Herzog & de Meuron reframe the architecture of healing with a hospital in Zurich

by Mrinmayee BhootOct 18, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Bansari PaghdarPublished on : Jun 11, 2025

“We approach material not as passive matter, but as a carrier of time; compressed, displaced and often anonymised through industrial processes,” Swiss design practice Studio Eidola tells STIR. Founded in 2020 by industrial designer Denizay Apusoglu and architect Jonas Kissling, the studio operates at the intersection of architecture, design and material research. The practice identifies neglected residual materials such as mineral waste and industrial by-products, exploring their geological memory while proposing new frameworks for their application and meaning. On one hand, it explores the geology, ontology and production cycle of materials; on the other, it attempts to translate the material’s inherent and acquired complexities into visual, spatial and identical aspects of design.

Often beginning with a sculptural approach, the studio’s interventions eventually become enquiries of scale and circular systems, recontextualising waste materials into ingenious product designs. One of their early projects, Ocean Articulated (2021 – 22), examines layers of subterranean salt (remnants of the ocean) and glacial sand (deposited after the last ice age) in Northern Switzerland, through both a geological and temporal narrative. The project resulted in a series of forms of sand and salt, the collection comprising stools, tiles and pedestals that can dissolve either by introducing water or through natural decomposition.

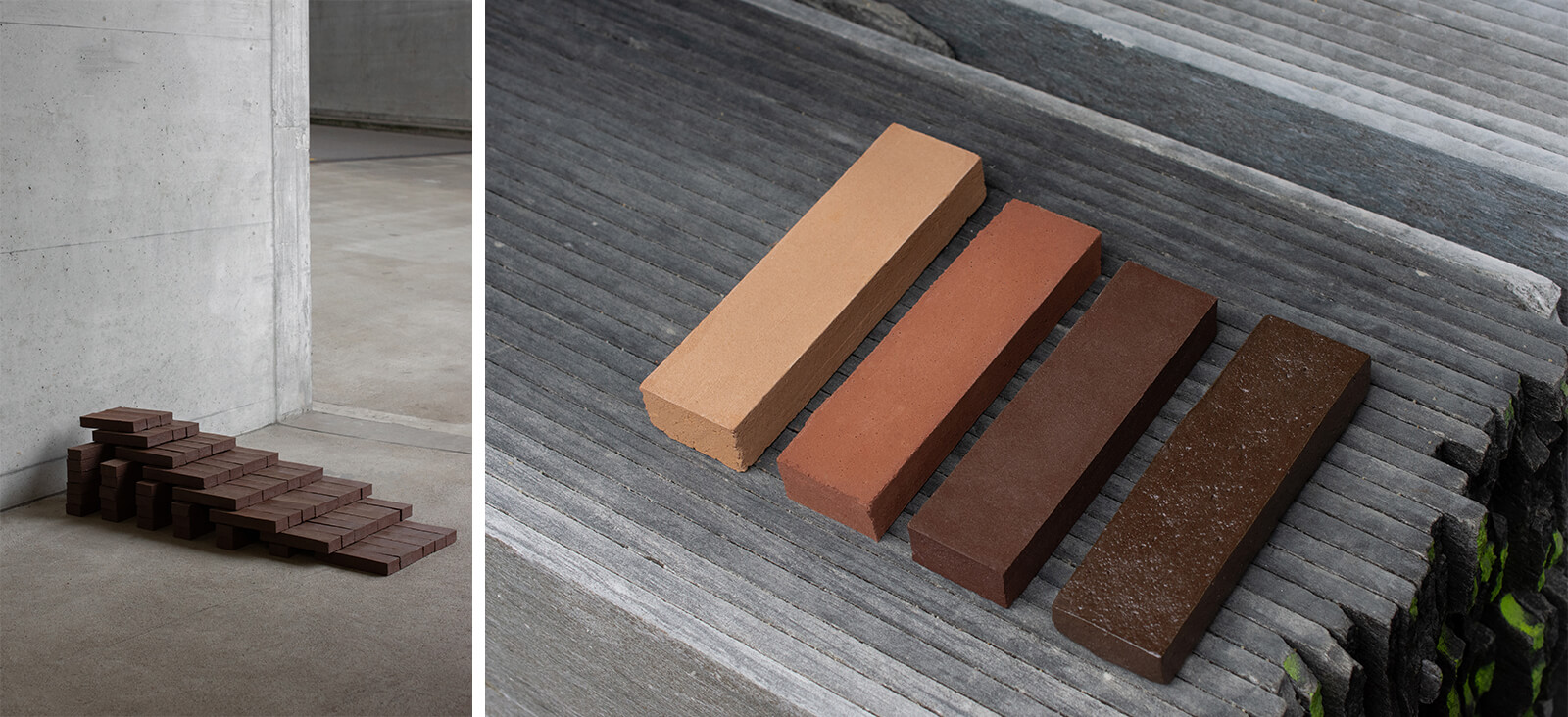

Another project, Fluid Residuum (2022), spotlights silt from the gravel quarries of Graubünden, drawing on ancient construction methods such as stone-masonry to shape sludge bricks. For Tectonic Dusts (2023), the studio focused on quartzite from the stone quarries of Vals, repurposing the dust from stone processing to craft bricks and tiles. Their latest project, Synthetic Geologies (2025), explores cement as a medium in flux, challenging its conventional use as a building material and shaping sculptures inspired by the lithification of sediments in nature.

Instead of hiding the imperfections of by-products, we try to keep their irregularities visible, so that they can reveal something about the systems that produced them. – Studio Eidola

STIR connects with Apusoglu and Kissling over an email interview to discover more about their creative process. The following are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Bansari Paghdar: Tell us about the inception of Studio Eidola, and what vision did you realise it with? How has the practice evolved over the years?

Denizay Apusoglu: We met at ETH Zürich, while Jonas was doing his master’s in architecture, and I was working in the prototyping lab within the same department, with a background in product design. What initially brought us together was a shared urgency: a curiosity toward the agency of materials, their latent histories and the ideological frameworks in which they are made to perform. Our collaboration began informally, through small experiments, and solidified in 2020 when we moved into a shared studio space, a kind of provisional commitment that nonetheless marked the beginning of a more intentional practice.

