Serendipity Arts Festival 2024 highlights the transformative power of the arts

by STIRworldNov 27, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Rémy JarryPublished on : Aug 14, 2024

Gathering 73 artists from 30 countries, the 15th Gwangju Biennale will enhance the legacy of pansori (판소리), a traditional epic chant inscribed on the Intangible Cultural Heritage list by UNESCO since 2008. Artistic Director Nicolas Bourriaud identified it as the epitome of his curatorial vision for the Biennale, articulating sound and vision as a form of storytelling performed by a singer and drummer. With colloquial origins, pansori also carries the soul of the Korean people and an ideal of justice that is at the core of the Gwangju Biennale. This crossover remains very consistent with Bourriaud’s achievements as a curator and art critic, empowered by interdisciplinary collaborations, including projects in the culinary arts with chef Ivan Brehm in Frozen Forest for Abu Dhabi Art last year. As part of his “curatorial grammar”, Bourriaud conceives an art exhibition “like a movie” and compares curating to “gathering musicians for a concert”. While his book Relational Aesthetics (1998) explores the relational nature of contemporary creative work, Postproduction (2001) extends the figure of the DJ from music to visual arts and The Radicant (2009) highlights the process of identity construction. Additionally, Bourriaud often sources ideas from anthropologists, such as Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009) or Eduardo Viveiros de Castro (1951-), to question ethnocentric narratives.

A significant portion of the artists in the Biennale (who skew younger, with two-thirds born after 1980) have already worked with Bourriaud, such as Bianca Bondi, Peter Buggenhout, Anna Conway, Loris Gréaud, Agata Ingarden, Agnieszka Kurant, Max Hooper Schneider, Ambera Wellmann and Phillip Zach, all of whom were included in Planet B: Climate Change and the New Sublime, organised in 2022 by the curator during the Venice Biennale. As Madang: Where We Become Us, the 30th-anniversary exhibition of the Gwangju Biennale remains on view in Venice until November 24, 2024, Nicolas Bourriaud introduces the upcoming biennale and reflects on his art criticism and curatorial career. Excerpts from a conversation with STIR.

Remy Jarry: What’s your core concept for the 15th Gwangju Biennale?

Nicolas Bourriaud: I curated many exhibitions about the Anthropocene, such as The Great Acceleration for the Taipei Biennial in 2014 and The Seventh Continent for the Istanbul Biennial in 2019, exploring how artists were influenced by climate change and how it has impacted their vision of the world. I decided to shift and think in more formalised terms. In my research process, I also discovered pansori, this amazing traditional opera created to accompany shamanistic rituals in the region of Gwangju during the 17th century. Pansori is both about space and sound, ‘pan’ referring to the public space and ‘sori’ to the noise, the rumour or the music coming from it, providing a very vernacular metaphor for the biennale.

Remy: What have been your criteria for selecting artists for the 15th Gwangju Biennale?

