A London exhibition reflects on shared South Asian histories and splintered maps

by Samta NadeemJun 19, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Manu SharmaPublished on : Dec 23, 2024

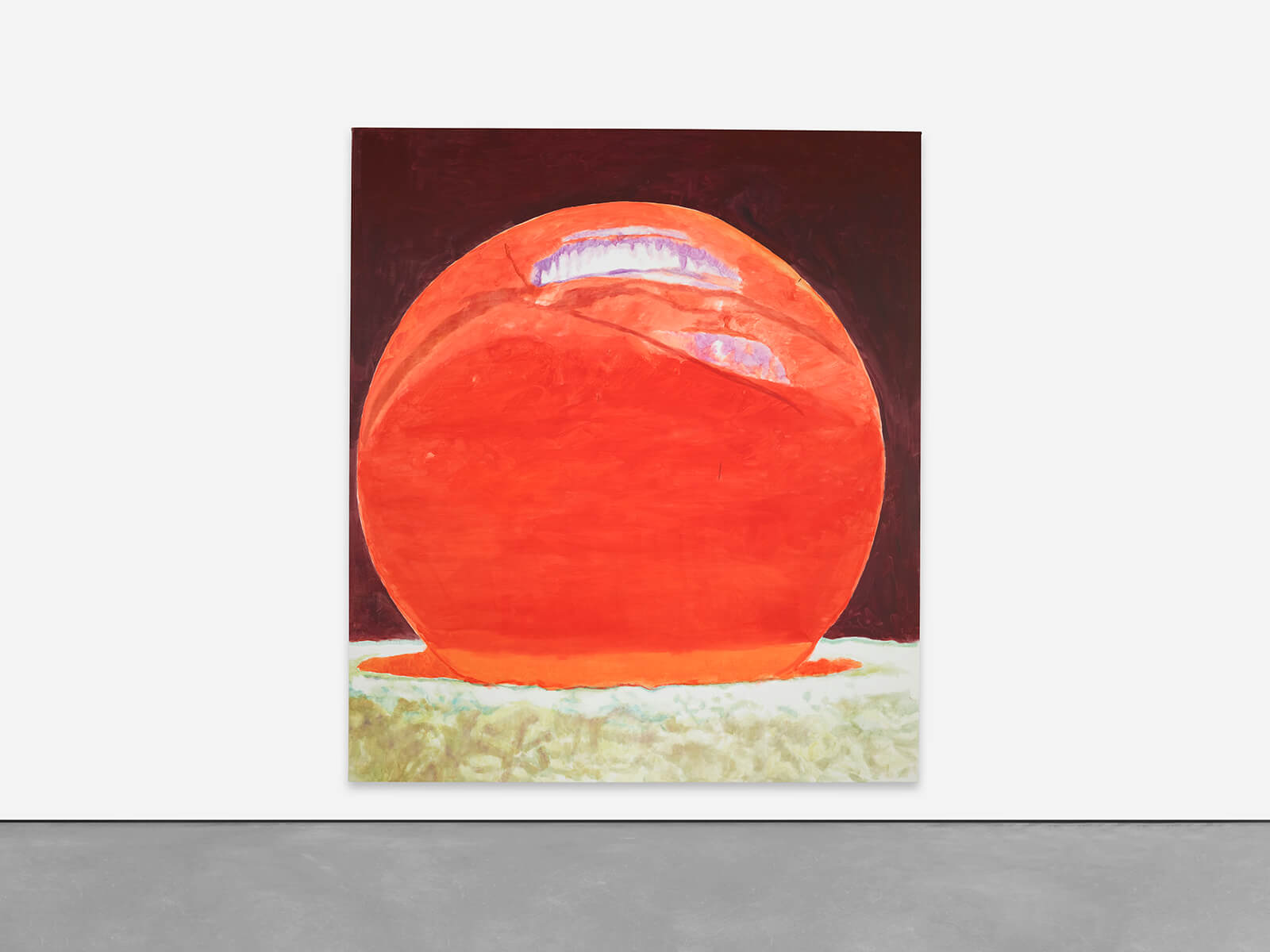

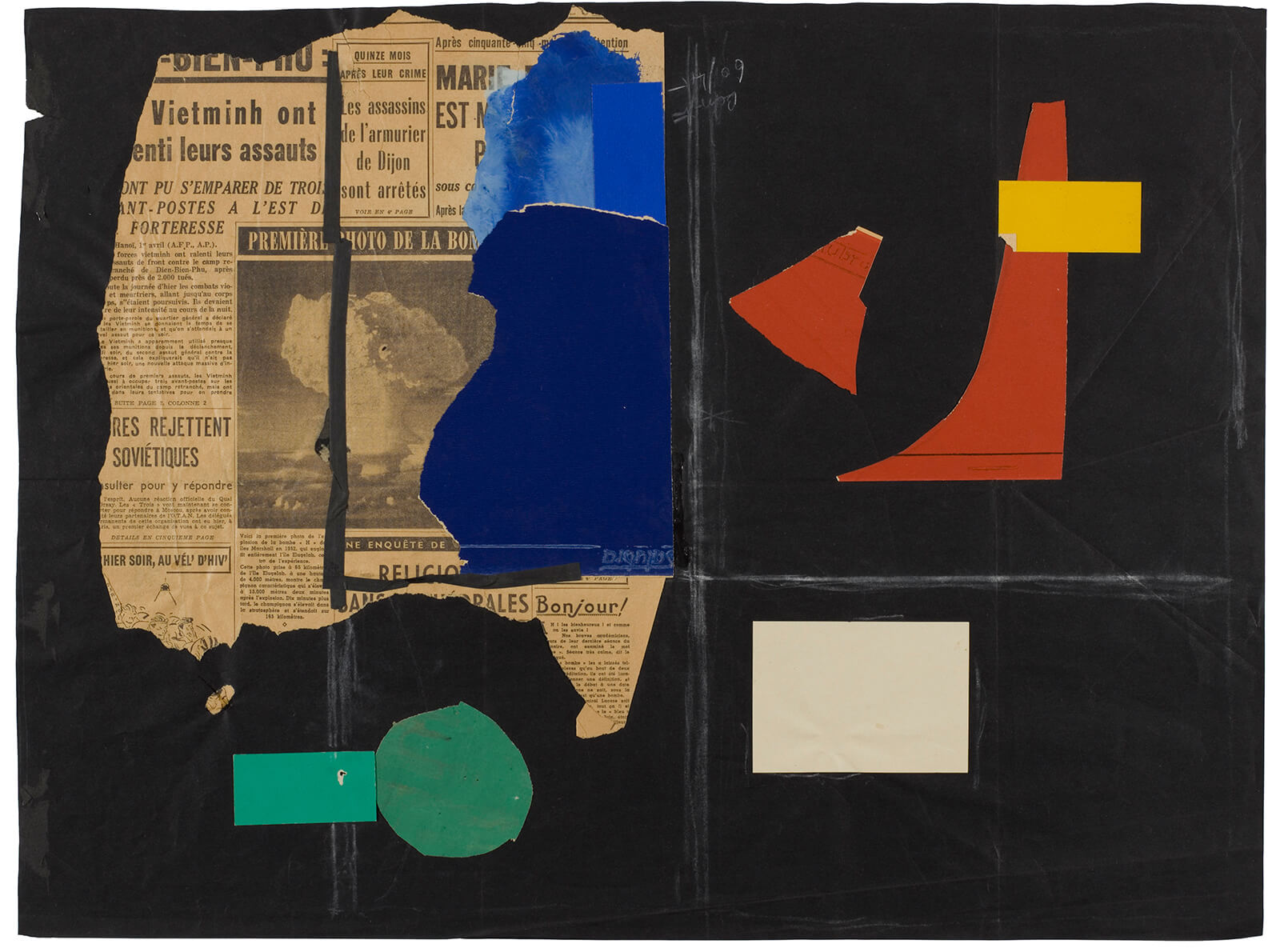

The Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris (MAM Paris) is currently presenting The Atomic Age, a group exhibition bringing together the works of several 20th-century artists who were inspired by atomic research and discoveries. The show is on from October 11, 2024 – February 9, 2025, and presents over 250 works of art across painting, photography, video art, installation art and more, highlighting varying stances in relation to the promises and perils of the atom. The show is curated by Julia Garimorth, head curator, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, and Maria Stavrinaki, professor of the history of contemporary art, University of Lausanne. Stavrinaki joins STIR for an interview that explores the exhibition in greater depth.

The drawings of hibakusha cannot be treated on the same level as other artistic practices. They are visual testimonies, elaborated by longue durée (long durational) memory. – Maria Stavrinaki, professor of the history of contemporary art, University of Lausanne

