In ‘Bridge to Lanka’, experimental photographs reimagine a turbulent island

by Sonali BhagchandaniAug 17, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Rosalyn D`MelloPublished on : Dec 08, 2023

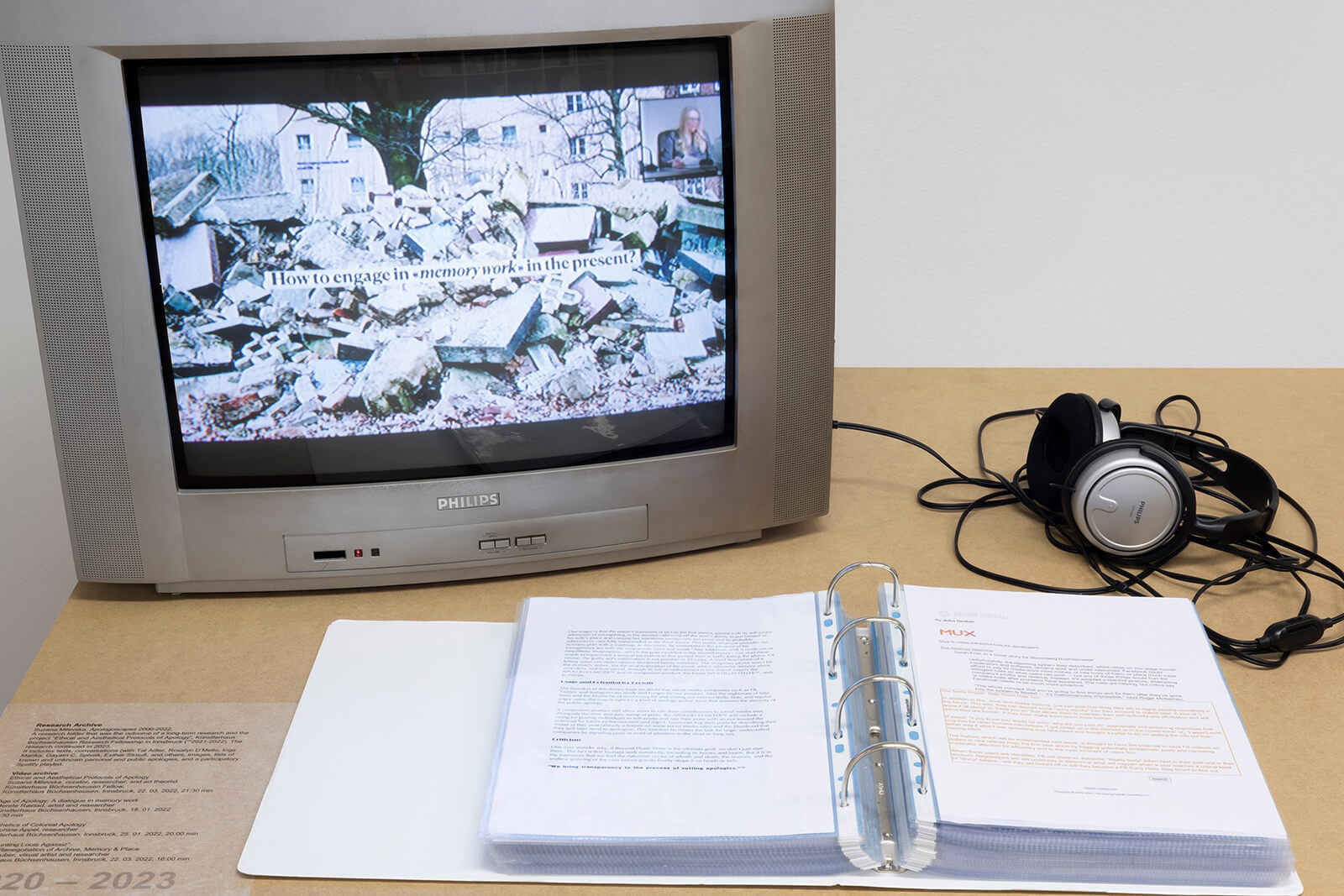

When I first encountered curator and theorist of art and visual culture Suzana Milevska’s research project on the ethics and aesthetics of apology, I was intellectually invested in its political-is-personal premise. Milevska, who hails from North Macedonia, was my peer at the Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen fellowship, Innsbruck, in 2021-2022. After our first meeting, I shared with her a feminist column I once wrote around 4:44, Jay Z’s musical apology to Beyonce for cheating on her and other misdemeanours. She invited me to dialogue with her on this subject which became one small unit within her research folder that grew significantly in size over the course of our fellowship period. My recent glimpse of this folder revealed a more substantial expansion. It was placed on a desk at the entrance to the art exhibition Sorry, the Hardest Word? at P74 Gallery in Ljubljana (November 7-30, 2023). The exhibition and parallel seminar are the first curatorial manifestations of her research.

Placed adjacent to a monitor relaying the four lectures that the exhibition curator hosted during the residency in Innsbruck, her research folder comprised several lists of public, personal and political apologies, theoretical texts, several of her written conversations (including the one with me and with artists Tal Adler and Esther Strauss, theorists Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and architecture theorist Inge Manka), anonymously filled forms by the participants of the workshop Is Sorry Enough? held in Innsbruck in the frame of her Fellowship and the participatory Spotify playlist Apologoscapes.

The show brings together powerful instances of the many ways in which a contemporary artist can intervene to advocate for missing apologies by long-term oppressors. It speaks not only to the violence that underlines situations in which the admission of harm is not acknowledged but also to the process of self-healing under trying circumstances. Especially considering the culture of impunity that has come to mark global politics, a clear consequence of the intersections between hetero-patriarchal systems, white racist supremacy and capitalism, the exhibition felt urgent, the themes and sub-themes almost crucial in terms of charting ways of moving forward from the morass of past oppressions. I asked the art curator to elaborate not only on her ongoing research but to dwell on how she arrived at the various artworks that inform the exhibition.

