refinery in drag”, yet its outdoor escalators offered the best free view of the city making it one of Paris’s most democratic cultural spaces. In London, the Millennium Dome was intended to be temporary—a one-year pavilion; it still stands 25 years later, hosting concerts and spectacles every year. Such anecdotes reveal something central about Rogers—he was never interested in architecture as perceived in its inert form. His buildings, despite their often stark aesthetic, sought to work like living organisms, constantly re-energised by public use, reinvention and political ambition.

It is this quality that encapsulated Richard Rogers: Talking Buildings, the recently concluded exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. Running from June 18 to September 21, 2025, the show served as both a tribute and a critical foray into his work, offering the UK’s first retrospective on the architect since Rogers’ death in 2021. Conceived and designed by London-based designer Ab Rogers, also his son, the exhibition focused on eight projects that captured the architect’s ethos across more than five decades. As Ab explains to STIR, “This exhibition was conceived to focus as much on Richard’s personal and professional ethos and ideals as on the buildings themselves and the projects chosen were those that, I believe, best demonstrate the technical and political ideologies at the heart of his work.”

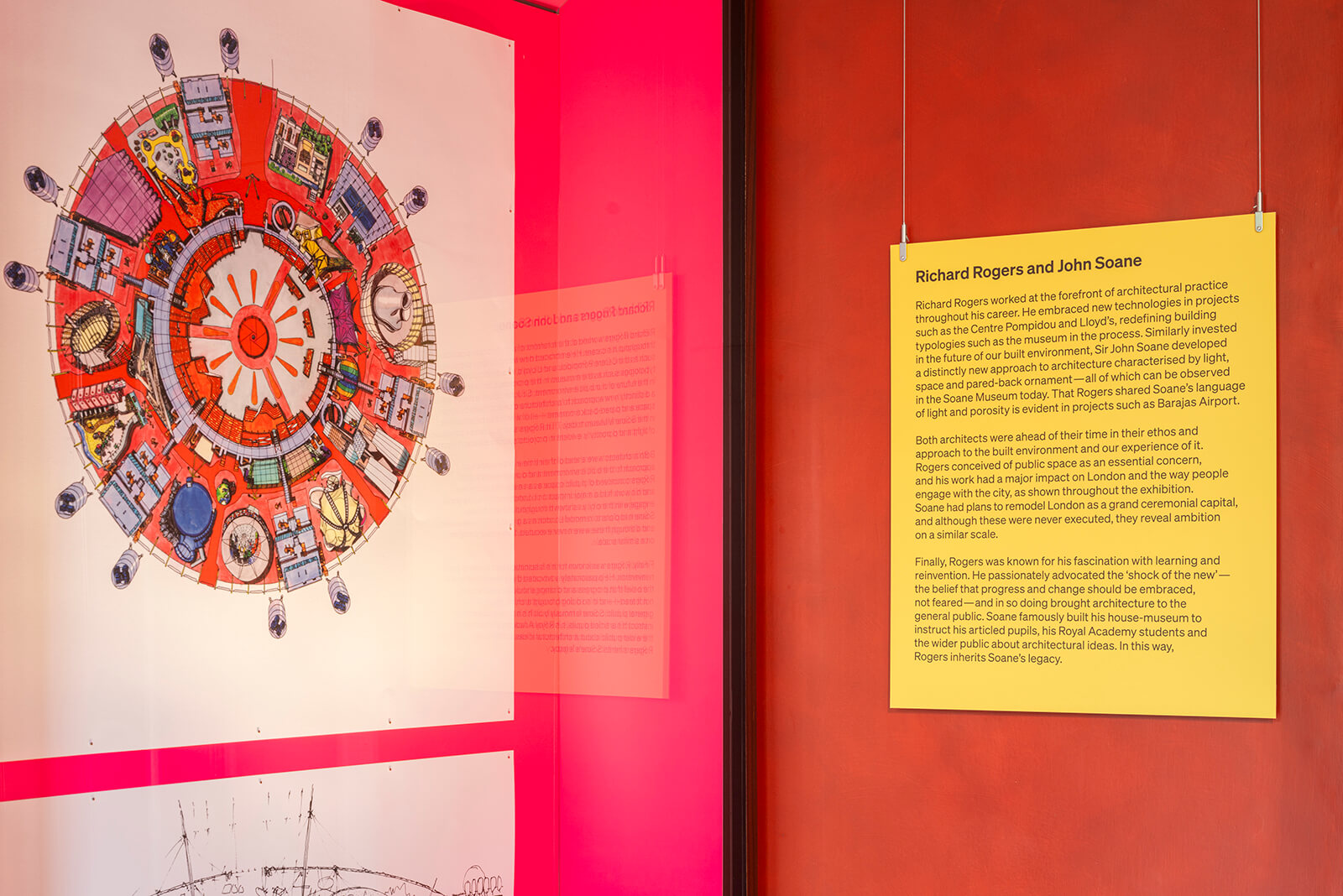

The setting of Soane’s house carries its own weight. Sir John Soane, the Regency architect who designed the Bank of England and transformed his Lincoln’s Inn Fields townhouse into a labyrinth of casts, models and antiquities, believed in architecture as storytelling. His home became his greatest experiment: part collection, part manifesto. Rogers admired Soane’s unorthodox outlook and the parallels that emerge with the show's staging on the site appear clearer. Both architects saw buildings as vessels of ideas, both used exhibitions as instruments of persuasion and both championed openness in design and in thought. Staging Rogers’ legacy here was less a matter of display than of dialogue.

