The home and the world: Rashid Johnson’s multivalent Black selfhood

by Avani Tandon VieiraJun 24, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Manu SharmaPublished on : Mar 14, 2025

The New Television: Video After Television is a hardcover book published by no place press on December 31, 2024. The book design features a facsimile of the older publication The New Television: A Public/Private Art (1977), a compilation of conference proceedings from the Open Circuits conference, which focused on important television and video art, held at MoMA, New York, in January 1974. Additionally, The New Television presents new essays by authors including Kris Paulsen, associate professor of History of Art at Ohio State University, Tina Rivers Ryan, editor in chief of Artforum, Helena Shaskevich, adjunct professor of Art History, Music and Art at Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) and several others, examining the contemporary state of video art and mass media. The New Television is edited by Rachel Churner, director of Carolee Schneemann Foundation, Rebecca Cleman, executive director of Electronic Arts Intermix and Tyler Maxin, curator at Blank Forms.

As collage technique replaced oil paint, the cathode ray tube will replace the canvas. – Nam June Paik, artist

The New Television begins with the older text A Public/Private Art, opening up with an introduction by Allison Simmons, who was an assistant to Howard Wise (1903 – 1989), a gallerist and notable patron of early electronic art. Simmons contextualises the relationship between televisual technology and art, starting with a statement on one of the earliest televisual broadcasting experiments conducted by the Radio Corporation of America in the late 1920s. It featured a papier-mâché statue of the comic character Felix the Cat, placed on a turntable in New York, with his photoelectrically converted image broadcast to a few thousand video enthusiasts in Kansas. Simmons adds, “Less than fifty years later, we were receiving similar rough, slatted television images from the moon…Even in a society whose economics necessarily align innovation with progress, it is hard to overestimate the significance of this extraordinary leap.”

Simmons tells us, “There are no credible factual accounts of the earliest steps taken by artists to work in television, either by telecasting film works made with an eye for home TV reception, or by actively producing works within the context of television itself.” However, she does highlight some early artworks featuring television sets created across the western hemisphere. Notably, she brings to our attention German artist Wolf Vostell’s (1932 – 1998) video artwork Ereignisse für Millionen (around 1963), which may be the very first example of glitch art if we are to read ‘glitch’ as a purposeful obfuscation of digital visual data. Vostell created a three-minute-long TV programme that was deliberately blurred by the broadcasting station, presumably resulting in viewers fumbling with their television sets for the broadcast's length before realising that their units were not defective.

Naturally, the author spends a significant portion of this section discussing pioneering South Korean artist Nam June Paik. Among other works, Simmons mentions the video art piece that Paik is most famous for—his 1965 recording of Pope John Paul I’s visit to New York in the United States using the unwieldy Sony TCV-2010, a combined video camera that included the world’s first consumer video recorder, the CV-2000. At the time, Paik pointedly predicted that “as collage technique replaced oil paint, the cathode ray tube will replace the canvas”.

The New Television wraps up its primer with a brief history of videotapes in Western art institutions. Simmons tells us that in the early 1970s, German art museums were beginning to collect and exhibit video recordings, which was concurrent with the 1972 edition of Documenta, where German video artist Gerry Schum (1938 – 1973) organised a video art section in collaboration with legendary Swiss curator and artist Harald Szeemann (1933 – 2005). Meanwhile, the Everson Museum in New York saw the first full-time department of video arts established, running a programme of solo shows of artists such as Paik, Chilean artist Juan Downey (1940 –1993) and American artist Bill Viola (1951 – 2024).

