Jackfruit processing plant by atArchitecture empowers farmers in Meghalaya, India

by Bansari PaghdarApr 28, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Dhwani ShanghviPublished on : May 16, 2024

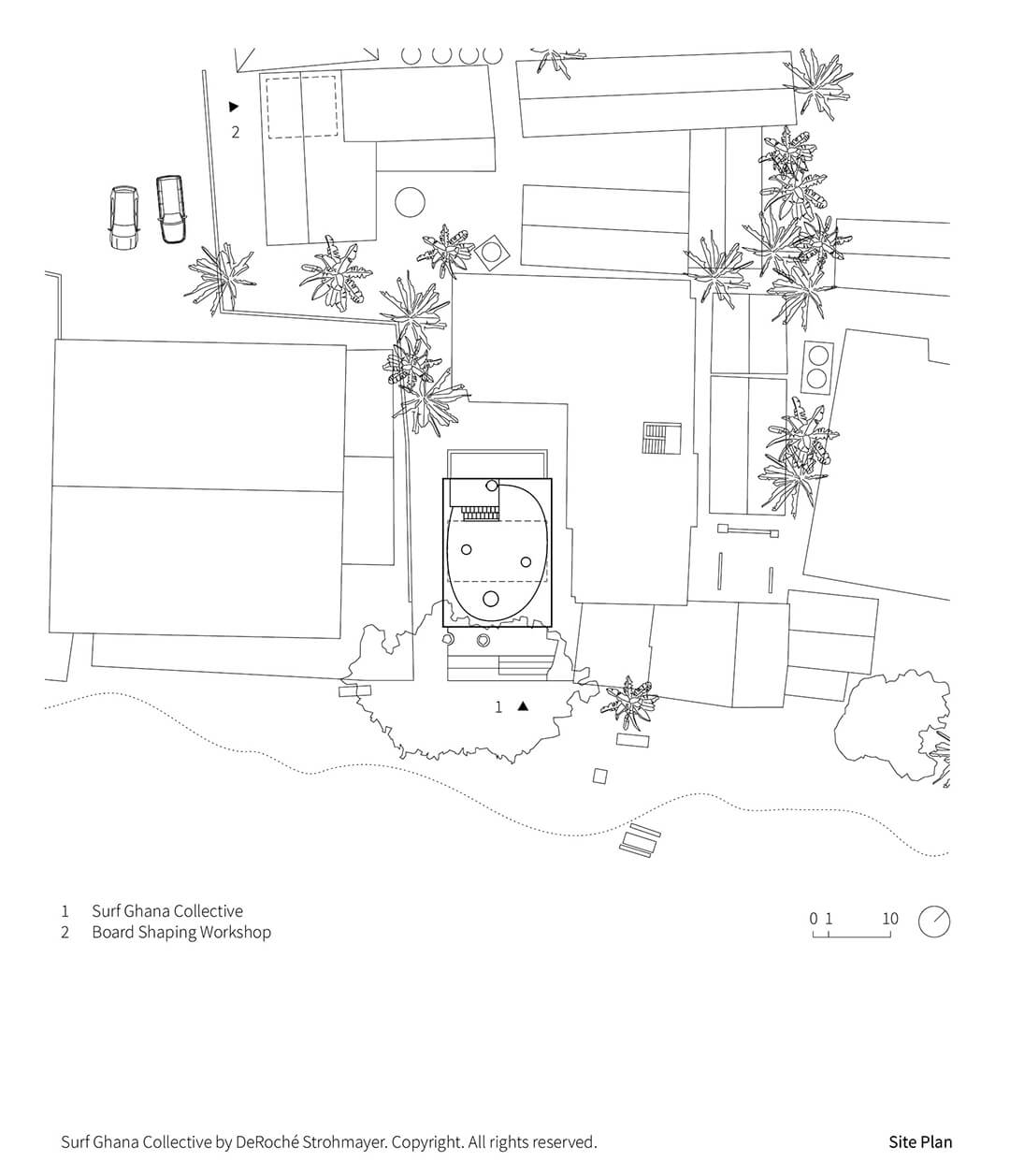

Along the coastline of Ghana's Western Region, in the fishing village of Busua, the Surf Ghana Collective, a non-profit organisation, appropriates an existing surf club with a new plug-in, in the form of an expanded canopy and sculptural columns. Central to their vision is a dynamic community space facilitating communication between the surfers and locals, by mobilising access to a growing culture of surfing as a sport.

Designed by DeRoché Strohmayer, the intervention is a cohesive blend of Busua’s local context and Ghana’s contemporary built environment, resulting in a seamless integration of the existing with the new, while simultaneously expanding the programme through the introduction of a terrace on the canopy’s rooftop.

