Lygia Clark at Whitechapel Gallery: Engaging Bodies and Performing Freedom

by Deeksha NathOct 19, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Hili PerlsonPublished on : Jul 10, 2025

For the first time in its history, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam—world-famous for its collection of Dutch Masters, including Rembrandt’s Night Watch—has handed the reins of an entire exhibition over to a contemporary artist – the Indonesian-born, Dutch-based Australian artist Fiona Tan. But rather than simply showing her own work, Tan performs a curatorial sleight of hand that feels at once subversive and quietly reverent. The exhibition results from the artist’s sustained research into the history of psychiatry, reassembling the field’s cultural and visual legacy through a deeply humanistic lens. The word ‘monomania’—now obsolete in clinical usage—once referred to obsessive, singular fixations. In Tan’s hands, it becomes a metaphor for the museum itself.

Her inquiry began with an artwork: Théodore Géricault’s Portrait of a Kleptomaniac (c. 1822), which she first encountered in the early 1990s, not in a museum, but through an essay by John Berger. Writing on a Géricault retrospective at the Grand Palais, the eminent British art critic described the portrait’s raw compassion and its confrontation with the “madness of the modern world”. The image, and the ideas surrounding it, stayed with Tan for decades. As a young artist studying painting, she was struck by the portrait’s immediacy—“The hand knows what to do,” she describes to a group of journalists at the opening—and the way Géricault seemed to paint without judgment, simply seeing and recording a human being with dignity and presence. It became the conceptual seed of Monomania, which performs a rigorously poetic excavation of 19th-century pathologies and the ways visual culture has served to codify, diagnose and contain the excesses of human emotion.

From Géricault’s Portrait of a Kleptomaniac, possibly painted in a Paris hospital according to Tan’s research-based annotations, the exhibition spirals outward, not unlike the obsessions it stages. One gallery is dedicated to Baroque painter Charles Le Brun’s 17th-century engravings of expressive facial types—a grotesque taxonomy of passions that, in its cold certainty, prefigures phrenology. Another features a room of contorted bronze busts by Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, whose late-life descent into ‘affective’ portraiture has been both pathologised and lionised. Tan doesn’t resolve this contradiction. Instead, she leans into it, surrounding the busts with mirrors and slow ambient audio, transforming them into oracles of psychic disarray.

