Photographing the multivalence of 'Sacred Modernity' with Jamie McGregor Smith

by Jincy IypeMay 16, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Oct 17, 2024

"We believe a careful documentation and analysis of [Las Vegas’ Route 91, the archetype of the commercial strip] is as important to architects and urbanists today as were the studies of medieval Europe and ancient Rome and Greece to earlier generations. Such a study will help to define a new type of urban form emerging in America and Europe, radically different from that we have known; [which] we define today as urban sprawl." - Brief for the Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi-led studio at Yale School of Art and Architecture in 1968

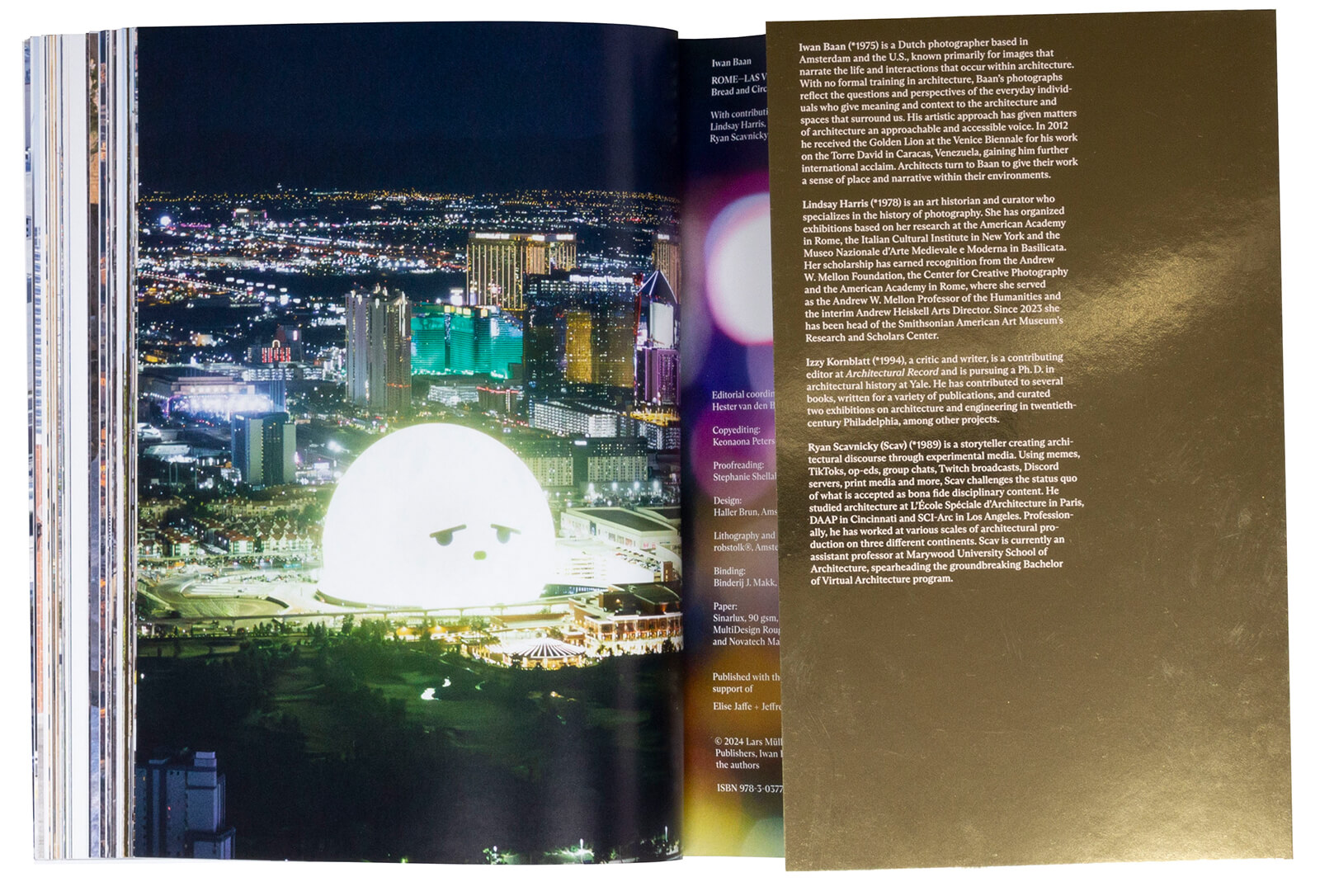

American architects Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi undertook an architecture studio at Yale in the summer of 1968, intending to document and record the ‘ugly and ordinary’ architecture of the Las Vegas strip for the emerging car-centric city. The research conducted in the studio would eventually be turned into Learning from Las Vegas (1972), co-authored with Steven Izenour, the polemical book that highlighted the lessons from the desert town, presenting Vegas as a symbol to critique modernist architecture. The book’s focus on the commercial architecture of the Strip was a proposal by the architects for architecture to embrace popular culture and everyday life as a way to communicate meaning; a rhetoric that still finds relevance today. The book—which heralded the grandiose era of postmodernism—and its concern with the ordinary undergirds architectural photographer Iwan Baan’s exploration of Rome and Las Vegas in a new book Rome – Las Vegas: Bread and Circuses.

