Metaverse Architecture and Design Awards 2023 unveils winners

by Pooja Suresh HollannavarJun 15, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Bansari PaghdarPublished on : Aug 07, 2025

A narrow hallway. A closed door at the end. Cables run across the floor and ceiling. On the walls? Advertisements. More cables. A vacuuming robot, observing the 'Observer'. The ‘tin man’ janitor unlocks the door. Beyond it, a courtyard under the dark sky. Damp, dirty, cold and loud. Large posters, neon signage, flashing screens.

Oh, the skyline! Hazy. I can barely see anything besides the lady who smiles too widely. Perfect teeth. Crows. Cables. AC units. Pipes. Too many to count. Garbage bins, yet trash surrounds them anyway.

Wait, are these...outlines? Objects suspended in cuboidal wireframes – are they digital overlays, or projections of a fractured psyche onto physical space?

The more I observe, the less I comprehend. Everything appears flawed. Glitched.

This space, this reality…is it absolute, or mine?

Am I out of my mind…or in it?

Musings on space, place, environments, cities and the myriad ways they are devised and occupied flooded my sentience when I first played Observer: System Redux (remake of the 2016-released Observer) in 2023. Having just switched to pursuing an alternative mode of practice in architecture, I was operating from a space of flux situated between architecture—built and unbuilt—and writing about it; my new identity quietly being shaped through the media I consumed and the digital worlds I explored. A few minutes into the playthrough of the video game, I had experienced hints of derealisation, entrapment and paranoia, fueled by its ‘fabricated’ conditions; intentioned, designed. I witnessed the role of architecture extending far beyond that of place, acting as a spatial extension of a hive-mind of experiences – lived and imagined. I continued to explore more video games after playing Observer: SR—from single-player story-mode games and open world role-playing games to multiplayer adventure-survival and first-person shooters (FPS)—which was bound to change how I saw, perceived and felt architecture.

Two years on, reading the UK-based publisher Routledge’s Architecture and Video Games: Intersecting Worlds, edited by Vincent Hui, Ryan Scavnicky and Tatiana Estrina, helped me articulate what I had only intuitively sensed through play, revealing how the two disciplines structurally, conceptually and pedagogically intertwined. Across essays and interviews from architects, designers, theorists and developers, it captures an iterative, evolving and transdisciplinary field: one that learns, adapts and evolves through the virtual medium of games and the immense word-building exercises they pose, often utilising coinciding systems—technology, spatial storytelling et al—that neither of the disciplines can fully contain on their own.

The book also makes visible a growing field of practitioners—including architects who practice with game engines; game designers who think like spatial storytellers and academics that employ hybrid pedagogical frameworks—fluidly moving between these fields, inviting readers to dwell on these examples and be inspired to create more hybrid spaces that draw from one another. The book lays out several opportunities to tangentially explore the underlying as well as explicit themes of worldbuilding methodologies for physical and virtual architecture, some of which are reflected on in this book review.

Harkening back to Observer, developed by Polish studio Bloober Team, the game’s premise takes the player to Kraków, Poland in 2084, unfolding within a tenement inspired by an actual location in the city’s old quarters. Players become Daniel Lazarski, the protagonist, played by Dutch actor Rutger Hauer (1944-2019). Best known for his role as the rebellious replicant Roy Batty in Blade Runner (1982)—a film widely known to spearhead the cyberpunk aesthetic and an inspiration behind the Polish game—Hauer now finds himself on the other side of the order, playing a neural police detective, an ‘observer’, equipped with cybernetics that help him hack minds. The game utilises architectural elements from the real world as anchors to contextualise players—a common occurrence in the industry, as Hui states in the chapter Architecture Manifesting Videogames Manifesting Architecture—creating a spatial framework that is reminiscent of Polish architecture, using apartment designs, furniture designs and other props as touchpoints.

