Discussion, discourse, and creative insight through STIRring conversations in 2022

by Jincy IypeDec 27, 2022

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Jincy IypePublished on : May 02, 2024

Produced and published by The Architectural Review and edited by Manon Mollard with John Jennifer Marx, Towards Abundance: the Delightful Paradoxes of Gender prompts us to perceive, exist, create and express beyond the rigid defaults of the gender binary in architecture. The liberating intent is outlined in the book's introduction thus so: “In this advocacy monograph, we hope to explore the paradoxical relationship between gender and architecture; to advocate for changes in how we see gender and as a result in how we design. While much work has been done, and still must be done, to bring parity and equality to the architectural profession, we wanted to go past discussions of labour statistics, to explore what is still being left out in the pursuit of progress.”

As I relished this succinct collection of essays by 16 contributors including Adam Nathaniel Furman, Ruth Lang, Yasmeen Lari and Marx themselves, I actively underlined passages on lived experiences, conformity and resistance against hetero-masculine privileges.

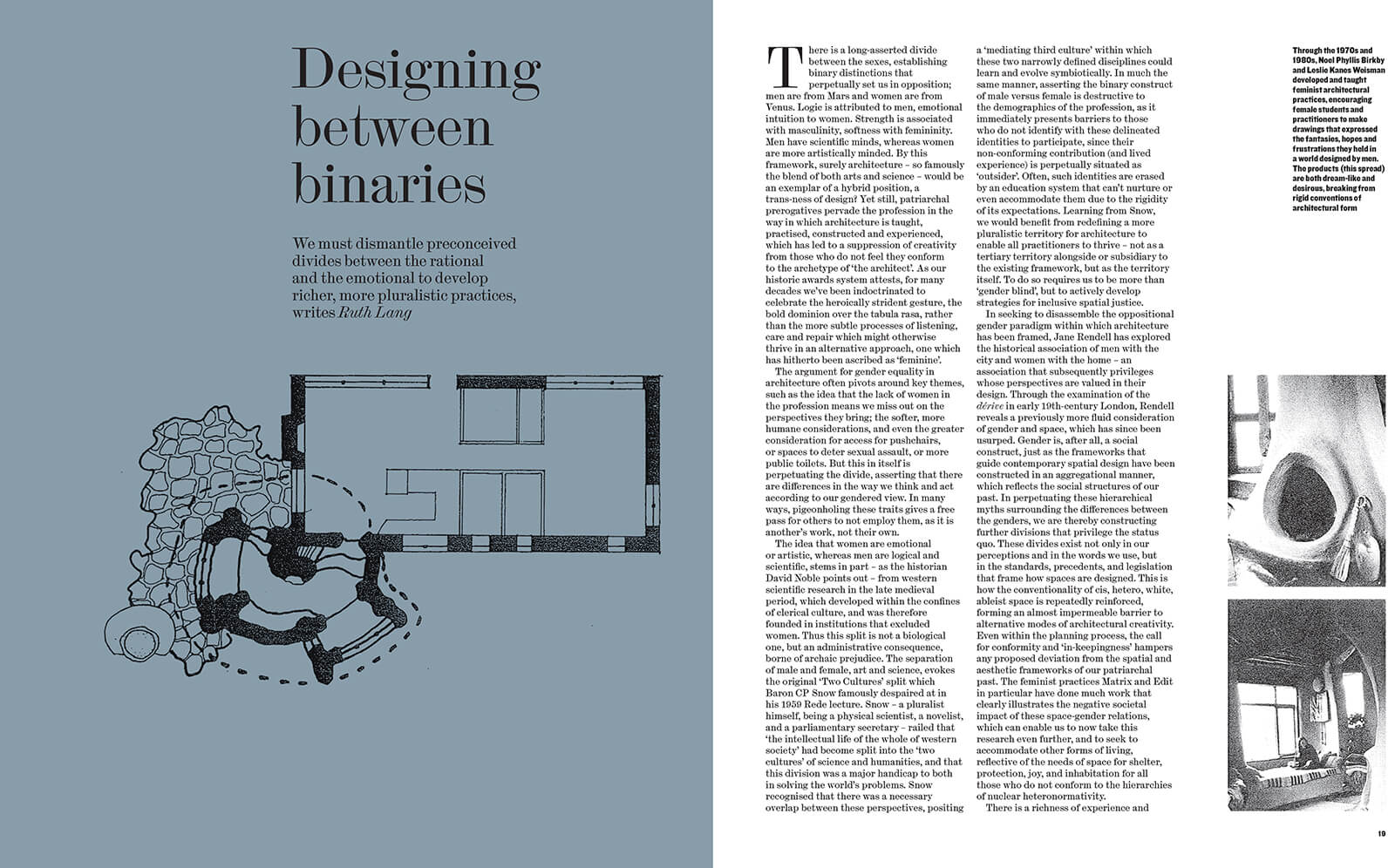

In her essay, Designing between binaries, consider what Lang writes: “There is a long-asserted divide between the sexes, establishing binary distinctions that perpetually set us in opposition... Logic is attributed to men, emotional intuition to women. Strength is associated with masculinity, softness with femininity. Men have scientific minds, whereas women are more artistically minded. By this framework, surely architecture—so famously the blend of both arts and science—would be an exemplar of a hybrid position, a trans-ness of design?”

