Atelier Sizhou's sports bridge in Chengdu evinces the tail of a Chinese dragon

by Simran GandhiSep 03, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Aug 24, 2024

Reportage from 2017 onwards already declares the 'legacy' of the Rio Olympics—or the intended afterlives of the public infrastructure, stadiums and other facilities such as housing built specifically for the event—mostly a series of "unkept promises". Owing to several factors, from the financial crisis in Brazil to the sites being built on land that was either reclaimed from local communities or otherwise inaccessible to them, these spaces lie in various degrees of disrepair. The abandoned sites present a peculiar conundrum, what happens to public infrastructure projected as being for the greater good, when the torch has been passed on?

It is fairly common for large sporting events such as the Olympics to leave behind unneeded facilities. A case in point to the contrary might be the recently concluded Paris 2024 Games, where the decision was made to reuse 95 per cent of existing sporting sites. However, it could be argued that bids for events that display national progress are made specifically banking on the construction of 'state-of-the-art' infrastructure. The question then becomes, is there a way to ensure these facilities are used by communities after the event? What factors play into either using or rejecting facilities? Who is responsible for the upkeep of such infrastructure, local or national bodies? The solutions proposed that work reveal a fine balancing act between public good and the desires of private development markets.

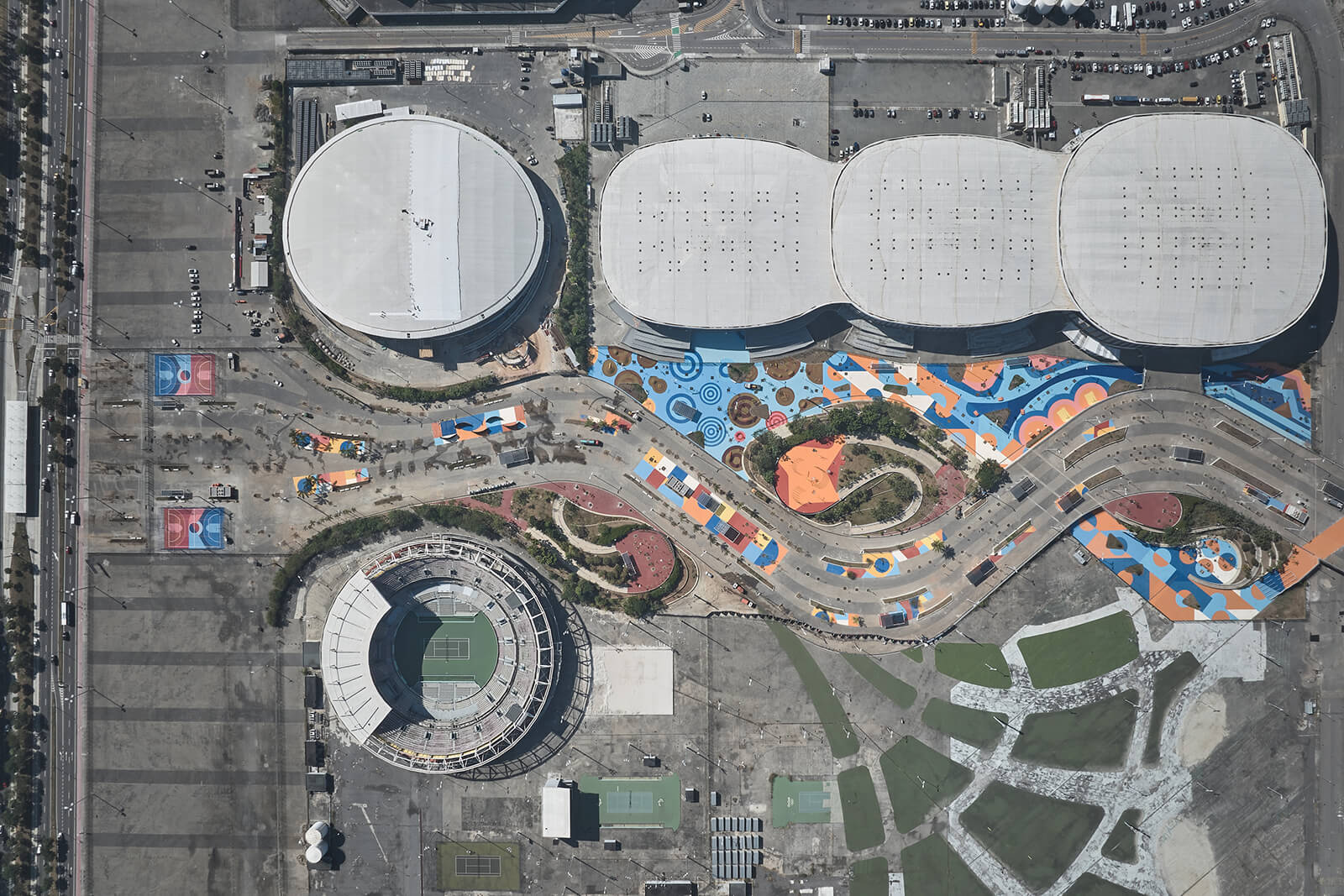

Recently, the Olympic Way, a pedestrian thoroughfare which connected the major venues of the 2016 Summer Olympics—as part of Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca, Rio—including the Tennis Center, the Cariocas Arenas and the Live Site, was transformed as part of the Rio Games’ Legacy plan. The Park, initially designed to accommodate large crowds and meet the high demand for public attendance, was anticipated to be adapted for new uses after the end of the Olympics. The initial project included a plan to build four schools on the site of the Arena of the Future, which has not been realised yet. However, in 2022 a proposal for the refurbishment of the thoroughfare was tendered by Rio de Janeiro City Hall. It called for the redevelopment of the Via Olímpica, Live Site and Garden Terraces into a public park, to increase vegetation on the site and create active public spaces.

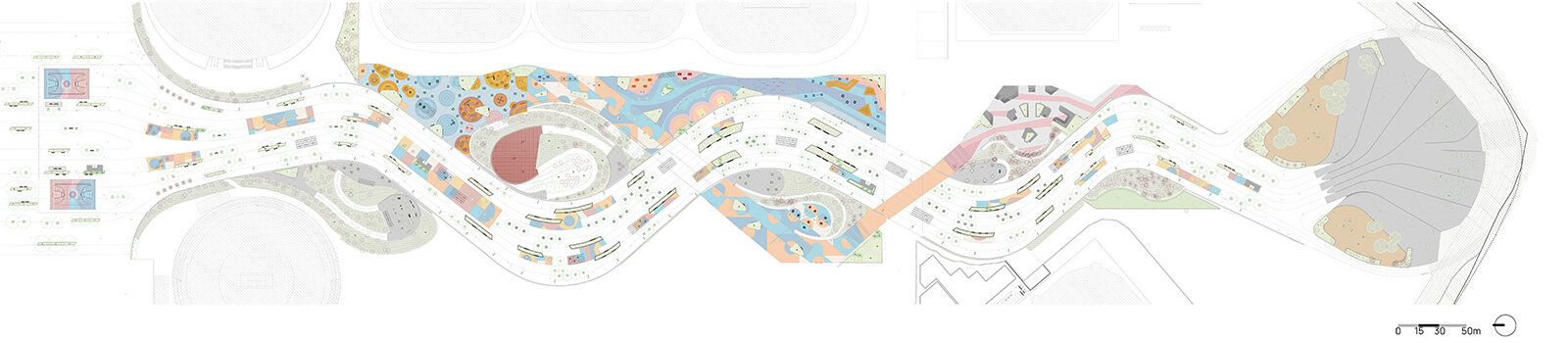

Renamed Parque Rita Lee in honour of the late Brazilian singer, the redevelopment of the Olympic Way and its immediate surroundings, an area totalling around 140,000 sqm into a space for public engagement was tendered to Ecomimesis, a Rio-based architecture firm. The driving principle for the project was to turn the defunct facility into “a landmark leisure destination for the city” that celebrated the vibrant culture of Rio, states an official statement by the architects. Aimed to enhance the facilities provided to the local community, the design team proposed diversifying the park’s functions by interspersing spaces of rest, landscaped terraces and play area along the pedestrian stretch.

