Maze House in Ahmedabad bridges tradition and modernity in Indian architecture

by Pooja Suresh HollannavarNov 11, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Dec 03, 2024

Conservation work, particularly the conservation of built heritage is vital to a city’s identity: not only as a means to preserve traditional ways of building but also to preserve a tangible narrative of urban evolution. Heritage quarters and structures present material proof of the birth, reign and eventual death of rulers and kingdoms; the development of the city’s fabric: its accumulation of wealth and people, resources and cultures. By studying the structure and form of a city, as Aldo Rossi postulated in Architecture of the City (1966), we can learn about its history, evolution and relationship to society. The primary elements that make up the city, as he notes, are monuments and urban artefacts, defining the city’s character. For Rossi, urban development was affected by various factors, each dependent on the perception and underlying influence of these urban artefacts; some quarters accumulating collective memory and hence vital to the city’s perception.

Typically, architectural conservation champions heritage buildings, those that have been a part of dominant narratives of history, with the old quarters or areas around these places, either fixed up or left to degenerate. These spaces, while derelict, still hold the collective memories of the people who live there, providing contextual clues as to the city; ‘urban artefacts’ with their own form. These become especially vital in today’s age, adamant on rapid development and visible progress. While conservation efforts do their best to preserve parts of the city as authentic, this very idea of what authenticity is must be examined. The collective memory of a city presents a new way to think about and do conservation. An ongoing process of conservation then brings into conversation not only the fact that cities change, but the idea that this history of change is determined by what endures, or what we determine should remain.

Nani House, a late 20th century private residence, is currently being transformed into a locus for conversations about the ongoing maintenance of heritage structures from the era and redevelopment efforts in the locality and the city of Jammu overall. The brainchild of an architecture, design and research agency of Indian architects—blurck, the project combines participatory workshops along with design exhibitions, positioning the effort of architectural conservation and education around it as a collective practice. In this way, the design team hopes to “generate new values for an abandoned building amongst the people of the city”. The team uses the abandoned residential architecture as a platform to allow the local community to bring forth and actively discuss in conversation about the built environment. This, as they see, is essential; not only for better development but a more holistic built environment.

