Art Jameel and theOtherDada imagine innovative interspecies structures into being

by Niyati DaveApr 05, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Feb 26, 2024

As much as architecture is a spatial practice, it is also a temporal one. Apart from the tedious processes of design and construction, involving countless intensive hours invested, practice recoils from questions of time and decay, in a way, the antithesis of building and architecture. Instead, the pursuit of a seeming permanence against the idea of a proverbial ruin drives nearly all technological innovation. This pursuit of a rather futile permanence, bolstered by modernist ideologies of acceleration and endless progress has led the current epoch towards conditions of resource depletion, the ongoing climate crisis, and the omniscient age of pandemics and natural disasters. This is the stance from which Lagos-based architect and curator Tosin Oshinowo curated this edition of Sharjah Architecture Triennial, on view till March 10, 2024.

Expanding on the theme for this year, The Beauty of Impermanence: An Architecture of Adaptability, Oshinowo’s curatorial note states, “Permanence has contributed to the climate crisis, as it has led to the construction of spaces using non-degradable materials, the extraction of resources without replenishment, and the design of buildings intended for single-eternal use.” What then, does it mean to talk about impermanence and the possibility of an ephemeral architecture? In thinking through the idea of temporality with the notion of the Kinetic City, Indian architect Rahul Mehrotra too builds on informal practices of spatial occupation specifically in India as counter to the assumption that permanence is a default condition to imagine urbanscapes. He writes, “Inherently temporary in nature, the Kinetic City is often built with recycled material: plastic sheets, scrap metal, canvas and waste wood.” Juxtaposing this idea of the permanent with the informal, transient structures and settlements for hosting massive gatherings, Mehrotra asks designers to consider the beauty in ephemerality in thinking of dwelling solutions that are not as resource intensive and account for constantly changing needs through multi-use spaces.

Thinking through the lens of impermanence and transitory architectures anchored in vernacular practices for Mehrotra signals a turn towards thinking with—the prevailing conditions of cities—in essence, thinking and devising in an area of deficit. Similarly, and by their very nature, nomadic and indigenous cultures, what Oshinowo calls the “undercelebrated traditions of the reason”, foreground temporality, the idea of decay, and above all, a concern for adapting to and working with the natural conditions, constructing a view of architecture from the fringes. In keeping with the idea of the impermanent and the fleeting by relying on a worldview that precludes the idea of scarcity, the architectural installations at the ongoing architecture triennial, in many ways, meditate on varied aspects of non-permanence in architecture, questioning what may be required to consider alternate ways of being.

In this vein, two of the installations at this year’s triennial especially highlight the idea of an architecture that embraces its transience and acknowledges the footprint they leave: the Jabala: 9 Ash Cleansing Temple by Olaniyi Studio’s designer Yussef Agbo-Ola and Time Transitions by RUINA Arquitectura which here act as sentinels, oscillating between questions of tradition, articulation, of what it means to construct, and what it means to live within spaces of flux. While the double tented Jabala: 9 Ash Cleansing Temple by London-based Yussef Agbo-Ola is an ongoing architectonic exploration of the ephemeral ritual practices of tribal communities from Asia and Africa, Brazil-based RUINA’s Time Transitions in the old Al Jubail market is a watchtower made of iron rods, and burlap to resemble scaffolding structures and an architecture forever in process.