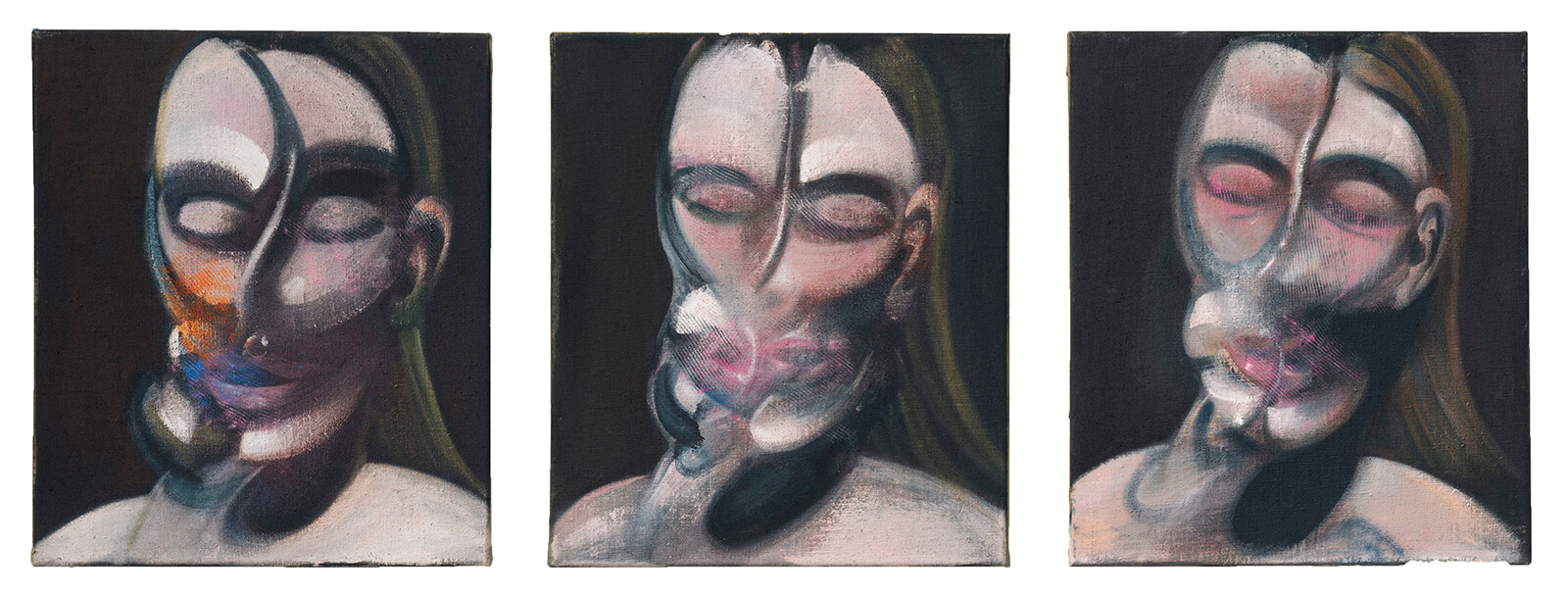

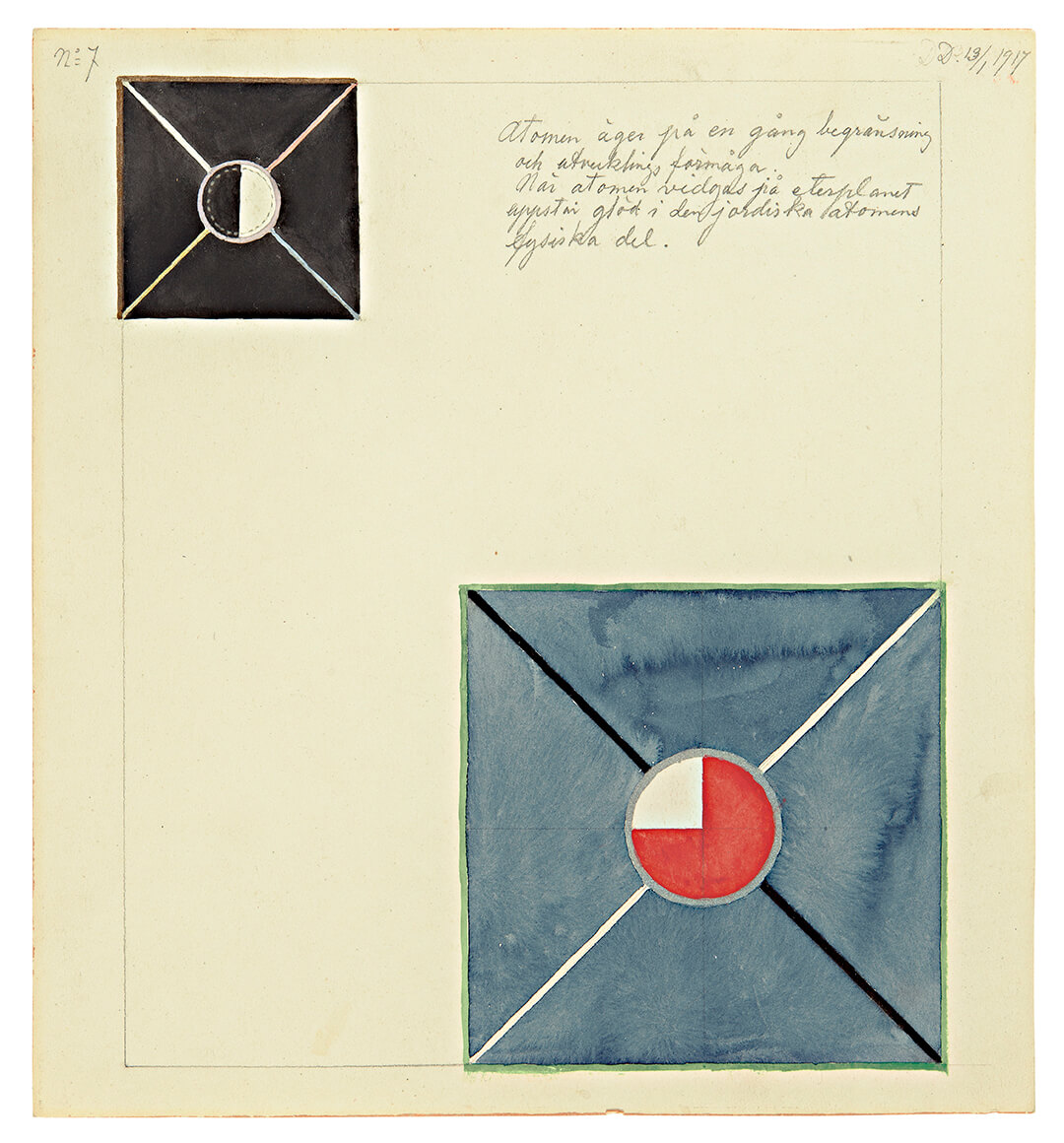

Hilma af Klint (1862 – 1944), Wassily Kandinsky (1866 – 1944), Salvador Dalí (1904 – 1989), Francis Bacon (1909 – 1992) and Barbara Kruger (b.1945) are some of the prominent names in The Atomic Age’s massive roster of artists. The first section of the exhibition focuses on practices including af Klint and Kandinsky, who were inspired by the work of atomic physicists and formed their perspectives on the atom before the world bore witness to its capacity for destruction (both artists—coincidentally—passed away a year prior to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki). As Stavrinaki tells us, “This section is about the imaginary uses of the atom, since the discovery that it's divisible and that it can radiate an unknown energy (radioactivity).”

In Kandinsky’s autobiography Rückblicke / Retrospect (1913), the artist writes, "A scientific event removed one of the most important obstacles from my path. This was the further collapse of the atom." New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford had theorised two years prior to the autobiography’s completion that he could split the nucleus of a nitrogen atom by bombarding it with alpha particles. Eventually, in 1932, English and Irish physicists John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton would successfully split a lithium atom’s nucleus into two helium nuclei. Atomic research was an area of great interest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and one that Kandinsky remained keenly fascinated with.

Theories and research surrounding atomic fission (atom splitting) forced the German artist to rethink his perception of the world around him. He began to perceive a hidden world beneath our own that came together to prop up the reality we interact with. In response, he began to subvert representation within his paintings from the early 1910s onwards, and by 1919 – 1920, he was creating the abstract art he is widely known for. Meanwhile, af Klint concerned herself with developing a visual language that would enable her to explore reality beyond our perception, such as the interactions between atoms. Stavrinaki comments on the significance of these practices, considering them critical in “the fight of artists against the flat appearances of nature”.