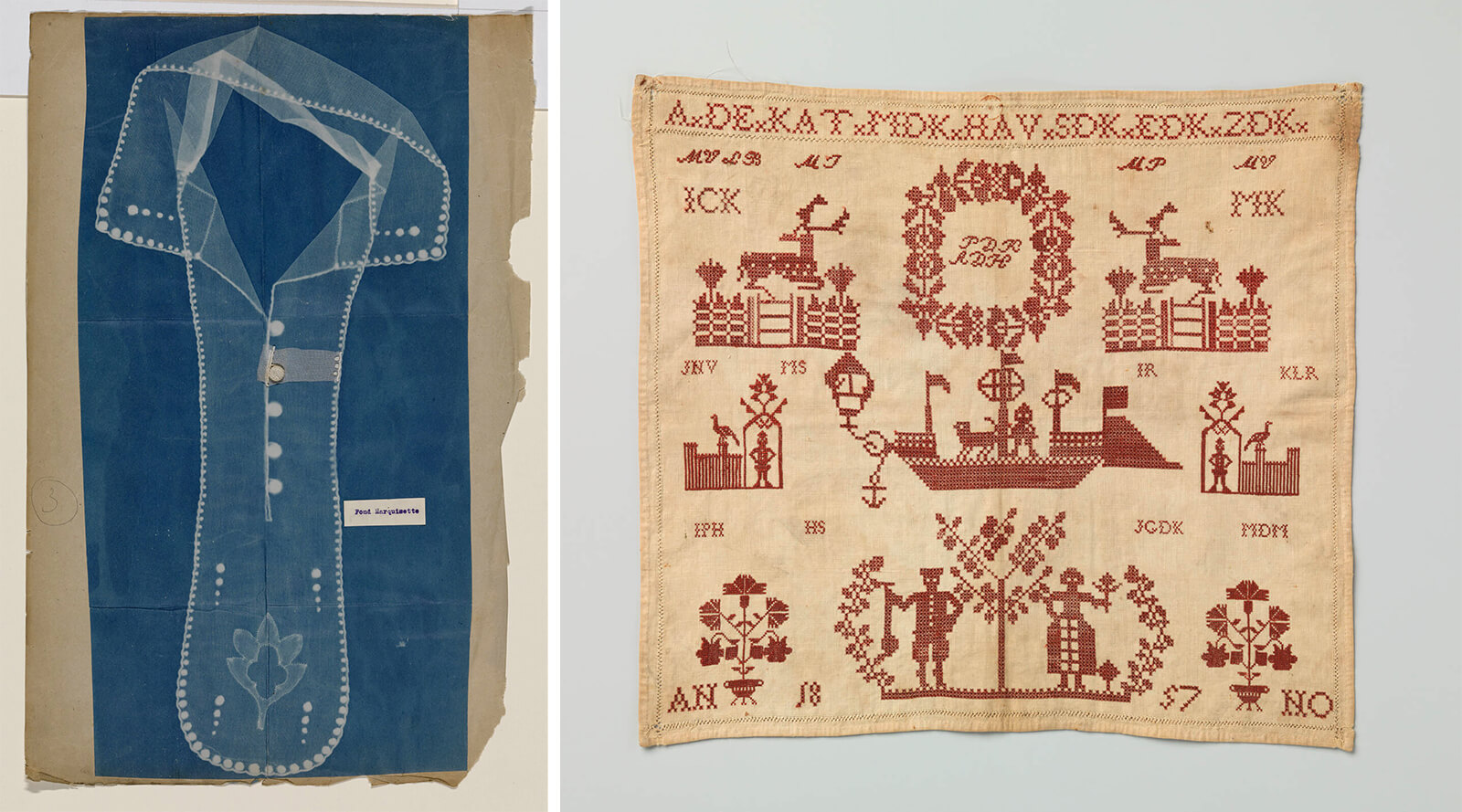

Stitching together 270 objects, the exhibition draws on overlooked items from the Rijksmuseum’s own holdings and key international loans, including medical manuals, anatomical mannequins, ritual masks, timepieces and textiles. Embroidered linen from 1857, adorned with letters and simple motifs in red silk, emerged from Tan’s research into the lives of 19th-century female psychiatric patients in the Netherlands. Every girl was required to make one—same letters, same symbols, same moral instruction—but each embroidered linen subverts that uniformity. There are also several new works by Tan on view, including two major video installations. But to see her contribution solely in those would be reductive; her meticulous research and the personal annotations she’s written for each object—collected in a small paper guide—form a major work in their own right.

Among the most resonant inclusions are several prints from Francisco de Goya’s Los Caprichos and Los Disparates series. These etchings—distorted, surreal and laced with bitter satire—serve as a psychic counterpoint to the clinical rationalism found elsewhere in the exhibition. In The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1799), a figure slumps over a desk while bats and owls swirl overhead—a now-iconic image of the unconscious unshackled, reason undone. Tan positions these works not merely as historical artefacts but as visualisations of psychological disturbance long before psychiatry codified such states. Goya, like Tan, understood that madness is as much a social construct as a personal affliction—and that the most terrifying monsters often reside in the mind of the observer.

The show’s cumulative logic is built on startling juxtapositions. A vitrine of medical paraphernalia—restraints, early EEG-like instruments, surgical drawings—sits near delicate Japanese Noh masks, their carved wooden visages suspended like mid-scream spirits. There’s a sequence of photographs from the West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum archive, each labelled with dated diagnoses (‘hysteria’, ‘religious mania’); then, there’s an installation of suspended christening gowns associated with the trial of Henriette Cornier, an infamous 19th-century French maid who was deemed a ‘homicidal monomaniac’ for murdering a toddler in a horrific manner. Declared insane in 1827, her diagnosis was the first time in history that a psychiatric evaluation was used in a court of law, and Cornier was spared the death penalty.

But this is not simply a show about madness. It is also about the field of psychiatry itself, and regulations concerning the rights of patients, some of which are still in effect today. It is also a show about systems of knowledge: how institutions categorise, order and aestheticise behaviour. The museum itself becomes a metaphor for this pathology of classification. By placing devotional objects beside forensic sketches and pairing art history with legal evidence, Tan creates a semantic instability. In one gallery, a wall-mounted timeline of historical monomania cases runs parallel to a display of rare 19th-century self-help manuals and spiritualist treatises. The impression is of a society frantically trying to make meaning from the opaque and the interior—a compulsion that feels eerily contemporary, and open-ended.