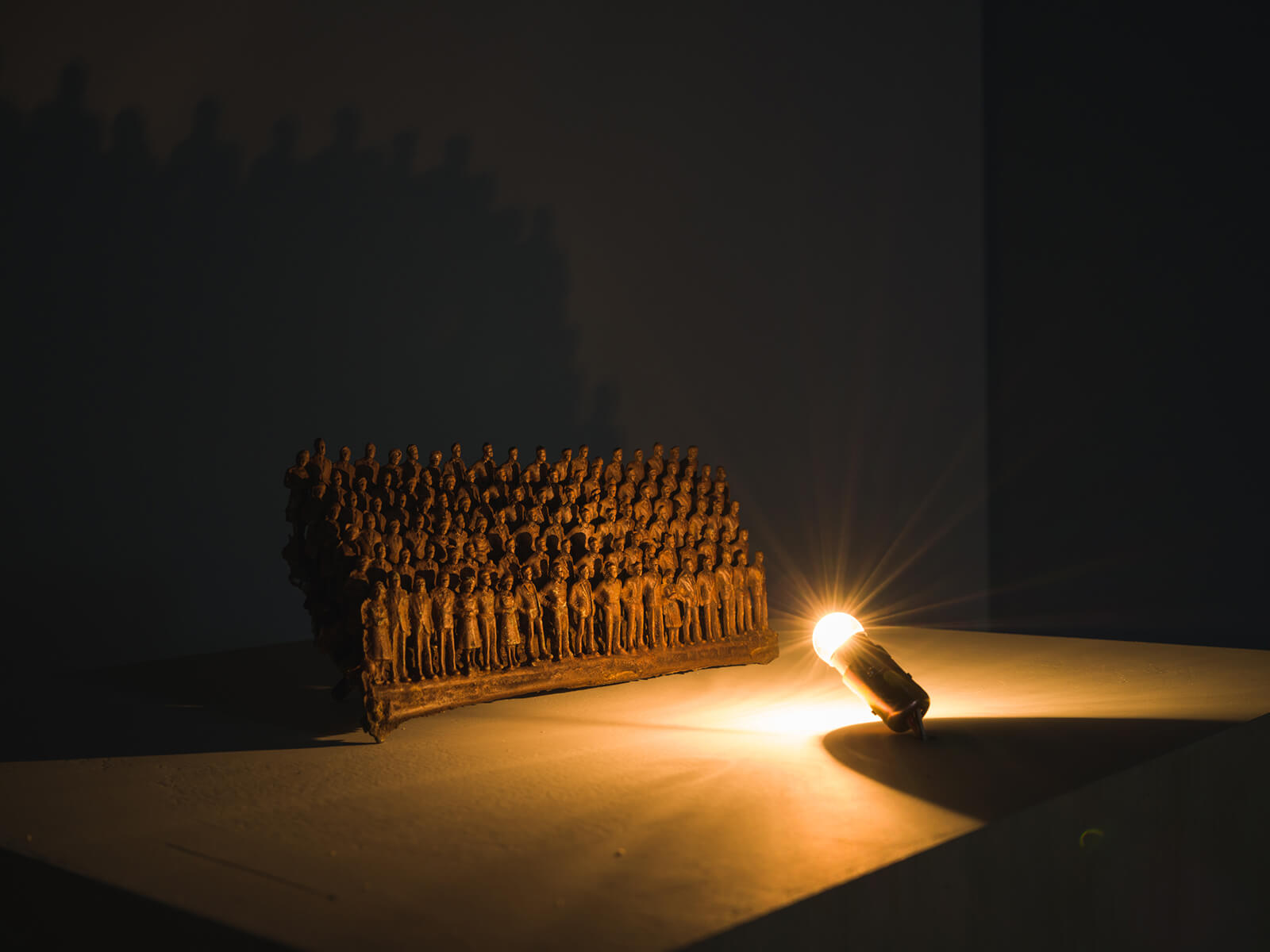

Nicolas: I confronted these two ideas, space and sound, and selected artists who address them in the light of climate change. Meanwhile, I found three sound patterns related to space. First, the feedback effect, also known as the Larsen effect, is created when two emitters are too close to one another. This strident noise comes from the lack of space for sound to diffuse normally. The second pattern is polyphony, which integrates different emitters as a collective movement and sound. The third pattern is the primordial sound, referring to the great outdoors, from the infinitely small, like the molecular, to the infinitely large, like the cosmos. These three sounds illustrate the dimensions of the exhibition, conceived like an opera and composed of artworks that serve as instruments or voices. Numerous artists are currently developing matching aesthetics.

Remy: How do you balance sound in such a visual opera?

Nicolas: Sound serves as a general metaphor for the whole exhibition, which will be an almost silent opera. However, some artists, like Hyewon Kwon, explore the relationship between space and sound. There will also be some sound pieces, such as Emeka Ogboh’s installation at the very beginning of the exhibition.

Remy: How will this show echo the specificities of Gwangju’s historical and cultural ecosystem?

Nicolas: I visited Gwangju for the first time in 2000 for the third Biennale and have developed a relationship with it over time. Gwangju is historically very important as the nucleus of democracy in South Korea and the Biennale was created to commemorate this fighting spirit. This important background is always present, but I didn't want to address it literally or directly because it has been done in the past. There will be a series of solo presentations in diverse venues, such as the neighbourhood of Yangnim, the cradle of Christian presence in the city. This neighbourhood is now defended by its inhabitants to resist gentrification. Saâdane Afif and Mira Mann will show their work there.

Remy: Since its 13th edition in 2021, the Gwangju Biennale has made space for national pavilions, similar to the Venice Biennale. What are your views on focusing on countries and national perspectives?

Nicolas: Those pavilions are not national as such. For example, it's not the state of Spain that pays for and organises the Spanish pavilion, but an entity from Spain, which is not exactly the official representation you find in Venice. Additionally, I try to have as much interaction as possible with these pavilions and their curators. For example, Julian Abraham “Togar”, who is in charge of the Indonesian pavilion, is also part of the main exhibition. Curators of pavilions also try to make their content coherent with the main exhibition.

Remy: What ultimately defines your curatorial approach?

Nicolas: My thoughts, my books, all my ideas come from the artists. However, curating, for me, is on another level where you have to transform the artists’ ideas into your own. If you don't do that, you become completely literal and just repeat what the artist has said. I try to engage with artworks more productively, introducing them to different meanings. If I install a work by Max [Hooper] Schneider next to a work by Dora Budor, it's not going to have the same meaning as if I installed it next to Julian Schnabel’s work. Those dialogues are constitutive of a group show, allowing it to go beyond the sum of its individual parts. This is the basis of curatorial grammar.

