MAD Architects envisions a luminous ‘cloud’ for Cloud 9 Sports Center in China

by STIRworldMay 14, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Dhwani ShanghviPublished on : Apr 16, 2025

Snow and ice tourism, once concentrated in the northern parts of China, is now gaining traction in the traditionally warmer southern and central regions, including Jiangxi, Hubei and Hunan, as people increasingly seek winter experiences closer home, especially in conventionally warmer cities. Fuelled by social media and residual fervour from the Beijing Winter Olympics 2022, destinations previously unfamiliar with (or unsuited to) winter tourism have witnessed a surge in visitors in the pursuit of these experiences—a hedonistic escape—increasingly at odds with environmental realities.

Wuhan, once branded one of China’s “four furnaces”—a term referring to the country's hottest cities—and the capital of the traditionally warm Hubei province, is now positioning itself as a new frontier for year-round winter tourism. In 2024, the province recorded a nearly two-fold increase in visits during the winter holiday compared to the previous year, with Wuhan as one of the few southern routes in the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s national ice and snow tourism list. Against this uncanny backdrop, the Wuhan Ski Resort emerges as a bold piece of sports architecture, bringing an immersive winter world into a subtropical environment.

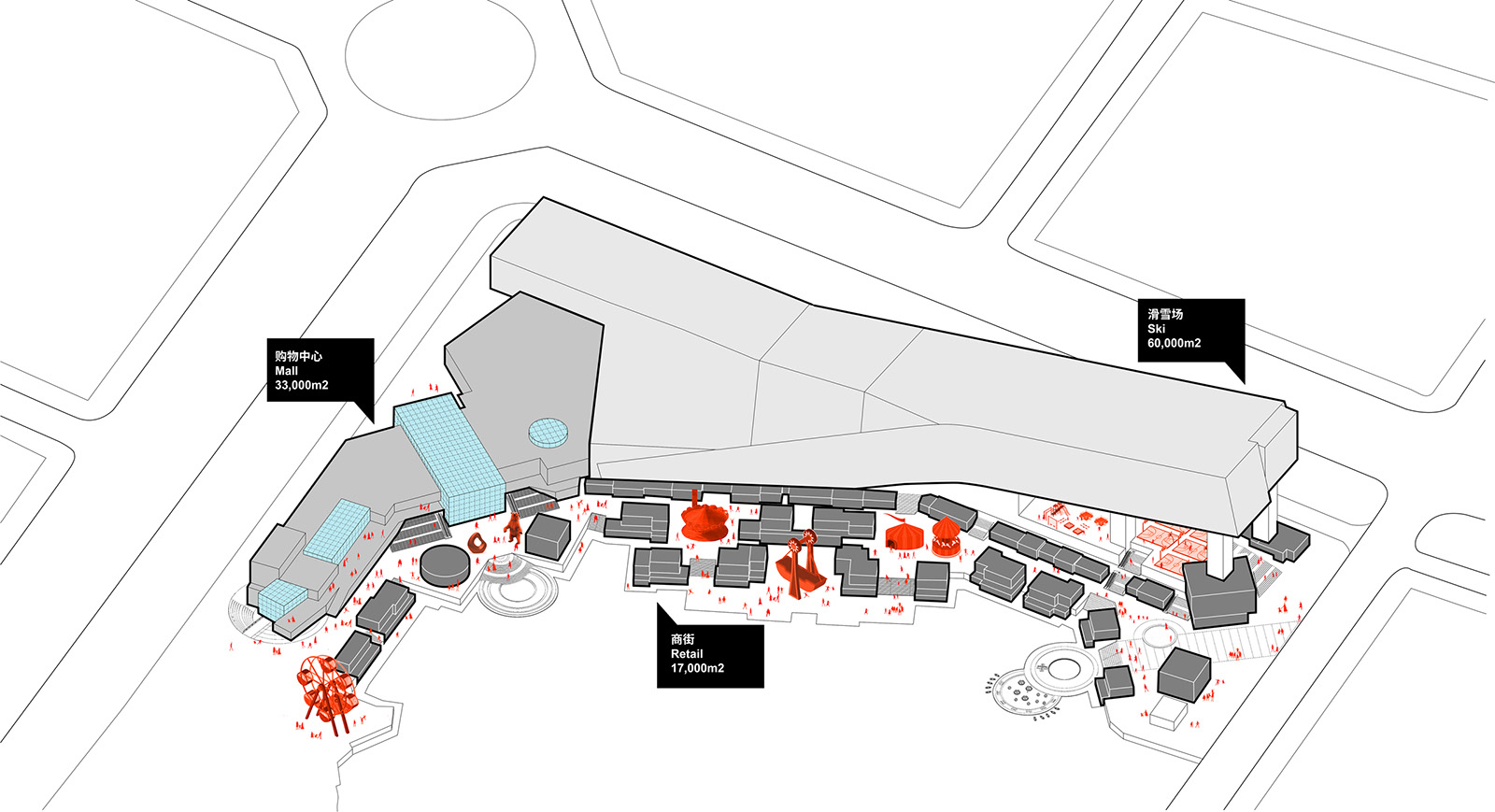

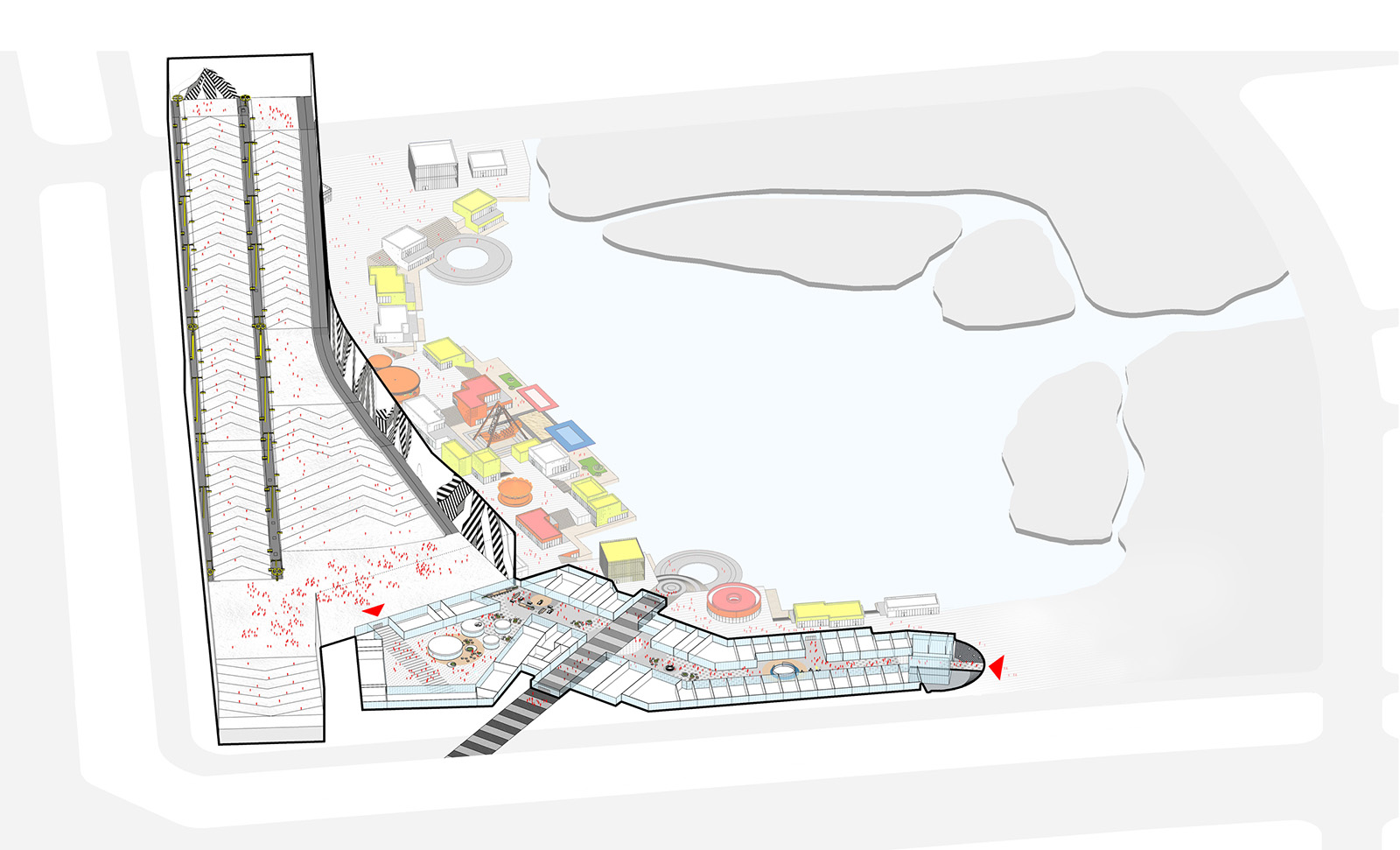

Designed by Beijing-based CLOU Architects, the expansive urban intervention is part of the 178,000 sq.m. Wuhan Ganlushan Cultural and Creative City, an expansive ice and snow-themed park located in the city’s Huangpi district, adjacent to the historic Mulan Ancient Town. The development is dominated by a monumental, sloping rectangular mass that rises to 100 metres, enclosing a 60,000 sq.m indoor ski slope with six trails ranging from 110 to 260 metres in length, along with a vertical drop of 73 metres. The Chinese architects wrapped the façade in a pixelated modular screen—an animated geometric grid that suggests movement while concealing the technical infrastructure behind.

