Compelling shows and practices from Asia that captured our imagination in 2024

by Manu SharmaDec 20, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Srishti OjhaPublished on : Aug 01, 2025

Jhaveri Contemporary’s latest exhibition, Roots of the Earth, is not the return to purity, tradition or homeland that the title implies. Instead, artists Prabhakar Kamble and Akshay Mahajan present reinterpretations of powerful symbols associated with religion, regionalism and the caste system in India, unpacking the oppression they enable. Collages in the form of sculpture and wall-sized tableaus employ far-ranging iconography—from tribal idols, Hindu temples, regional folk tales, to government surveys and the work of craftspeople whose vocation is defined by their caste—to depict the systems and conflicts that shape the lives of rural communities and inform interpretations of folk art and objects in contemporary art and culture. A multimedia artist and curator, an anti-caste approach informs Kamble’s artistic practice and activism. In this exhibition, he turns to his hometown, Kolhapur, highlighting the lived experience of local craftspeople and daily wage labourers. Mahajan’s practice draws from photography, where he uses the camera as a tool to explore the nuances of postcolonial reality. The works featured in this exhibition are inspired by his wife’s Assamese heritage and situated in the state’s Goalpara district. The resulting exhibition is a patchwork grounded in terracotta; it speaks of a country that lionises its folk traditions and artisanal goods while obscuring the lives and struggles of the people and communities behind it.

Kamble uses their identity as craft objects to question how religious and social elites appropriate and Sanskritise (alter to fit the grammar, aesthetic and values of dominant caste groups) art forms and trades practiced by lower-caste communities by religious and social elites.

Entering the gallery, one sees two long, maximalist sculptures suspended from the ceiling. Strips and balls of woven and synthetic fabric, brass bells, ropes of conch shells, meat hooks, ghungroos and nylon cords create a cacophony that conceals the simple, everyday terracotta pots stacked underneath. Some of these materials would seem familiar as cheap mass-market buys and others as handmade objects imbued with religious or cultural meaning. In Kamble’s sculptures, both categories of objects are mass-manufactured products that are almost unsettlingly squeaky-clean and new. The pots underneath, created in collaboration with Kolhapuri potters, are household items used for measuring. Here, they become a metaphor for the oppressive caste hierarchy and its measuring of human value, hidden by the pomp and circumstance of religion and culture.

The kinetic sculpture, Material Turn (2025), employs similar materials and aesthetics, affixed to a motorised arm resembling a sugarcane juice crank. Every five minutes, the sculpture turns with a noisy clanking reminiscent of cowbells ringing as they walk. It is a tribute to sugarcane farmers: among the first to be exploited as indentured labourers by imperialists and overrepresented in the rising statistics of farmer suicides as a result of predatory loans. The materials chosen emphasise the shadow of caste hierarchy—the ropes symbolising the bondage, labour and deaths of sugarcane farmers and meat hooks depicting the prejudice against lower-caste communities for their meat-based diet by orthodox upper-caste Hindus; the cowbells, meanwhile, stand out sonically and symbolically for their use as an instrument of humiliation and abuse in caste-based hate crimes.

These pots are also at the centre of Kamble’s Utarand series (2022-25). Kamble uses their identity as craft objects to question how religious and social elites appropriate and Sanskritise (alter to fit the grammar, aesthetic and values of dominant caste groups) art forms and trades practiced by lower-caste communities by religious and social elites. The first of the two sculptures in the series features an elephant in what Kamble terms a ‘bold indigo’, a colour referencing Dr B. R. Ambedkar and the anti-caste movement. The next, a white sculpture with a golden horse on top, recalls Hindu temples, which, although built by labourers and craftsmen from the Dalit community, often exclude their creators after they are opened and inaugurated. Kamble asks: When Indian craftsmanship is romanticised and venerated, is it the creators who benefit? During an exhibition walkthrough, Kamble said, “There is a difference between being anti-caste and annihilating caste. It’s the difference between calling someone a Dalit and an Ambedkarite. When you say Dalit, you ask if he can enter the temple; when you say Ambedkarite, you ask: why does he need to enter the temple.”

At the same walkthrough, Mahajan described the inspiration behind his series People of Clay (2017 - present) featured in this exhibition. He recalls hearing his now-wife humming and singing folk songs during quiet moments. When asked about them, she responded that they were like prayers, or “roadmaps for a people that have been disappeared from the map”. Thus began Mahajan’s exploration of Goalpara, an area of lower Assam bordering Bangladesh. He was fascinated by oral tradition and folk culture, but dismayed at its incomplete, colonial documentation. For Mahajan, the challenge was capturing the aliveness, spontaneity and polyphony of the culture and its stories without fixing and flattening them.