The interiors of Soane’s Museum are famously crowded, leaving little space for conventional displays. Ab Rogers responded to the space and the brief with clarity. Drawings of his father’s projects were blown up to near-architectural scale, turning technical plans into diagrams of ideas. Anything not essential was removed. Brightly coloured Perspex models punctuated the rooms, while fluorescent pink backdrops set the material apart from the museum’s sombre architecture. Every decision was made to create immediacy. “We always strive to immerse the visitor in the culture of the exhibition we design,” Ab shared with STIR, “and to ensure the design language best embodies the curatorial narratives being communicated.” The result was an architectural exhibition that was both concise and bold, distilling decades of practice into vivid episodes.

The exhibition's journey began with intimacy. Rogers House, designed for his parents in the late 1960s, was a light, open container for domestic life, complete with bright yellow, green and orange interiors and a pristine white polyurethane floor. Its simplicity belied its radicalism; a prototype for living that blurred boundaries between everyday use and architectural experimentation. At the Soane, architectural drawings and models captured both its minimalism and its joyful palette. The Zip-Up House follows, developed with Su Rogers in 1967–68. Though never built, it proposed a prefabricated kit of parts, borrowing insulation panels from refrigeration trucks to create low-cost homes that could be quickly assembled and reassembled. “Buying clothes off the rack is the norm,” Richard Rogers explained at the time. “We wanted to do the same for the house.” At the exhibition, diagrams and models showed how this speculative project prefigured later explorations of flexible housing.

If these early works announced Rogers’ intentions, the Centre Pompidou made them public. Designed with Renzo Piano, the museum turned a corner of Paris into a civic stage. Its monumental arteries, painted in bright colours, coding services for air, water and electricity, made infrastructure part of the spectacle. In his competition submission, Rogers described it as “a place for all people, the young and the old, the poor and the rich, all creeds and nationalities.” At the design exhibition, Perspex models and enlarged drawings emphasised the clarity of that vision, while archival footage underscored how a project once derided as the “Notre Dame of the Pipes” became one of Paris’ most beloved institutions.

The Lloyd’s building remained another focal point in the exhibition. Completed in 1986, it pushed high-tech architecture to its limits by moving lifts, ducts and services outside, leaving the interiors flexible and uncluttered. At Soane’s Museum, large drawings highlighted the rigour of the design, while models showed its audacious presence in London’s financial district. The Millennium Dome, conversely, was represented as an emblem of impermanence turned permanent. Conceived as a pavilion for the year 2000, its vast roof canopy was derided at the time, yet its survival as the O2 Arena underscored the architect’s belief in adaptable structures.

Moving from grand staging and icons, the exhibition shifts to radical minimalism with the Drawing Gallery at Château La Coste in Provence, Italy, his last completed project before his death in 2021. A slender, opaque oblong, open only at its glazed ends, it directs the visitor’s gaze across the vineyards that surround it. Here, Rogers reduced architecture to a frame for looking. Photographs and models at the showcase presented it as a distilled meditation on perspective.

Not all of the chosen projects on display were buildings. The ‘Urban Task Force’, established by the UK government under Rogers’ leadership in the late 1990s, was given equal emphasis. Its recommendations for pedestrianisation, tree planting and the expansion of public parks reshaped London and continue to influence the city today, reflecting his belief that architecture remained inseparable from public policy and urban fairness.