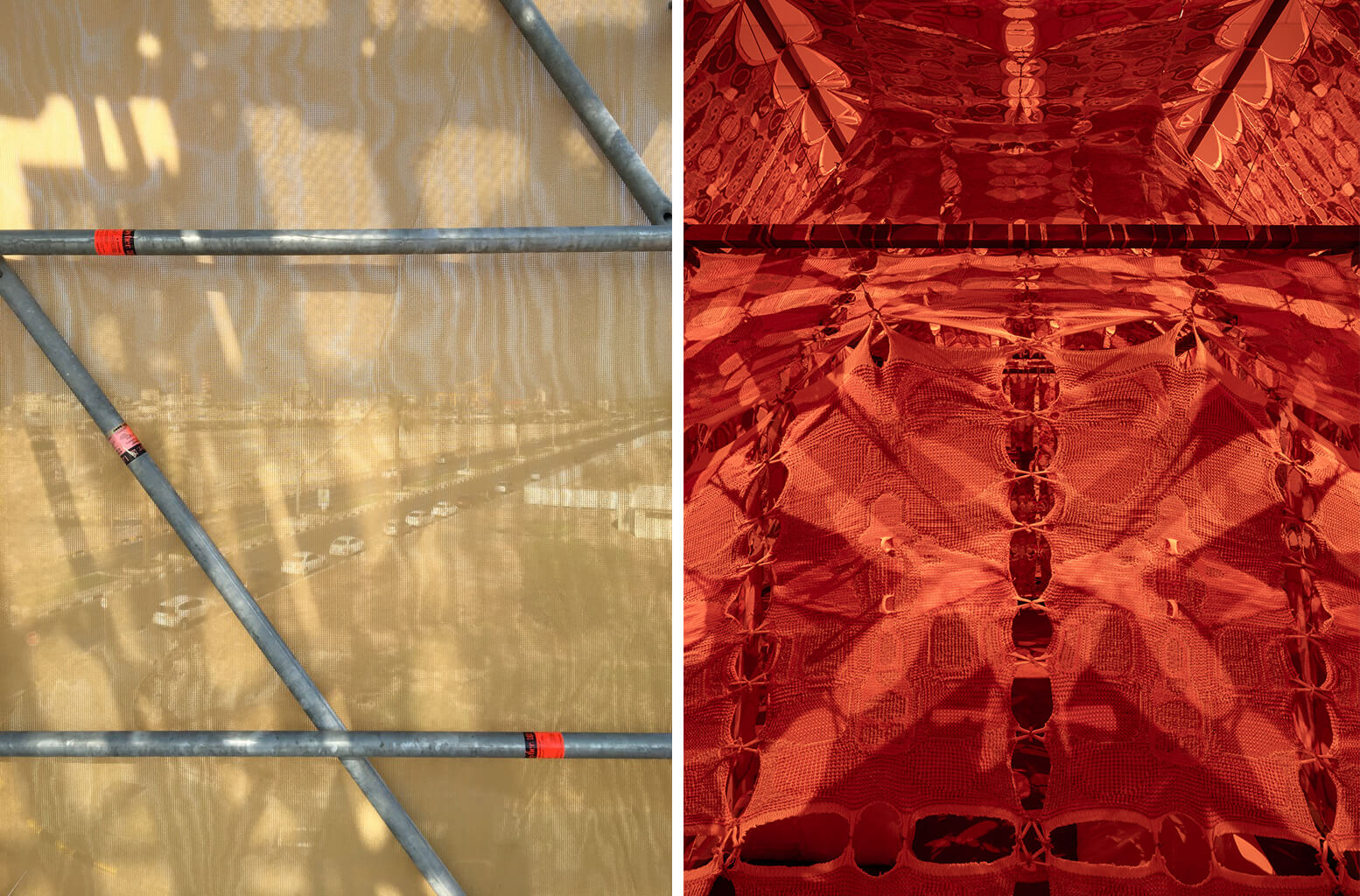

A sentinel to progress and the so-called modernisation of vernacular cultures, Time Transitions, the 18-metre-high installation at the entrance of the old Al Jubail Vegetable Market in Sharjah stands as witness to the transformation of the city, with the old market—built in 1980—now deactivated and facing imminent demolition while a new marketplace stands across the bank. Calling attention to the vernacular design of the old market, the structure asks one to pause. To that end, a formal reference for the installation also happens to be wind towers, a passive design technique employed for cooling buildings. The structure asks us to consider what development truly means, and what we lose in the name of progress.

As Oshinowo writes in Field Notes on Scarcity, a companion publication to the event, “We must acknowledge that we have been misled by the idealised narrative of machine-driven individualism and capitalism.” In underscoring the continual progress of cities by providing a crucial vantage point that juxtaposes the traditional market with the new structure across the bank, the scaffolding bears witness to the erasure of tradition in favour of technological innovation. Often, such an erasure also means the erasure of indigenous voices, such as with the displacement of tribal communities for major development projects.