Rosalyn D’Mello: Could you briefly narrate the origins of your interest in the ethics and aesthetics of apology?

Suzana Milevska: My interest in the topic started even before the Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen Research Fellowship and exhibition. Particularly relevant for this show and the seminar were the series of exhibitions titled The Renaming Machine (2009-2011) that I curated for P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Institute and P74 Gallery, the conference I curated On Productive Shame, Reconciliation, and Agency at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna (2014) during my professorship in Central and South Eastern European Art Histories, and the exhibition Contentious Object/Ashamed Subjects that I curated in 2019 as the outcome of the project TRACES—Transmitting of Contentious Cultural Heritages with the Arts: from Intervention to Co-production. What all these projects have in common with Sorry, The Hardest Word? is my long-term interest in contentious memories, guilt, shame and reconciliation on the one hand, and on the other hand, how to move on from the traumatic past and agency necessary to rebuild our lives after tragedy.

I want to stress that apology as a topic was a starting point to investigate whether artistic practices can offer some relevant thoughts and means to ‘weigh in’ the ‘sorry’ word that stayed with me ever since I first saw the image of it written on the sky over Sydney’s Opera House during the National Apology Day in 2008, when the Australian Prime Minister apologised to the Indigenous children, the 'stolen generation whose lives had been blighted by past government policies of forced child removal and assimilations.'

More specifically, I was interested in the potentialities of different artistic research methods, aesthetical approaches and activist-turned strategies that created art projects aiming towards achieving social change and undoing different cases of injustice. In the past, I was invested in writing about some artists and artists who created their responses to various socio-political and cultural phenomena, and I wanted to pursue this interest in the context of apology as well.

Rosalyn: Could you talk about the political repercussions of your research?