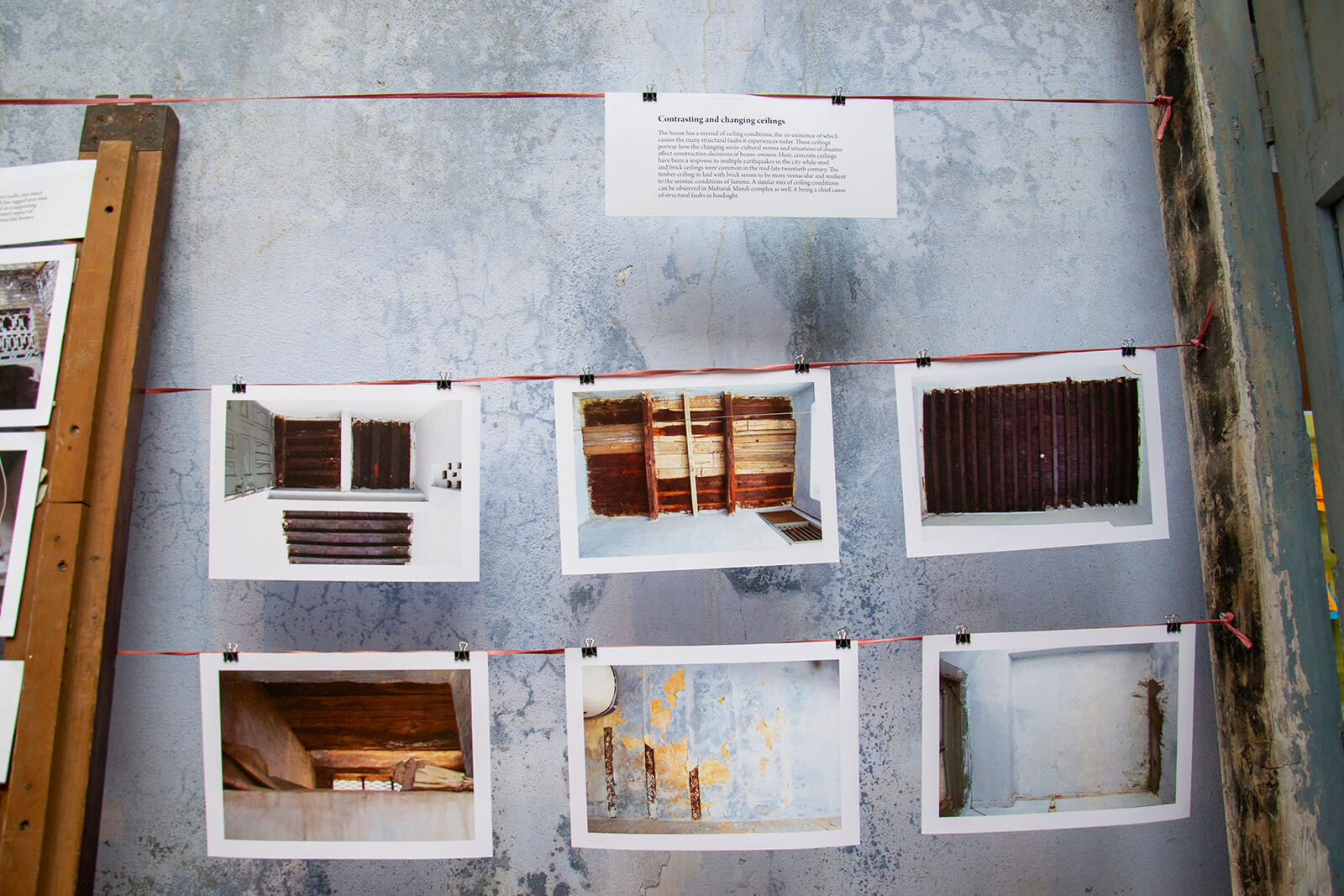

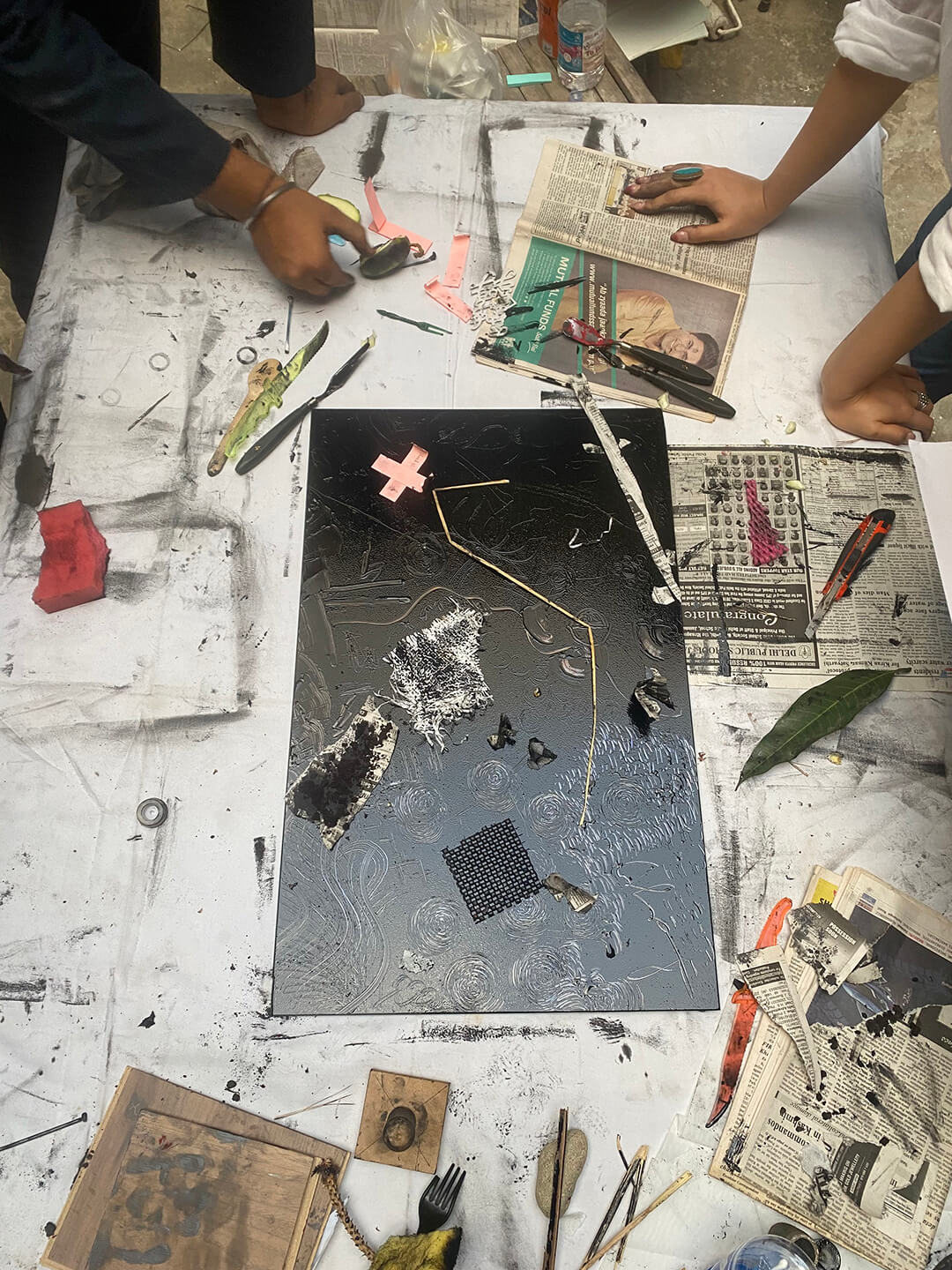

To date, the Indian architecture practice has put on a series of workshops and a documentary exhibition in the cultural space. The workshops, conducted in 2022, were centred on heritage walks exploring the surrounding areas of Link Road and Jain Bazaar, sketching trips for documentation and a printmaking workshop that utilised material from the house that forms the primary site of this project. The second participatory event within the public space was an exhibition which showcased works developed during a residential photogrammetry and documentation workshop, conducted in the summer of 2024. According to the team, these exercises allowed for a more intimate engagement with the building, bringing into conversation its many histories and lives. The second series of workshops and eventual exhibition, Ghar ki Baat, hoped to study the building rigorously, noting how the architecture had changed over time and how these changes were influenced by extraneous factors.

As the study revealed, the residential design over almost 100 years, had seen a horse stable converted into a dining space, the timber ceiling replaced with concrete (as a response to an earthquake) and lime plaster replaced with synthetic paint for the facade. The documentary photographs displayed in the exhibition space helped many visitors connect to the house’s built story, relating to the intimate spaces of the courtyard architecture; which over time has disappeared from buildings. Hence, it opened up a space for neighbourhood discussions on the needs of a house and a city; about vernacular design and the prominence of architecture in our lives. Through the exhibition of a regular residence in an affected area, the design team aimed to bring broader questions into discussion: “Once a building is built, it gets maintained within socio-ecological scenarios that might be unpredictable and are often neglected by designers. What does that mean for us as design professionals? How do we create methods of tuning in and listening? Is advocacy a hat that some of us must wear?”

The northernmost state in India, Jammu and Kashmir boasts rich natural landscapes as well as cultural heritage. The city of Jammu alone, known as the city of temples, features pilgrim routes, palaces, forts and streetscapes; developed from a storied past. The Bahu Fort and the River Tawi shape the identity of the city. While the state has for the better part been under occupation due to communal tensions, persistent efforts are being made by the city government towards the preservation of the city’s cultural identity. These efforts also fall in line with the current tourism policy of the state, which aims to make tourism a major engine of the area’s economic development. However, there is still criticism about how the Jammu Master Plan 2032 does not have a beneficial vision for developing heritage and tourism in the city.

