Bharti Kher presents a transformative body of work at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

by Rajesh PunjSep 06, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Hili PerlsonPublished on : Aug 26, 2024

It’s not until visitors reach one of the exhibition’s final galleries that they encounter the most emblematic work in Do Not Abandon Me, a survey of Louise Bourgeois’ oeuvre curated by Philip Larratt-Smith and Sergio Risaliti in collaboration with The Easton Foundation at Florence’s Museo Novecento. Placed in a corner, on the museum’s black stone floor, is a medium-sized sculpture of a spider — a central motif in Bourgeois’ work and certainly her most recognisable. But this sculpture, titled Spider just like all other pieces of the same shape, includes a white marble oval—a spider’s egg sac—which it appears to be protecting with its divaricate metal body. Created in 2000, it is the only spider sculpture Bourgeois has ever produced that includes an egg. What’s more, the work is held in a private collection and has never been publicly exhibited before. It is a splendid rarity and at the same time, a sobering clarification: all those Louise Bourgeois spiders installed at some of the most prestigious art spots all over the world are in fact without offspring, the absence of a smooth stone oval between their jagged metal legs suddenly becoming too striking to unsee.

This summer, Italy is playing host to two major museum exhibitions dedicated to Louise Bourgeois, in Rome and Florence, each curated with a different focus. Both have been planned for years and organised in collaboration with the Easton Foundation, which Bourgeois set up to manage her estate. In the Italian capital, a survey of Bourgeois’ sculptural works is installed within the spectacular interiors and singular collection of the Galleria Borghese and explores the artist’s work with found materials, textile, metal and marble in the context of her biography. Meanwhile, here in Florence, the exhibition brings together nearly 100 artworks created between 1995 and 2000 and highlights the ways in which Bourgeois thought about the cycles of life through her work and about womanhood and motherhood, in particular. The pregnant female body, childbearing and breastfeeding are depicted unambiguously and sincerely in many of the pieces on view, ranging from soft and filigree textile sculptures to marble and iron pieces, drawings and gouaches on paper and a cell. The colour red dominates the wall works in the show, while several sculptures are mostly awash in fleshy pinks and tans. Heartbreak, it seems, is tenuously woven into every image and object.