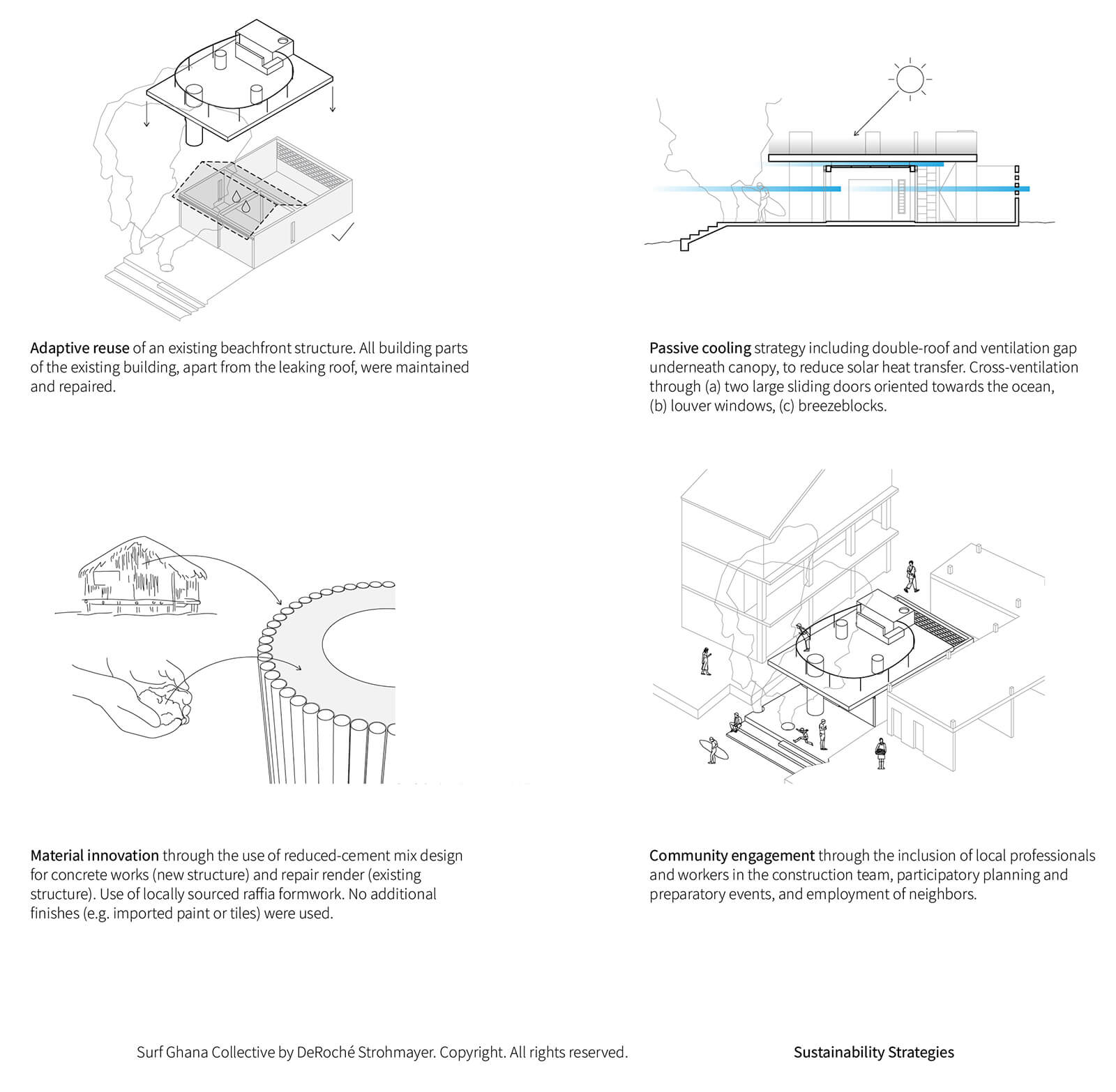

Employing a grassroots approach to building, the African architecture practice engages with local artisans as a means to augment local materials and construction techniques for sustainable construction processes. By creating a circular economy where resources and knowledge are shared, the project ensures that the community shares autonomy in its development, in addition to creating a collective social environment.

The Surf Ghana Collective project was awarded the 2023 Holcim Gold Award for Sustainable Construction, Middle East and Africa. In conversation with STIR, architects Glenn DeRoché and Juergen Strohmayer delineate the process of building a community space for collective and sustained engagement.

Dhwani Shanghvi: Can you introduce the studio and your team, particularly concerning previous projects or experiences that have influenced your approach to the Surf Ghana Collective project?

