UnBroken at Camden Inspire 2025 proffered salvaged stories and second lives in design

by Asmita SinghOct 04, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Jincy IypePublished on : Jun 13, 2025

Last month, a new kind of museum storehouse opened doors within the East Bank cultural quarter in London, UK: the V&A East Storehouse. Tucked inside the cavernous Here East site—once a media centre of the London 2012 Olympics—this vast 16,000-square-metre space, spanning four levels, challenges the notion of how art and artefacts are shown, seen and stored within a museum space. It’s a warehouse, a backstage pass, a living workshop and a ‘radical’ experiment in democratising access to the national collections on display, open for witnessing, interpretation and scrutiny. The storehouse, with its sentient, industrial aesthetic, is a ‘new purpose-built home’ for over 250,000 objects, 350,000 books and 1,000 archives, which forgo the typical glass casings and dark crevices for the company of crates, ladders, shelving and working forklifts.

“A world-first in size, scale and ambition and [a] new source of inspiration for all, V&A East Storehouse immerses visitors in over half a million works spanning every creative discipline from fashion to theatre, streetwear to sculpture, design icons to pop pioneers. A busy and dynamic working museum store with an extensive self-guided experience, visitors can now get up close to their national collections on a scale and in ways not possible before,” mentions V&A in an official statement.

At the heart of this venture lies a principle both simple and profound: to lay bare the heterogeneity of the V&A’s collections. Elizabeth Diller, founding partner of New York-based design studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), which designed the project, recalls in conversation with STIR, “We were given Here East as the starting point and the collection that was moving from Blythe House. The ground zero idea was the heterogeneity of this vast and eclectic collection, with varying artefacts, media, scales and materials from different eras and points of the world.” There was no attempt to polish or distil this diversity into a singular narrative. Instead, Diller says, “We imagined filling the space with artefacts—wall to wall, floor to ceiling—then coring out the middle like a geological core, creating an immersive cabinet of curiosities that invites people to wander and wonder.”

Here, the aesthetics, ethos and programme is all one thing—no distinction. – Elizabeth Diller, founding partner, Diller Scofidio + Renfro

In the Weston Collections Hall, the result is brave, a three-dimensional puzzle that evokes both order and surprise. What anchors this hall are architectural remnants themselves which include an exquisite 15th century carved and gilded wooden ceiling from the now lost Torrijos Palace near Toledo in Spain, a full-scale Frankfurt Kitchen designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, and the 17th century Agra Colonnade from the bathhouse at the fort of Agra in India. Interestingly, the largest Picasso work in the world – the rarely displayed stage cloth from the Ballets Russes' Le Train Bleu also takes its own spotlight, standing over 10 metres high and 11 metres wide.

The Hall hums with the echo of centuries and the immediacy of discovery, as these objects are brought together with a series of co-production projects in collaboration with young East Londoners, communities and creatives. It also includes ancient Buddhist sculptures, PJ Harvey’s guitar, costumes worn by Vivien Leigh, items from the Glastonbury Music Festival, Suffragette scarves, Thomas Heatherwick’s model for the London 2012 Olympic Cauldron and more, where visitors lead their own path through the 100+, frequently changing mini curated displays, which as per the museum, have been ‘hacked into the ends and sides of the storage racking’.

Tim Reeve, deputy director and COO of the V&A, who developed the V&A East Storehouse concept, sees this as a departure from the traditional museum’s polished formality. “This is a working building and a public experience,” he says. “We wanted to create a genuine public building, where visitors feel welcome, where they can sense that this place was made for them, not to be revered from a distance.” It’s a museum design that doesn’t seem to stand on ceremony—its steel frame warehouse shell speaks to those who might feel odd among marble columns and mosaic floors. Here, according to Diller, the aesthetics, ethos and programme are all one thing—no distinction.

This sense of immersion and informality is no accident, as Diller shares in the interview. “It’s a functioning storage facility. The artefacts are on pallets, moved around by forklifts, displayed in this indigenous home that’s raw and unvarnished. There’s a sense of illicitness, of going behind the scenes to places you’re not normally invited,” she notes.

David Allin, principal at DS+R and the project’s architect for the last seven years, reflects on this paradox of openness and privacy. “The magic of Blythe House was seeing objects stored for the logic of the collection, not curated for the public. We wanted to hold onto that authenticity while making it accessible.”

“Conceptually,” he adds, “the smallest piece of jewellery and these monumental architectural remnants are all objects, all worthy of the same scrutiny.” Each artefact, in the way it is organised and presented, is both autonomous and part of a larger whole, like the Storehouse itself.

The project gives the public access to the new V&A’s working storage facility. From the unassuming entrance to the modest entrance lobby at the street level, visitors access the walkway which traverses through racks of storage before entering the dramatic clearing in the centre of the dense warehouse, the 20-m high Weston Collections Hall. The hall here seems to stretch indefinitely in multiple directions, even below, through a section of glass floor. “The objective was to create a sublime feeling of the vastness of the collection and, at the same time, a sense of illicit trespass into a space normally unavailable to public view,” notes the press statement.

This Hall remains bounded by ‘concentric layers of accessibility’ where the innermost layer reveals open crates to the public; the middle is a semi-public archive; and the outermost one houses private spaces for museum staff, conservation work research and deep storage, where objects remain protected from excessive light, dust or human contact. “Effectively, the typical institutional building is turned inside-out, with the most public space located farthest from the front door and the most private on the outer edge. Small pockets of space are reserved for back-of-house uses and public functions," explains the release.