In the book, the dynamic between ‘serious’ and ‘emotional’ architectures is succinctly studied, with the values of spatial experiences centred on being inclusive and ‘designed for,’ contrasting those that assert themselves and are primarily ‘designed by’; the variance between the prevailing ‘either/or’ relation, which can instead be approached with ‘both/and.’

I discussed with Marx the 58-page publication's examination of gender associations in architecture, the concept of 'emotional abundance,' and the possibility of a future where beauty and technical achievements are sought through commonality. The interview attempts to acknowledge, much like the book, a possible vision of contemporary architecture that draws from a fluid spectrum of experiences; one that loves, is sensitive, perceptive, and forgets to delineate; and how that might render progress vis à vis joyous, and wholistic spaces.

Jincy Iype: There is inherent value in seeking out and endeavouring towards a world of abundance, by all, for all, to all. Could you expand on this in the context of the monograph’s name?

John Jennifer Marx: In the title, the use of the word ‘Abundance’ is intentionally very gendered. The male perspective has for many centuries been one of scarcity and fear, and the culture of domination and self-interest that results from this. We wanted to invite people to consider moving towards a more feminine perspective, one of ‘emotional abundance.’ People often dream of happiness, which is a form of personal abundance, but we want to move beyond that, where both the individual and the collective can enjoy the benefits of, and in the creation of, cultural abundance. This is a ‘both/and’ sense of a balanced world. The hope is that a change in intention can have a profound impact on the future of humankind.

