The home and the world: Rashid Johnson’s multivalent Black selfhood

by Avani Tandon VieiraJun 24, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Marcus CivinPublished on : Apr 14, 2024

In the upstairs gallery at New York’s Magenta Plains, Stan VanDerBeek’s roughly five-minute film Skullduggery (1960) refers to some of the major political events of his lifetime up to that point. It begins with a black screen and the sound of a telephone ringing. A man answers. “Hello?” But, there’s no one on the line. The man repeats his 'hello' half a dozen times, his voice getting sillier each time. His last 'hello' sounds like the assertion of a slightly annoyed carnival barker and seems to set off a dizzying, newsreel-style animation. In one sequence, an actress runs through a range of emotions in front of a picture of Shakespeare as if she doesn’t quite know how to respond to history. In another, images of Karl Marx and Joseph Stalin seem to be interlopers in a Victorian-looking parlour. We hear from the Former British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain who tried and failed to broker peace with Hitler. A Lincoln Continental floats underwater. Playing the proverbial big fish, it opens its grill and eats a smaller fish. Later, Che Guevara is depicted emitting a fiery speech bubble. Through these accumulated collage sequences, VanDerBeek seems to ask who is there on the other end of the line, holding a moral compass when needed, keeping track. Without accountability, perhaps all we have to define ourselves is travesty and farce.

Coming across works by Stan VanDerBeek is like finding an unclaimed leather jacket at the back of one’s closet, a ready-to-wear statement piece with history. VanDerBeek was prolific, a free radical and a nonconformist. As a student at the iconic Black Mountain College, he was in the audience for the first, disciplinary-breaking Happening in 1952. He was an artist-in-residence at television stations and for NASA. His experimental impulses echo the spirit of the times in which he came of age. The great critic Susan Sontag, in her writing about the 1960s, described the era’s sensibility as sped-up, conscious of history, and equally concerned with film, art, popular music, and machines.

