Dela Anyah discusses value, waste and sustainability with ‘Beyond Rubber’

by Kwame AidooJan 13, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Kwame AidooPublished on : Jan 28, 2025

The exhibition Ghana 1957: Art After Independence, curated by Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh, Elizabeth Asafo-Adjei and Ashley Miller at the National Museum of Ghana, Accra (September 21, 2024 - March 29, 2025) is on the one hand crucial and on the other, overdue.

The show opens space to celebrate Ghanaian modernist art and explore connections between pioneering artists, collectives and institutions while collaborating with the general public to unearth missing links. One personality worth remembering is Ghana’s first and probably only official “state artist” Kofi Antubam (1922-1964). The title was bestowed on him by Dr Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of the newly independent country, on account of Antubam’s creative skills and knowledge in cultural history that captured the spirit of the post-colonial Ghanaian identity. The objects he made could have easily been treated as artefacts of colonised cultures a century prior to his existence.

Besides naturalist woodwork techniques involving arduous craftsmanship and elaborate details, Antubam shrewdly introduced Adinkra symbols (ancient philosophical concepts of the Akan group) in his works, as seen in State Chair and footstool (1956). Made with white wood (sɛsɛ), gold leaf and paint; the furniture was used in Ghana’s parliament house for decades and is coded with the following Adinkra: Mmusuyidee (meaning bad luck remover) on the seat, arms, footstool and prominently on the backrest encircled by Adinkrahene (meaning authority). Dwennimmen, which stands for humility and strength, is carved on both legs. The artist’s poignant documentation takes into consideration the architectural frameworks and familiar vernacular objects that surround his characters, like in the oil painting How Much? (before 1954), where he illustrates women trading food.

Other works consider leadership during the postcolonial beginnings, like the colour photo Portrait of first Prime Minister of Ghana (around 1960) made by an anonymous photographer. The work shows Nkrumah adorned in kente cloth with a gold watch on his left wrist. Mounted with an orange background with a coat of arms sticker and framed with wood, the image communicates the charisma of the leader who spearheaded the consciously modern Ghanaian identity.

The coat of arms appears in other guises in the show. The symbol can be seen sculpted into a commemorative stool (called Asεsεgua by the Akan). It was made by carvers based in Nankese, Ghana’s Eastern Region. Nii Amon Kotei (1915-2011) was the designer of the symbol which was launched two days prior to Ghana’s independence. In Kotei’s acrylic painting Census (1959), a traditional head flanked by two stool kinsmen, bearing traditional umbrellas, is focused on oversized bead-like objects and cowries, a signifier of wealth. Kotei’s oil on board work Mother and Child (1971) conveys the intimate nourishing moment of motherhood, with a golden background making the symbolic encounter more conspicuous.

Out of two works on display by Ernest V. Asihene (1915-2001), the more abstract one, Peep into the Future (1963), made with watercolour and gouache on paper, begins like a tapering tunnel that leads to a mystical silhouette. More mysticism is featured in The Pot of Beans (1949), another masterpiece by Asihene which is a page from the Kwaku Ananse (fictional Akan character) folklore about greed and its associated ignominy. The same year the artist made this painting, the Coussey Committee was established, after the 1948 Accra riots, to draft a constitution towards Ghana’s self-rule. The riots were caused after British police superintendent Colin Imray shot and killed three local unarmed ex-Second World War servicemen.

Aside from folklore, proverbs are also rich allegorical forms from ancient days that artists from the modernist circles borrowed to fuse their works with tradition. Obi Nkyerɛ Kɔmfoba Kosua di (1973) by R. T. Ackam means ‘one cannot teach a traditional spiritualist’s child how to eat an egg’. Here, the egg which is used in customary spiritual affairs, is used in the proverbial title and the painting seeks to draw on an ironical conundrum. Philip Morland Amonoo (1922-2011), like Ackam, used oil on masonite as the medium while articulating traditional reverence and customary recognition with his work entitled Naming of a Child. The Guitar Band by J. D. Okae (1916-1988) exudes the warm ambience of palm wine highlife music of the pre-independence era. While Atta Kwami channels a geometrically warped presence in Farmer (1976), J. C. Okyere (1912-1983) uses Arbor Vitae (1956) to lucidly render women growing branches of palm from their scalps while rooted in otherworldly verdure.

