'Tender Digitality' as a concept for humane and empathetic digital spaces

by Almas SadiqueMay 10, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Apr 30, 2025

The cover for architect and artist Anna Kostreva's recent book immediately draws one in, especially if you appreciate a meticulously detailed architectural drawing. Against an electric blue background, the minimal white lines of a tower are presented, in a side sectional view. Few books would go so far as to include such a clean section (it even details the foundation of the tower!) as its cover image, but then, Seeing Fire | Seeing Meadows is not an ordinary fictional book. It doesn't really fit an exact category. On Plural Studio's (the publisher) website, it is described as "a novel that foregrounds architecture into storytelling". When the protagonist, Natalie, is, in fact, an architect, this much feels like a given (architects are notorious for making work their life after all).

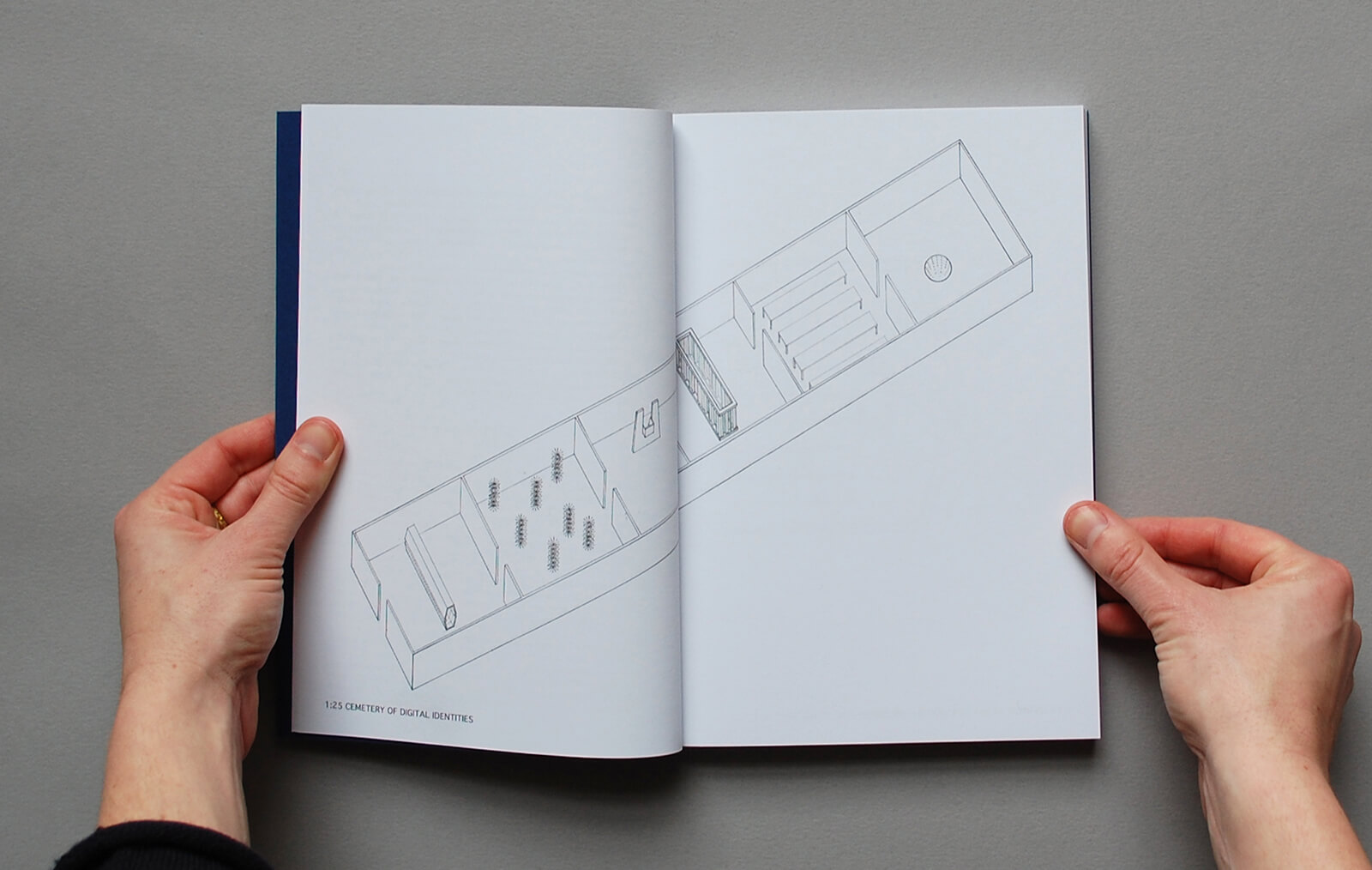

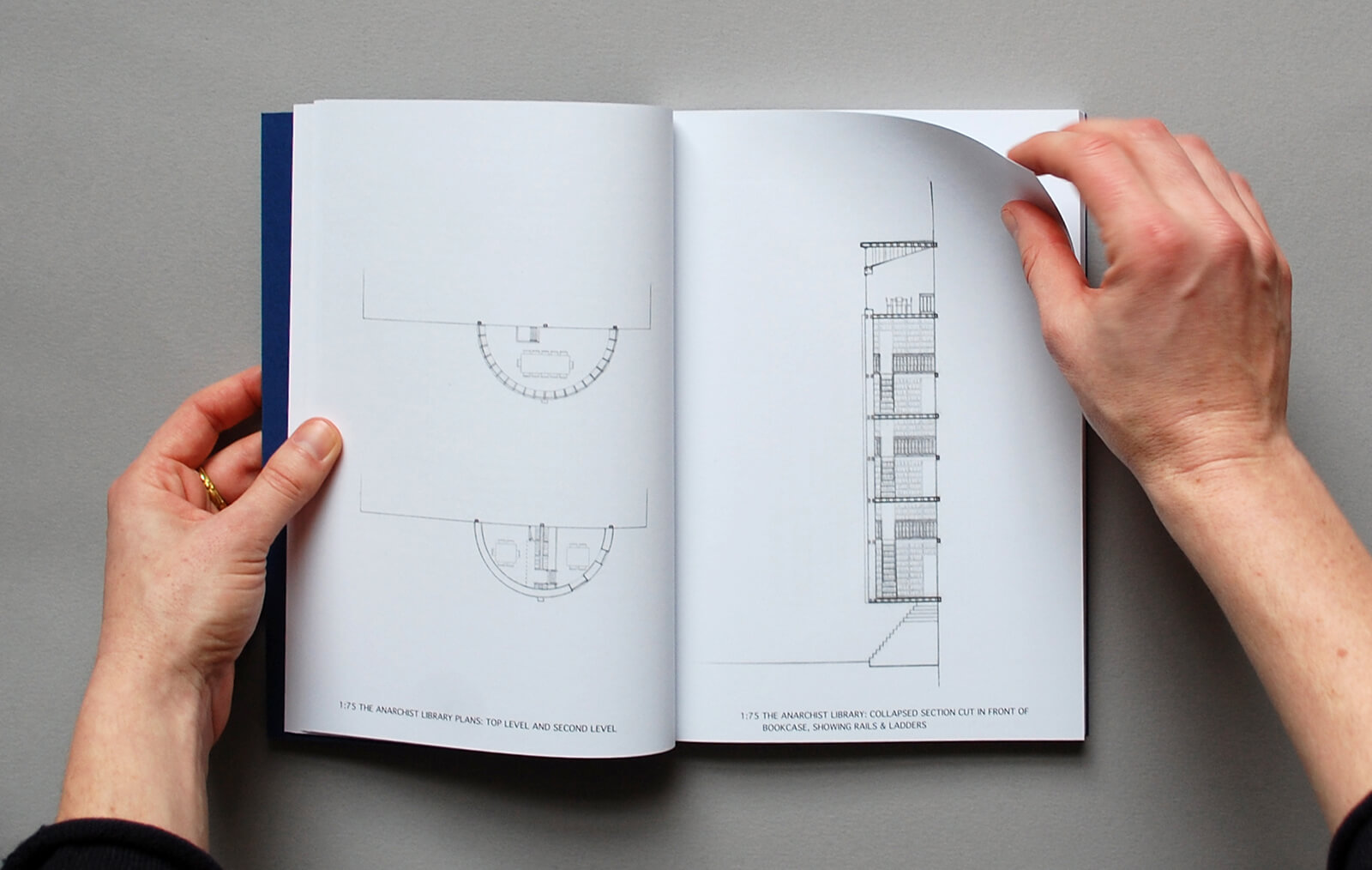

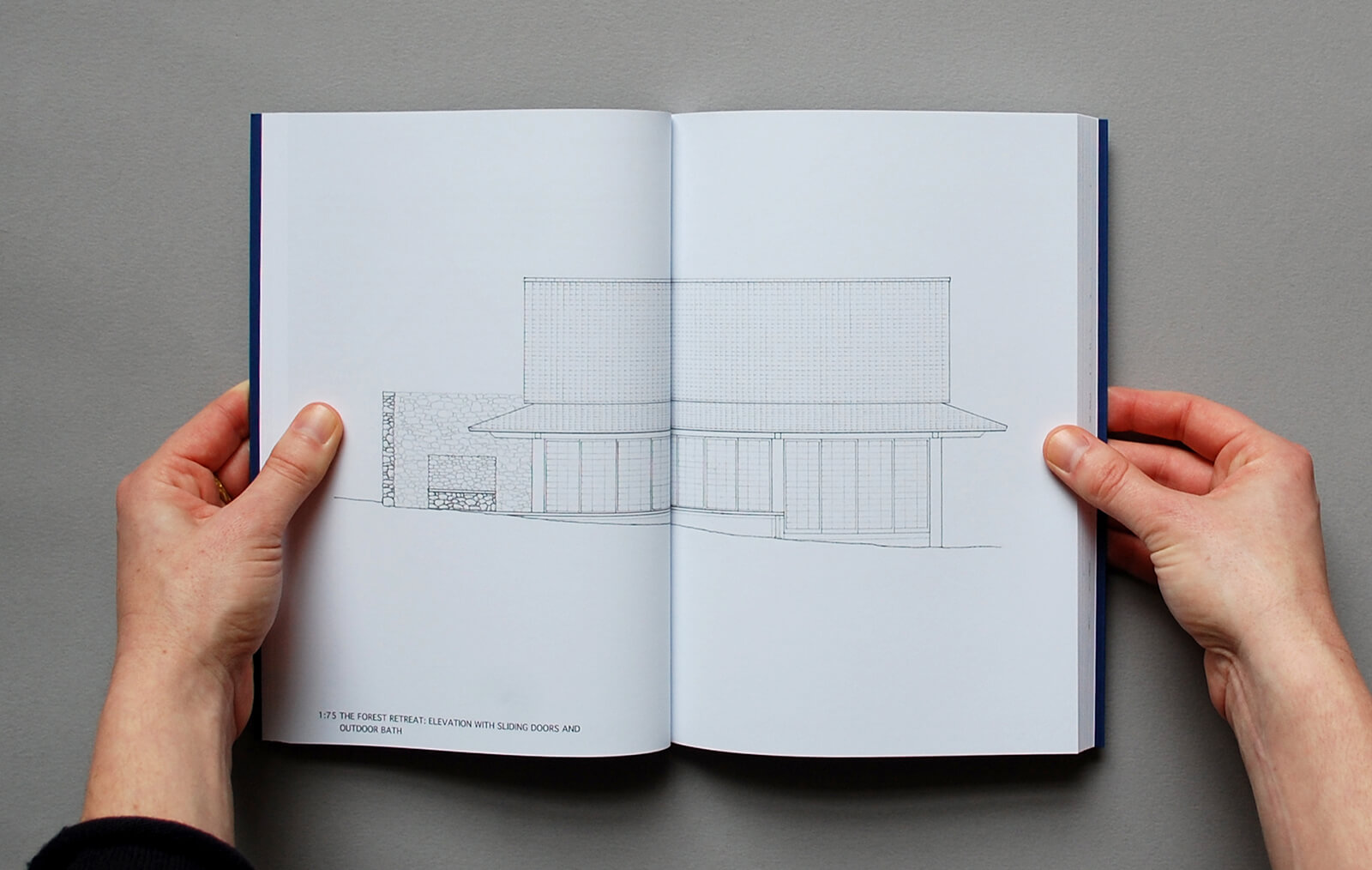

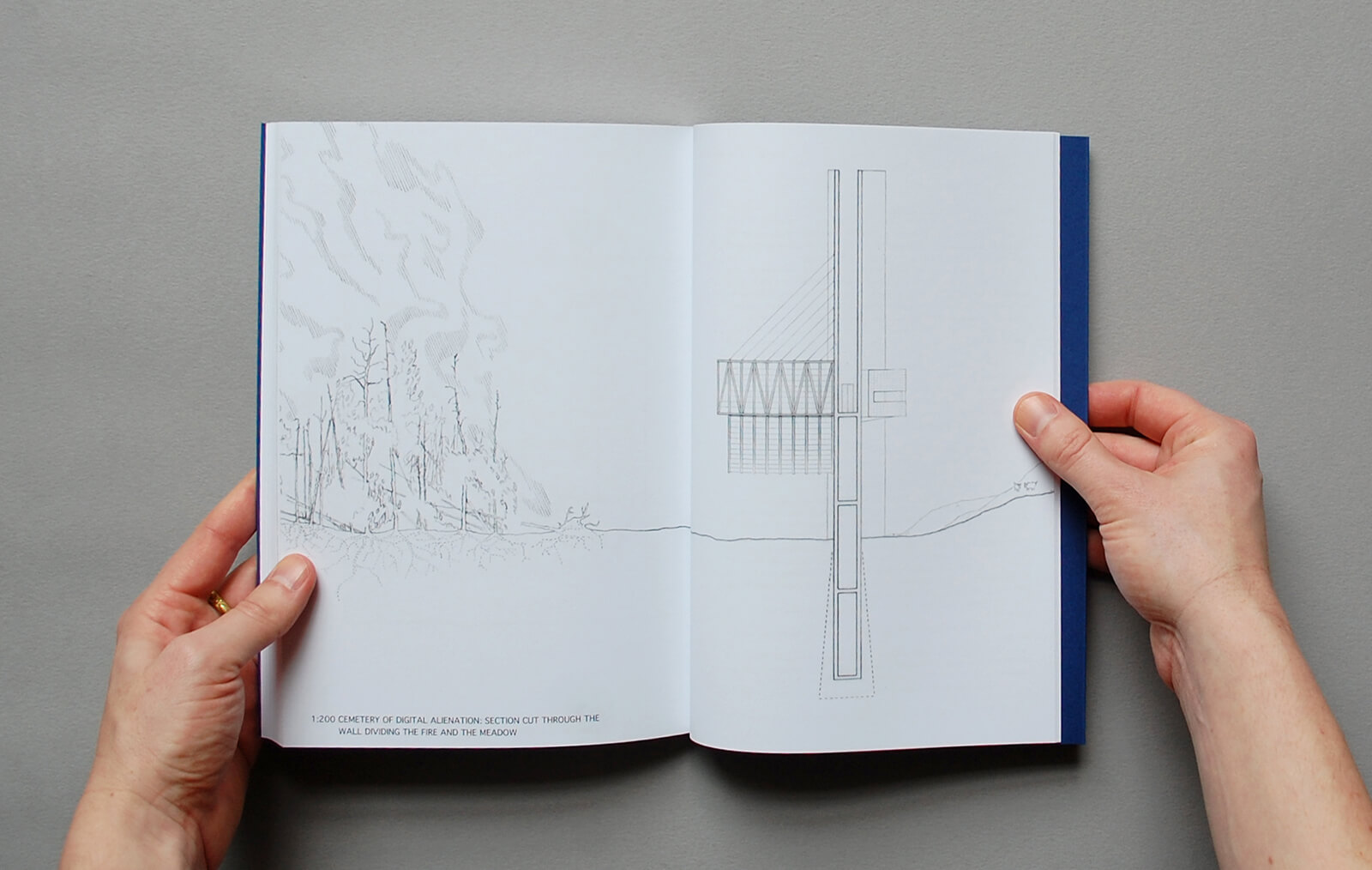