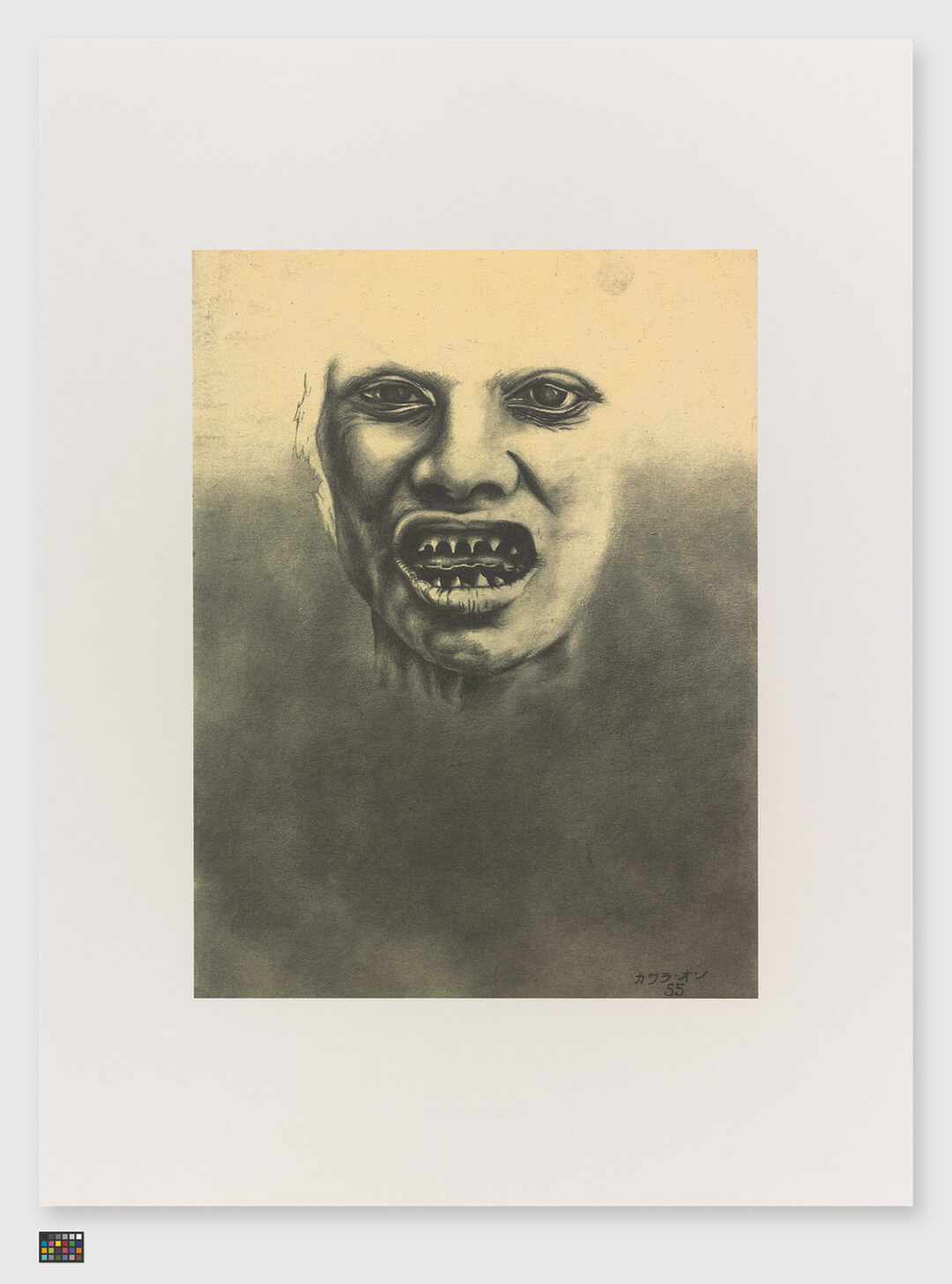

Other sections of the exhibition collect works created after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. The first among these is dedicated to Japanese practices, where the show also presents illustrations by 'hibakusha', the survivors of those bombings. The works created by these victims of war contrast jarringly with the romanticism of Kandinsky and af Klint. One particularly haunting piece is an illustration made with black ink of a child lying on its back with its arms and legs in a position of supplication. This bending of the muscles is indicative of a death that has occurred due to extreme heat. The significance of the black ink, then, is to tell us that the child is charred beyond recognition.

Stavrinaki places a justifiable emphasis on the drawings of hibakusha. The curator tells STIR, “After the bomb, artists and society at large did not react in the same way. There have been neutral, aestheticist reactions to the Bomb, artistic practices embedded within governmental politics and artists very critical of nuclear militarist politics. But beyond all that, the drawings of hibakusha cannot be treated on the same level as other artistic practices. They are visual testimonies, elaborated by longue durée (long durational) memory.”

The Atomic Age brings together an expansive and compelling body of works that raises some difficult questions. While nuclear physicists in the early 20th century became increasingly leery of atomic fission—a fear that Einstein would solidify in 1939 through a letter to United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt—many of the practices exhibited at the show could not anticipate the true extent of its destructive potential. We must then ask ourselves what such artists would have thought had they lived to see the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Similarly, we are pushed to consider how hibakusha would respond to these early, atom-inspired works by the likes of Kandinsky and af Klint. Perhaps most pressingly, the exhibition transcends its area of focus and prompts us to reconsider the promises of contemporary discoveries.

‘The Atomic Age’ is on view from October 11, 2024 – February 9, 2025, at The Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Manu Sharma | Published on : Dec 23, 2024

What do you think?