The game developers, further, thoughtfully integrate socio-political tensions—referencing Poland's history of totalitarianism, specifically under the communist regime of the Polish People's Republic—into an abstract, retro-futuristic and atmospheric horror. Free from the ‘constraints’ of explicitly habitable, real-world architecture, the game speculates a future that feels both alien and strangely familiar, prompting reflection on social responsibility in the present. Along the same lines, an interview in the book with MIT Game Lab’s Program Manager Rik Eberhardt reveals that games often function best as ethical mirrors when the themes are more abstract and underlying. Games like Cities: Skylines (2015) and inZoi (2025) that prioritise accuracy in simulations and mimicking realism, on the other hand, do not allow any buffer or incite curiosity for players to confront uncomfortable questions of power, urban systems, digital technology and philosophy, which games like Observer and Disco Elysium (2019) and the intentioned distortion and hybridisation of their architecture do rather brilliantly.

The dystopian, cyberpunk world of the psychological horror game is a complex system, established and lent further definition by layers of discrepancies. The tenement’s physical space, for instance, doctored through digital layering and psychological distortion, becomes a volatile site of manipulated memory and emotion to propound a false sense of control in the video game. Everything that is twisted, interpreted, exaggerated and erased from the real, physical space is translated into distinct, bona-fide elements in the virtual world, definitive of not only the game's atmosphere, but its spaces and intended interactions, without being relegated to a backdrop.

In the chapter Game Worlds as Real Worlds, for instance, illustrators Sandra Youkhana and Luke Caspar Pearson recall social and cultural theorist Graeme Kirkpatrick’s commentary on these “discrepant” experiences, wherein one’s actions are guided by the visual, environmental and narrative coherence of the virtual world, as though navigating an architectural domain. Youkhana and Pearson argue that the complex relationship between environment design in games and user agency is what underpins the ontology of virtual worlds, whose diverging realities could be seen as “truthful settings” that affect a constrained environment. This suggests that spatial cues, ranging from simple, smaller interactions to broad, complex designs, have the capacity to evoke emotional responses and are essential in shaping immersive experiences—especially spatially driven—in games. Across both forms of media, worldbuilding thus transcends the simple act of making buildings; it entails imbuing conflicting, discrepant elements of shared memory and lived and speculated experiences to evoke emotional responses, creating a conditional environment that evolves with its users.

