Art Dubai 2025 honours collective identity, spotlighting eco-social urgencies

by Samta NadeemMay 07, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Giulia ZappaPublished on : Dec 12, 2024

A small yet illuminating exhibition, niched within the permanent collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, aims to shine a long-overdue light on a blind spot in the history of art. Lithuanian Contemporary Art from the 1960s to Today: A Major Donation, organised in partnership with the MO Museum in Vilnius, celebrates a series of works given by the MO Museum’s founders, Danguolé and Viktoras Butkus, to the Pompidou's collection. More importantly, the exhibition offers a unique opportunity for visitors to reflect on the richness and complexity of an often-neglected artistic legacy.

Winners make history, historians often remind us, highlighting that the presence of military or political dominance not only asserts tangible hard power but also exerts a profound soft power – shaping perspectives on history and, at times, distorting it. The history of art is no exception to the influence of geopolitical forces. Most colonial powers imposed European canons on local artistic expressions, marginalising cultural heritages by dismissing them as mere folklore. Similarly, under regimes driven by rigid political ideology, artistic relevance was often dictated by one's adherence to the prevailing worldview, with specific styles elevated to the only acceptable form of art.

In 1990, Lithuania’s newfound independence marked the beginning of a transformative era for the country’s artistic landscape…an openness to international influences breathed fresh life into Lithuanian art, paving the way for previously prohibited forms of expression, such as performance art and new media.

The Soviets were no exception. Guided by Marxist ideology, Soviet occupation across Eastern Europe and Baltic countries reinforced socialist realism as the sole artistic language to represent the proletariat’s vision and struggle for a just society. Russians imposed strict censorship of national cultural symbols and the suppression of artists exploring alternative expressions. In Lithuania, a nation that had only gained independence in 1918, Soviet annexation after World War II brought deep collective and individual suffering, vividly reflected by the works displayed in this exhibition.

In this repressive context, noncompliant artists began using metaphors and biblical allegories to convey forbidden messages, as several works in the exhibition poignantly demonstrate. Vincas Kisarauskas’ 1966 work Sūnus Palaidūnas reinterprets the gospel parable of the 'Prodigal Son' with abstract figures, a father and a son, defined by angular forms and a restrained colour palette of deep reds and browns. The uncertain, hesitant encounter between father and son becomes a poignant metaphor for Kisarauskas’ own struggles during this period, marked by a lack of artistic recognition. Around the same time, Leonas Linas Katinas developed a deeply personal visual language, combining abstract and naïve drawings with symbolic elements. In his work, Pirštas (1971), a dark, uniform underground landscape features a door flung open to a parallel world, where vibrant blues and greens symbolise a connection to life, hope and transcendence amidst oppressive surroundings. In Aikštėje (1975), Marija Teresė Rozanskaitė captures a profound sense of desolation through a partially figurative depiction of a body lying on the ground, seemingly overturned and lifeless. The work evokes the desecration of Lithuanian graves by the Soviets during the civil war that gripped Lithuania from 1944 to 1953. Encircling the fallen figure is an abstract background rendered with mixed media, where Rozanskaitė demonstrates a strikingly contemporary sensibility. Using humble materials like burlap, mirrors and wood, she crafts a subtly evocative setting that heightens the emotional resonance of the figure.