At its base, the site opens into a central lake surrounded by a lively mix of indoor and outdoor programmes, including sports venues, landscaped plazas, retail streets and waterside promenades that can remain active throughout the year. These elements of recreational architecture are housed within a cluster of colourful volumes that echo the playful geometry of Lego blocks.

In contrast to the grid of the ski slope’s façade, the ensemble further introduces a modular design language of its own—tactile, varied and human-scaled—forming a dynamic civic edge to the towering mass above. With additional offerings such as hotels, shops, theme parks and other amenities, the commercial architecture resembles a mountain with a rural outpost at its base, forming an integrated ecosystem where people can live, work, play, train and unwind.

The modular, pixelated façade that clads the half-kilometre-long ski slope layers graphic motifs and LED lighting with shifting depths to create a visually dynamic facade design. Conceived as a unifying skin for the complex programme within, it balances cohesion with spectacle. Yet, for all its visual strikingness and ambition, the pixel logic and lighting design lend the building a high-tech sheen that doubles back on the structure's surface-driven expression, wherein the visual impact of the development—especially given its scale—is designed to supercede its spatial and programmatic depth. It is conceived and planned as a landmark-in-the-making to begin with.

In 2011, Bjarke Ingels Group revealed their designs for CopenHill in Copenhagen, also known as the Amager Bakke waste-to-energy plant, which repurposed its roof into a dynamic public space complete with a ski slope, hiking trails and a climbing wall. Finished in 2019, the project, especially owing to the media attention it got and the discourse it drew, ended up opening the room for discussions on the idea of "hedonistic sustainability", a concept coined and popularised by Bjarke Ingels himself, suggesting sustainable design solutions can enhance leisurely endeavours and the quality of life, rather than diminish or compromise it. By allowing visitors to engage with the waste-to-energy processes in action, the plant turns what is typically a hidden function of the building into an interactive part of the urban environment. In doing so, CopenHill sought to redefine a utilitarian infrastructure as a vibrant and sustainable civic space, blending ecological awareness with urban recreation.

In China, on the other hand, the growing shift towards indoor skiing and other similar 'simulative' facilities in the infamous “furnace” cities unfortunately comes at the cost of significant environmental strain. Typically requiring the maintenance of a consistent -6 degrees Celsius temperature year-round, operating an indoor ski slope involves using specialised cold storage systems and powerful cooling units that preserve snow and ice regardless of outdoor conditions and the levels of indoor activity. Furthermore, operating at nearly all times, these facilities consume vast amounts of energy to create artificial winter environments in regions lacking natural snowfall, even if the energy requirements may be offset through state-of-the-art principles of sustainable design, or the supply of energy itself may be supplemented by passive and renewable means. The Wuhan Ski Resort remains emblematic of this shift, offering engineered slopes, themed attractions and year-round programming within a subtropical context. As technology and capital grow to allow the proliferation of similar kinds of architecture all over the world, with entire contexts now capable of being fabricated, the idea of hedonism in sustainable pursuits, especially on an urban scale, remains one to reckon.

Name: Wuhan Ski Resort

Location: Wuhan, Hubei, China

Typology: Retail, sports

Client: Wuhan Urban Construction Group

Architect: CLOU Architects, Jan F. Clostermann

Design Team: Zhi Zhang, Sebastian Loaiza, Zihao Ding, Liang Hao, Yiqiao Zhao, Christopher Biggin, Principia Wardhani, Artur Nitribitt, Jing Shuang Zhao, Liu Liu, Yinuo Zhou, Yuan Yuan Sun, Haiwei Xie

Landscape Designer: WATERLILY DESIGN STUIDIO

Façade Engineer: China Construction Shen Zhen Decoration Co., LTD

Lighting Designer: Zhe Jiang Urban Construction Planning And Design Institute

Area: 178,000 sq.m.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 12, 2026

The New Government Quarter by Nordic Office of Architecture reimagines the site of the 2011 terror attacks as a porous civic district shaped by architecture, landscape and art.

by Bansari Paghdar Mar 11, 2026

Conceived by Pentaspace Design Studio, this cuboidal volume of exposed concrete and glass pegs movement as integral to the learning experience.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 07, 2026

Designed at the threshold of cultural preservation and rapid urban growth, the museum references geology, history and cosmology to create a global tourist destination in Medina.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 05, 2026

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Bruce Goff: Material Worlds moves beyond architecture to reveal the curiosity and cultural influences that shaped the American architect’s work.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Dhwani Shanghvi | Published on : Apr 16, 2025

What do you think?