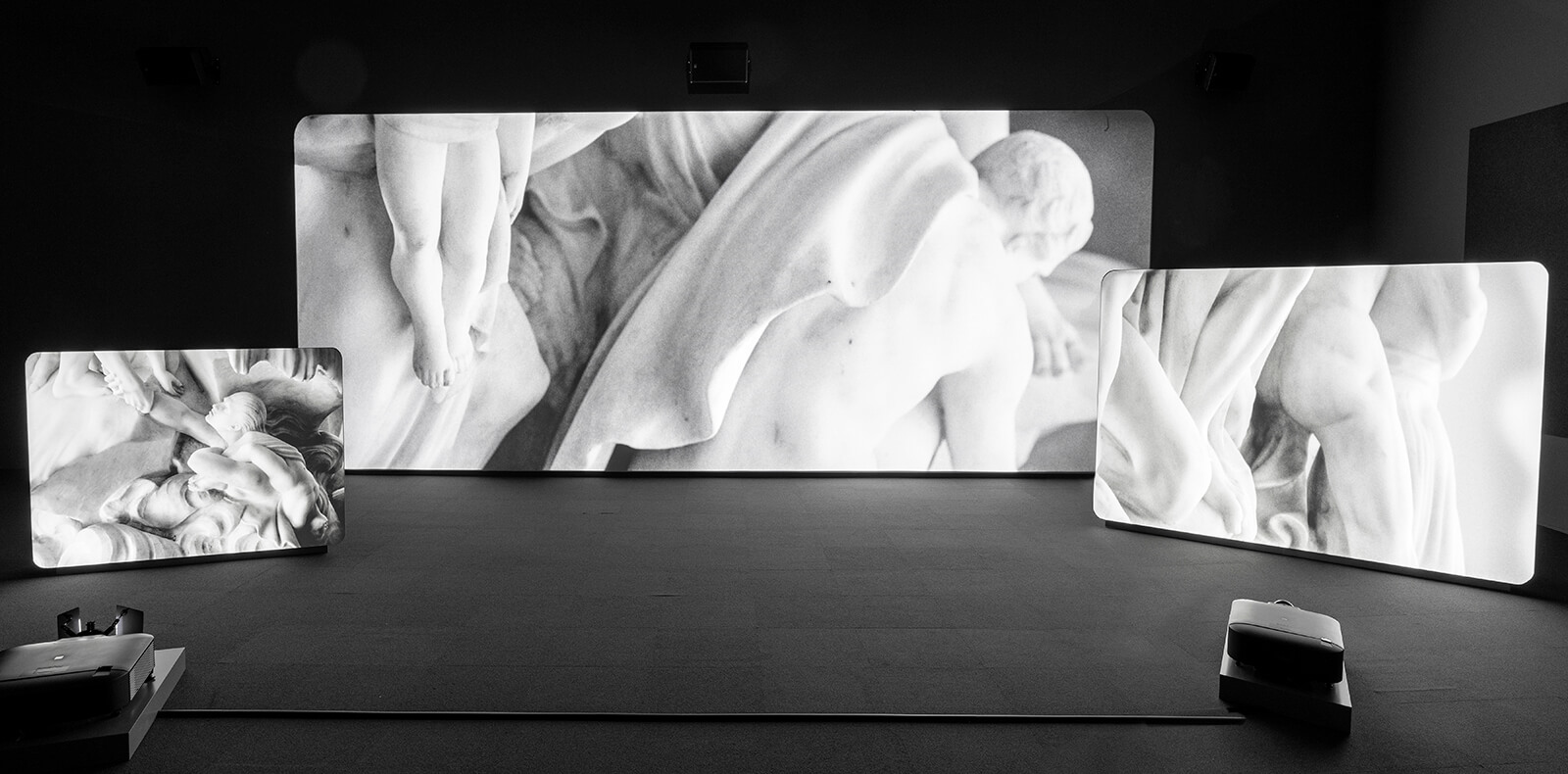

Tan’s own works, carefully woven into the flow of the exhibition, serve as critical punctuation marks rather than focal points. Pickpockets (2020 – 21) reanimates mug shots of 19th-century petty criminals through fictional monologues voiced by actors. Rendered in luminous monochrome on adjacent screens, these figures become avatars of lives shaped (and erased) by bureaucratic systems. In Janine’s Room (2025), a multichannel video installation commissioned by the Rijksmuseum, a woman reads and writes obsessively in a claustrophobic study. Inspired by a character from W. G. Sebald’s Vertigo, the piece unfolds as a slow-burning allegory of entrapment, where intellectual rigour blurs into emotional fragility. Sand falls steadily onto her papers, marking both the passage of time and the quiet erosion of meaning—what now seems urgent will eventually become artefact, perhaps even collectible. It’s the show’s most cinematic moment, and its quiet intensity is devastating.

If the exhibition has a weakness, it may lie in the tightness of its conceptual loop. Monomania resists digression; it does not loosen its grip. This is not a show designed to dazzle, nor one that seeks visual resolution. There are a few ‘masterpieces’ here, no crescendo of iconic works. Instead, the exhibition builds its power through accumulation, repetition and slow revelation. Tan wants us to sit with discomfort, to question the lens through which we judge sanity, beauty and truth.

In doing so, she transforms the museum into a site of moral and epistemological inquiry. As viewers, we become complicit archivists, sorting through traces and fragments of lives that were once labelled deviant or diseased. The deeper one moves into the show, the more porous the boundaries between curator, artist and clinician become. In an era of spectacle-driven blockbusters and formulaic retrospectives, Monomania is a rare thing: a museum exhibition that dares to ask why we exhibit at all. Through the lens of madness, Tan has staged a meditation on the limits of reason, and on the haunting persistence of the unknowable in human life.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its editors.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Hili Perlson | Published on : Jul 10, 2025

What do you think?