'kith and kin' wins Australia its first-ever Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale

by Hili PerlsonApr 22, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Ranjana DavePublished on : Mar 20, 2024

James Nguyen is a people person. His commitment to building relationships and making art with other people defines his exhibition, James Nguyen: Open Glossary, held at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) in Melbourne from September 16 - November 19, 2023. Born in Vietnam and based in Melbourne, Nguyen’s practice is interdisciplinary—he works in performance, video, drawing and installation. For this project, he collaborated with artist and curator Tamsen Hopkinson, community advocate and trainer Budi Sudarto, artist, curator and writer Kate ten Buuren, and tech worker and anthropologist Chris Xu. Nguyen was invited to develop and present the exhibition as part of an initiative by the state-run Copyright Agency Cultural Fund and key Australian art institutions, funding a new body of work and a solo exhibition by mid-career and established visual artists.

In an installation made with Sudarto, hundreds of formal, previously worn white shirts hang from wall-to-wall clotheslines, creating a winding path of laundry for visitors to walk through. The white shirts themselves represent a range: there are branded shirts, sharp whites fading into yellow pallor and shirts with frayed cuffs. Joined from end to end, they suggest worlds colliding with their strange intimacy—rows of donated white shirts, worn across cultural, social and geographic contexts. Charting a path through this maze of laundry, visitors hear snippets of recorded first-person accounts of the lives of queer migrants in Australia.