Suzana: Unfortunately, the whole project turned out to be even more urgent than I could have ever anticipated. During the research phase I conducted in Innsbruck, the war in Ukraine added to its urgency. For example, among the participants in the workshop Is Sorry Enough? (Innsbruck, April 2022) were one curator and one artist from Ukraine who had just taken refuge in Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen.

Their answers to the main questions of the workshop’s form are in the [research] folder. Their answers are sincere, moving, and as poignant as possible, coming from young professionals who had just lost their homes and lives. In Ljubljana, some of the topics of the discussion, particularly in the seminar on November 8, 2023, at ZRC SAZU, dealt directly with the topic of genocide, which is relevant not only because of the current war between Israel and Hamas, and the ongoing atrocities, but also because of its relevance for the region during the wars in the ex-Yugoslavia. For example, the ethnic cleansing and genocide in Bosnia have still some unhealed wounds and traumas that continue to call for a proper apology—the one issued in 2003 never mentioned the term ‘genocide’. For me, it was also very important to discuss these issues in Slovenia because of the phenomenon of ‘Izbrisani’—the people who were erased from the registers after the conflicts and who lost their Slovenian citizenship only because they were not of Slovene origin (not necessarily refugees from the Balkan wars).

In various contexts, I mentioned that the one thing that is very important for an apology is to agree on the facts and to explain in detail the exact wrongdoings for which one apologises. In this respect, genocide is one of the hardest words for which one can apologise. Namely, there are all sorts of legal and political aspects and implications related to such an apology—admitting one’s own or a country’s engagement with genocide would necessarily bring a discussion about legal remedies such as restitution or reparations. Interestingly enough, King Charles avoided it during his visit to Kenya. I must admit that the current situation made me think and rethink the temporality of an apology. When and who should decide to issue an apology, whether there is the right time, and who decides that? It should be the victims, right?

However, it’s important to state that I came very far from only praising the apology. Unfortunately, apology often creates new hierarchies and harm while it tries to undo old ones. Several of the artworks on display in my show dealt exactly with the impossibility of an apology because although it is meant to be a bridge between the past and future, somehow this bridge becomes ‘the bridge too far’.

Rosalyn: Tell us about your first encounters with some of the works and artists in the show Sorry, the Hardest Word?