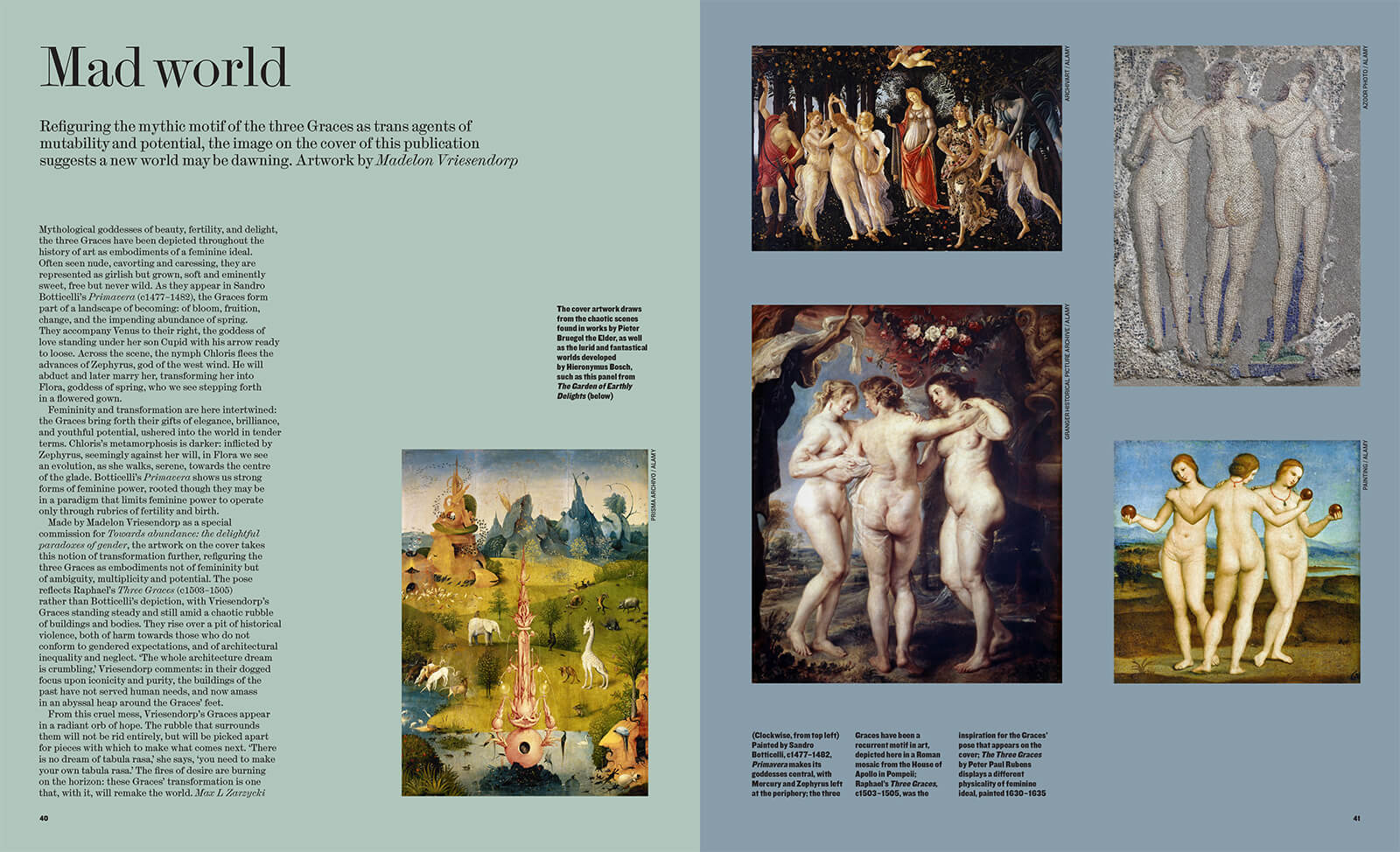

Jincy: How was the cover image chosen?

John: I had wanted the cover to be a painting of ideas. The Architectural Review (AR) suggested Madelon Vriesendorp, co-founder of OMA. The AR has a long history of working with the fine artist. I worked directly with Madelon for over a month to workshop ideas about what the cover should mean and what it should look like.

We started with a lone female figure, in a rather heroic pose, but this felt far too patriarchal in its singularity. We ended up with three figures, based on Raphael’s Three Graces, which allows us to play with the idea of gender provocatively. We also put a person of colour front and centre. Our inside joke is that we have to caution people who receive a copy to not walk into a high school in the US state of Florida unless they intend to get arrested.

Jincy: Who is the core audience?

John: We intended to reach several audiences, based on gender. This begs the question about gender itself. How many genders are there? Based on our research we found that many indigenous cultures believe there are at least five:

1. masculine males (normative-dominated)

2. masculine females (conditionally embraced)

3. feminine males (non-recognised)

4. feminine females (normative-not supported)

5. all of the above (outcast)

While that might seem to be a wide demographic range, most architects design within a very narrow, dominant masculine design approach and style. In that sense, there are two audiences:

With one, we intend to convince the dominant masculine design culture to look deeply into this narrowness and to open themselves to sharing with other voices different from their own, across not only gender but race and culture as well. With our other audience, we intend to inspire those repressed and marginalised, to celebrate the value and authenticity of their gifts and further, to find the true nature of their vision of design.

Jincy: Paradoxes are usually regarded as something to resolve—you describe them as ‘delightful’ on the monograph’s cover. Could you unravel this choice for us?