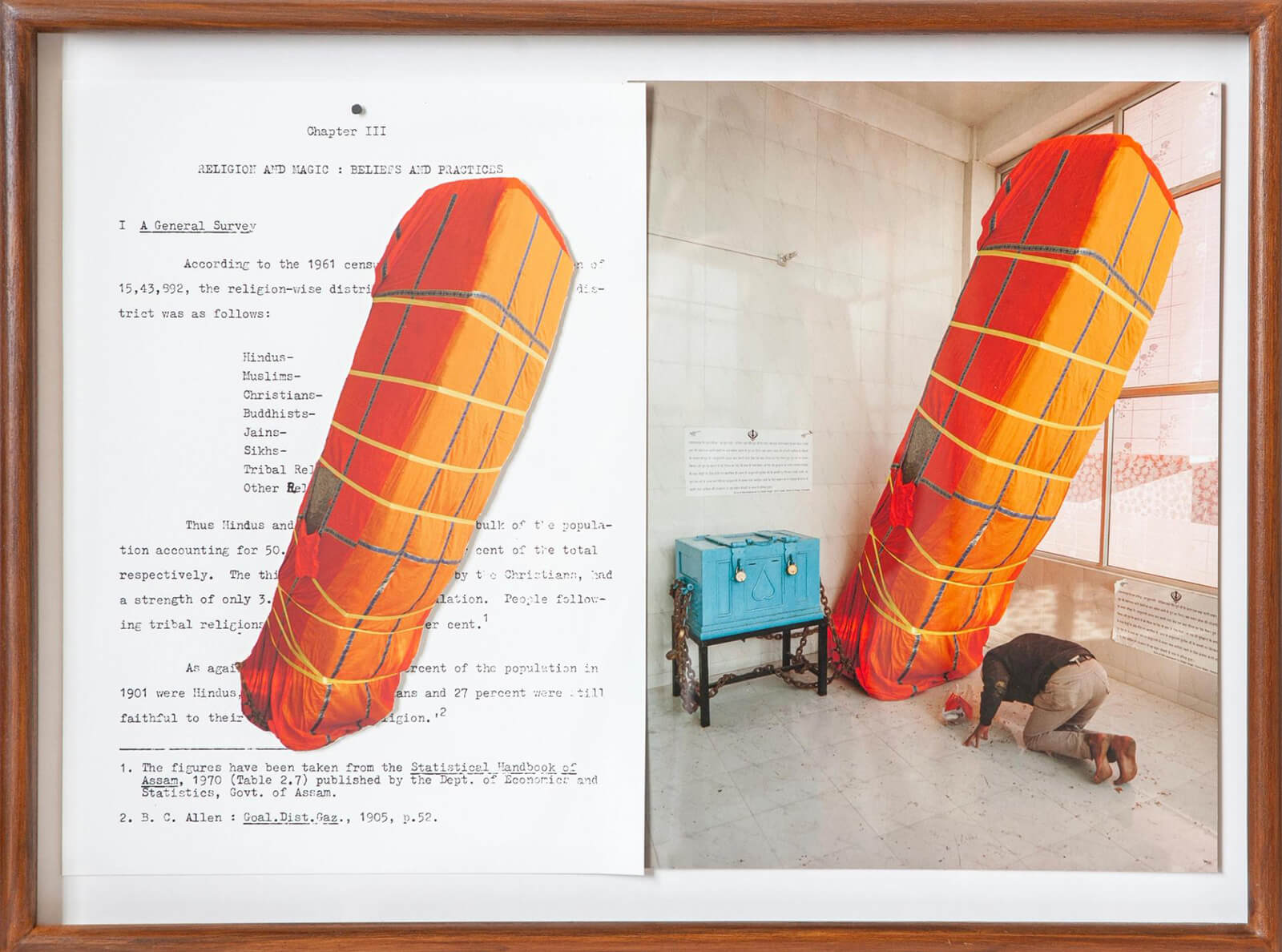

His photographic work, presented in fragments through collage, is an attempt to challenge and reimagine such forms of documentation. In People of Clay (The Stone and Magicians) (2025), for example, the image of a man bowing before a monolith references a story of magical intervention in a historic war the Assamese and Sikh people fought side by side. It is cut out of its cultural context and superimposed on a government survey of religious and magical beliefs, showing how living practices are flattened by recording, categorising and quantifying.

One of the central tableaus, People of Clay (Crows bring rain) (2025), shows layers of present-day and archival photographs of everyday life, village surroundings, food and art; fabric cutouts; poetry; pages from colonial anthropological texts describing Goalpara and its locals; and examples of traditional terracotta idols. The Hatima dolls, which are featured in the tableau in their sculptural form and as images, were created by women of the Asharikandi village from riverside clay, representing a generational tradition and spiritual connection with the clay that forms terracotta. Sholapith—masks and decorations made out of river reeds and leaves are included, illustrating the relationship between the artistic tradition of the local community and the land and ecosystem. Ethnographic texts intercede, writing under the image of a man, "Aboriginal. Now Hindoos.", revealing the colonial government’s obsession with tribal classification, a form of bureaucratic violence that continues to this day.

The theme of construction and reconstruction is a constant in Mahajan’s works, for example, in People of Clay (Daughter of Elephants) (2025), through his photographs of the construction of a new religious statue, Mahajan captures the moment mythology reaches and is realised in the material world through craft. He describes the ability to interrupt the documentary image and postcard representation of regions that collage offers by allowing one to deconstruct and reframe the image’s grammar.

Mahajan’s work explores folk psychogeography and asks what is erased, renamed or decontextualised in the process of moving from the oral to the written and from community to nation. He worked with local artists, theatre groups and nomadic bards for many works in the series, such as People of Clay (Blind Bard) (2025) and People of Clay (Behula and Lakhamindra) (2025). The latter occupies an interesting position between staged and naturalist photography as an image the photographer captured after stumbling upon a local filmmaker who was making a movie about the epic love story of Behula and Lakhindar, a significant part of Assamese culture.

Despite representing different regions in the subcontinent, both artists are invested in how regional or marginal communities are represented in mainstream Indian art, history and culture, and what is lost on the journey there. Kamble's and Mahajan’s work urges viewers to move beyond romanticising handicraft and folk art, by drawing our attention to the political and material circumstances of the regions and communities they emerge from.

‘Roots of the Earth’ will be on view at Jhaveri Contemporary from July 10 - August 16, 2025.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Srishti Ojha | Published on : Aug 01, 2025

What do you think?