Jonas Kissling: From the beginning, Studio Eidola was conceived less as a conventional design office but as a platform for material inquiry. An investigative space concerned with site, substance and the overlooked residues of industrial processes. Our early focus was the High Rhine region in northern Switzerland.

Denizay: The exploration expanded into other extraction sites across Switzerland, and through conversations within the industry, we became increasingly aware of the immense volume of by-products generated by gravel/sand washing and stone manufacturing processes. Since then, our focus has shifted toward these industrial leftovers—materials that carry both spatial and aesthetic potential.

Bansari: How does a project take off, and what stakeholders are usually involved? Where do the products of the interventions end up?

Denizay, Jonas: Each project emerges from a site, but more precisely from an encounter: with a quarry, a processing plant, a stockpile of discarded aggregate. We initiate these dialogues ourselves, often with plant managers or company owners, not to secure a resource but to understand its condition—how it got produced in excess, what logistical or regulatory mechanisms rendered it obsolete and what imaginaries might be constructed around it. The process unfolds through repeated visits, informal exchanges and the slow accumulation of the context.

At present, design exhibitions remain our primary platform for making the work public. We also engage through lectures and panel discussions to share findings and situate our work within broader ecological and material discourses.

Bansari: Your interventions are deeply site-specific and entail extensive research on materials and geographies. Could you walk us through the overarching process of a project?

Denizay, Jonas: While the initial stages of each project begin with site visits and conversations, what follows is the collection of material samples directly from the site. Back in our studio in Zürich, these fragments are subjected to hands-on investigation, intuitive manipulation, and, at times, lab-based analysis to uncover their composition and behaviour. This phase is deliberately open-ended, and we resist pre-determined outcomes.

Bansari: While a large part of your work dwells in quarrying processes, is there a typology of a waste site within or outside of Zürich that you are particularly keen to investigate?

Denizay, Jonas: We are currently expanding our mineral by-products map of Switzerland, and this involves an ongoing engagement with diverse extraction and production sites across the country. While our focus has so far centred on gravel pits and stone quarries, our recent solo exhibition (Synthetic Geologies) in Vienna has opened a new line of inquiry into cement production. Despite its industrial efficiency, the cement-making process generates its own peripheral flows and residues. We are particularly interested in these less-visible waste streams.

We hope to challenge the common idea that refinement means hiding all traces of a material’s past. – Studio Eidola

Bansari: In your opinion, how has the construction industry's approach and outlook on overlooked materials and circular production evolved over recent years? In this context, what is Studio Eidola's contribution to challenging how such materials are perceived?