We are even introduced to Natalie's character through the plot device of drawings. The book's narrative begins in a bar where she is showcasing a selection of her 'speculative environments'—drawings that she painstakingly drafts after office hours—enjoying drafting as a means of thinking. Here, right off the bat, Kostreva clues discerning readers into one of the central themes of the book. The story, as Natalie’s preference for the manual medium of drafting seems to suggest, deals with the tension between our analogue realities and the perversions of the digital age. Through a fictitious narrative, Kostreva emphasises the anxieties engendered by a world increasingly defined by its intangibility, where everything we do seems to be dictated by algorithms. Drawings by Kostreva supplement the otherwise fast-paced story.

The science fiction plot depicts an alternate Berlin that is “governed by algorithms where human participation is rewarded with creature comforts as well as ecstatic experiences”. Kostreva’s story offers the logical conclusion to the age of the internet, where individual agencies are contested by the dominance of technological manipulation, a society made spectacle (to paraphrase Guy Debord). Early on, Kostreva (through her stand-in Natalie) betrays the source of what I understand inspired the book, Shoshana Zuboff's foundational text on 'big data', The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2018). The book's ethics hinge on the arguments Zuboff makes about our seemingly unconscious deference to and complicity in surveilling ourselves, by letting the data about our habits and preferences generated through online activity, manipulate us.