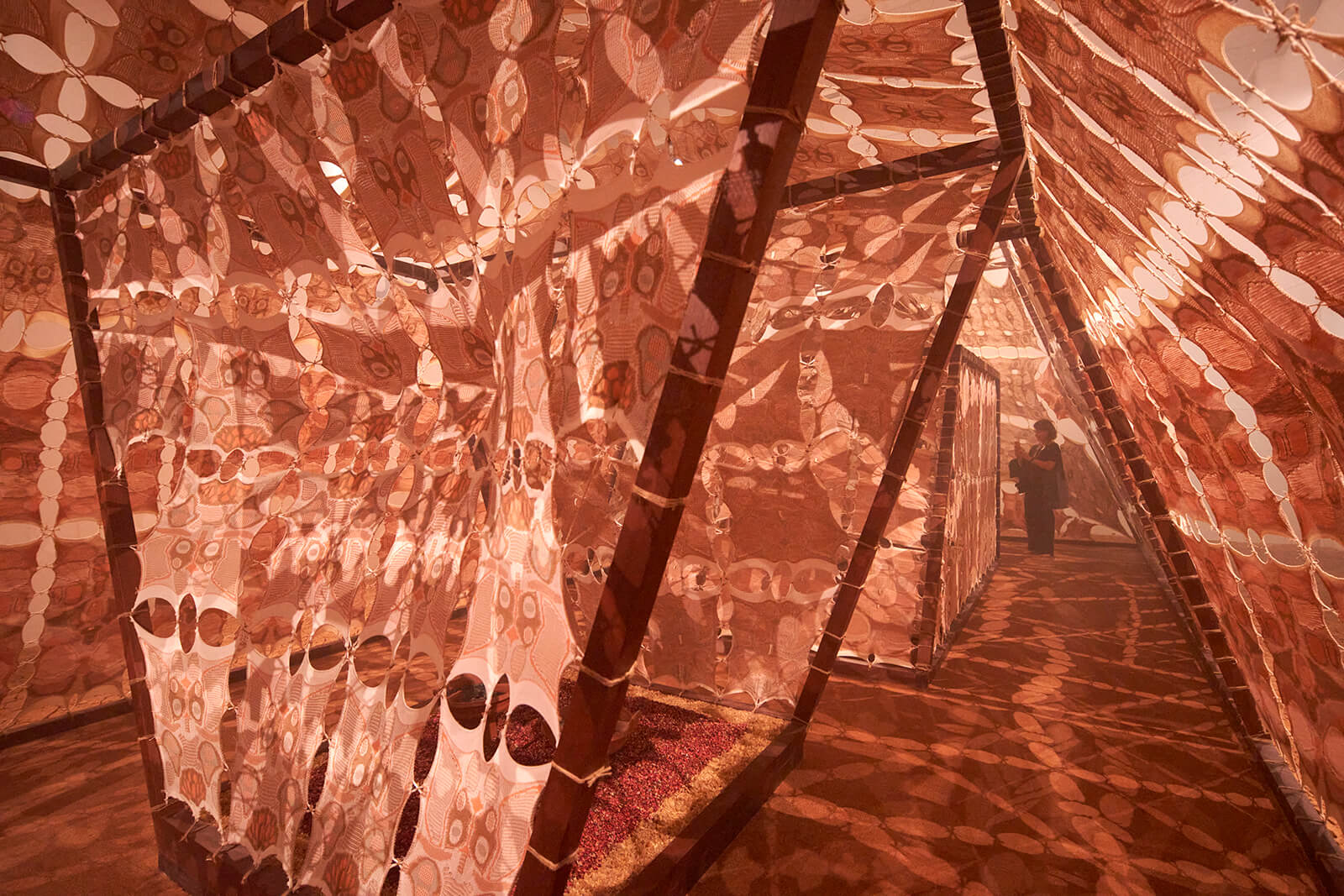

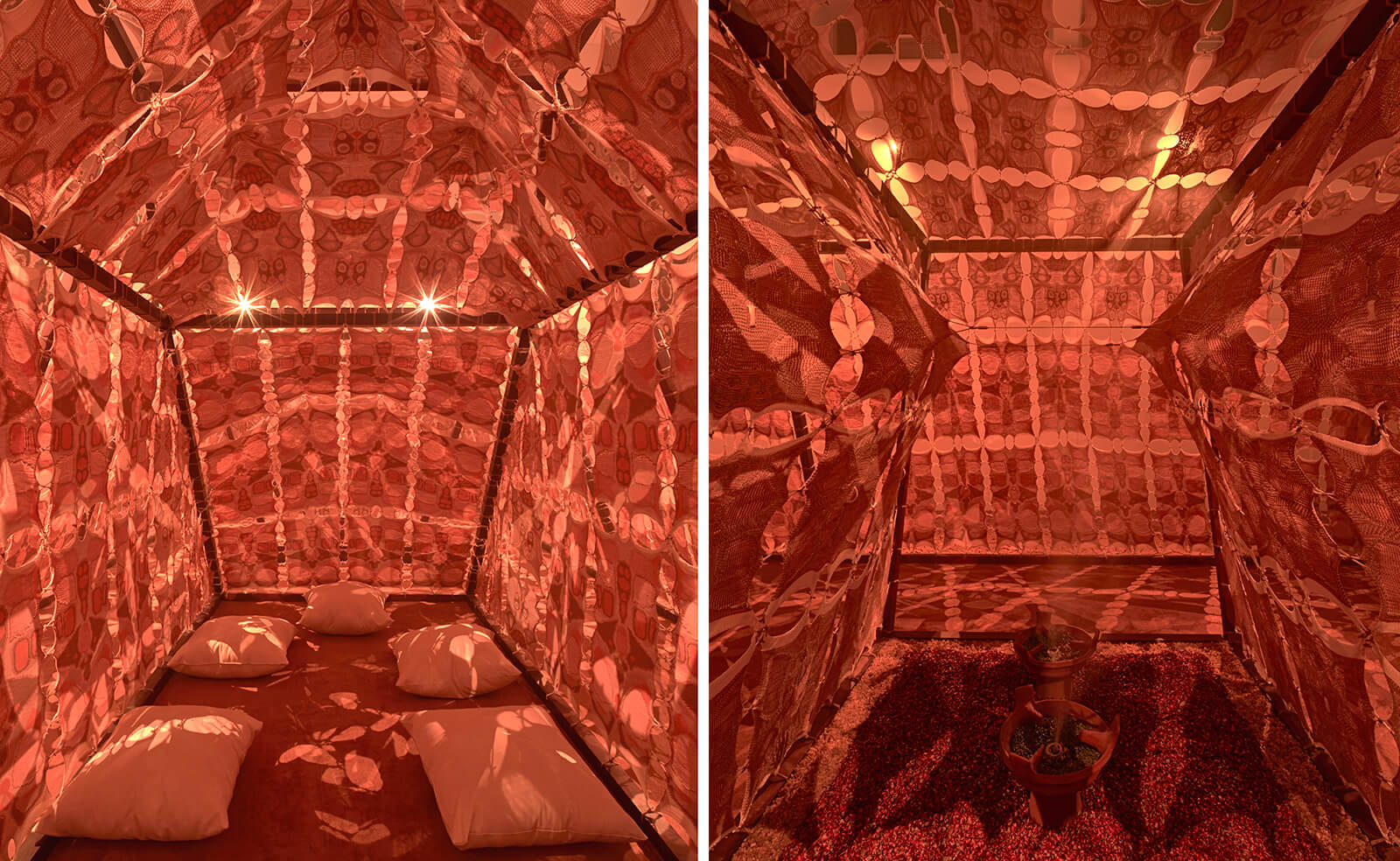

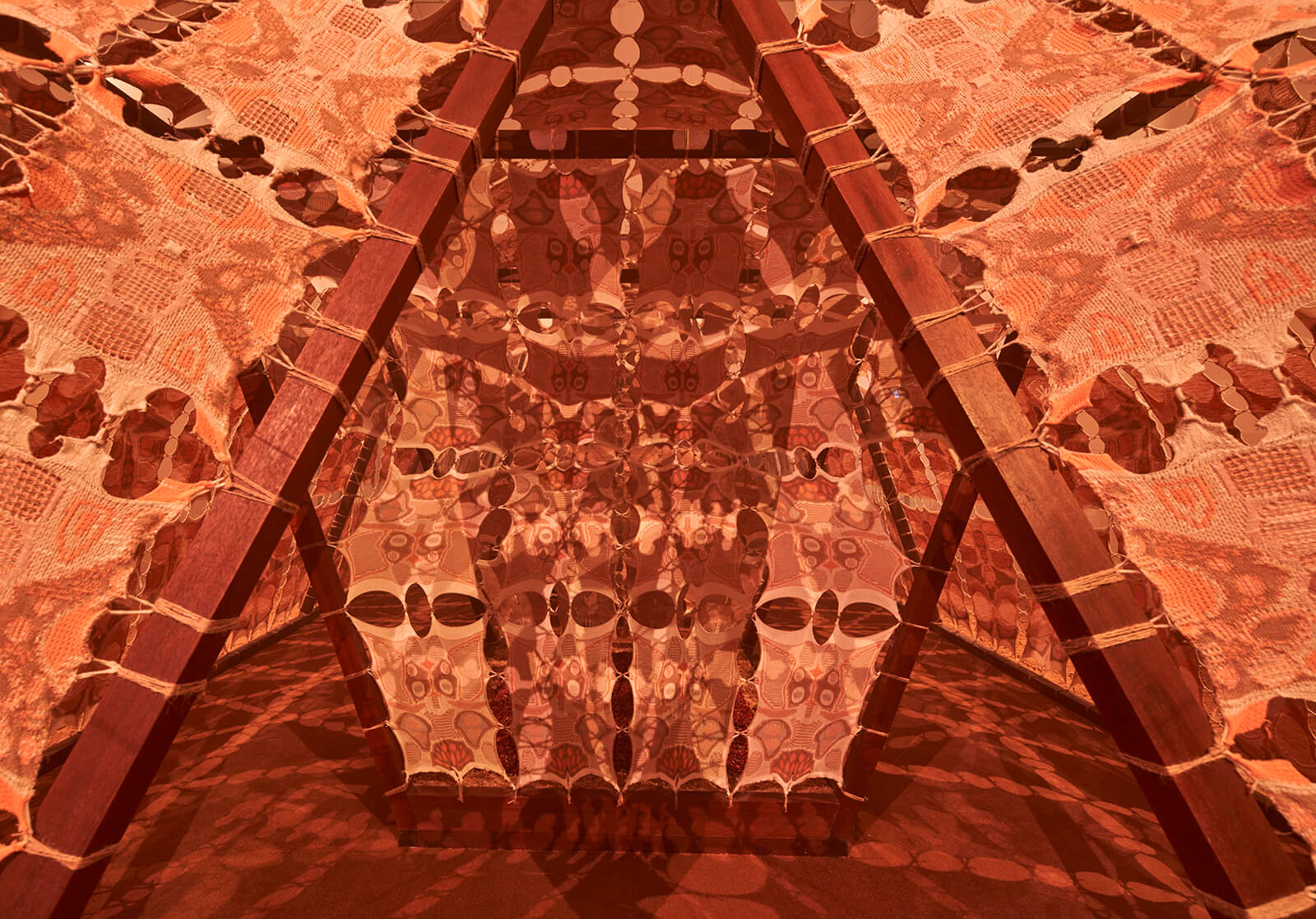

Taking the stance proposed by Time Transitions further, 9 Ash Cleansing Temple not only asks us to bear witness to the locus of culture, it proposes an architecture of planetary care by drawing out the relationship between the seen and unseen connections in our environments. The structure foregrounds the idea that humans cannot assert dominion over the environment endlessly but must work together towards a habitable future. Agbo-Ola calls on the silhouette of Ras Al Khaimah’s Jebel Jais Mountain as a design inspiration. Highlighting the interconnectedness of the man-made with the natural, he says, “It is my core belief that mountains are the mothers that hold an environment’s wisdom and DNA within them. They can speak to us and are seen as elements in a landscape that humbles us in relation to its scale and presence.” The tensile, liminal space of the temple, the bakhoor incense sticks, and the play of light and shadow work towards extending an invitation to the visitor to acknowledge that humans are active elements in a larger network within the biosphere and that we cannot survive alone.