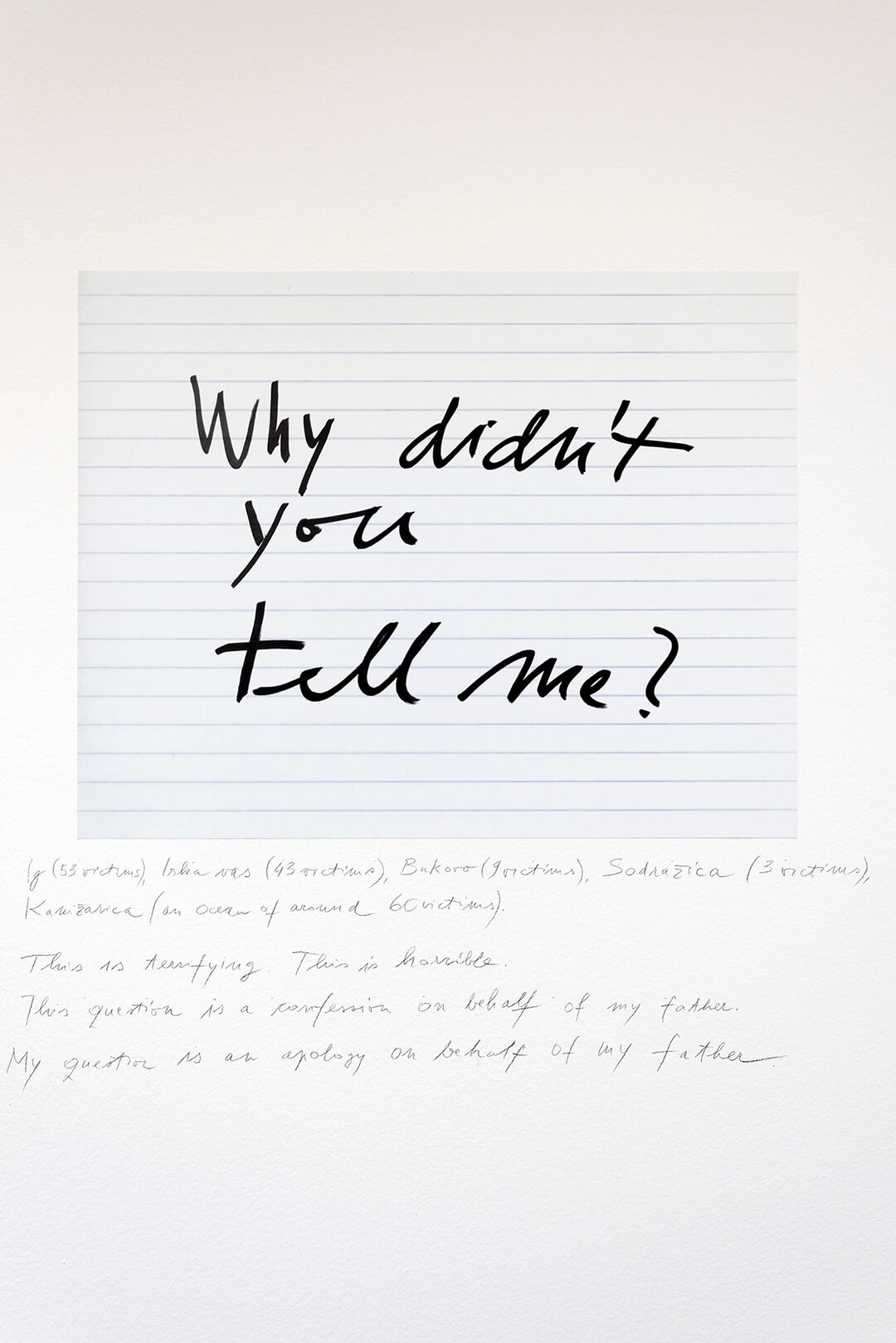

Suzana: I like to continue collaborating with certain artists who surprised me when I first became aware of their works, but I am always open to meeting new artists and getting acquainted with new artistic practices and aesthetics. For example, I first met Tadej Pogačar back in 2001, when he represented Slovenia at the Venice Biennial with his project I. World Congress of Sex Workers and New Parasitism. This was the first public manifestation of the CODE:RED project and one of the first participatory and research art projects that I encountered. I followed it with great interest, because it somehow motivated me to coin some specific theoretical concepts about which I’ve written in the past 20 years (for example, reversed recuperation: a strategy with which the artists use some funds and grants to empower small self-organised groups of various disenfranchised communities). My long-term collaboration with Tadej enabled me to initiate the research platform The Renaming Machine and research the complex phenomenon of renaming as one of the invisible socio-political mechanisms that affect our everyday lives in unexpected and everlasting ways. Tadej’s artworks never cease to surprise me, though. His work Why You Didn’t Tell me? is a very simple drawing-writing of the question from the title and excerpt from his new research about murdered Roma in Slovenia. What surprised me, and I guess many other visitors, is that the artist addresses this question to his late father—a member of the partisan movement, and apologises on behalf of his father for his long-kept secret—that, during the Second World War, besides the Fascist, the partisans also committed crimes against the Roma. When I asked the artist why he didn’t quote the sources of his information, he said the information was often publicised uncritically by the right-wing media and that there was a risk to give visibility to their platforms. This predicament somehow stresses the challenges of all of us researchers: how to deal with some unpleasant truths we come across during our research without legitimising the very same platforms that we want to criticise.