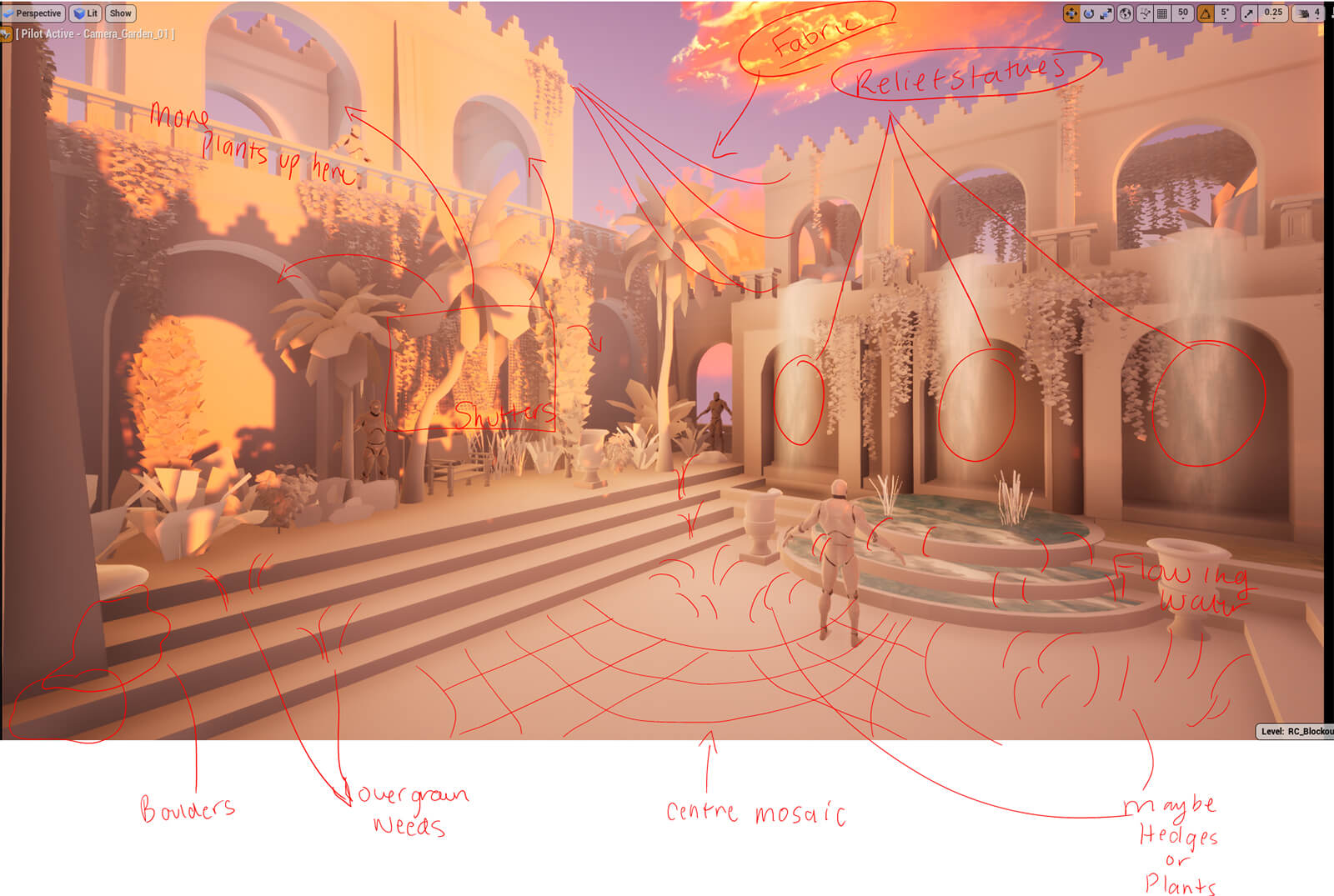

Unlike game design—where imperfections, irregularities, subjectivity and experimentation are often part of the process and the experience—discrepancies such as these are almost unthinkable in physical, built architecture, where different stakes inform decision-making. In the chapter Oh Shit I Took Both Pills, and Now Architecture is NO LONGER Frozen Music!!, architect and game designer Leah Wulfman critiques this rigid understanding of traditional architecture and methodologies, calling into question its continued reliance on blank physical models and 3D visualisations. The discursive structure of their mixed reality design-build prototyping studio at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor Taubman School of Architecture and Urban Planning, GAYMING ARCHITECTURES, thus involved exposing students to a variety of visual cultures such as graphic novels, manga and video games to imagine what they would term queer architecture.

Building upon Wulfman’s reframed architectural thinking, architectural designer and author Viola Ago further underlines the role of a creative author’s self—cultural, biological, anthropological and sensorial—in defining these pedagogical frameworks in the chapter The Digital Imaginary: The Confluence of Author and Product in Physics Simulation Engines. Ago suggests moving from a position of a distant observer between the author and the creation to a place that is “personal, unapologetically subjective and related to a lived experience” through situational models. In this light, architects may become iterative facilitators that guide the process of worldbuilding, with intuition, tools and even the users as collaborators.

Eberhardt further explores this idea of user agency in the book by underlining the role played by functions or objectives in both virtual and physical environments in gaming and architecture, respectively. For example, first person shooter games like Valorant (2020) present game environments as tactical zones, narrowing spatial awareness beyond the objective, while games like The Sims franchise allow more freedom and creativity to work within the boundaries of immediate goals (also granting the option to bypass them). These examples highlight how games may place user agency at their centre, highlighting how they govern spatial experience that may often be constrained by practicable design, laws and norms.