DeRoché Strohmayer: DeRoché Strohmayer is an architectural practice based in Accra, New York City, and Vienna. The studio realises responsive, relevant and enduring projects that are rooted in their context through the design of meaningful, forward-thinking and inclusive spaces. Guided by creativity and curiosity, the studio’s projects are often led by research and community-focused engagement. Since establishing a base in Ghana and engaging with public architecture locally, we have noticed that a sense of community or public space has been lacking. We have been struck by the ironic nature of recently built “public” buildings that do not offer any publicly accessible space. Additionally, seeing so many buildings that mimic Global North typologies brings up the question of how architecture garners its identity from its environment, geography, local lifestyles and available resources. This question has led to the design of the Surf Ghana Collective, through which we have endeavoured to create an engaging space along the Western Region coastline that is sustainably responsive, ingenious in local material exploration and community-oriented.

There’s an openness, expressiveness and dynamism in Ghana’s (self) built environment that we also felt compelled to capture in this design.

Dhwani: How did you conduct research to understand the local context and culture of Busua?

DeRoché Strohmayer: Our research for this project started as a visual documentation of the coastline architecture of the Western Region of Ghana, where the site is situated. We knew we wanted to make a unique project but still held qualities that would assimilate the building into its local context. We came across the beautiful visual continuity of the reeds that clad the Nzulezu fishing village nearby. While we are not driven by mimicking these vernacular forms, they inspired the textured finish we wanted to achieve for the project. Our research then moved from formal and textural studies to more pragmatic research, such as what was achievable to build within the low-lying coastal town—much of which is made up of self-built buildings. Understanding the limitations in this regard helped create a set of guidelines to manage the design, ensuring buildability through the calibre of workmanship that was available to us in the region. Our research also extended into the programmatic planning of the space. While observing the contemporary culture along the coastline, we noticed multiple user groups that exist beyond the surfing community. These different user groups make up the dynamic culture of Busua. Within this research of the different group typologies that meander up and down the coast, we wanted to ensure that we would make a space that would welcome all members of the community to engage with it. Essentially, the Surf Ghana Collective House is made with surfers in mind but also serves the community as a whole—from the local children who enjoy the beach after school to the women who take breaks from selling produce along this vibrant coastline.

Dhwani: How does the design of the new canopy and pillars reflect the sculptural qualities of the contemporary built environment along Ghana’s coast?

DeRoché Strohmayer: Having worked in and studied the built environment of coastal Ghana for more than a decade, we have cultivated a multi-layered, nuanced appreciation of its qualities and histories. We want our projects to also question the status quo, so our approach to formal referencing is multifaceted. This contextual sensitivity and avant-garde quality in our work has yielded rewarding results in the case of the Surf Ghana Collective project. Building a visual marker on the coastline, perhaps of a similar scale and visual appeal as the exuberant Fante shrines further east, was important for us, as the structure is meant for the youth of this fishing village. Our architectural intervention—a multifunctional roof slab that spans over an existing building, supported by figural columns—evokes the dynamism of the surrounding built environment. The columns on the roof terrace terminate and allow for functional interpretation. Similarly, neighbours build their structures in stages and columns can be seen that are ready to be integrated in the next building phase. They are often temporarily used to attach shading devices, hang hammocks, or support other commercial or leisure activities. There’s an openness, expressiveness and dynamism in Ghana’s (self) built environment that we felt compelled to capture in this design.

The rawness of the existing architectural fabric along the coastline of the western region can be seen as a stretch of informal, rough structures, but we saw it for its honesty—a kind of honesty that allowed us to accept the outcome without aiming for remedial works and dressings, which is often used by architects as a way of covering up blemishes.

Dhwani: The use of raw concrete texture and local materials like raffia palm formwork seems to be a conscious effort to blend the project into its oceanfront environment. How do they relate to Busua's architectural and environmental context?

DeRoché Strohmayer: The material palette for the project was born out of consideration of the local availability of materials and their longevity, efficacy and design. Raw concrete proved to be the best material as it met all of our criteria. However, we didn’t just want to work with a normal concrete mix, understanding the effect its off-gassing has on our environment. We, therefore, worked on creating a more sustainable, low-carbon concrete mix design that uses finely sieved earth from the region as an additive to minimise the amount of cement required. This reduction in cement resulted in minimising the amount of CO2 released by the structure as the concrete cures to its full strength. The outcome was a naturally pigmented concrete that echoes the sand colour of the beach. Additionally, rather than using typical formwork, which is imported and costly, we opted for a more creative and sustainable solution—the use of raffia reeds. This allowed us to minimise our carbon footprint by reducing the number of imported materials that needed to be transported, which also resulted in a biodegradable formwork as it is made from a natural material. This resulted in a fluted texture that not only became a beautiful ode to the vernacular architecture in this region but also allowed us to distinguish the newly added elements from the existing ones in this adaptive reuse project. The rawness of the existing architectural fabric along the coastline of the western region can be seen as a stretch of informal, rough structures, but we saw it for its honesty—a kind of honesty that allowed us to accept the outcome without aiming for remedial works and dressings, which is often used by architects as a way of covering up blemishes. It is exactly these ‘’blemishes’’ that give the architecture a distinct character and also allow it to seamlessly blend into the existing context.