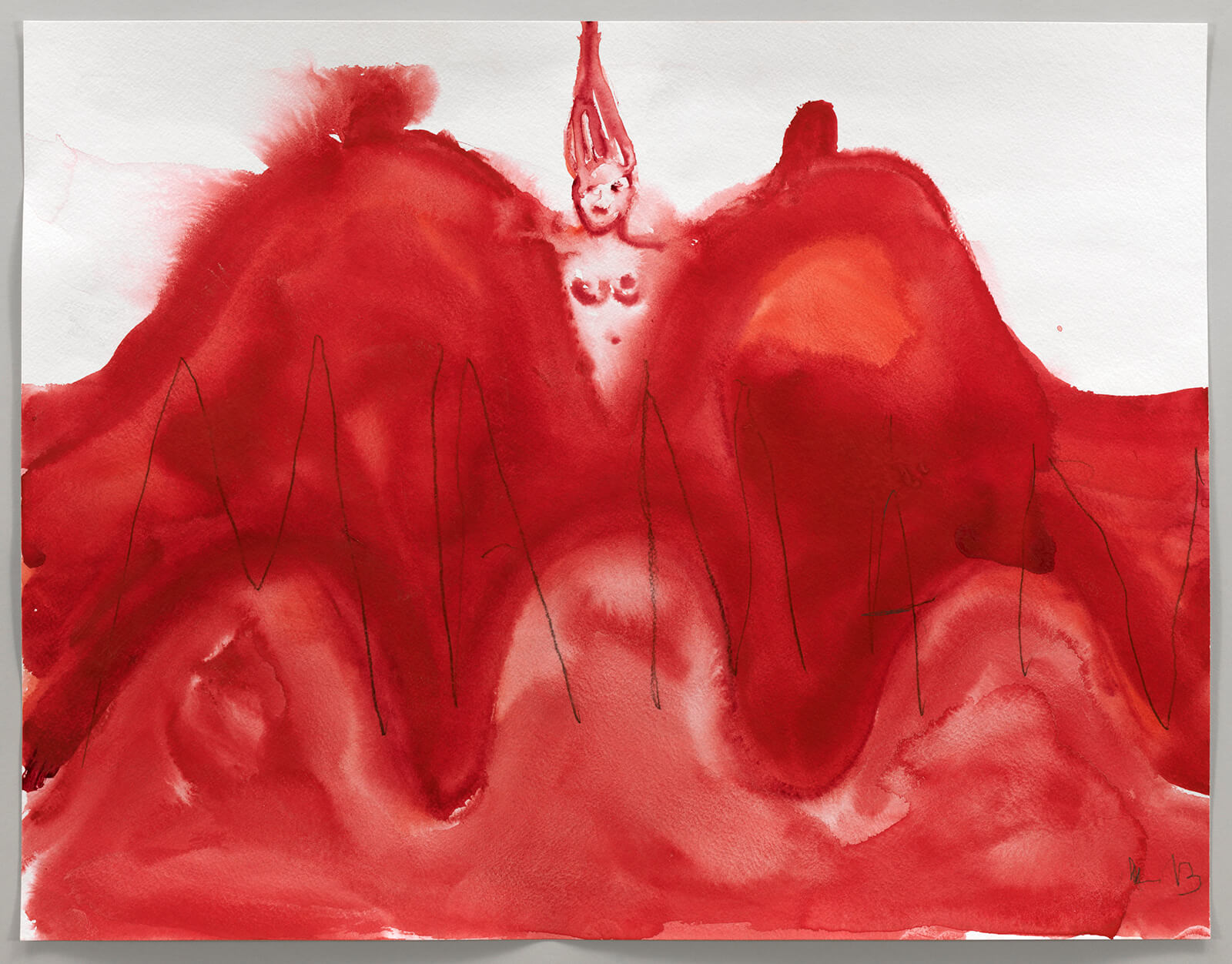

Bourgeois’ red gouache works on paper, created in the last five years of her life (born in France in 1911, the artist passed away in 2010, in New York) are presented across several galleries and form the core of the survey. These works evince her near-compulsive return to the theme of motherhood and the inevitable abandonment, or the series of abandonments, that the fact of childrearing entails. The cutting of the umbilical cord, for example, symbolises the swift ending of the mother-child dyad, rather than a new life. Bourgeois’ mother passed away when she was 21 years old and the trauma of this abandonment figures in much of her work. “You need a mother. I understand, but I refuse to be your mother because I need a mother myself,” reads a quote by Bourgeois that the museum included in the exhibition notes, yet unfortunately without additional context. She painted using a “wet on wet” technique, in which her marks dissolved quickly and ran across the paper, which requires from the artist both trained expertise and the ability to relinquish some control over the process. This tension between controlling and letting go seems to have had therapeutic value.

The presentation of the works in the show engages cleverly with the museum’s architecture and history. Originally built in the 13th century as a hospital, it was run by female communities of nurses and nuns. In the small, high-ceilinged space that used to serve as a chapel, the bronze and silver sculpture Cross is installed where the chapel’s original cross once stood, appearing as if it has always belonged there. It shows outstretched arms holding two additional pairs of arms holding hands, cast from the artist’s own body. Nearby, a rectangular hunk of pink marble sits on the floor. Titled Nature Study # 5 (1995), the sculpture is carved on the interior to show a cascade of full, round breasts, appearing inviting, soft and warm to the touch, despite their materiality.

On the upper level, the suite Do Not Abandon Me, (2009-10), which Bourgeois created in collaboration with British artist Tracey Emin, is hung amidst other wall works by Bourgeois. Lending its title to the show, the series is presented here with 16 digital prints on fabric. To produce this artistic dialogue, Bourgeois, nearing the end of her life, would send runny red and blue gouaches of male and female torsos to Emin, who added her narratives and details, performed in scraggly drawings and texts around the figures. In hindsight, considering that Bourgeois would pass away shortly after these were created, this shared process could be read as one artist’s farewell to a spiritual mother who’s about to leave. Concluding the tour through the museum, the towering bronze sculpture Spider Couple (2003) stands in the middle of the Renaissance courtyard of what used to be the cloister. Another rarity is Bourgeois’ only spider sculpture that represents a couple and could refer to a husband and wife, father and mother, or mother and child. It could represent protection, an embrace, or domination and suffocating control. “All my work is suggestive; it is not explicit,” Bourgeois is quoted in the exhibition’s notes. “Explicit things are not interesting because they are too cut and dried and without mystery.”

To produce this artistic dialogue, Bourgeois, nearing the end of her life, would send runny red and blue gouaches of male and female torsos to Emin, who added her narratives and details, performed in scraggly drawings and texts around the figures.

But the exhibition includes one more work, installed offsite in a partner institution, the Museo degli Innocenti. A short walk across the busy streets of Florence’s touristic centre, the charming museum is located inside a Renaissance-era orphanage. Bourgeois’ Cell XVIII (Portrait), (2000) is installed amidst some of the collection's most iconic works. The cell features a pink textile bust clad in a cape of the same fabric. It is bowing its head towards an opening in the front of the pleated cape, out of which several blue, white and black fabric heads pour out. Its protection suffices for all of them, at least for now.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

by Hili Perlson Sep 26, 2025

The exhibition at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus unpacks the politics of taste and social memory embedded in the architecture of the former East Germany.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 25, 2025

At one of the closing ~multilog(ue) sessions, panellists from diverse disciplines discussed modes of resistance to imposed spatial hierarchies.

by Mercedes Ezquiaga Sep 23, 2025

Curated by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, the Bienal in Brazil gathers 120 artists exploring migration, community and what it means to “be human”.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Hili Perlson | Published on : Aug 26, 2024

What do you think?