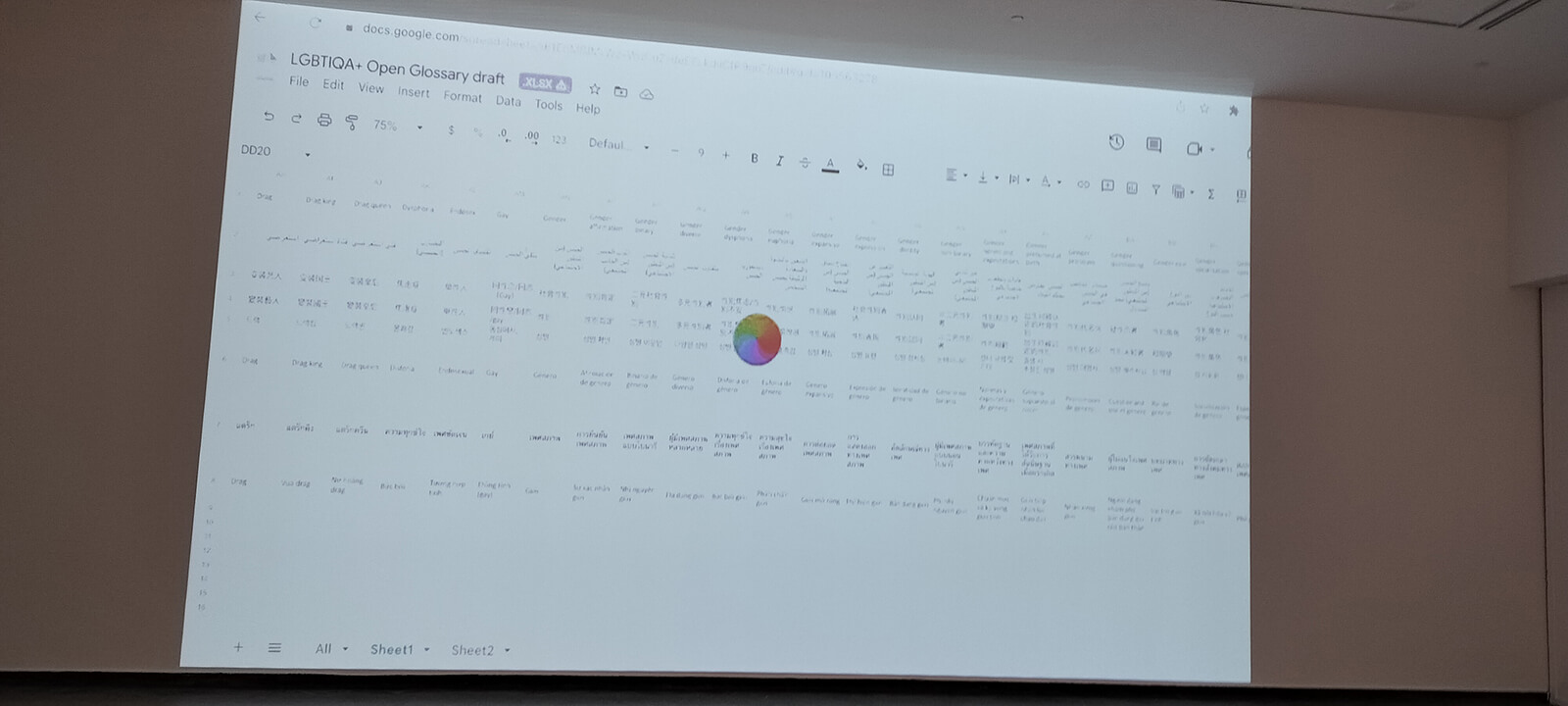

In another room, an online spreadsheet developed by Chris Xu collates LGBTIQA+ terms in various languages. Across much of the Global South, queerness is often discussed and theorised in English, in the absence of a wide vocabulary of equivalent terms in other native languages. These absences in language are violently mirrored in societal conventions and legal frameworks, often resulting in the omission of queer experiences and identities from public discourse. The gallery display features a single-channel video of a spreadsheet on hold, perennially frozen behind a spinning wheel cursor.

Visitors to the exhibition encounter ACCA’s distinctive rusty steel facade in the Melbourne Arts Precinct before being transported to the charged environments Nguyen sets up, bursting with ever-evolving questions and propositions and unresolved vulnerability. STIR spoke with Nguyen about his work:

Ranjana Dave: So much of your work draws on conversations you’ve had with your family and friends. Does your artistic practice become a way of processing life? How do you make sense of the world around you?

James Nguyen: I think art is a way for me to work out my place in the world. Because I love making art and doing art but I love talking about art and making art with other people. Through these relationships, I situate my life and ideas a lot better.

Ranjana: Did this emerge as a conscious approach? I'm also asking because with a formal art education, its approach to life can be very clinical in some ways.

James: I was a pharmacist for about six or seven years. I worked in palliative care and I loved it. I was helping people with end-of-life, preparing their families for it. But that started to wear me out. My high school friends noticed that I was depressed and they got me [into] these painting classes at the National Art School in Sydney. It is one of the most conservative art schools in Australia, where they train you to draw from the Western classical perspective. I think I decided to go to art school because it was almost an escape, a reprieve from the world. I started to make art that didn’t follow the classical or traditional formats—performance art, and video art. There were quite a few teachers who supported me. When I finished school, I started making videos and needed help from my family to record those performances. They were filming and trying to help me set things up; we were a team. That’s when I realised that when I made art, it wasn't just for myself; it was always in conversation with other people and always seeking and building on relationships that I had.

Ranjana: In the Open Glossary book (accompanying the exhibition), you talk about how you are expected to perform queerness, especially within institutional structures and how that doesn’t always align with the cultural and social expectations of the other communities you are part of—your family, your ethnic group. Drawing on poet and theorist Akhil Katyal’s framing of the 'doubleness of sexuality', there is a dissonance between the ways in which sexuality may be theorised and lived out. How do you negotiate that tension?

James: I come from a very conservative Vietnamese immigrant, Catholic family. Even now, sometimes they question if my queerness is just a phase. As I get older, it's really strange that every time institutions bring queerness into their spaces, there are expectations that it will be outwardly flamboyant, colourful and joyful. Queer life isn’t like that most of the time. Queer life is often lonely, quiet, it’s a lot of self-reflection; it’s not always a party. I resent that in some ways—to have exhibitions and shows in public spaces and galleries, you have to perform something that both the institution and the public expect of you. You have to perform your queerness. However, when you come home, you're with people that you love, all of that fades away and then you just become you.

Ranjana: Does reversing that gaze or reversing appropriation become a way of changing things?

James: When we talk about decolonisation, we are always having to turn all our attention to the West. They trade in our cultural objects and put them in museums and their homes, almost like decorative trophies. But people from the Global South like us have infiltrated so much, coming to Australia as refugees or migrants. What we’ve achieved within one generation, socially and economically, is incredible. So what happens if the shoe is on the other foot? As Westernised, privileged migrants and diasporic people, we don't necessarily have to be subject to colonial dispossession; we can disrupt it.

Ranjana: How did Open Glossary come together as a body of work?