Speaking about their proposal for the revitalisation of the once lively site, the Brazilian architects tell STIR, “During the development of the basic and executive projects, the original vision was preserved, with the addition of new green areas, increased recreational spaces and seating arrangements. However, minor adjustments were necessary to accommodate the park's role as a venue for major events, requiring consideration of the substantial foot traffic expected during such occasions. The vegetation beds along the road were strategically designed to guide pedestrian flows and facilitate large crowds, with areas most likely to attract high attendance positioned alongside the roadway." As to the park’s role as a venue for major events, the former Olympic site has hosted some sports events, and even Rock in Rio since 2017.

While Olympic officials and local organisers often paint infrastructure and sports architecture built for such an event as posing residual benefits for the host city and country, it’s worth questioning who truly benefits from these facilities, taking Rio as a case in point. The part landscape architecture, part urban intervention project by Ecomimesis addresses some of the drawbacks of the Olympic site post-2016 with carefully planned amenities and services. Divided into two park typologies—the Linear Park and Urban Park—to include two distinct and complementary uses and occupations of the space, the architects note, “The concepts of accessible, democratic, dynamic and interconnected spaces were fundamental to the Park.” The core philosophy for the project was to mitigate the perception of large empty spaces within the site, with a particular focus on the integration of nature into the territory.

While the Linear Park acts as a promenade focused on leisure, the Urban Park is a dynamic space for sports activities. Interventions for the linear park—a large avenue 60 meters wide and 1.2 kilometres long—include shaded areas and pavilions for rest and public restrooms. New landscaped spaces planted with native Atlantic Forest trees add to the liveliness and greenery of the site. Meanwhile, the Urban Park, which is essentially pockets of activity tied together by the main promenade includes recreation and leisure areas, play areas, sports courts and a distinctly colourful identity meant to attract visitors to the site. Some of the facilities planned for the Urban Park include a skate park, two multi-sport courts, two 3x3 basketball courts, an event area, a children's playground, a children's aquatic area, a game area (table tennis and futmesa), a picnic area, a senior fitness area, a climbing wall and public restrooms.