Dhwani: Considering the economic sustainability aspect of the project, how did you ensure that the design and construction processes provided opportunities for local community members or artisans to participate or benefit?

DeRoché Strohmayer: Given the project’s geography, involving the community was inevitable for us and impactful for the project. The majority of formal skill sets reside in the capital city of Accra. Typically, contractors are transported from Accra to other parts of the country to build large-scale projects with sizeable budgets. This model often leads to a lack of skillset transfer and an edifice that is devoid of community input or does not offer any job opportunities. While we opted for a formal contractor from the nearest large town, Takoradi, we intentionally engaged local resources from Busua for the project, ensuring an exchange of building knowledge and skillset transfer. This added to the economic sustainability as many of these workers were already living in the town and financial resources were not required to provide housing as is typically done for workers coming from outside. Throughout the construction process, we were frequently present on site, which was good for overseeing the quality level and answering questions from passersby who were curious about what we were doing: Why were we using the raffia reed this way? What was the material we were plastering the outside of the building with? Combined with providing answers to the community, spending time on site allowed us to observe and be inspired by the craftsmanship of the boat builders on the coast. This inspiration led to the design of the furniture within the space, for which we utilised boat-building techniques to detail the assembly of the furniture range made for the project. Working alongside these artisans on the design and construction of the timber furniture was inspiring and left us curious to explore more artisanal ways of crafting bespoke items.

Dhwani: The Surf Ghana Collective is a dynamic community space for Busua's youth. How did you envision this space fostering social interaction and community engagement within the context of the fishing village?

DeRoché Strohmayer: Busua is known for its vibrant social scene and the residents of this town have a strong water connection, whether it is through fishing, surfing, or casual frolicking in the shallows. With reduced access to paved pedestrian walkways, the primary road is typically used for vehicular traffic, while the beach has become a major thoroughfare for pedestrian movement. Observing these conditions, it became evident that the threshold between the beach and the building was important to consider in terms of bringing the community together. The design resulted in creating a multi-tiered seating platform facing the ocean that doubles as an amphitheatre for community activity and a place of rest. In addition, the one-room social space opens half its oceanfront elevation towards the beach, forming an inviting aperture into this social hub. By creating an open and socially driven interface to the beach, the building naturally becomes a beacon for social engagement. Another successful design element that draws the community into the space is the internal courtyard at the rear of the building. This is not typically seen as many beach properties prioritise maximising their built footprint. The natural light emanating from this open-air courtyard moves users deeper into the space to realise more of the building programme, as does a set of stairs that leads to a roof terrace. This roof terrace has become a nexus for hangouts, open-air movie nights, barbecues, etc. It has been rewarding to see how the community has made use of a space that was openly designed for their imagination.

Dhwani: Can you share any challenges or constraints you encountered during the contextualisation process and how you addressed them?

DeRoché Strohmayer: The goal for the project was not to make a building that was directly contextualised with the seaside setting. This would have been very difficult as there is a vast difference in character when it comes to the building typologies and forms that make up the coastline in this western part of Ghana. Typically, one approaches contextualisation through the lens of assimilating by means of replicating common formal characteristics. We decided to invert this way of thinking and look at contextualisation as a celebration of difference and an addition to the pool of variety as the common thread with our neighbours. This way of thinking led the design process and resulted in the thoughtful, modern form that makes the Surf Ghana Collective House. Although it is unique in form, many of the same tropical architecture principles are prevalent here but articulated in different ways. For example, instead of the commonly used pitched roof with large projections, we created a flat slab with overhangs to protect the building from the heavy seasonal rains and sun. This flat roof not only provides the same protection as the typical pitched roof seen along the coastline, but by making it accessible, we have also increased the amount of useable floor available for the public. In celebrating differences as a form of contextualisation, we moved away from using the bright colours that pepper the coastline structures and opted for a monotone colour approach which draws its inspiration from the colour of the beach sand lying at the foot of the site. As a practice, we always challenge ourselves to approach constraints as opportunities for innovation within the design process to achieve a better-contextualised response to a client’s brief.

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 16, 2025

For its sophomore year, the awards announced winners across 28 categories that forward a contextually and culturally diverse architectural ecosystem.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Dhwani Shanghvi | Published on : May 16, 2024

What do you think?