James: The first work in the show is an “Acknowledgement of Country” I did with my aunt. A lot of migrants in Australia don't like to acknowledge that we are also colonisers, that we're living on Aboriginal land and we are benefiting from having come here. As migrants, we can also perform these acknowledgements. It's not only the responsibility of white people to do that. I had this amazing conversation with my uncle when he came to Australia. He said that it was part of our heritage to acknowledge spirits that have always existed in a place. People in several Asian cultures don’t always live in the places their families come from, because of war and displacement. Whenever we save enough money to buy a piece of land, we have to build a little shrine for the spirits that are already there. Every day, we put offerings into this outdoor shrine, in gratitude, to ask for safety, or to acknowledge that they exist. It’s not just a symbolic gesture; it’s a promise. Unlike people who just speak to these acknowledgements at events and then forget about it, we have to live these acknowledgements every day, we have to maintain these shrines. That does not happen in the West.

Ranjana: What about the white shirt installation which you put together with Budi Sudarto? I walked through it a few days after India’s Supreme Court delivered its marriage equality verdict, ruling that equal marriage rights weren’t a constitutional issue, but a legislative one. It brought back flashes of the Zoom feed from the courtroom in Delhi, which had these rows of lawyers wearing crisp white clothes.

James: That’s amazing. You can be so far from home but also be simultaneously connected and reminded of home via the colonial trope of the white shirt. As people move through the shirts, they start to be enveloped in these conversations, people talking about what it means to be a queer migrant in Australia. The idea of the shirts is to allow kids to enjoy themselves and to be able to touch things, but also for grown-ups to make their path through these conversations. To think of themselves in these white structures; it doesn't matter who you are, we've all been exposed to colonisation. We've all had to wear white shirts for work, or in the sweaty monsoon. So people see themselves in the installation as they encounter these conversations that they can't fully understand because they're not translated.

Ranjana: You put the glossary project on hold because of the fear of it being vandalised and made vulnerable to violence. Can language also be a practice of care?

James: In 2016, Chris Xu, a queer anthropologist in New York, set up a Google document called Letters for Black Lives. They wrote a letter to their parents in English explaining why they wanted to stand with Black African Americans. Within two weeks, their letter was translated into 50 Asian languages. I'd been talking with Chris about making a glossary. A lot of us in the arts are well-versed in queer theory. But then when we go back home and we talk to our parents about it, our parents don't understand our English terms for queerness and gender. When I go back to Vietnam, I realise I'm not part of the queer community there because I don't speak their language anymore. The only Vietnamese I can talk about my queerness in is the one I inherited from my parents, which is from the 1970s and is very patriarchal and homophobic. So Chris and I thought about our bodies. We make a list of basic terms like lesbian, gay, trans, queer, gender—all the simple terms that we take for granted in English. However, as we were putting the Excel spreadsheet together, we were seeing anti-trans and anti-drag movements emerge. People were protesting against drag queens reading stories to children. A lot of the communities that we were working with to translate this document were being bullied and bombarded online. That’s why we put the spinning wheel on it. We also realised that we could use ideas from queer protests, like the people who were turning up in angel costumes to shield and protect drag queens at libraries. We made a corridor of angel costumes, embroidering some of the words from the glossary into them, so you could read and touch and feel them.

Ranjana: Somewhere in the show, there’s also a conversation unfolding among your collaborators.

James: Through friends and lovers, I learned that there are basic words that are common throughout the Asia-Pacific. It’s incredible to think of all that oceanic distance and how there are words that reverberate across all these cultures. One of those words is hui, a gathering or a coming together. So Tamsen (Hopkinson) and I wanted to create a room that was like a tribal longhouse. Every time ethnic people get invited into white spaces, we're expected to wear our traditional costumes, bring out all the grass skirts, make lots of food for people and make everyone feel woke and accepted. Instead, we decided to make a space of contemplation. We used ash from a Maori and First Nations collaborative that Tamsen is part of. We placed six anti-fatigue mats along the edges of the space, inviting people to stand on them. They were an acknowledgement of the work that goes into maintaining a meeting place, an exhibition, or any social space. We wanted to make people take their shoes off so that it slowed them down, so they could reflect on their own place in these exchanges. It’s a great meeting place; you see everyone sitting around the perimeter of the square. Everyone is equal.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Ranjana Dave | Published on : Mar 20, 2024

What do you think?