Through The Renaming Machine project, I also met Sasha Huber in Helsinki, during one of my first research trips. Her long-term engagement with the activist platform Demounting Louis Agassiz (DLA) and the artworks such as Rentyhorn and KARAKIA: The Resetting Ceremony were on my list several times because of Sasha’s long-term investment with renaming and un-naming as calls for decolonisation and other anti-racist initiatives. The DLA campaign, launched by the Swiss historian and political activist Hans Fässler, lobbied for renaming the peak Agassizhorn in the Swiss Alps because of Agassiz’s problematic past. Agassiz explicitly taught that enslaved Africans were innately and eternally inferior and advocated strict racial segregation, ethnic cleansing and government measures to prevent the birth of interracial children. He refused to accept evolutionary theory and believed blacks and whites had different origins. The main means and methods that he used to prove his scientific racist theories was photography (daguerreotypes). In 1850 Louis Agassiz had commissioned the daguerreotypes under the mantle of authority provided by his position at Harvard University.

The DLA campaign advocated renaming Agassizhorn as Rentyhorn in honor of Renty, the Congo-born slave whose photographs were at the center of Agassiz’s theory, and of those who met similar fates. As a DLA committee member, Huber’s activist and art engagements and aims were to raise awareness of the racial theories and the DLA campaign. She responded to the archival photographic material and collaborated with scientists, the implicated communities and the relatives of Renty. The campaign’s demands were brought and debated in front of the Swiss Parliament, with no successful renaming as its outcome, but the whole debate was widely publicised and discussed. Tamara Lanier, the great-great-great granddaughter of Renty Taylor started her research for more information on her relatives. She became aware of the existence of the daguerreotypes of Lanier’s ancestors that had been discovered back in 1976 by Elinor Reichlin, on staff at the Peabody Museum. In March 2019, 12 years after the start of the DLA campaign, Lanier filed a lawsuit against Harvard University and Peabody Museum (the trial is ongoing) for ‘wrongful seizure, possession and expropriation of photographic images’ of her enslaved ancestors.

In the show The Renaming Machine (and in Contentious Objects/ Ashamed Subjects) I exhibited the video that recorded Sasha Huber’s helicopter ride to the peak Agassiz and her ‘performance’ of symbolic renaming by putting a plate with an alternative name—Rentyhorn.

Sorry, the Hardest Word? includes Huber’s follow-up work Karakia—The Resetting Ceremony. It documents the ritual of a symbolic un-naming of a glacier in New Zealand which was also named after Agassiz. So, this example of an art project addresses the socio-political aspects of renaming in the context of racial injustice, colonisation and decolonisation and addresses the difficult questions about memory, identity, and name in such contexts. The artistic and activist ritual of un-naming unfortunately didn’t change the reality— that the glacier is still named after Agassiz—but it revealed the desiring machine of ‘accumulation by dispossession’ (David Harvey), through ‘taking’ symbolic and not only material things, such as the toponyms and names.

Finally, the latest encounters with Merete Røstad, Simona Schneider, Sam Richardson, Virgil B/G Taylor and Esther Strauss all took place in Innsbruck, on different occasions and capacities. Sam was also a research fellow and we shared the studio for several months. We come from completely different cultural, linguistic, professional, generational and lifestyle backgrounds. However, their project in Innsbruck—the one dedicated to the bearded saint Saint Wilgefortis, who came to be the patron saint of relief from tribulations somehow grew with me. Also, in Sam’s videos, I had a glimpse into their father's destiny. His involvement in the students' protests at Ohio’s Kent University—an event in which four unarmed students were killed with no repercussions for their killers somehow led me towards our further collaboration beyond our residency. The video 13 Seconds is a masterful narration about the traumatic effects of this case of state violence on Sam’s family and on their own artistic and personal struggles. In a way, I see Sam’s new work as an opportunity to shed some light on their previous work: the anti-institutional struggles present in the works about different renegades and protestors—given their family history.