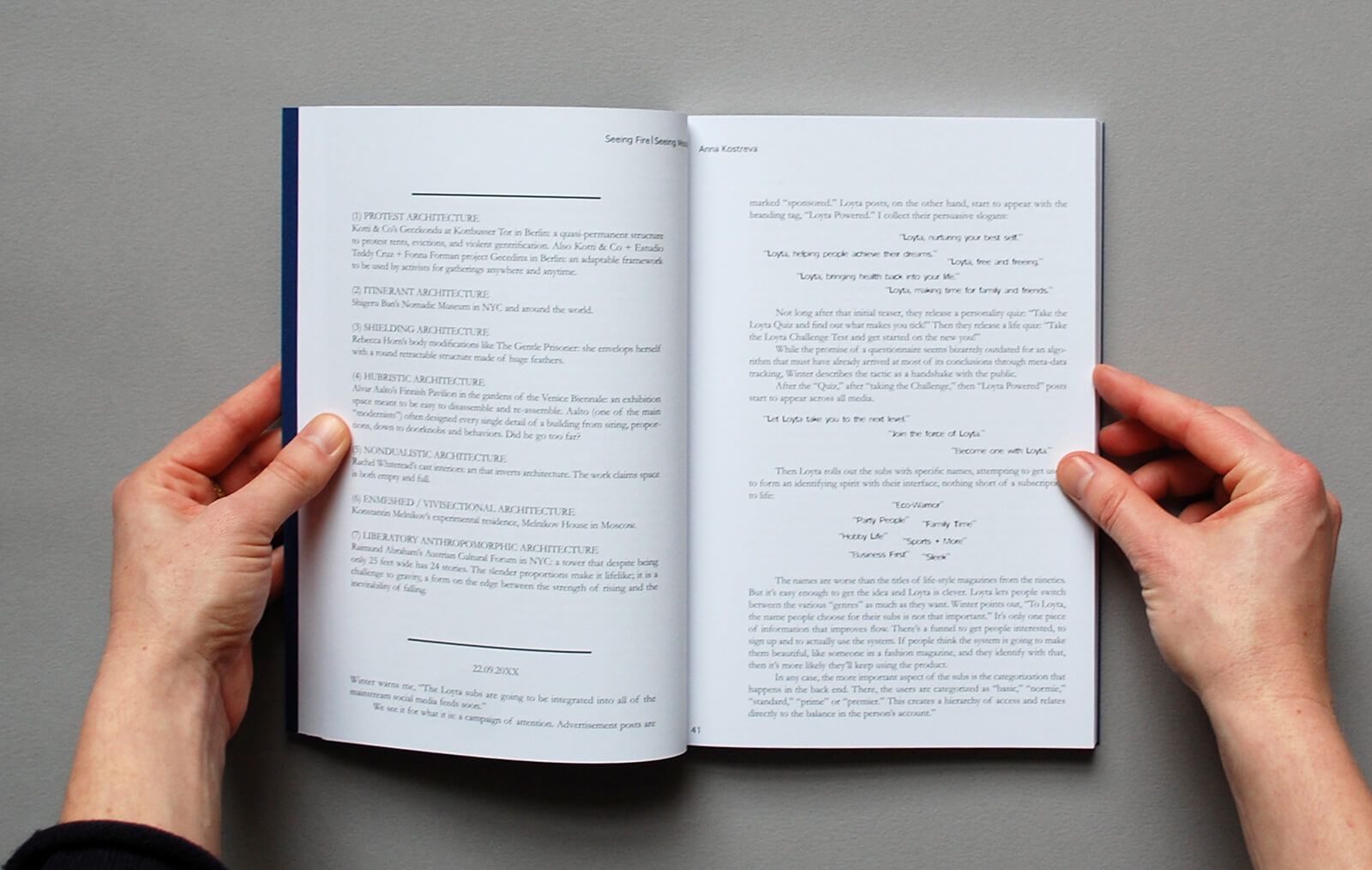

In the fictional world of Seeing Fire | Seeing Meadows, this control is exercised by a digital tech company called Loyta and their programme dubbed simply, the ‘subs’. The end goal for the company is to manufacture a world where there is no discernible difference between our digital personas and physical selves. This is provided as exposition from the other protagonist, Winter, who is a programmer with Loyta. Over a few months in the fictional city in Germany, the nascently launched programme asserts dominance, determining not only where people eat or what they wear, but even what they do, promising to turn them into their ‘best selves’. Ultimately, what Kostreva calls ‘subs’ amplify existing social disparities, with the algorithms limiting access to certain resources within certain ‘subs levels’ (or the people with means and those without). "The algorithms systemise social hierarchy and disadvantage," Kostreva notes. In this way, the subs also magnify the feelings of alienation from our communities. This book is beginning to sound disturbingly familiar.

In time, "the subs [become] a force in the city. It's no longer just culture and politics that shape the creation of the urban social space". The idea that the ‘subs’ determine the production of urban space brings to my mind French sociologist Henri Lefebvre’s theory on the social production of spaces, and how they reflect social hierarchies and practices. Here, by foregrounding the rapid progression of technology in our lives, Lefebvre’s notion is problematised. Technology not only affects the representation of space (creating a series of homogenised places), but stringently determines who is granted access, and what that access means based solely on our status, rendered ever more visible in today’s age than before. This further calls into question our experience of physical as well as digital space.