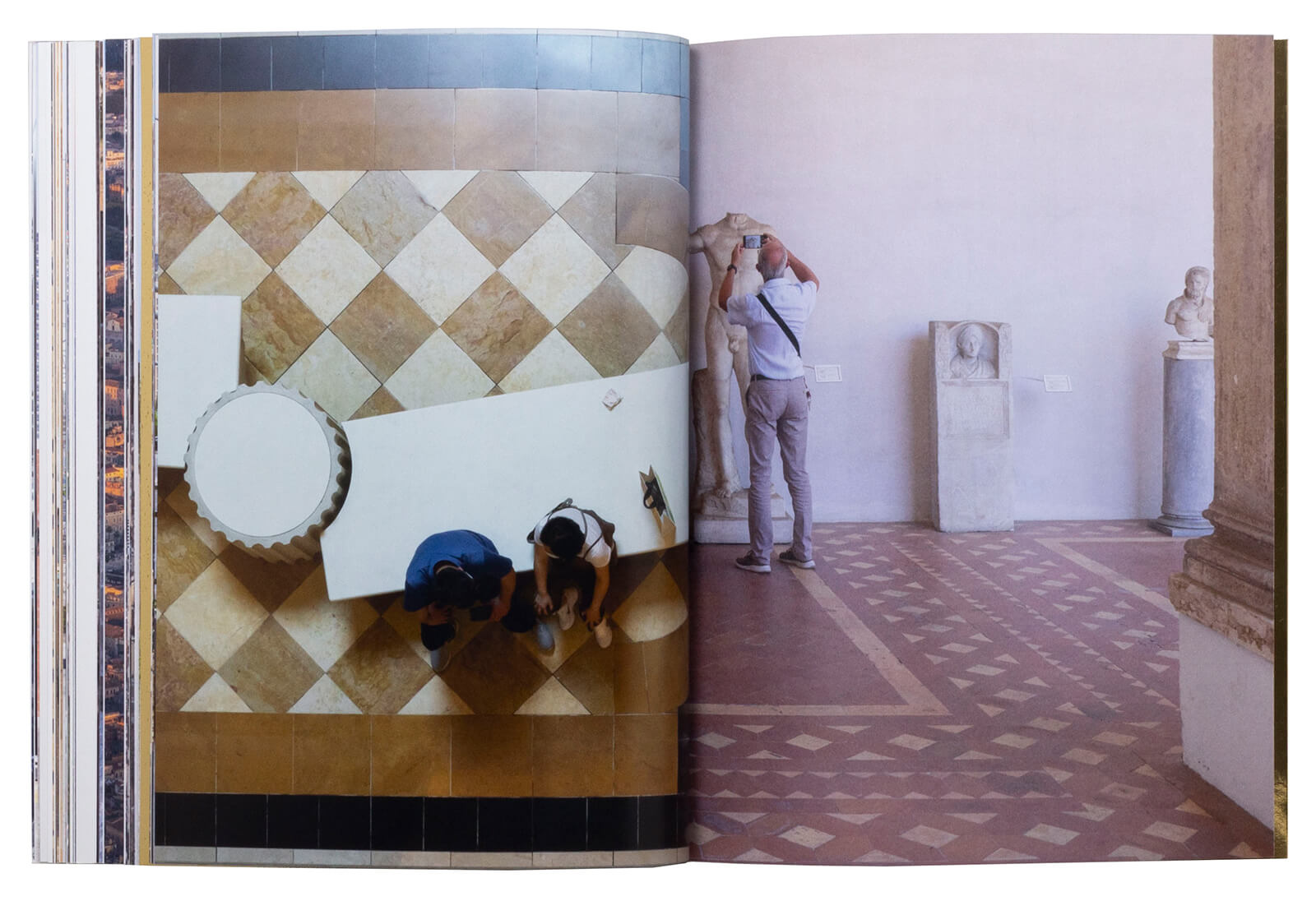

The photographs reproduced in the book were taken by Baan during a residency at the American Academy in Rome, where he examined the dialogue between the Italian capital and America’s playground. “In developing my book Rome – Las Vegas, I was interested in the perceived polarity of these two fabled cities and the juxtaposition of the ancient and the new, from the Colosseum to the Casino,” explains the Dutch photographer in an official release about the book. “In Las Vegas, what was once a flat strip decorated with neon signs is now much more elaborate, marked by high-rises and buildings all trying to be something else. Meanwhile, in Rome, there is something uncanny about ancient buildings plastered with billboards, or the cafeteria in the Vatican decorated with a poster mural of the Vatican, as if the simulated image brings you closer to the real thing.” The almost artificial quality of both cities as emphasised by Baan in his statement also becomes the focus for many of his images, lending these a certain perverseness; the removal from reality makes the reader/viewer question what the image of the city represents.