John: In the West, a common approach to a paradox is to attempt to resolve it. One curse of that viewpoint is the reductive binary of ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ I believe embracing paradox is a much healthier approach. Once you move away from ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ you might start to see the world as a series of balanced dynamics. For example, in architecture, a classic issue of firm type becomes, how much business is in balance with art, not picking one type over the other. This can oftentimes force resolution to take on a tone of morality, rather than promote self-expression and inclusion. I have found experiencing the world as a somewhat messy set of balance equations to be much more delightful, and the world then appears to be richer, fuller, and more colourful, than a simple black-and-white one.

Far less frequently are buildings praised for their sweetness, their grace, or how lovable they are. In a culture that tends to favour attributes associated with masculinity, a whole range of expressions has been repressed. – John Jennifer Marx

Jincy: Could you take us behind the arrangement of the book’s contents?

John: We largely designed the flow around a series of four paradox dynamics, and a few interventions of related content.

1. The Paradoxes of Modernism: The intention here was to describe the problems we face with modernism, and how opening design to a greater gender range can have a remarkable effect.

2. The Paradox of Vision and Collaboration: We intended to look deeply at how existing models of traditional design methods are currently changing, and how they might further change to create a more inclusive process and better outcomes.

3. Designers’ Perspectives: We invited six designers from around the world to discuss their gender experiences.

4. The Paradox between Self Expression and Belonging: This includes disassociating gender from the biology of sex.

5. Embracing Paradox: Here, we looked at how changing from resolving to embracing paradox can result in a healthier worldview.

Jincy: There is something to learn and gain from being in the in-between spaces of a largely dominant binary culture, a viewpoint that Towards Abundance leans heavily towards.

John: One of the most beautiful revelations that came from the process of working on this project was that I think the ‘in-between spaces’ of gender is where the future lies. Where we fall in the gendered spectrum of the loosely borrowed Jungian concept of Anima-Animus, which is the notion that each gender's psyche contains vital elements of the other. Without these elements, one will become out of balance. Worse still is to repress those aspects of the other gender.

I have found that when I rebalance my sense of gendered elements to live in the in-between spaces, my creativity and connection to the whole of the world improve dramatically. The repressive binary cultures we currently live in are constantly trying to fit one back into a pink or blue box. I feel this is an additive process, I enhance my humanity by exploring and adding feminine qualities to my male side. To aspire to be fully gendered… rather than non-gendered. There was some debate on this topic—not everyone agreed on this perspective. We felt that dissent is healthy.

Jincy: Designing between or beyond conventional binaries requires systemic learning and in equal measures, plenty of unlearning. How does one even begin to venture into this?

John Jennifer: Working on the monograph with the AR team was, in itself, a learning and unlearning process. While the topic of gender has been a fundamental issue since the dawn of humanity, only recently have we, in the West, begun to challenge gender norms in a public way. We engaged in many deeply passionate debates about every issue brought up in the book. It was interesting that there was much we disagreed about, which we all considered to be a very healthy condition, as we are only beginning to scratch the surface of these issues.

Is there a biological basis for gender?

How many genders?

Jincy: What was your process of selecting contributors for this collection of essays, and how were they briefed?

John Jennifer: The process began with Manon Mollard, the editor of Architectural Review (AR). She and I set a series of high-level goals and aspirations, [and] shared a desire to explore what an ‘advocacy monograph’ might mean relative to contemporary publishing. Once we had established a broad outline, Manon suggested I work with a young editor on the staff at the AR named Max Zarzycki.

Our first step was to outline in detail the major themes we wished to address. We then proceeded to create a detailed request brief delineating the specific topics we wanted each writer to speak to. One of the most rewarding aspects of working with the AR is the quality of writers with whom the AR has deep relationships [with]. Max and I created a rather long list of potential writers, whose work was known to us and the AR. We looked to find a broad range of geography, and demographics to ensure our collective efforts were global and inclusive. Max then facilitated reaching out to individual writers to discover their availability.

Interestingly, there was some difficulty in finding writers willing to write provocatively on the topic of gender. I am still unpacking why this is.