Remy: As for your art criticism, you pioneered the concept of relational aesthetics in the 1990s. Is relational art still a compelling framework for understanding artists’ work in the 21st century?

Nicolas: I started to re-evaluate the theory of relational aesthetics about 10 years ago for the Taipei Biennial. I remodelled it because my earlier approach was very anthropocentric, focusing solely on the human species. Over the last 25 years, we’ve come to understand that as a species, humans are not separate from nature but immersed within it. Therefore, I have developed an integral relational aesthetics, which now encompasses non-humans.

My thoughts, my books, all my ideas come from the artists. However, curating, for me, is on another level where you have to transform the artists’ ideas into your own. If you don't do that, you become completely literal and just repeat what the artist has said. – Nicolas Bourriaud

Remy: This concept has been more enthusiastically received in Asia than in Western countries, including your native France. How do you explain it?

Nicolas: This is an important point. Looking back at the origins of relational aesthetics, I think it was completely non-Western. The discussions I had at that time with Rirkrit Tiravanija and Surasi Kusolwong, among other Asian artists, were seminal. Prior to that, I spent a lot of time in India, including the entire month of August 1986 at the Thiksey Monastery in the region of Ladakh. I needed Asian thought to build my own. I needed that energy and alterity because I didn’t feel very comfortable in French culture. So, it's not surprising that this theory is still more discussed in Asia than in Europe. And I'm very proud of that.

Remy: Is relational aesthetics also a tool to re-assess museums as more interactive and less ethnocentric forums?

Nicolas: Museums can be many things. It really depends on the way you organise and activate them. There’s no fixed formula for them, but they reflect our way of revisiting the past. To me, it's all about storytelling. We need to keep inventing, much like the griot, an important figure in Africa who tells more or less the same story, but in different ways. That's what museums should learn to do.

Remy: Does this critical distance towards museums explain why you have worked more with temporary exhibitions like biennales than with traditional museums?

Nicolas: I would say that I haven’t been offered museum opportunities because I don't have a traditional approach. I would not necessarily refuse them; it’s just that they haven’t come up. When I was hired in Montpellier in the south of France, for example, it was to open a new space. What I did instead was transform an old space into a contemporary art centre and connect it to the art school. That's more my way of thinking: responding to the moment and the place. You can’t enter a situation and assume you already know what to do. It's a bit like feng shui: considering all the forces in presence, understanding the space and inventing new formulas, distinct from the classic ones.

Remy: Your book Postproduction offers another matrix for approaching contemporary art. But how do you look at it with the rise of AI and the metaverse, which were not part of your original corpus?

Nicolas: You point out a very interesting issue because Artificial Intelligence might be the only reason why I would add something to Postproduction. This book has been well received, serving as a link between the art and music worlds. But today, I would only add a new chapter or a foreword to discuss Artificial Intelligence and its implications. It would be about how algorithms are introducing the conclusive chapter for Hegel's theory of history, after [millenia] spent trying to negate its natural condition, human beings are now submitting themselves to a new master, mathematics.

Remy: What about The Radicant, your essay on the aesthetics of globalisation? As we now see a greater split in the world, have you noticed any shift in this matter?

Nicolas: My professional life started with the fall of the Berlin Wall. The 1990s marked the first time in centuries when walls were falling down. That was our happy globalisation, in a naive way. We didn't think about the economic standardisation of the world but focused on the possibilities that were opening up and blossoming at that time.

In the last 10 years, we've seen walls rising everywhere again. We are back in a Cold War-like situation, except that there's no other ideology than capitalism, which is even worse. We now suffer from people who believe they have a fixed identity that will never change. The Radicant, with its metaphor of a plant growing roots, while advancing, is even more valid today than 15 years ago. It illustrates that identities are not behind us but in front of us.

With its influential soft power, South Korea has become a highly relevant territory for reflecting on cultural globalisation. The theme of pansori, along with strong Korean representation featuring a dozen artists, promises a multilayered experience under Nicolas Bourriaud’s art direction. Following Taipei in 2014 and Istanbul in 2019, the new Biennale will conclude a decade of Bourriaud’s personal curatorial and aesthetic explorations.

Further solidifying Gwangju's position in the art world, the biennale will overlap with the Busan Biennale (August 17 - October 20, 2024), as well as Seoul’s busiest art week of the year, which includes the major fairs Frieze and Kiaf in the first week of September, and a series of shows opening in the capital, including Dream Screen (September 5 - December 29, 2024) at the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art, conceived by artistic director Rirkrit Tiravanija and curators Hyo Gyoung Jeon and Jiwon Yu.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Rémy Jarry | Published on : Aug 14, 2024

What do you think?