These architectural photographs were initially displayed in an exhibition at the academy in Italy in 2022. The showcase delved into “a transnational look at resonances in architecture, urbanism and the social uses of space between legendary cities in Italy and the United States,” elaborates Lindsay Harris who curated the exhibition. By linking the American city to the cradle of Western civilisation (and some could argue its architecture), it also spotlights how Italy vitally informed Venturi’s thinking, evident in the book he wrote in 1966. In Baan’s astounding compositions—whether aerial views or street photographs—it is revealed that the cities share more similarities in the complexities and contradictions of their built fabric than is evident to the naked eye.

To Scott Brown and Venturi, Rome and Las Vegas already held several parallels leading them to consider the lowbrow urbanism of Vegas as the apotheosis of a new kind of urban form. Each was set within a sparse context; the expansive landscapes of the Campagna and the Mojave Desert respectively lending focus to the urban spaces of each. Further, the duo believed that what attracted designers and urban planners to Rome and its piazzas was mirrored in Las Vegas and its Strip, albeit in a different context. “Las Vegas is to the Strip what Rome is to the Piazza,” they wrote. And perhaps most significant to Baan’s book, each city fosters its own versions of monumentality: Rome’s churches and Vegas’ casinos; each a public space in its own right.

The volume is bookended by two sets of diptychs contrasting one city to the other: where the monumentality of St Peter’s Basilica is comparable in some sense to the Excalibur hotel and casino; where the surroundings of Roman plazas seem hardly to have changed, but Vegas is now dominated by skyscrapers; or the spectacle of the Sistine Chapel frescoes reads the same as the grandeur and chaos of Caesar’s Palace to a touristic experience. It is these comparisons, toeing the line between authenticity and artifice, between the monumental and the ordinary that bring to the fore the ultimate message of the photograph book, apart from a fascinating revisit of Las Vegas’ call to consider the seemingly banal. Throughout the volume, Baan draws our attention not only to the signs and symbols of these cities embodied in their architecture, from the Renaissance to the contemporary pastiche, but also how these symbols affect public perceptions of a place.

An essay by Ryan Scavnicky in the book points out how what we believe we know about both cities in question is really a construct fostered by the mediated realities we live in. Vegas today is more extravagant than ever, boasting not only entertainment through gambling, but food and shopping destinations; a holiday for the family! On the other hand, Rome is hardly a monument to the lost glory of Western civilisation, resembling more and more the kitsch version of the city recreated in Vegas. There are moments where Baan’s images of the two are almost too difficult to discern. In the essay, Scavnicky points to how global tourism skews our experiences of the city, writing, “The city actively creates a backdrop of excitement and wonder for visitors while hiding labour networks out of plain sight...Once those masks are jettisoned, we find each city’s brutal machinations hiding in plain sight. This apparatus is the result of a renewed era of global tourism...turning the new global city into a site of performance, thus revealing how public space and architecture are compelled to serve a new undeniable civic role: as a backdrop to be experienced and shared.”

If Rome once presented itself as an Enlightened city, it is now marked by this image of it; with tourist shops, performers and facade screens selling you an incomplete image; one particular photo with a billboard for fashion brand Valentino that declares “Roma is the place everything starts,” depicts this succinctly. Meanwhile, Vegas, with its grand canals in the Venetian and sham ruins (complete with charging outlets!) becomes more spectacle than material; doing its best to do away with sordid reality. In documenting Las Vegas, the authors of the 1972 book confronted the monuments of the city in a deadpan manner, photographing various buildings and spaces including Caesar’s Palace to remind readers that symbolism and ornament were central to architectural expression until the modernist era. That in removing ornament and iconography modernist architects had taken to building ducks or buildings as symbols. Today, it is perhaps just this that Vegas tends to. What distinction do the monuments of the city hold for the tourist, image-obsessed cities today?

In present-day context the call to look at the ordinary and Scott Brown and Venturi’s central question, “Is the sign the building or is the building the sign?” takes on an entirely different meaning. The overall system of communication and form they hoped to study seems to only have become even more frenetic in our hypermediated age. The question, especially pertinent when studying Baan’s images ought to be: How does the building add to your experience of the real? In what ways does it hold your attention?

Perhaps the most crucial example of this is Vegas’ latest attraction: the Sphere; both duck and decorated shed. In depicting the contexts each city is set within, Baan thus draws our attention not only to the symbolism but how this has evolved. It is this very context, in the aerial views that initiate each city’s sequence of images that reminds viewers that these cities are more than their symbols, that sprawl, overpopulation and migration have marked both cities, transforming them; presenting the duality of reality today: of the city for tourists and the lived city. If Scott Brown and Venturi declared in 1972, “Symbol dominates space. Architecture is not enough. Because the spatial relationships are made by symbols more than by forms, architecture in this landscape becomes a symbol in space rather than form in space.” The city produced and then reproduced in the images of the book is after all, there to be consumed “all for your delight.”

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Oct 17, 2024

What do you think?