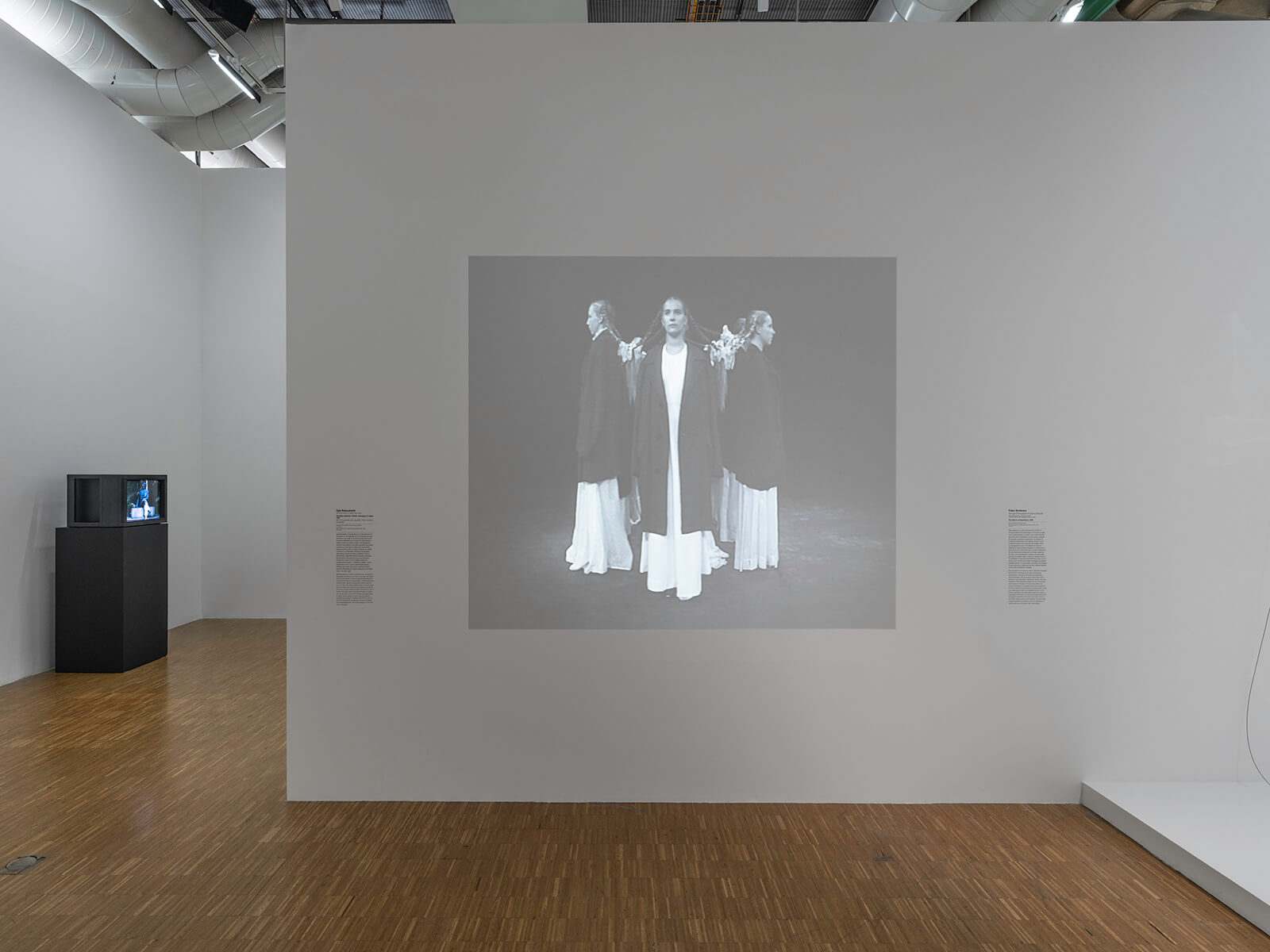

In 1990, Lithuania’s newfound independence marked the beginning of a transformative era for the country’s artistic landscape. As the works in the exhibition reveal, openness to international influences breathed fresh life into Lithuanian art, paving the way for previously prohibited forms of expression, such as performance art and new media. At the same time, the lifting of censorship prompted a deeply introspective and often painful reckoning with collective history, while also raising new and open-ended questions about the future trajectory of Lithuanian society. Eglė Rakauskaitė’s 1996 video Be kaltės kaltiems. Pinklės. Išvarymas iš rojaus (For Guilty without Guilt. Trap. Expulsion from Paradise) is one of the most striking works in the exhibition; it vividly captures the tension between the struggle for self-determination and the disillusionment of a present that can no longer be idealised but is instead burdened by new challenges and fears. In the video, 13 adolescents dressed in virginal white stand in a circle, their braided hair interwoven, symbolising a unified, almost symbiotic bond. One by one, the girls detach themselves, breaking free and stepping into independence. These first steps toward autonomy, however, also signal the dissolution of their shared unity, marking the fragile balance between personal freedom and social cohesion.

What does a country become when it is no longer united by the presence of a common enemy? How likely is it that collective consciousness will give voice to the abuses of the past, or instead, be swept up in a blind enthusiasm for the illusions of the present? In this context, is a contemporary artist inevitably called to reflect on his or her cultural identity? From an artistic perspective, does the newfound freedom to explore one's cultural heritage necessarily lead to a deeper examination of national identity? And does the renewed connection with Europe inevitably translate into an exploration and adoption of European - particularly Western European - cultural codes? The exhibition offers no straightforward answers. In Emilija Škarnulytė’s video The Footstones in Night Writing (2015), the artist’s blind grandmother tenderly caresses the faces of old Lenin statues, as if tracing the contours of her past. By contrast, in Anastasia Sosunova’s Agents (2020), the artist seems to express a conspiratorial view of folk art through her characters, seeing it “as if it were a Trojan horse, developed unnaturally, imposed and instrumentalised by different parties”.

It is difficult to pinpoint where a country with a long history but recent independence decides to position its expressive focus. As is often the case, art proves more compelling for the questions it raises than for the answers - never definitive - it attempts to impose. What the thematically and linguistically diverse variety of works on display seem to suggest is that the multiple discourses within Lithuanian art tell the story of a transition completed: one toward a contemporary scene that moves beyond rigid rules and predetermined guidelines, embracing pluralism and empowering singular voices to assert themselves.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its editors.)

by Ranjana Dave Oct 03, 2025

Bridging a museum collection and contemporary works, curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath treat ‘yearning’ as a continuum in their plans for the 2025 Taipei Biennial.

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

by Hili Perlson Sep 26, 2025

The exhibition at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus unpacks the politics of taste and social memory embedded in the architecture of the former East Germany.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Giulia Zappa | Published on : Dec 12, 2024

What do you think?