Today, the degree to which our digital lives take precedence over actual lived experience is quite obvious. Places are ‘instagrammable’, experiences are meant to be documented, and even activism is performative. Even the idea of a solely digital city (like the Metaverse) ceases to generate the same shock it might have 15 years ago. No other example illustrates the fatigue around digital anxieties better than the reception to the latest season of Black Mirror. The series began with twisted tales about the ways in which our devices manipulate our actions, and in recent episodes, even the melding of technology with humans did not generate the fanfare of earlier episodes. The plot points, on which the show dwells, however, are still worth mentioning. They show how the digital has very much taken over our lives, so much so that all humans are cyborgs in some sense, forever attached to their electronic devices.

In Seeing Fire | Seeing Meadows, the only group to resist this blatant conversion of humans into commodity (or data meant to be harvested as a form of surveillance) is a group of ascetics who still believe in the power of community. On the other hand, while Natalie is fascinated by their cause, her conversations with Winter highlight her criticisms of the world. In an increasingly anxious dialogue, Natalie reiterates radical positions against oppression and control through a slew of architectural references. These range from Shigeru Ban’s ephemeral architecture to Konstantin Melnikov’s experimental residence to the now-infamous Nakagin Capsule Tower, designed by Kisho Kurokawa. Each provides a different reimagining of the conventional understandings of architecture, thinking of alternatives to construction waste and the agency of the individual within built environments.

It is this imagining of alternative ways of being that do away with the detached digital realm (as envisioned by the revolutionary group through a 'Faraday bus', a device that would shield users from the panoptic eye of the subs) and foregrounds our agency, revealing the story’s true heart. As a counter to the increasing dissolution of our lives into the digital, Kostreva posits “the poetics of a material proposition”. In this vein, we could also understand the drawings interspersed throughout the book, which remind us of a tangible reality, depicting buildings in meticulous, almost painstaking detail.

As most reviews have observed, the names of some of these drawings, such as the Cemetery of Digital Identities, The Identity Ring, Cemetery of the Digital Individual or the Cemetery of Digital Alienation, call to mind John Hejduk and his notion of the ‘architecture of pessimism’. Through speculative drawings, Hejduk hoped to centre tactility and sensuality in architecture, as opposed to what he claimed was ‘the architecture of optimism’ (or high modernism). By referencing Hejduk, and also Lebbeus Woods (directly named in the story by Natalie), Kostreva’s drawings—some of physical locations in the story and some purely fictional architecture—critique the fragmentation we experience in digital spaces. By depicting what is inherently abstract in visible form, Kostreva asks readers to imagine a world that can divest from digitality.

Ultimately, Kostreva’s book is a plea to think about how we interact with technology and, further, to find and invest in community. There’s a satisfying circularity to it, beginning with the representation of a cemetery of digital identities and ending with the loss of alienation. In this sense, the book also brings to mind Michel de Certeau’s Situationist philosophies. The story’s pace and narrative seem to match de Certeau’s idea of walking in the city as a form of asserting agency against an otherwise homogenising force (the city’s map). Similarly, Natalie’s interactions with others, her preference for drawing by hand and her insistence on going against the ‘subs’ is a way to assert herself. Individuality versus community, the machine versus the hand: these have been concerns for architecture since the discipline was defined. They’re only magnified by technology, as demonstrated by the book.

And while Seeing Fire | Seeing Meadows is dystopian in its premise, it ends up feeling not nearly as far-fetched as anything else occurring in today's world—not the onslaught of AI, not mass genocide, not even the slow death of our ecosystems (all of which are ultimately rendered with the same level of triviality on social media). It does, however, leave me with far more questions than answers about the world we live in, perhaps the mark of a good novel. As communities continue to be fragmented and alienated from each other and material conditions, what are the ways to imagine otherwise? Does digital democracy still exist? Are there ways we can build community in the age of social media? Should architects attempt to engineer free will? How is the control exercised by technology exacerbated with the advent of artificial intelligence? At the precipice of ‘fire’ and ‘meadows’, how will we choose to act?

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Apr 30, 2025

What do you think?