The use of textile and tactile reference to tensile structures by Jabala: 9 Ash Cleansing Temple and Time Transitions allows one to dwell in the limbo between permanence and transience, formal and informal, the seen and unseen with their translucent surfaces. Both installations allude in some way to weaving and its long history in indigenous architectural practices in Africa and Central Asia through their choice of material. This use of textile could also be construed as a reflection on Gottfried Semper’s Four Elements of Architecture, and his argument about textile structures being architecture’s origin. Here, the tensile designs ask one to reimagine originary tales, prompting the imagination of an alternate future.

Explicitly referencing ephemeral rituals across architecture, performance, and art within the Bedouin, Yoruba, and Cherokee communities, the Ash Cleansing Temple calls attention to the interconnected networks of human and ecology, highlighting the care and respect of indigenous peoples for the natural world through their practices of environmental consecration. A negotiation of the cosmic and the material, the sacred structure acts as a space where visitors can immerse themselves in collective aroma rituals of bakhoor/incense burning.

Agbo-Ola further acknowledges the relationship between biodiversity and the built environment in his immersive installation through the individual fabric elements used in its façade design. Each draws from the skin of different plant and animal species that are endangered in the region, with singular motifs in the fabrics also reflecting cosmological belief systems within these cultures; symbols represent spirits, ancestors and environmental entities that human life depends on. The reliance on mystic imagery and the ritualistic nature of the installation further reinforces the idea of a return to the origin of architectural thought and a look to ‘primitivism’ for reference, questioning what it means for architecture that subsumes the natural.

On the other hand, the use of textile and scaffolding as the main ‘structure’ for Time Transitions directly alludes to the notion of degrowth. With the scaffolding and the burlap fabrics concealing and revealing, swaying in the hot desert wind, the structure becomes a symbol of thinking about the idea of transience in architecture, by suggesting an anticipation of completion that may never come. It becomes an architecture constantly in construction, while still dwelling upon the elemental, the basal aspects of the practice.

Ultimately, both installations are a meditation on an alternative future of architecture, an architecture that is born from need as opposed to aspiration, and responds to its place of being. In ruminating on the transience and impermanence of any architectural endeavour, they ask the visitor to practise caution, demonstrating the responses of acting from a space of scarcity. With RUINA’s work, the use of a scaffolding system was made due to its quality of quick assembly/disassembly and the almost endless possibility of reuse after the Triennial's conclusion. Demolition waste blocks were reused as counterweights, playing up the idea of decay. Working from this idea to explore impermanence and the need for adaptation, the installation also allows reflections on the meaning of regenerative architecture, envisioning alternative epistemologies that pay heed to what has come before, with the ruin acting as a guide.

While the purported death of tradition guides Time Transitions, the possibility of rebirth marks the Ash Cleansing Temple. The structure is designed to degrade and return, one day, to the soil or the forest, and will be transported after the Triennial ends to the Amazon. More than just its physical form, the structure instead engages in an act of near-mythical world-building that asks the visitor to reconsider where the structures we inhabit come from, and ultimately where they go.

The triennial which was born out of the prevailing conditions of inequality—of experience and resources—puts forth a prescient proposal for the future of architecture. And this future begins with asking the right questions. As Oshinowo stresses in her curatorial statement: “What lessons can be learnt from these autonomous self-organising systems that work within the limitations of the natural resources available? Can these systems be scaled to address our densification and curb carbonisation, in effect, planetary scarcity?”

Representing the primitive hut that could signal possible futures for architecture, we may further question: what does it mean to acknowledge the impermanence of structures?

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 12, 2026

The New Government Quarter by Nordic Office of Architecture reimagines the site of the 2011 terror attacks as a porous civic district shaped by architecture, landscape and art.

by Bansari Paghdar Mar 11, 2026

Conceived by Pentaspace Design Studio, this cuboidal volume of exposed concrete and glass pegs movement as integral to the learning experience.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 07, 2026

Designed at the threshold of cultural preservation and rapid urban growth, the museum references geology, history and cosmology to create a global tourist destination in Medina.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 05, 2026

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Bruce Goff: Material Worlds moves beyond architecture to reveal the curiosity and cultural influences that shaped the American architect’s work.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Feb 26, 2024

What do you think?