Jincy: How did your journey of becoming an architect, artist, and poet bring Towards Abundance to fruition?

John Jennifer: Oh my, this journey started when I was 13. That moment when American culture demands you fit into the blue box or the pink box, depending on your biology. You are not given a choice in this. At that moment I started to encounter what is now known as ‘toxic masculinity.’ While I rejected this wholeheartedly, I was still forced into a normative blue box. There are some very positive qualities within the blue box, but it is quite limiting. I felt I was missing out on half of humanity.

In 2020, I decided to publicly embrace my twin-gendered nature, and I have been making up for lost time, including advocating for a shift in design culture away from a mono-gender perspective towards a full-gender perspective of inclusivity and care. At some point, I decided I wanted to write about this.

I had done a prior advocacy monograph with the AR called The Absurdity of Beauty. I knew from working with Mollard and former editor Cathy Slessor, that the AR would be a supportive and passionate publisher on this topic. The AR has also been at the very forefront of promoting women and non-binary genders in design. They lived up to that in every possible way.

Jincy: Lastly, what does an ideal architecture of abundance look like?

John Jennifer: It would involve a change in intentions, rather than a specific visual reference.

If we look over the past 100 years, austere and minimalistic architectures have been revered for their poetry and their power. Far less frequently are buildings praised for their sweetness, their grace, or how lovable they are. In a culture that tends to favour attributes associated with masculinity, a whole range of expressions has been repressed: if the first century of modernism can be considered an architecture of abstraction and ideas, what might we design if we turn our attention to an architecture of emotional abundance?

To go further we should discuss what makes for ‘lovable’ architectures. Whether beautiful, caring, humane, or comforting, the definition of ‘lovable’ encompasses a whole range of interpretations—delightfully subjective, but all crucial to understanding in building a more equitable and expressive future. An architecture of abundance is less a case of defining what ‘lovable’ is as a singular style, but rather in offering the provocation, "What would lovable mean to the individual architect?" I would much rather see what a million designers would create with a lovable intention.

Towards Abundance is an important book—for those who recognise the patriarchal aggression prevalent in the architecture and design industry and for those who do not. It is a motivation to embrace and adjust to differences, emphasising that disagreements and discussions are naturally beneficial, and that beauty can be discovered in pluralistic narratives, to lean into the messy, glorious ambiguity that is the creative human experience.

I leave you with words from one of Marx’s essays, Paradox between collaboration and vision, and from Nathaniel’s Unbound Expressions, sharing their vision and agency:

“We have, in this moment an opportunity to deeply look at the process, structure, and values of design. We can evaluate and disrupt the normative patterns of aggression, heroism and arrogance that follow from a masculine male prerogative and condition of privilege—one that we have been trained to believe is universal and sacrosanct. Most importantly, we have the opportunity to engage and embrace the alternative perspectives of the majority of people whose voices have been excluded. From this, we may be able to find a more humane path forward.”

“Let’s create cute architectures, adorable architectures, loveable architectures, kaleidoscopic architectures, soft architectures, let’s make polyamorous and genderqueer cities that are wild and sensual, sensitive and kind and welcoming.”