Aiming to broaden conversations about the maintenance of heritage within the city, Bhavya Jain, one of the members of the studio notes in a conversation with STIR, “We imagine [Nani House] as a social space by slowly increasing its value. Through this process of slow conservation, we want to be able to talk about what's happening in the rest of the area in terms of water issues, earthquake issues and the like.” In their current work, the design team has uncovered the many ways in which the house has seen changes, a palimpsest of its users' needs. “We are trying to understand how the building was built and how it was rebuilt over time. When an earthquake occurred, someone changed a timber roof with a concrete roof; someone added a wall because there was an addition in the family etc,” Jain notes. “When we presented these findings to the community, it was around this narrative. In our research, we also figured out that the house had been designed by an architect. Then the question becomes, can you call it vernacular or not?” The tangibility of the building not only marks time but becomes a way to study how the area has evolved, not just for the team but the local people.

The project not only brings up questions about the development of the city and the eventual destruction of some of its older blocks, but it also brings to mind Rossi’s theories about the construction and evolution of cities; the marking of urban artefacts as measures of these factors. While in the documentation stage, the team has been able to bring out qualities and construction practices to educate local communities about the relevance of architecture and vernacular traditions, these discussions also act as active agents to bring up questions about government involvement in redevelopment. “I wouldn't say the government has largely neglected that area. But there are a lot of associations in the vicinity: like the jewellers' associations, textile sellers' associations and so on. It’s essentially mixed-use, with markets intermingled with the houses. Between the associations, the government and the smart city mission, some things do get left out,” Jain notes.

“There's no basic system of waste management, for instance. When we started looking at the project at a larger scale and not just at the house scale, this became one of our primary concerns.” As to the next steps, the team is currently working on proposals for the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), a heritage organisation based in India where the house would serve as a hub for professionals as well as the community to gather and engage with their context. The designers also hope to develop a plan of action with the J&K tourism department. Care and maintenance towards our buildings and fruitful discussions of these issues are still subjects of ongoing debate and are continuously refined by practitioners. Nani House presents a way to think not only about wider discussions of the built environment but how involving communities can lead to more care and more attention to these ideas as well.

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 16, 2025

For its sophomore year, the awards announced winners across 28 categories that forward a contextually and culturally diverse architectural ecosystem.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Dec 03, 2024

What do you think?