Christopher Kulendran Thomas' art bears the scars of Sri Lanka's civil war

by Manu SharmaNov 04, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Manu SharmaPublished on : Dec 22, 2024

Tate Modern in London is currently presenting Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, a monumental group exhibition of over 70 artists who worked between the 1950s and the early 1990s (culminating in the internet boom of 1994) - all pioneers in experimenting with new technologies during that time. The practices featured in Electric Dreams include early artificial intelligence (AI) developers like Harold Cohen and Eduardo Kac, who looked at digital networks as both production tools and distribution platforms, and some of the first generative artists, such as Vera Molnár. The show is on view from November 28, 2024 – June 1 2025, and is curated by Val Ravaglia, curator, displays and international art, Tate Modern, with Odessa Warren, assistant curator, international art and Kira Wainstein, research assistant. Ravaglia joins STIR for an interview that looks back at some of these pioneering practices and contextualises them in relation to the major conversations unfolding at the intersection of tech and art today.

Ravaglia mentions that when conceptualising Electric Dreams, she did not wish to include artists who were concerned with digital networks as social platforms. However, this raises questions surrounding the inclusion of Brazilian artist Eduardo Kac. Kac used Videotexto, an interactive videotex online service, to create and distribute ‘digital poetry’, like Reabracadabra (1985).

I don’t think any of the artists included in the exhibition worried that automation could ever replace human creativity. After all, photography had not killed painting or illustration, despite the protestations of many. – Val Ravaglia, curator, international art, Tate Modern