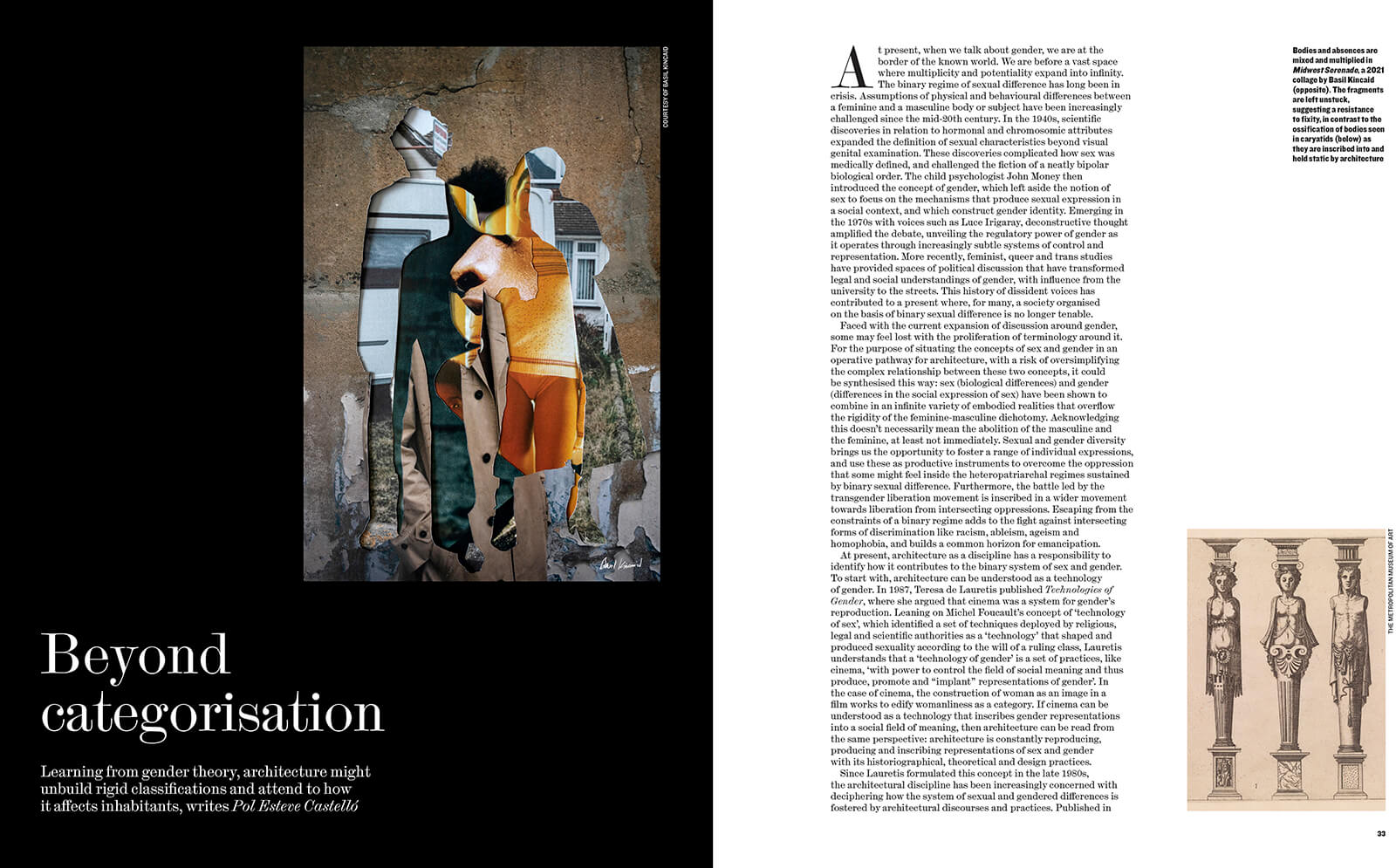

Three essays from ‘Towards Abundance’ can be read in full on The Architectural Review’s Gender and Sexuality page: ‘Unbound expressions’ by Adam Nathaniel Furman, ‘A woman seeks room in London’ by Jessica Andrews and ‘Beyond categorisation’ by Pol Esteve Castelló.

The monograph’s digital edition can be purchased from the AR’s online shop.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 12, 2026

The New Government Quarter by Nordic Office of Architecture reimagines the site of the 2011 terror attacks as a porous civic district shaped by architecture, landscape and art.

by Bansari Paghdar Mar 11, 2026

Conceived by Pentaspace Design Studio, this cuboidal volume of exposed concrete and glass pegs movement as integral to the learning experience.

by Pranjal Maheshwari Mar 07, 2026

Designed at the threshold of cultural preservation and rapid urban growth, the museum references geology, history and cosmology to create a global tourist destination in Medina.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 05, 2026

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Bruce Goff: Material Worlds moves beyond architecture to reveal the curiosity and cultural influences that shaped the American architect’s work.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Jincy Iype | Published on : May 02, 2024

What do you think?