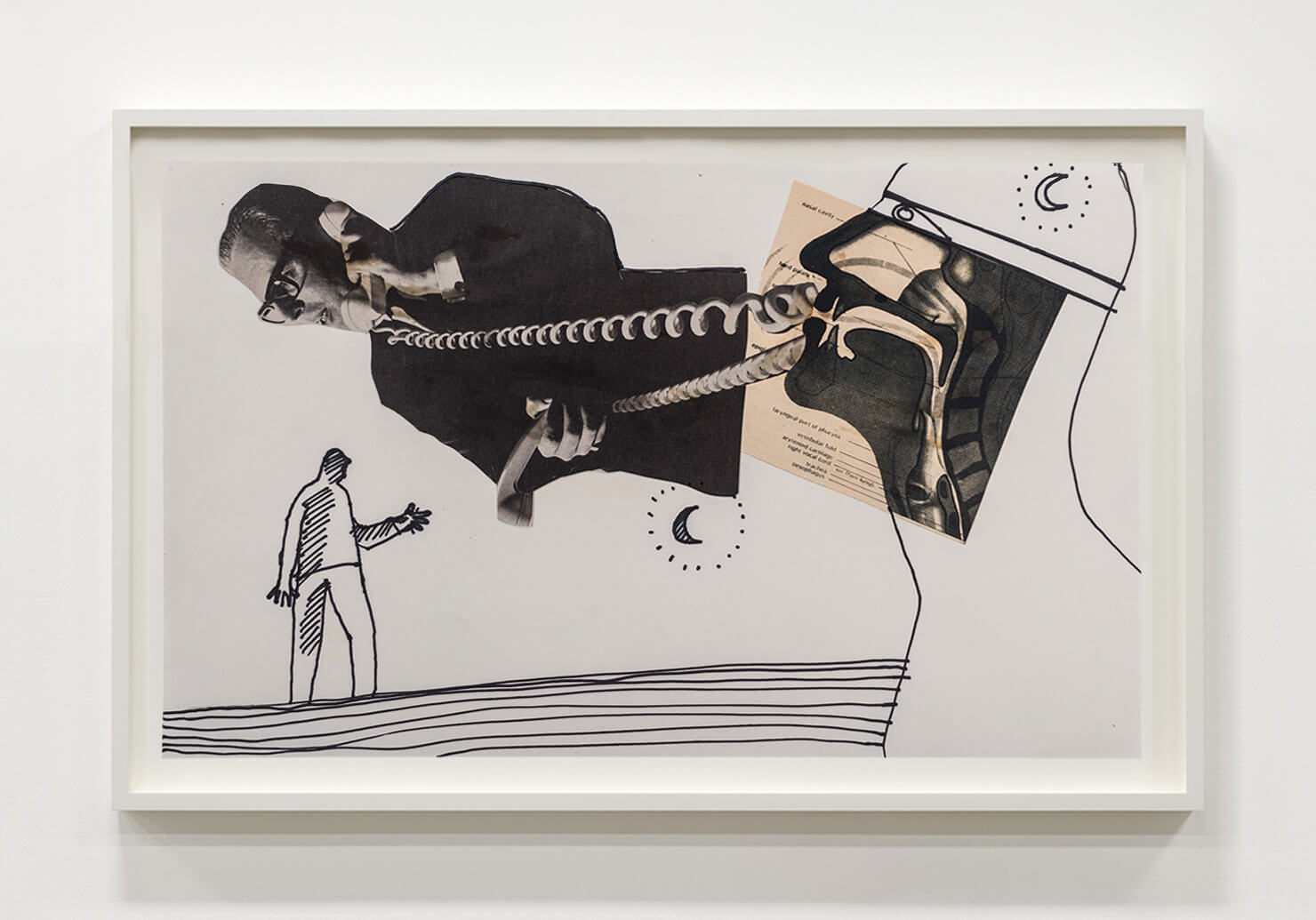

Maybe what I was picking up at Magenta Plains was something more like leather perfectly worn-in, or a dogged belief in humanity despite its evident failings. Throughout the gallery’s rooms are framed collages and drawings, most about the size of a standard sheet of office paper. One Untitled drawing from 1965 shows a legion of nude men lined up and smiling, perhaps ready for a skinny dip as the day begins. On the other extreme, an Untitled collage from 1964 presents a woman with a fork in her eye.

A smaller exhibition at the same gallery last year showed three of VanDerBeek’s films on a continuous loop, billing them as surreal and edgy “distillations of the complex and raucous zeitgeist of the early 1960s.” After all, this is the period that saw the first televised presidential debate, the first man in space, nuclear brinkmanship, and significant struggles for equal rights on planet Earth, not to mention the ongoing American War in Vietnam, despite its staggering civilian and military death toll.

When he died of cancer at 57 in 1984, VanDerBeek left behind stacks of art. In his lifetime, he imagined and demonstrated novel ways to disseminate his work. As he protested perpetual war, he also advocated for new media. In 1970, he named “the computer” the new talent to watch in an issue of Art in America, and predicted in the magazine’s pages, “Art schools in the near future will teach programming as one of the new psycho-skills of the new technician-artist-citizen.” He built a prototype for what he conceived of as a series of Movie-Drome or “experience machines,” low-slung, nook-like screening room domes. One of them was reconstructed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York last year for the exhibition Signals: How Video Transformed the World. Inside, projections overlapped. Being inside felt like occupying the world’s retina, an eyeball on our culture.

VanDerBeek also realised paper murals he’d share tile by tile through proto-fax machines for other people to install at multiple locations simultaneously. Magenta Plains has scores of the collages that were eventually faxed and some of the faxes too, which has allowed them to re-mount a fax mural in their main gallery. Titled Panels for the Walls of the World: Phase II (1970), at its centre, are images from magazines of guns, soldiers, and bomber planes cut out and glued in tight formation with more prosaic images like ones showing a typewriter, a paint tube, and Paul McCartney with his family on a 1969 cover of LIFE magazine. Everyone and everything is stuck in close proximity to instruments of violence and war.

Despite VanDerBeek’s enthusiasm for progress, he wouldn’t give himself, or us, over to brutes. He was an amusing and concerned broadcaster, a machine man with a human heart. On view in the basement gallery at Magenta Plains, his ten-minute film Oh (1968) employs stop-motion animation. The soundtrack seems like it could have been made by tigers loose in a drum shop. We see a hand emerge from a human mouth. There are bandaged, bloody, and drowning heads, full human forms scratched out of wet paint, and a face-off between two figures that results in both soon looking like visages made out of intestines—beautiful, gruesome, agitated, eerie and then gone.

'Stan VanDerBeek: Transmissions' is on view at Magenta Plains until May 4, 2024.by Hili Perlson Sep 26, 2025

The exhibition at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus unpacks the politics of taste and social memory embedded in the architecture of the former East Germany.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 25, 2025

At one of the closing ~multilog(ue) sessions, panellists from diverse disciplines discussed modes of resistance to imposed spatial hierarchies.

by Mercedes Ezquiaga Sep 23, 2025

Curated by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, the Bienal in Brazil gathers 120 artists exploring migration, community and what it means to “be human”.

by Upasana Das Sep 19, 2025

Speaking with STIR, the Sri Lankan artist delves into her textile-based practice, currently on view at Experimenter Colaba in the exhibition A Moving Cloak in Terrain.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Marcus Civin | Published on : Apr 14, 2024

What do you think?