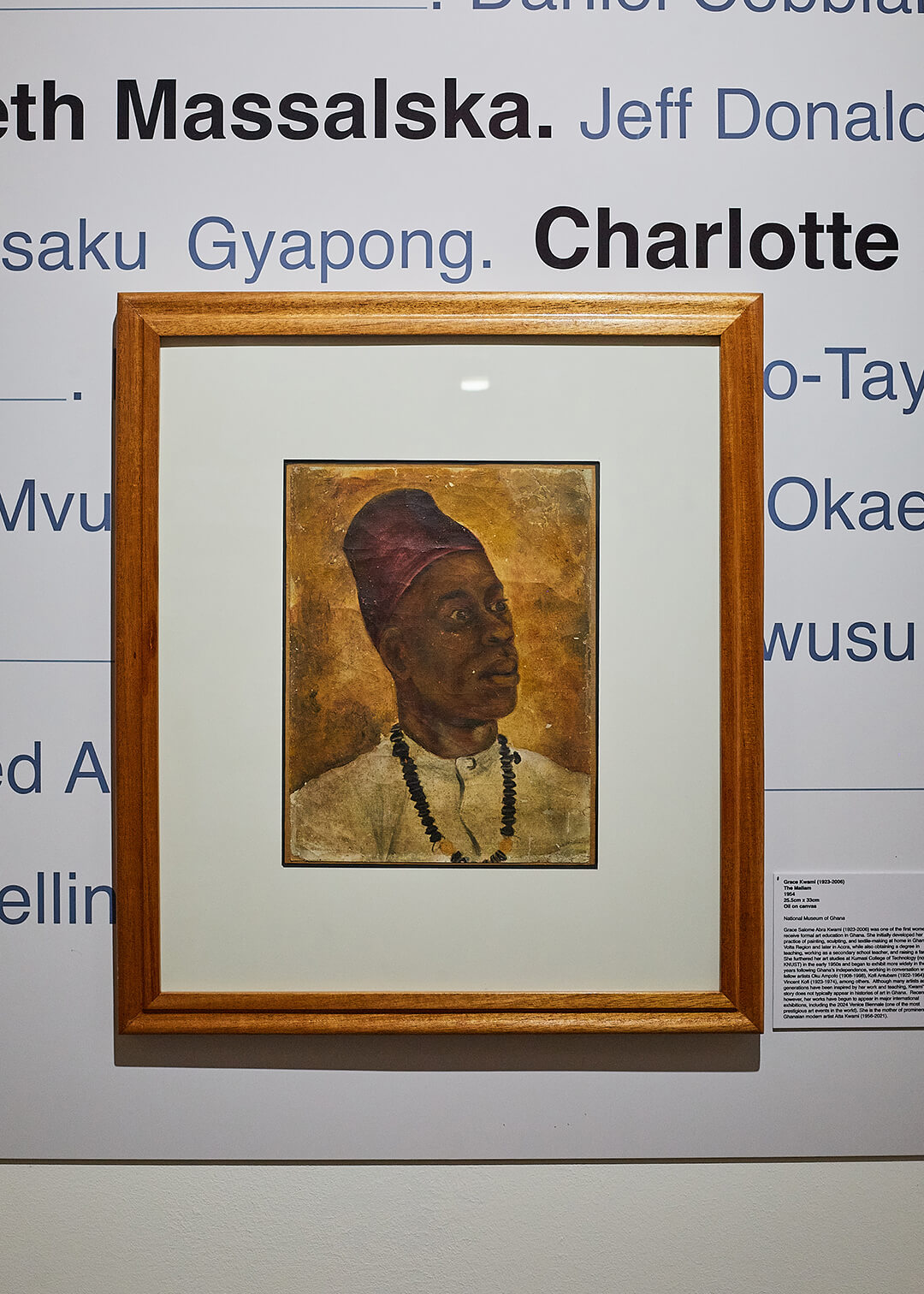

As we unearth the histories of the modernist era, this exhibition takes on the imperative task of acknowledging some of the women who did their part to make the movements possible. Grace Salome Abra Kwami (1923-2006), mother of the late abstractionist Atta Kwami, was among the first Ghanaian women to receive a formal art education in Ghana, later going on to teach. Her oil on canvas portrait The Mallam (1954), exposes the meticulous flexibility in her figurative style, while seemingly paying homage to a community head. Her art appeared in exhibitions after Ghana’s independence, in dialogue with decorated artists like Oku Ampofo, Kofi Antubam and Vincent Kofi – most recently, it was shown at the 2024 Venice Biennale.

Felicia Abban (née Ansah, 1936-2024) is one of the few photographers who rubbed shoulders with the camera-bearing men of her time; with her freelance position at the Guinea Press Limited – a publishing house connected to Nkrumah. In the mid-1950s, she opened the Mrs. Felicia Abban’s Day and Night Quality Art Studio in Jamestown, Accra, not far from J.K. Bruce Vanderpuije’s Deo Gratias and James Barnor’s Ever Young Studio. In her photograph, Untitled studio portrait of a woman (around 1960s-70s), she uses a vintage silver print to channel authenticity, audacity and radicality in the feminine spirit of her time, augmented by the tilt of the model’s head, eccentric eyewear and the slight parting of her lips.