Denizay, Jonas: In recent years, the construction industry in Switzerland and Europe has begun to acknowledge the limits of its extractive logic, prompted in part by regulatory shifts, resource scarcity, and environmental pressures. Terms such as circular economy and material reuse have entered the mainstream, yet often remain framed within efficiency-driven narratives, focusing more on minimising waste than rethinking material ontology. Overlooked materials are often reclaimed through processes that erase their origins, making them recognisable only when they align with established norms of efficiency and uniformity.

What remains largely unaddressed is the cultural and temporal dimension of these materials: their embeddedness in landscapes, labour systems and geological memory. We operate in this space of ambiguity, where material is not yet a product, and waste has not yet been rendered functional. Instead of hiding the imperfections of by-products, we try to keep their irregularities visible, so that they can reveal something about the systems that produced them. Our contribution is in resisting the urge to clean up or standardise leftover materials, and instead offering a slower, more context-sensitive way of working with them. We aim to shift perception not only by encouraging a renewed sensitivity to what is often dismissed or hidden, but also by demonstrating that these overlooked materials possess qualities worthy of being reintegrated into systems of value and use.

Bansari: The aesthetics of your designs embody their industrial origin and production, becoming one of the essential aspects of generating discourse on the subject. What are your views on this?

Denizay, Jonas: We see aesthetics as a critical site of negotiation, where the material’s origin, its industrial trajectory and its exclusion from dominant systems of value can be made visible. We intentionally aim to retain traces of extraction, processing and displacement; they operate as narrative devices, allowing the material to speak of its own making and unmaking. In doing so, we hope to challenge the common idea that refinement means hiding all traces of a material’s past. The aesthetic, in this sense, becomes a tool for unsettling assumptions around material purity and utility.

Bansari: Operating on the threshold of ambiguity, uncertainty and a constant state of in-between, what do you find the most liberating and challenging aspect of your practice?

Denizay, Jonas: What feels most liberating is precisely the refusal to settle into fixed categories of discipline, function or outcome. Uncertainty becomes a site of potential rather than a problem to solve, which grants us the freedom to remain responsive.

One of the most challenging aspects of our practice is that what we create often doesn’t fit into established categories or expectations, which makes it difficult for others to immediately understand or place. It requires a level of attention and interpretation that cannot be assumed, which can create a sense of friction when navigating institutional or public contexts that are used to clearer definitions and outcomes.

Bansari: What is NEXT for Studio Eidola?

Denizay, Jonas: We are preparing for a design residency in Cairo towards the end of the year, where we will extend our research into the mineral landscapes of Egypt, both in their deep historical layers and contemporary industrial contexts. Simultaneously, we are in the early stages of establishing a raw-material supply company in collaboration with an industrial partner. It is a significant step in scaling our practice, aiming to bring overlooked by-products into architectural and industrial circulation while offering support in developing material strategies rooted in specificity rather than standardisation.

Treating the landscapes of Switzerland as sites of material enquiry, Studio Eidola challenges how one looks at by-products. Instead of erasing traces of their origin and memory, the practice highlights their story and often translates it into the aesthetics of the final product. With some recent research projects, the practice expands its horizons beyond Switzerland, towards Fátima in Portugal and Kota, Makrana, Jodhpur and Jaisalmer in India. For an upcoming project in Egypt, Studio Eidola explores the architecture of Siwa and Cairo, unfolding the regional material narratives. “We aim to immerse ourselves in millennia-old building methods, dedicating substantial time to grasp the intricacies of material extraction sites, transportation networks and their cultural ramifications,” the studio tells STIR. Working at the confluence of geography and historical and contemporary building narratives, the studio contributes to the discourse on post-contemporary material culture and provides a nuanced perspective on ‘contextually resonant design’.

by Chahna Tank Oct 15, 2025

Dutch ecological artist-designer and founder of Woven Studio speaks to STIR about the perceived impact of his work in an age of environmental crises and climate change.

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 14, 2025

In his solo show, the American artist and designer showcases handcrafted furniture, lighting and products made from salvaged leather, beeswax and sheepskin.

by Aarthi Mohan Oct 13, 2025

The edition—spotlighting the theme Past. Present. Possible.—hopes to turn the city into a living canvas for collaboration, discovery and reflection.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 11, 2025

The Italian design studio shares insights into their hybrid gallery-workshop, their fascination with fibreglass and the ritualistic forms of their objects.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Bansari Paghdar | Published on : Jun 11, 2025

What do you think?