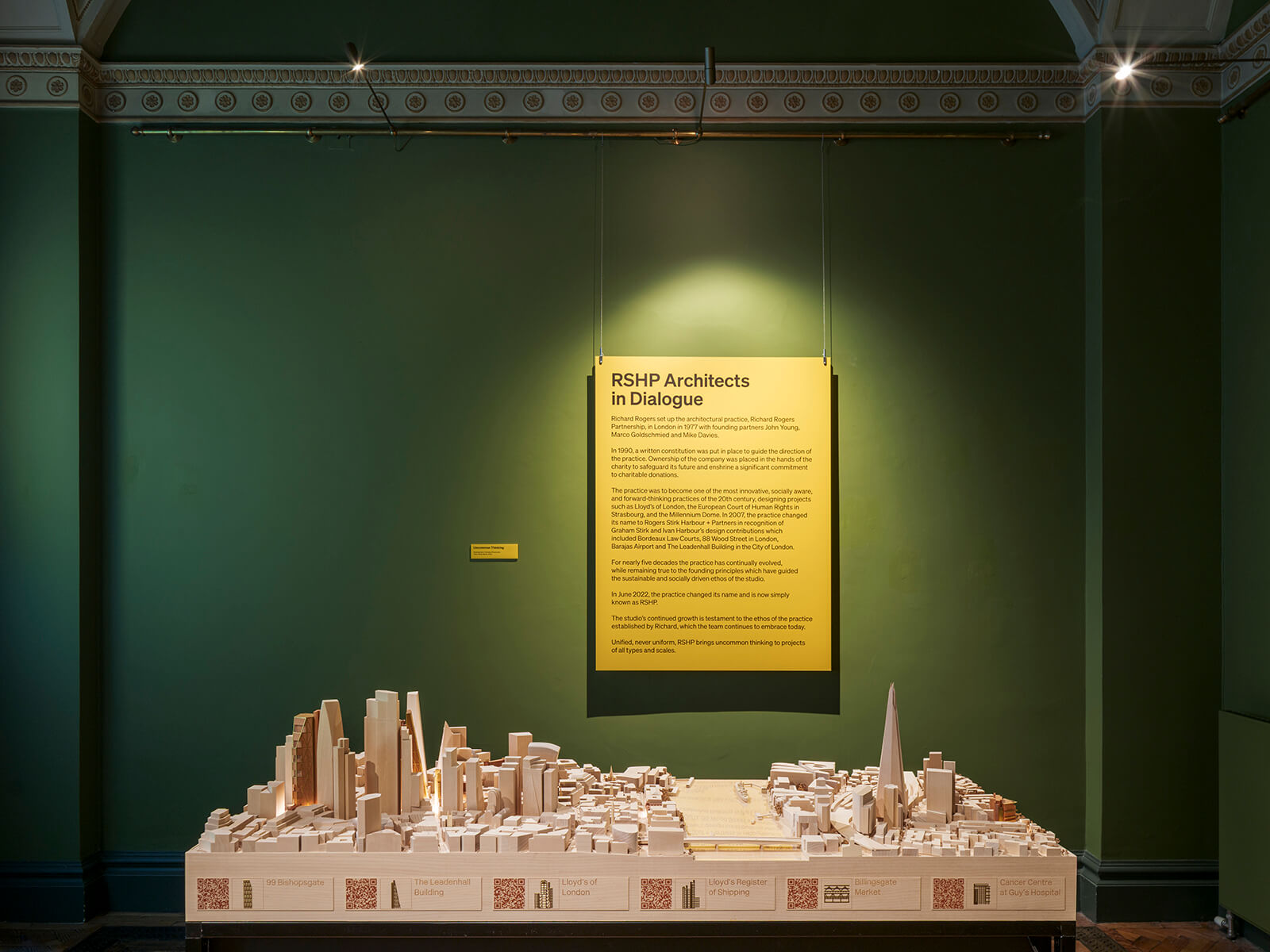

The scope of the exhibition naturally extended beyond Rogers himself. In the museum’s Foyle Space, a specially commissioned installation titled RSHP Architects in Dialogue presented the work of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, known today as RSHP. Through drawings and models, it demonstrated how the ethos established by Rogers continues to shape projects worldwide in the firm’s body of work. As John McElgunn, a senior director at RSHP, has remarked in the official statement, “Richard and his partners were radical, visionary and above all, humanists. Their work extended far beyond the act of designing individual buildings as they envisioned the city as a whole.”

Adding depth to these displays were two films by designer and filmmaker Marina Willer. One wove archival footage with new interviews to trace Rogers’ career, while the other reflected on his ethics and commitment to sustainability. Together, they give visitors a sense not only of what he built, but also of what he believed in.

For Ab Rogers, curating Talking Buildings was never solely a professional pursuit. Between 2006 and 2014, he collaborated with his father on exhibitions, including A House for the City and the Inside Out retrospective at the Royal Academy. Those experiences shaped his practice while deepening their bond. Reflecting on this, he recalls to STIR, “Richard lived through the boundary-less enjoyment of life, whether that was inhaling pasta pomodoro or designing the Pompidou Centre, for him, there was no separation. The same could be said of our personal and professional relationships; he was my father, my teacher and my collaborator and there are no lines between them.” For Ab Rogers, the extended afterlives of his father's designs were further reminders that Rogers' architecture was always a campaign for fairness, grounded in the belief that the city should be a shared project.

What shines through the exhibition is Rogers’ instinct to approach his work with the same fullness and vitality that he brought to life itself. He believed architecture could be joyful and political at once, ephemeral yet lasting, personal and collective. The exhibition arrangement echoed the sense of conversation more than a straightforward timeline; models that gleamed like arguments, drawings that read as manifestos and films that gave voice to principles still urgent today.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Aarthi Mohan | Published on : Sep 24, 2025

What do you think?