I also want to mention Esther Strauss’ works, because perhaps her work confuses the visitors who don’t fully engage with them. She exhibits two works, one under her real name, and the other under the name Marie Blum which was also her ‘real’ name—for a year. Marie Blum was a real child, actually a Roma baby who was born and was killed in Auschwitz only three days after her birth. I met Esther just a week before I left Innsbruck, almost a year after Andre Siclodi, the Director of Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen, mentioned her and her work, knowing about my interest and investment in art and artists dealing with Roma issues, either Roma themselves or of other ethnic backgrounds. Esther exhibits her birth certificates as Esther Strauss and as Marie Blum and the certificates of the change. The reasons for this ‘performative monument’, as she dubbed her project, deals with her own contentious family background (her grandfather was an active member of the Nazi party) and the intertwining of microhistory and macrohistory. So, the works of Tadej, Esther, and Sam are different takes of the artists on their family histories, either apologising on behalf of their relatives, or calling for unconditional apology from the state (Sam’s work).

Tal Adler’s work deals with the contentious museum collections and unapologetic curators who, even during the interviews that are quoted in the video, cannot understand what’s wrong with collective remains. The work Who is ID 8470?, by Adler endeavoured to develop ways of rethinking the undocumented provenance of a skull held in the collection of the Institution Charité, Universitätsmedizin Berlin. His project Dead Images (2016) looked at the ethics of showing or not showing human remains in the Natural History Museum in Vienna in the context of the TRACES research project.

I met Adler in Vienna during my professorship in Central and Southeastern European Art History at the Academy of Fine Arts where he was engaged in a long-term research project that looked at the archives of different associations and collectives and collaborated with their members to reveal some contentious stories hidden in the archives. He developed his Dead Images project in the frame of TRACES that dealt with the same topic of Who Is ID 8470?— the provenance research of skulls and other human remains that are unquestionably collected and kept in many European museums even as we speak. The return and repatriation of such remains are the main motivation for his recent projects. His projects also deal with contentious memories, traumas, guilt, and shame, and he is on the quest towards finding artistic and aesthetical ‘protocols’ about how to move on.

An apology is just one, perhaps the first step on the rocky road towards forgiveness and reconciliation. There can be no apology that is a remedial ‘one size fits all’. But if the apology is not successful and not accepted by the ones to whom it’s directed, it’s very difficult to imagine moving forward, overcoming the troubles and difficult memories and traumas. The ‘sorry’ from the exhibition’s title is just a metaphor. I came across different ways of apologising, but the main issue is the promise not to repeat the wrongdoing and the determination to keep this promise. That is yet another difficult speech act. So, my real question that’s somehow implied, is ‘what comes after apology?’

Rosalyn: What are some of the other directions your research is taking?

Suzana: Right now, I’d prefer to put together different outcomes of my research, the exhibition and the seminar. I am in negotiations with the project’s partner institutions to try to fund an interdisciplinary publication that would comprise the artworks, the seminar’s presentations, and some relevant data found through this long-term research. I started the project with the assumption that an apology is a speech act and that there are differences between personal and collective apologies. The first assumption turned out to be wrong and I started disagreeing with most of the theorists because there were too many exceptions from the protocols of apology to expect it to be a successful speech act, in terms of JL Austin’s theory of speech acts.

The second assumption, the difference between personal and collective or political apologies also turned out to be vague: the example of the #MeToo movement proved that these two aspects are intertwined. There are many other aspects of apology that I’d like to discuss in such a publication, and there are also many artworks that I came across during the research that I could not invite for logistical or financial reasons and I could not embrace them in the show, so such a publication would be a challenging step forward.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

by Ranjana Dave Oct 03, 2025

Bridging a museum collection and contemporary works, curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath treat ‘yearning’ as a continuum in their plans for the 2025 Taipei Biennial.

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Rosalyn D`Mello | Published on : Dec 08, 2023

What do you think?