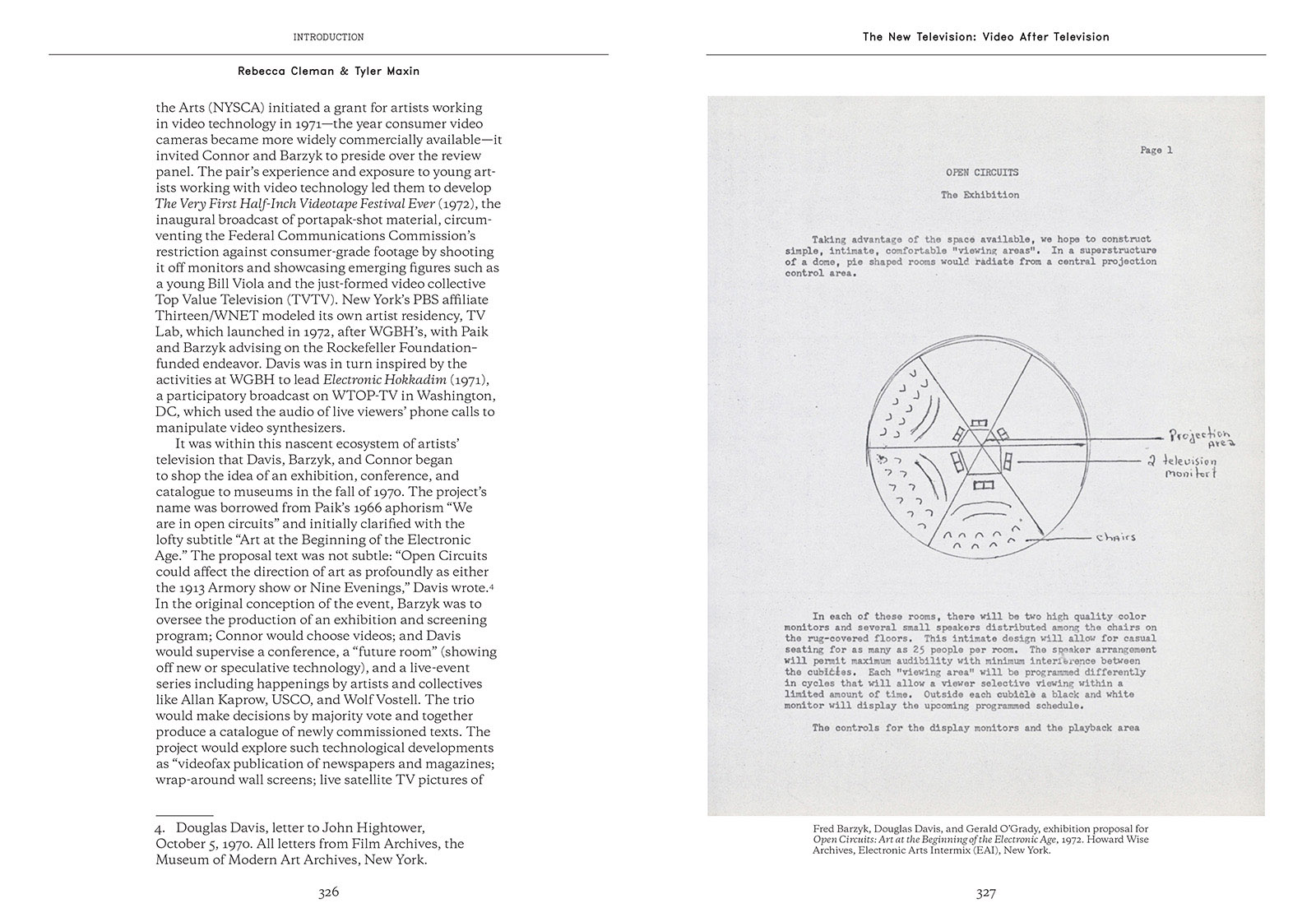

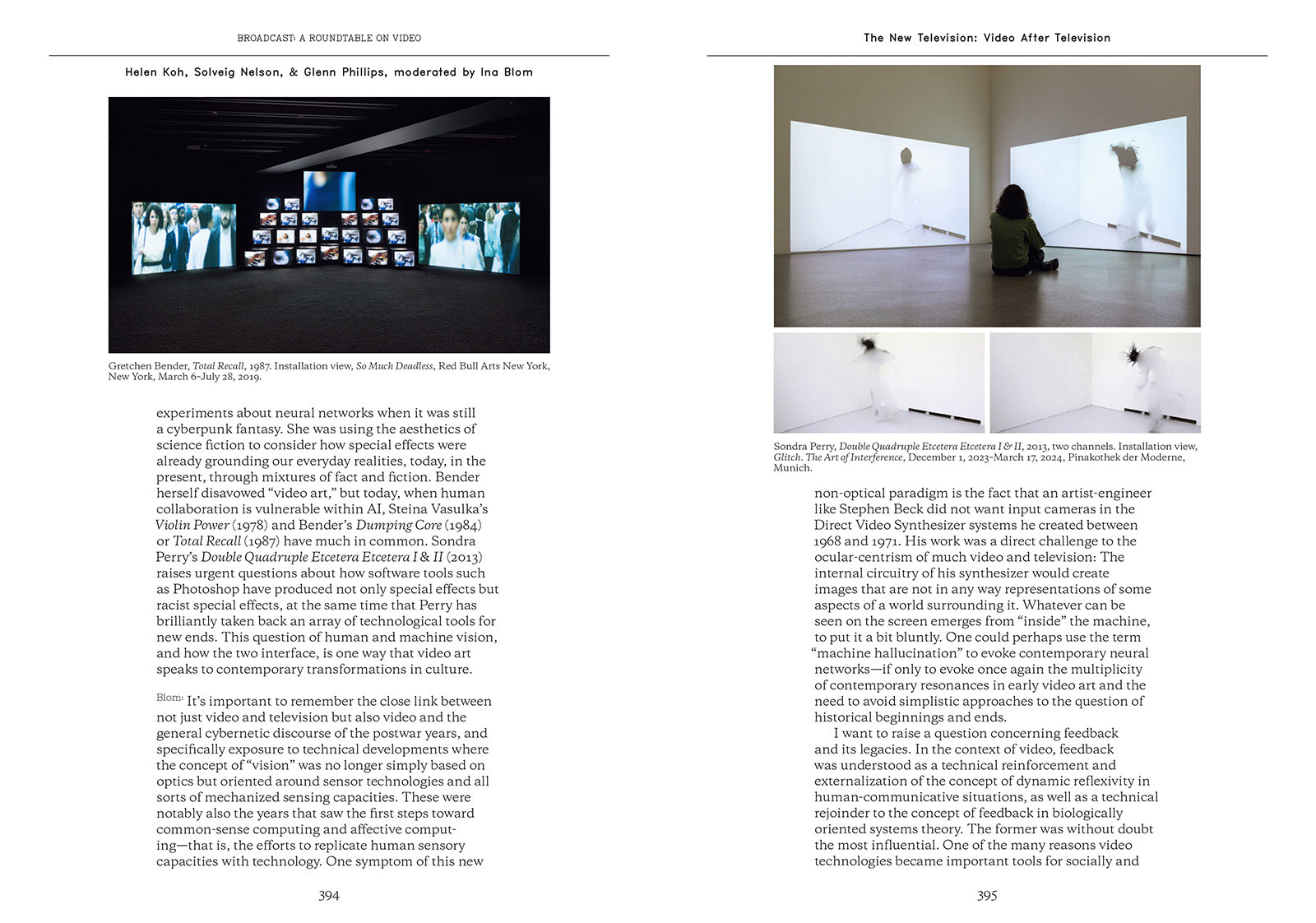

Simmons ends A Public/Private Art’s introduction by introducing the Open Circuits conference, featuring presentations and discussions by around 40 video artists, filmmakers, curators and critics. It was organised by American artist and writer Douglas Davis (1933 – 2014) and John Hightower (1933 – 2013), the director of MoMA at the time. Prior to the publication of Video After Television, the conference had largely fallen out of memory, as A Public/Private Art had long since gone out of print. With the publication of this book, we can see a glimpse of art history in the making: a utopian vision put forth by the participants through three distinct approaches to video art. The first sought to reshape broadcast structures, introducing digital art into mainstream media channels. The aforementioned Ereignisse für Millionen can be considered an example of this. The second approach attempted to create novel visual art by manipulating television signals through video synthesisers and computers. The American artist Stephen Beck, present at the conference, began creating the Beck Direct Video Synthesizer series in 1968 to facilitate this form of video art production. Finally, the approach focusing conceptual art treated the videotape as the object-medium. Much of Paik’s work sits here.

Revisiting Paik’s statement, one may read a sense of triumph at the video’s supposed destiny to upstage traditional art mediums. However, American art curator Jane Livingston took a different stance at the conference, choosing to reconcile video and traditional mediums instead. She brought American art critic Leo Steinberg’s (1920 – 2011) ‘Flatbed Principle’ to the table. Steinberg introduced the concept in a lecture at the Museum of Modern Art in 1968, asserting that, until recently, audiences had engaged with paintings as though they were windows into other spaces. However, when American artist Robert Rauschenberg (1925 – 2008) mounted his bed on the wall for Bed (1955), the canvas transformed into a bulletin board-like surface where objects could be placed and removed. We now had an art surface that did not function as a window into another space. Livingston sees this concept translated into the video medium. She added, “The idea of the video screen as a window is, ironically enough, I think, opposite from the truth in the use of video by the best people. Video in the hands of Bruce Nauman, or in the hands of Richard Serra, is opaque, as opposed to transparent. It’s an extension of a conceptual idea in art. It enables the audience, again on a very subliminal and intuitive level, to return to painting, to look at painting again, in a renewed way.”