As the architects note, the urban planning interventions within the Urban Park were conceived with the notion that the park be accessible to all individuals and the amenities provided meet the needs of the local community. Based on ecological principles, the plan also accounts for the creation of more than 800 square meters of Atlantic Forest grove, tree planting with 1,100 new native tree seedlings and the addition of more than 8,000 square meters of permeable green area throughout the park. Hence, it is the hope that not only will the functional programme and colourful design of the site bring it alive, but the vegetation will too.

The execution of a project of this scale not only required intensive research, but from what the firm relays to STIR, involved studying the demographics of the region to understand who will use the park; thorough traffic and accessibility Studies; an analysis of the existing park and subsequent zoning for the redesign and a meticulous Environmental Analysis given that the project is part of a municipal network of green and blue spaces. As the architects emphasise in their official statement, the park is planned as part of a larger network of landscaped spaces within the city, aimed at rectifying the ecological damage caused by extensive urbanisation since 1969. The goal for these blue-green infrastructural spaces is to reconnect and re-establish meaningful ecosystem interactions between local fauna and flora and the built environment. Hence, as the architects reiterate, the project aims to “reconnect residents with nature, encouraging awareness of the nature-biodiversity-society relationship, particularly regarding ecosystem goods and services.” The tying of Via Olímpica’s redevelopment to the existing programme of blue-green infrastructure in Brazil further points to a reconception of how legacy plans might tie into sustainable design endeavours and ongoing urban strategies for renewal.

With a focus on the planting scheme and the attempt to tie the natural with the built context in the project, the architects mention that they faced significant challenges, given that they were working on a brownfield site, the former Olympic Park masterplan by AECOM. As they go on to tell STIR, “One challenge encountered during the process was the planting along the Via Olímpica. During the construction of the Olympic Park for the 2016 Games, this area underwent significant modification and was filled in to create the 60-meter-wide elevated route known as the Via Olímpica. As a result, the soil was highly compacted, presenting difficulties for the planted species in developing root systems.”

They further mention strategies they implemented to counter this hurdle, including employing raised beds at the highest points of the route which utilised suitable nutrient-rich soil. Trees planted along the promenade were planted in large cradles that were excavated and filled with appropriate soil. They go on to note, “The slope along the road further constrained the proposal of activities such as courts and playgrounds, which were limited to the flatter areas of the park: the urban park, characterised by vibrant colours, the Live Site and the Terraces. The linear park, designated as the Via Olímpica, was reimagined as a space for connectivity and passage between the raised beds, incorporating strategically placed seating and shading elements along its route.”

While the Brazilian architects hope to engender a sense of public engagement through their design, one may ask how effective this intervention will be. Another question that springs to mind is whether intervening in open spaces such as the Olympic Way proves more convenient, and cheaper even, while the structures of the Park stand as “white elephants”? How will the communities around these sites be affected by the inevitable price rise in the area? These questions, while they seem disparate are intrinsically linked, and the role architecture and design play in questions of development and real estate, of how planning can disenfranchise certain communities cannot be overstated. To the first few questions, the landscape design project for the park seems to present a solution that not only takes into account public needs but looks to integrate what was originally a fallow site with nature.

Noting the importance of introducing nature to such a site, the firm tells STIR, “It is of utmost importance to our firm to reconnect public park users with the local nature. [Our] efforts aim to restore the presence of nature in such an urbanised area. We believe that the park effectively balances its urban aspects with its role as a landscape connector, situated in a characteristic area of Rio that links a lagoon to a highly urbanised zone.” On a hopeful note, they conclude by saying, “Considering the natural growth cycle, we believe that within 10 years, with the growth of more than 1,100 trees planted and over 8,000 square meters of permeable area with shrub vegetation, the park will play a more significant role in reducing the heat island effect in the region." The architects not only redefine the nature of intervention within such sites but through the design present a model for redefining urban spaces for greater integration with nature. While the arenas sit vacant, maybe in 10 years, there is hope that the promises might still be fulfilled.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 12, 2026

The New Government Quarter by Nordic Office of Architecture reimagines the site of the 2011 terror attacks as a porous civic district shaped by architecture, landscape and art.

by Bansari Paghdar Mar 11, 2026

Conceived by Pentaspace Design Studio, this cuboidal volume of exposed concrete and glass pegs movement as integral to the learning experience.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 07, 2026

Designed at the threshold of cultural preservation and rapid urban growth, the museum references geology, history and cosmology to create a global tourist destination in Medina.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 05, 2026

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Bruce Goff: Material Worlds moves beyond architecture to reveal the curiosity and cultural influences that shaped the American architect’s work.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Aug 24, 2024

What do you think?