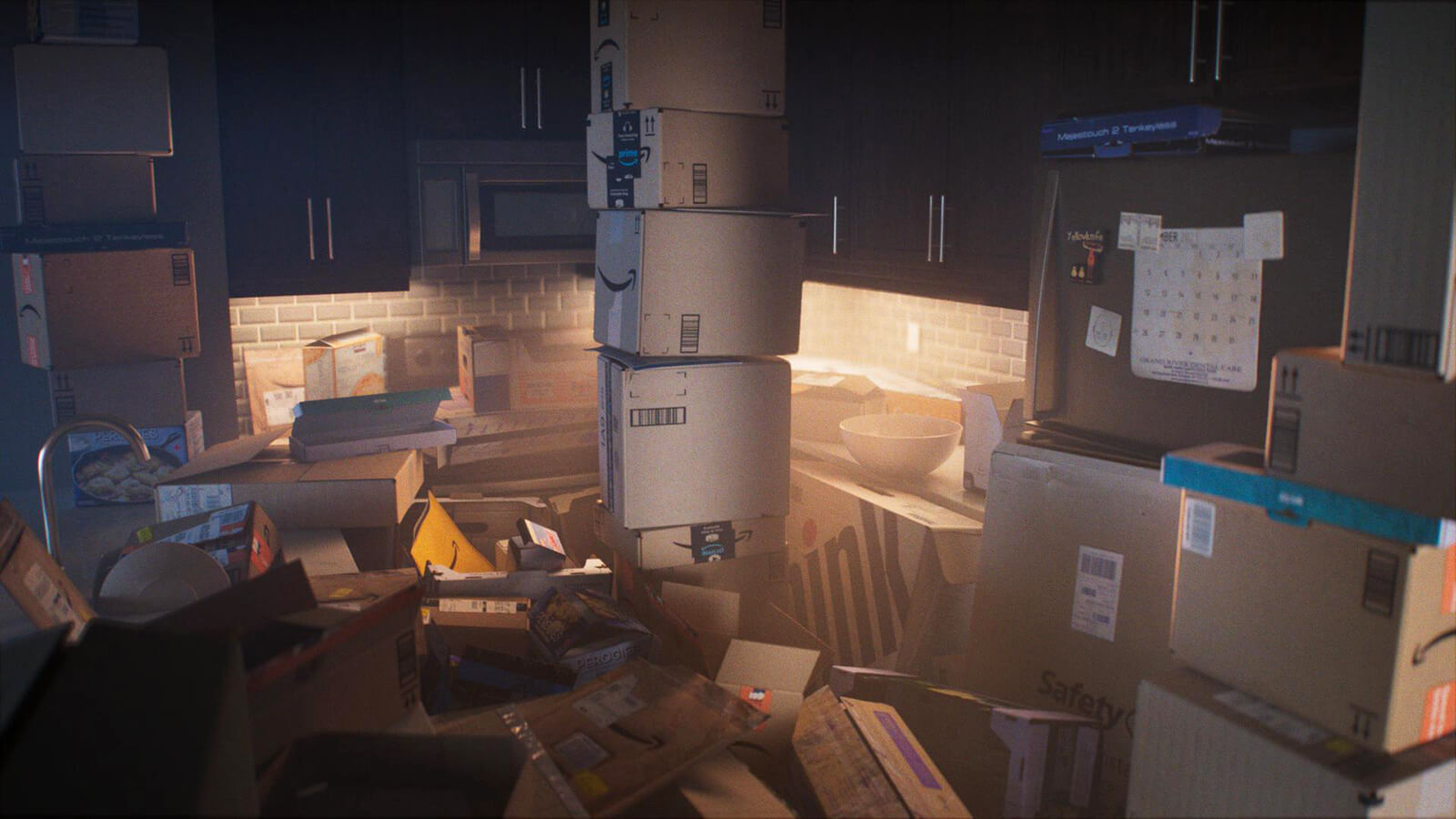

In contrast to the physical realm, virtual worlds can thus stand to invite far more exploration, experimentation and intuitive engagement. In both virtual and physical spaces, architecture is that interface facilitating user agency and spatial interaction. This becomes especially apparent in sandbox and simulation games, where players engage in iterative acts of design, curation and construction and perform everyday activities with much intent and deliberation. The Sims 4, a particularly successful example among life-simulation games, allows users to imagine alternative lifestyles and realities for their in-game characters through a rather joyful curation of architecture and design environments that may be seen as a quiet resistance against the rigid frameworks of the discipline and the toil of its slow realisation.

Featuring several architectural, furniture and decoration assets for players to choose, drag and position in spaces of their own design and choosing, The Sims 4 doubles up as a creative platform allowing players to familiarise themselves with acts of design and observe how their Sims interact with their built environments. However, since the game was created by an American architect, the game’s inbuilt assets often tend to resonate more with Western cultures and audiences. In the chapter Building Black Joy in a SIMulated Realm, designer and educator Kristen Mimms Scavnicky spotlights a crucial component of the gaming industry in this regard, i.e. modding, which allows users to claim authorship over immersive experiences with custom content (CC). To combat this underrepresentation in game design and the objects which mimic and populate the game’s virtual world, its community actively releases CCs to cater to users with different socio-cultural backgrounds and varied design preferences. Apart from CCs, I increasingly find myself using shader overlays, texture and lighting packs and reworked assets to customise my gaming experience and modify it precisely to my liking – a coalition of two distinct but intersectional mediums and planes of thought.