The new essays in Video After Television approach video art and digital mass media from a variety of perspectives. The final piece, From Open Circuits to Surveillance Capitalism by Fred Turner, Harry and Norman Chandler Professor of Communication at Stanford University, strikes a sharp contrast with the prevalent optimism of the Open Circuits conference by reviewing its utopian objectives in light of where we are today. As Turner tells us, “[To the conference-goers], progress meant embracing the personal, the possibility of replacing one-to-many broadcasting with millions of one-to-one conversations. And that was where video came in. Broadcast TV required centralised studios, big budgets and big staffs. From giant towers, a network could beam the same signal to millions of homes simultaneously. Video could be made with handheld cameras and played back on the spot…Video was a ‘personal’ technology in the sense that laptop computers would soon be as well: It was small, portable and available to individual makers and local audiences.”

The attendees at Open Circuits believed that video technology would empower citizens to express their positions to one another personally, which would subvert the grand narratives that invariably proliferated authoritarian ideologies. In hindsight, they were only partially correct. While this facet of video technology evolved into digital communication and social media, it has led to a greater ideological fragmentation across societies than ever before. The author bemoans the contemporary media landscape, writing, “The decentralised, personalised media ecosystem is flourishing. But so too are global corporations, political extremism, propaganda and authoritarianism. Corporations and states are devoted to surveilling what we do and turning it into money or political power.” The book ends with Turner pointing to a silver lining: the personal is political now, like never before. Individual expression carries strong political messaging and social media has enabled us to spread those messages far and wide. We live in precarious times, with social and political shifts taking place at blinding speeds. However, it is certain that video technology and its extensions remain powerful catalysts, for better and for worse.

‘The New Television: Video After Television’ was published by no place press on December 31, 2024.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Manu Sharma | Published on : Mar 14, 2025

What do you think?