We want to show the full working of the V&A, everything that goes on behind the scenes. In that sense, it is both a working building and a public experience. – Tim Reeve, deputy director and COO, V&A

According to the architects, this is adaptive reuse at its most radical sense, or at least, was approached as such. The Storehouse doesn’t shy away from its industrial roots, as it celebrates them and puts them front and centre. As Allin shares with STIR, “There’s a kind of funny irony in the fact that the most visible part of the whole V&A space is the mechanical equipment, the life support system that makes the climate work.” The building’s voice is confident. Its refusal to compete with the grandeur of a typical museum’s intimidating façade and conventional megalomania lets the objects on display themselves speak, directly, to the public. A fresh take on museum storage.

Crucially, the V&A Storehouse embraces co-production and transparency, acknowledging that every object carries layered, sometimes disputed histories (read: the colonial nature of the objects on display). “We’re laying everything bare,” Reeve asserts. “Nothing is hidden. It’s not about the V&A’s curated narrative—it’s about what these objects mean to others, to their communities.” From the unique ‘Order an Object’ service, where visitors can select objects for intimate viewing, to the co-produced displays, the Storehouse invites everyone to become a curator of their experience.

"Instead of the hard distinctions between storage and display, conservation and curation, back-of-house and front-of-house, V&A East Storehouse creates a new mixture,” shares Allin. “To realise the project, everyone had to step out of their comfort zone: curators became storage experts, technical services staff acted as exhibition designers and we, as architects, learned to be collection managers. This experiment continues, with the public now asked to invent their way of exploring the V&A's collection of remarkable things.”

What emerges from this quietly radical project is a balancing act: a delicate one between exposure and protection, the public and the private, the custodial and generous. In the words of Diller, “It’s about exposing the workings of something—its rawness—and allowing for interpretation. It’s about giving the public agency, to move freely and make their connections.” Here, the industrial architecture is not a shell to be filled but an integral part of the experience: its utilitarian lines become a canvas for the heterogeneity hosted within.

The craftsmanship and care present behind the scenes of the warehouse is now visible to the public, and that’s want we wanted to capture. – David Allin, principal, Diller Scofidio + Renfro

The V&A East Storehouse is already being received as a fresh, inclusive cultural model—one that resonates with the energy and spirit of East Bank (the new cultural quarter in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park supported by the Mayor of London), itself a new creative and educational district shaped by the city’s layered histories and evolving communities. The Storehouse is permeable by design—both physically, with glimpses into its bustling storage and workings and conceptually, as a space where the institutional becomes communal. It’s a place where the craftsmanship and care once hidden behind the scenes are now intentionally made visible to all. A place where history is not locked away in darkness, within obscurity or elitist pockets, but shared, out in the open—generous, democratic and in perpetual dialogue with those who come to find their own meaning within its walls.

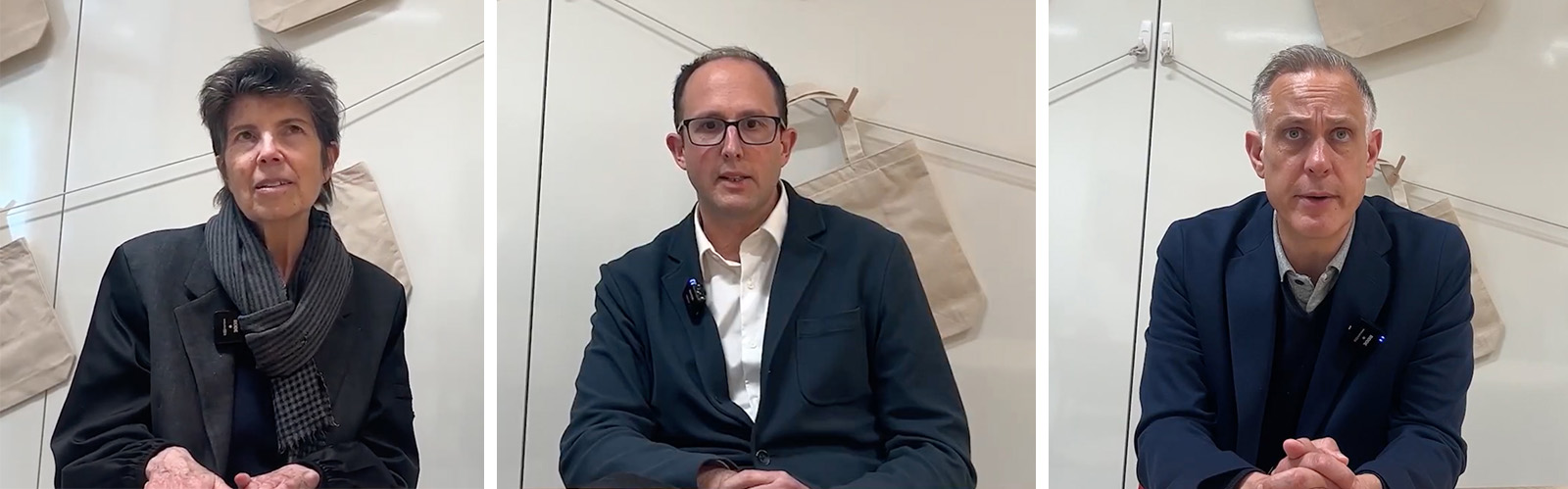

Tap on the cover video to watch STIR's full conversation with Elizabeth Diller, David Allin and Tim Reeve.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Jincy Iype | Published on : Jun 13, 2025

What do you think?