“The space of a videogame is the space of architectural thinking,” writes Ryan Scavnicky in the chapter Paper Visions: Theorizing Virtual Architecture. He argues that the space of a game extends beyond the virtual built environments, to the player's physical space or “containers” that they game from, along with the socio-cultural landscape they inhabit. My container—a cubical haven in the corner of my house—houses a small desk from which I play and work using modest gear. Just like Scavnicky, my Twitch livestreaming chat acts as another virtual site for introspection, where the viewers’ perceived understanding of my gaming experience adds layers to my own experience of the virtual world. This ‘multiplayer’ system in turn generates a cycle of infinite play and discourse on virtual and physical architecture, fusing authored and inhabited worlds, the observers and the observed. To that effect, game designer Damjan Jovanovic recalls words from academic James P. Carse’s book Finite and Infinite Games (1986) in the chapter Infinite Play: “a finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play”, alluding to the pervasiveness of the virtual worlds of the game beyond the screen.

While penning this review, I could not resist returning to Observer: SR. This time, I experienced the game not with the intent of leisurely exploration, but with the resolve of recognising thematic cues and identifying possibilities of spatial examination. “Remain in your apartments and enjoy your chosen holographic content”, the game’s voiceover echoes in my room and fills it, as I continue to dwell on curated escapism and a feeble sense of control we perceive our realities with.

A narrow hallway. A closed door at the end. Cables run across the floor and ceiling like arteries of a living, twitching system. On the walls? Signs, mirrors of popular culture. Rudy carefully vacuums the floor. War veteran Janus unlocks the door. Beyond it, a dark, familiar courtyard drowns in the noise of the city.

The skyline remains hazy, yet I do not squint my eyes to look farther. Creepy advertisements. Circling crows. Entangled cables. They have all become carriers of the noise, conditioned by the tensions of its world.

The irregular digital overlays are now placeholders of fragmented architecture.

The more I observe, the more I embrace the discrepancies.

The fractured realities, the intersecting worlds…they belong to all of us.

Am I finally in a space that can hold it both? Architecture and Video Games?

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Bansari Paghdar | Published on : Aug 07, 2025

What do you think?