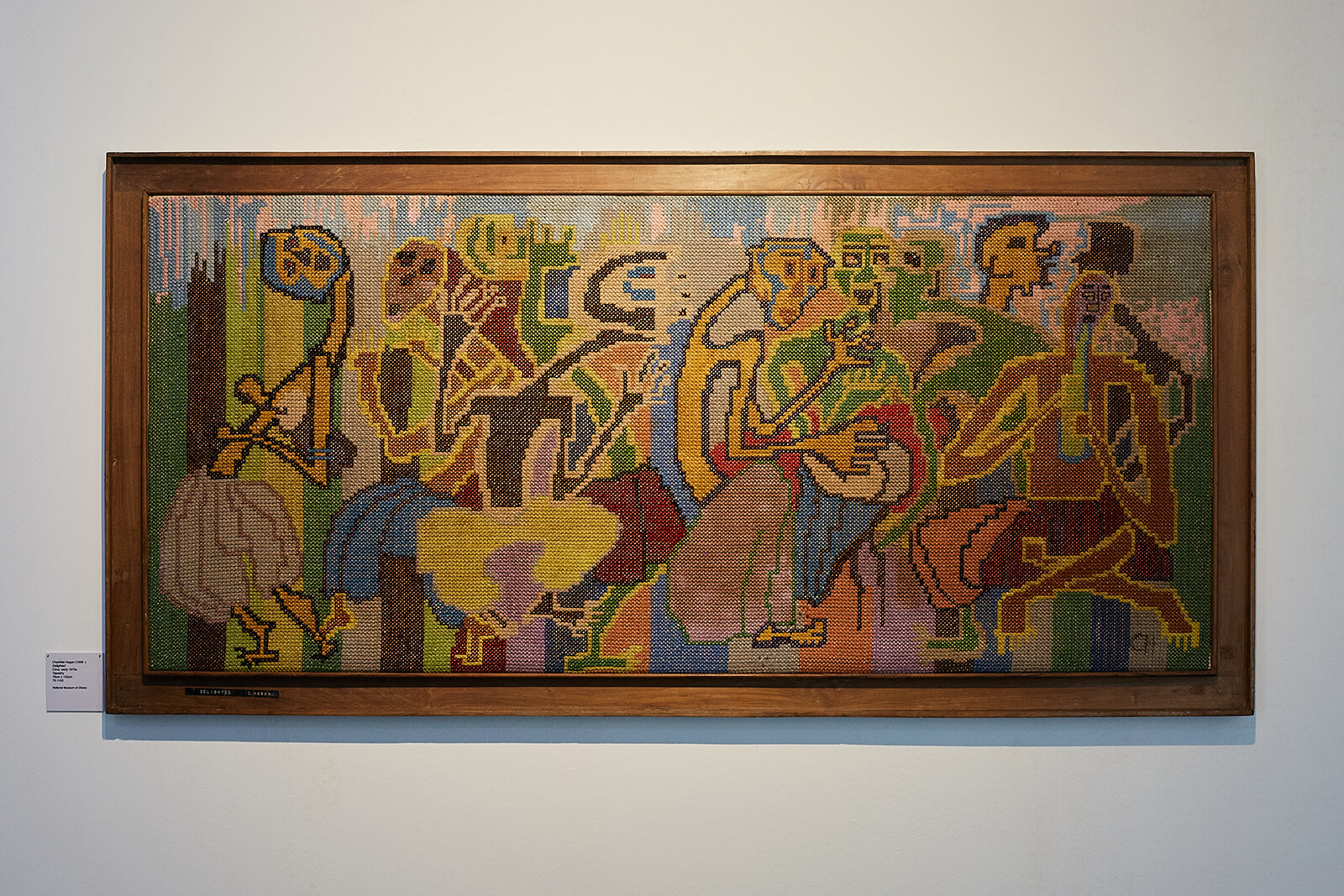

Colourful column patterns reminiscent of Northern Ghana weaving styles form the background of Delighted (around the 1970s). A framed tapestry work by Charlotte Hagan, its panoramic layering with thread-work creates a frenetic world of partially discernable figures playing instruments and dancing.

In addition to Kwami, Hagan and Abban, the works of other independence era women artists are slated for an upcoming 2027 exhibition which the curators believe will be a more monumental exploration of Ghanaian Modernism. On the other hand, one may ask, what about the women who did not go through institutions or collaborate with the men who had their careers acknowledged? Why is it that historically, rural Ghanaian craftswomen have not been documented as compared to the fine art elites? Maybe the more we question the sidelining and silencing, the better our chances of yielding brighter days.

In line with shedding light, it is worthy to note that three vast exhibitions organised by blaxTARLINES from 2015 to 2017, were initial hints towards bridging the gaps in the narrative. The projects were Cornfields in Accra (2015), The Gown Must Go to Town (2016) and Orderly Disorderly (2017). The intergenerational capacity of these shows allowed the general public to experience the contemporary while simultaneously appreciating some historical contributions due to the holistic and informed curatorial ethos. It is befitting then that blaxTARLINES KUMASI is, in collaboration with the National Museum of Ghana, the University of Michigan and other institutions organising this next colossal show in 2027 when Ghana will turn 70.

‘Ghana 1957: Art After Independence’ is on view at the National Museum of Ghana, Accra, until March 29, 2025.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Kwame Aidoo | Published on : Jan 28, 2025

What do you think?