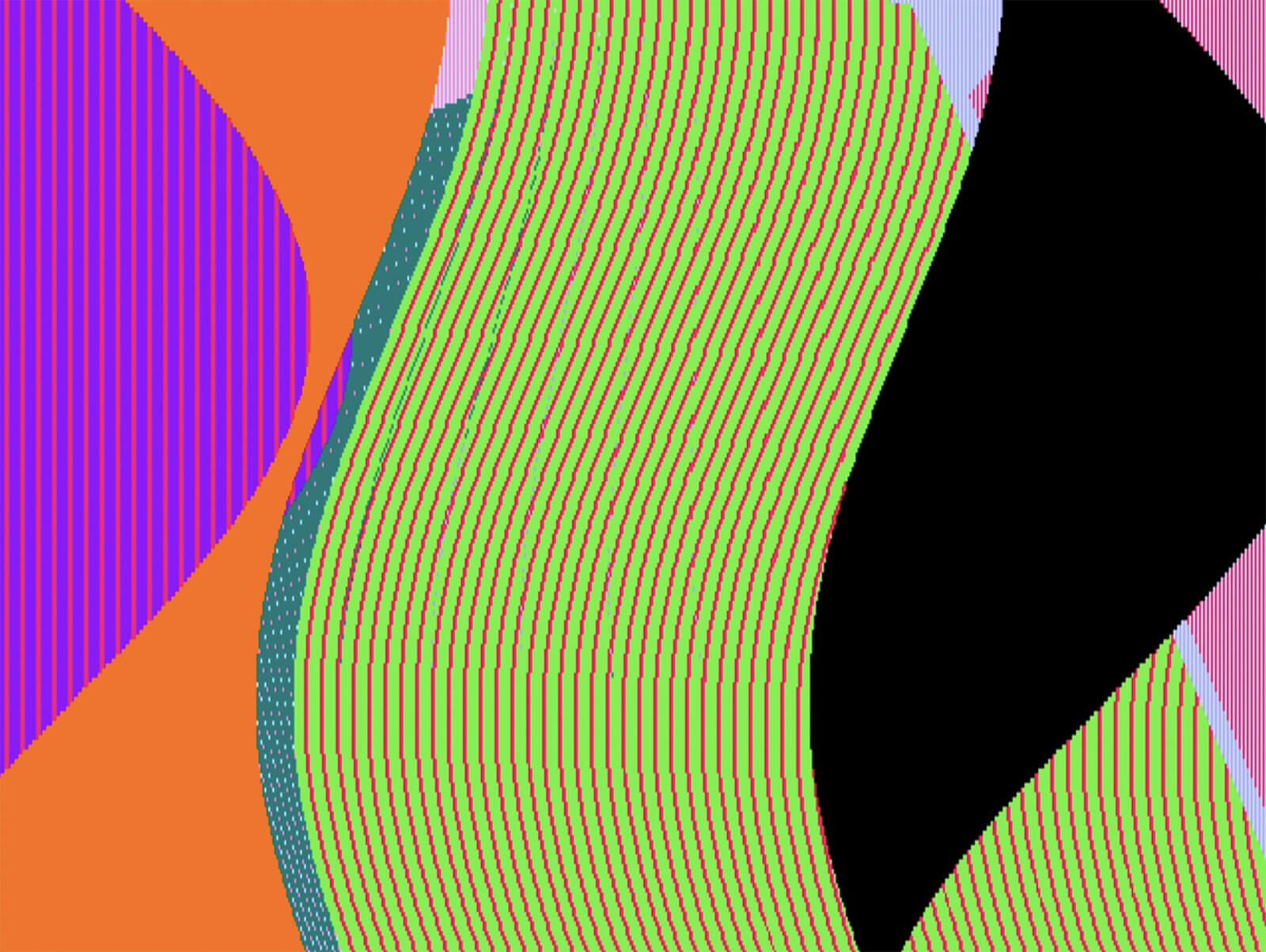

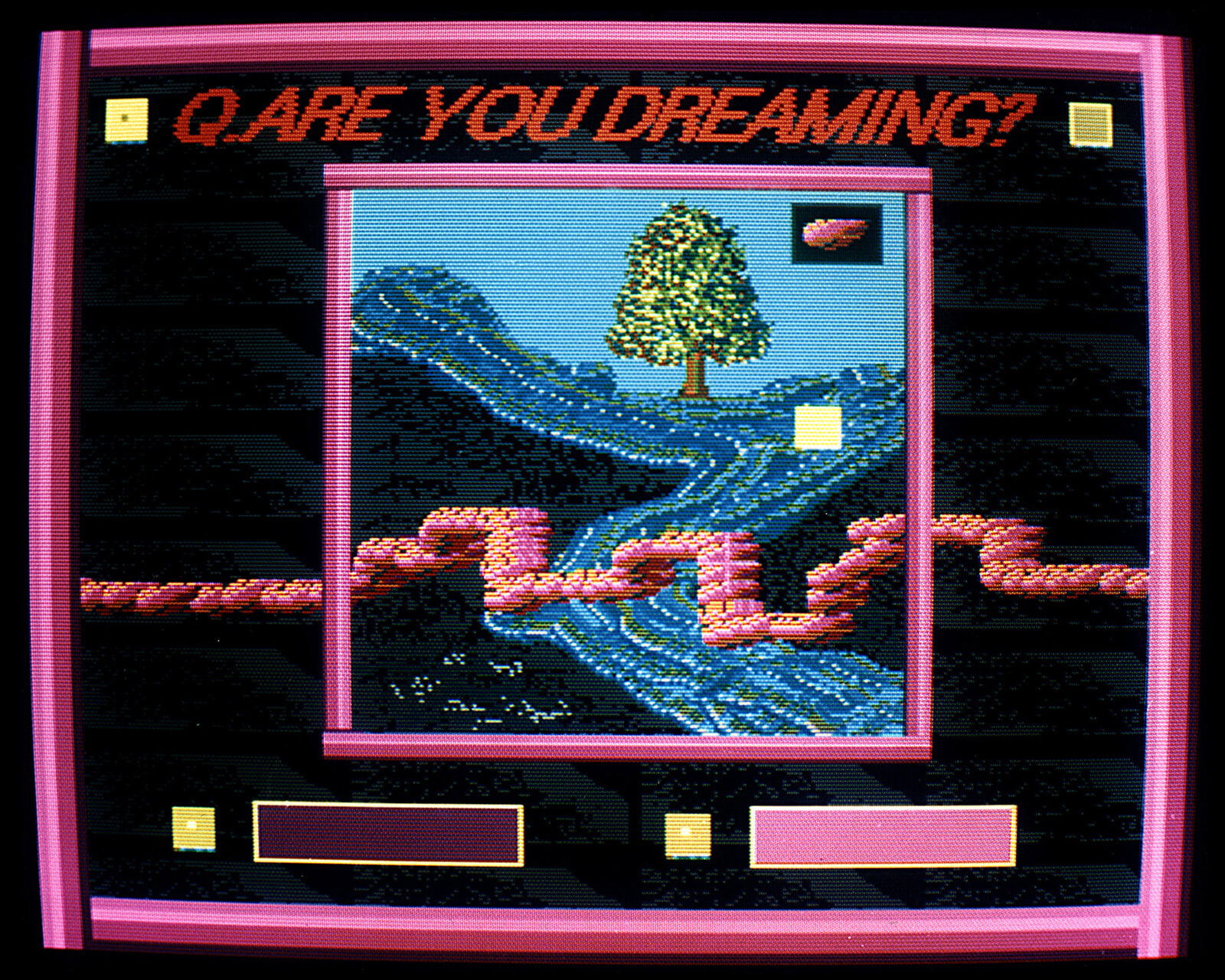

The open network Minitel was prevalent in the 1980s and 1990s, and provided various services we associate with the internet today, such as a mailbox and chat. Videotexto began in Brazil in 1982, with its popularity peaking at around 70,000 users in 1995, right as the commercial internet began. Works by Kac, such as the Reabracadabra, used Videotexto’s text and image-generating functions to create animated digital art that is somewhat reminiscent of Windows 95 screensavers, as well as images created using the Logo educational programming language. These would then be viewable by audiences who were using Videotexto stations.

Ravaglia discusses Kac’s inclusion in the show, telling STIR, “I made an exception for Eduardo Kac’s Minitel works, partly because they functioned more as media insertions than as social projects: they used a new mode of distribution that was a direct precursor to the internet, but more as a novel broadcast method than as a social medium.” What is key is that Kac did not consider the incorporation of his audience’s responses into his artmaking at the time.

In light of contemporary worries around artificial intelligence diminishing human agency in artmaking and other fields, one may wonder how these early creative adopters of digital technology viewed the human element in the artistic process. In Ravaglia’s words, “I don’t think any of the artists included in the exhibition worried that automation could ever replace human creativity. After all, photography has not killed painting or illustration, despite the protestations of many. And the machines that artists were working [with] within the decades covered by this exhibition made artistic processes more laborious and intellectually challenging, not less.”

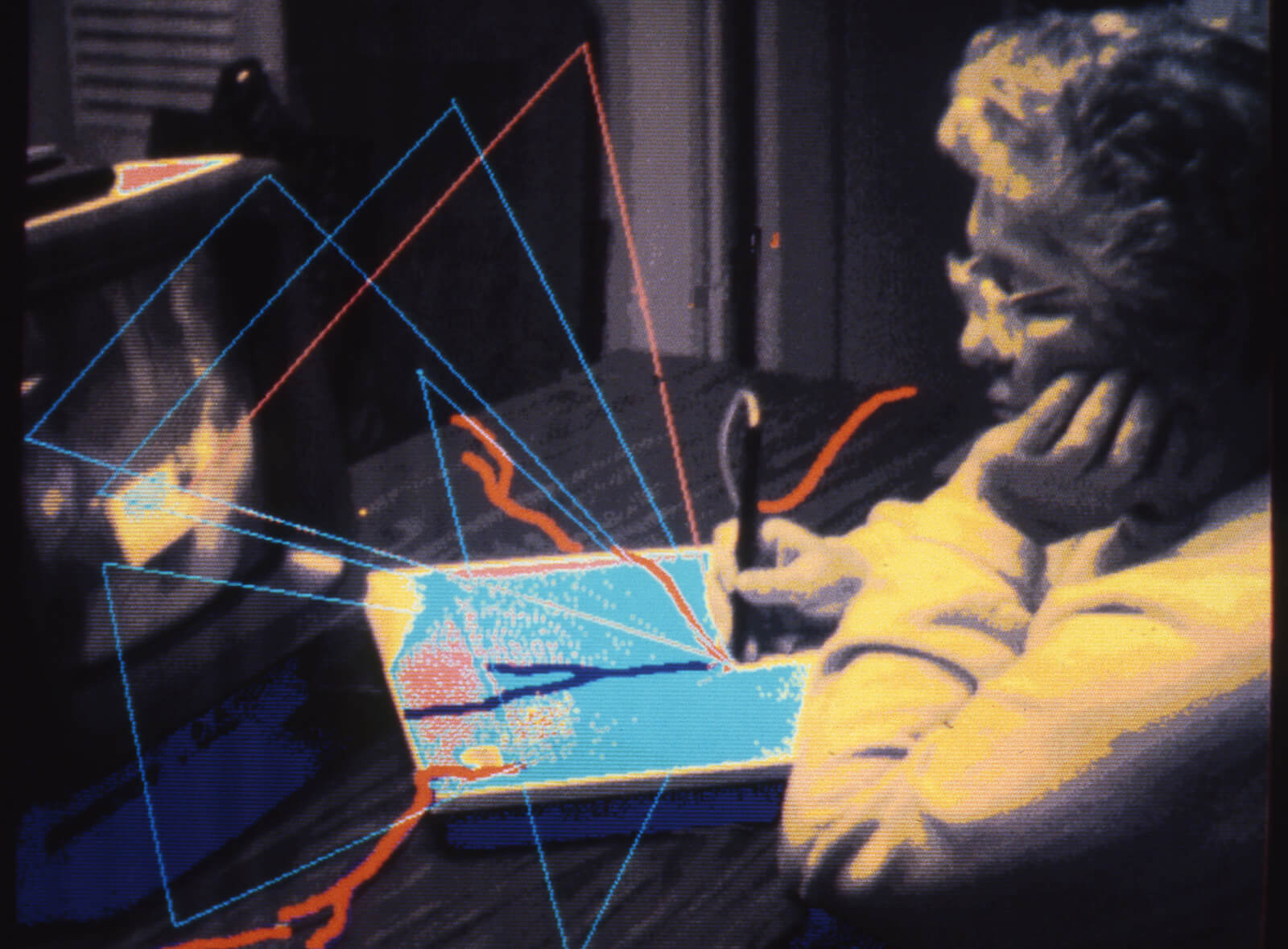

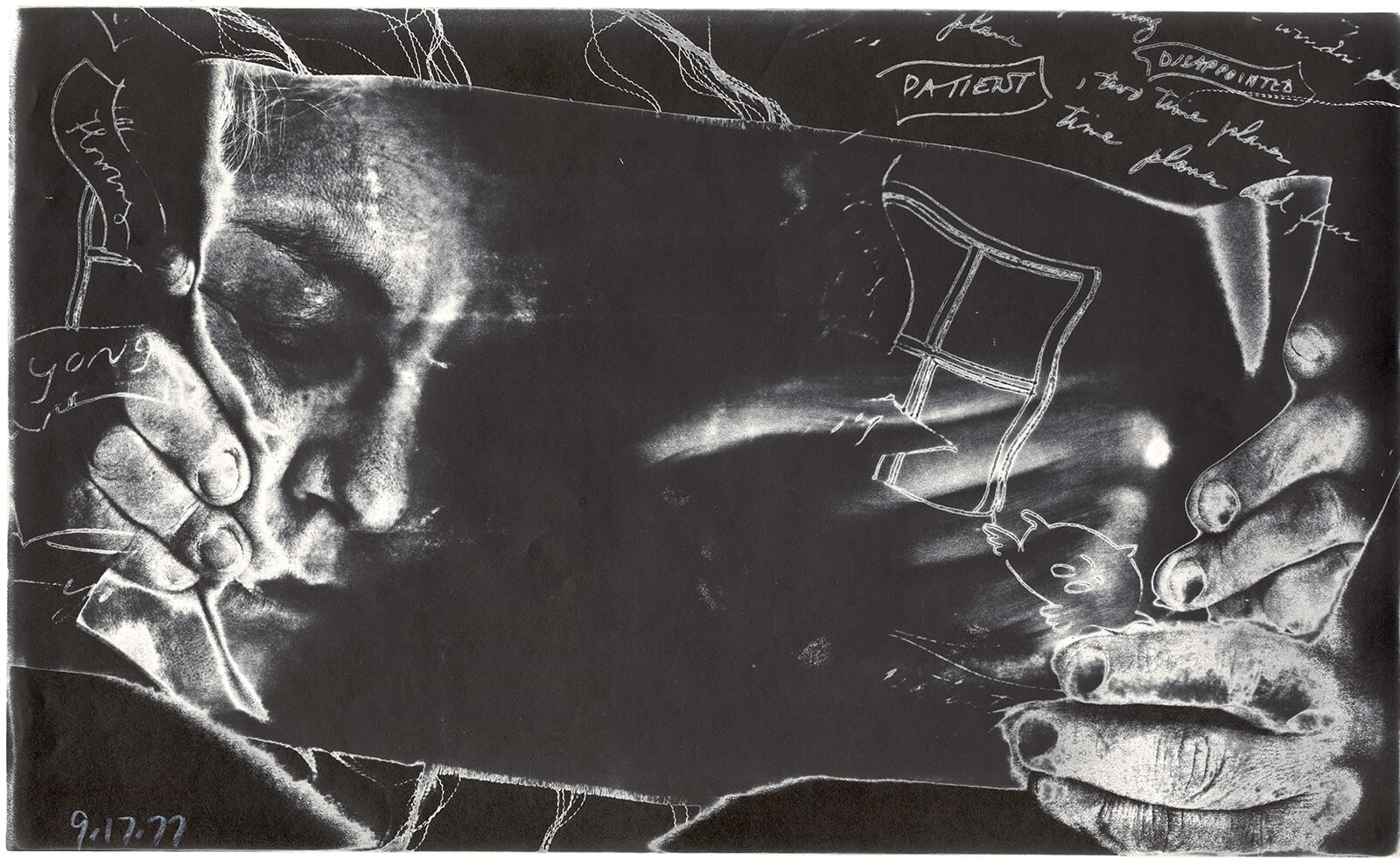

Ravaglia brings to our attention the work of Harold Cohen (1928 – 2016). Cohen developed the drawing software AARON, which is generally accepted as the first AI artmaking programme. However, this is not entirely true, as AARON did not have the seemingly limitless potential to learn that we see in cutting-edge AI today. Still, the software possessed a significant amount of agency to refine its craft within the parameters set by Cohen. Ravaglia tells STIR, “[He] was an accomplished and established painter already when he decided to learn how to code from scratch. He realised that ‘teaching a machine how to draw’ would be the best way to continue his investigations on image-making at large, on what makes signs legible to humans as meaningful images: it was an intellectual aspiration that moved him, certainly not a desire for expediency! Shifting to computer-generated images occupied him for decades and proved to be a huge setback on his artistic career, yet he persevered.”

Ravaglia believes that a core reason behind artmaking is the desire of artists to make sense of the world and express it, and as long as there remains something left to understand about the world, human beings will continue to create art. However, her faith in the preservation of human artmaking is not without an important caveat. She reminds us that photography puts many commercial artists out of business. It is as yet unclear if a similar chain of events will transpire due to the proliferation of AI art. However, we may very well see the digital artist community readjusting its processes to include AI in a manner that improves—rather than harms—their livelihoods.

Electric Dreams is a comprehensive primer on media art prior to the age of the internet. Moreover, it is a testament to the unbridled creativity and desire to experiment that unites the exhibited practices.

‘Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet’ is on at Tate Modern, London, from November 28, 2024 – June 1, 2025.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Manu Sharma | Published on : Dec 22, 2024

What do you think?