Exploring the work of 10 Olympian artists ahead of the 2024 Summer Olympics

by Manu SharmaJul 24, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Ranjana DavePublished on : Aug 09, 2024

This weekend, 16 b-boys and 17 b-girls will compete in men’s and women’s competitions at the Paris Olympics, going up against each other in one-on-one ‘battles’. Breaking is a genre of street dance, and an early component of hip hop culture, first originating in the 1970s in New York as a means of expression for Black and Hispanic youth. What began as a community practice in the Bronx, a socially and economically disadvantaged borough in New York City, soon became a visible marker of hip hop culture, with crews, groups of young, often self-taught dancers, popping up in cities and towns across the world. Hip hop offered an accessible toolkit of building blocks in music, speech and movement, allowing these groups to articulate complex experiences of marginalisation, oppression and resistance. Over time, hip-hop music has found commercial success – its global popularity translating into visibility for other hip-hop subcultures. Breaking’s inclusion in the list of Olympic disciplines for Paris 2024 has given it a significant boost, inviting recognition and support from national sports federations and sponsors.

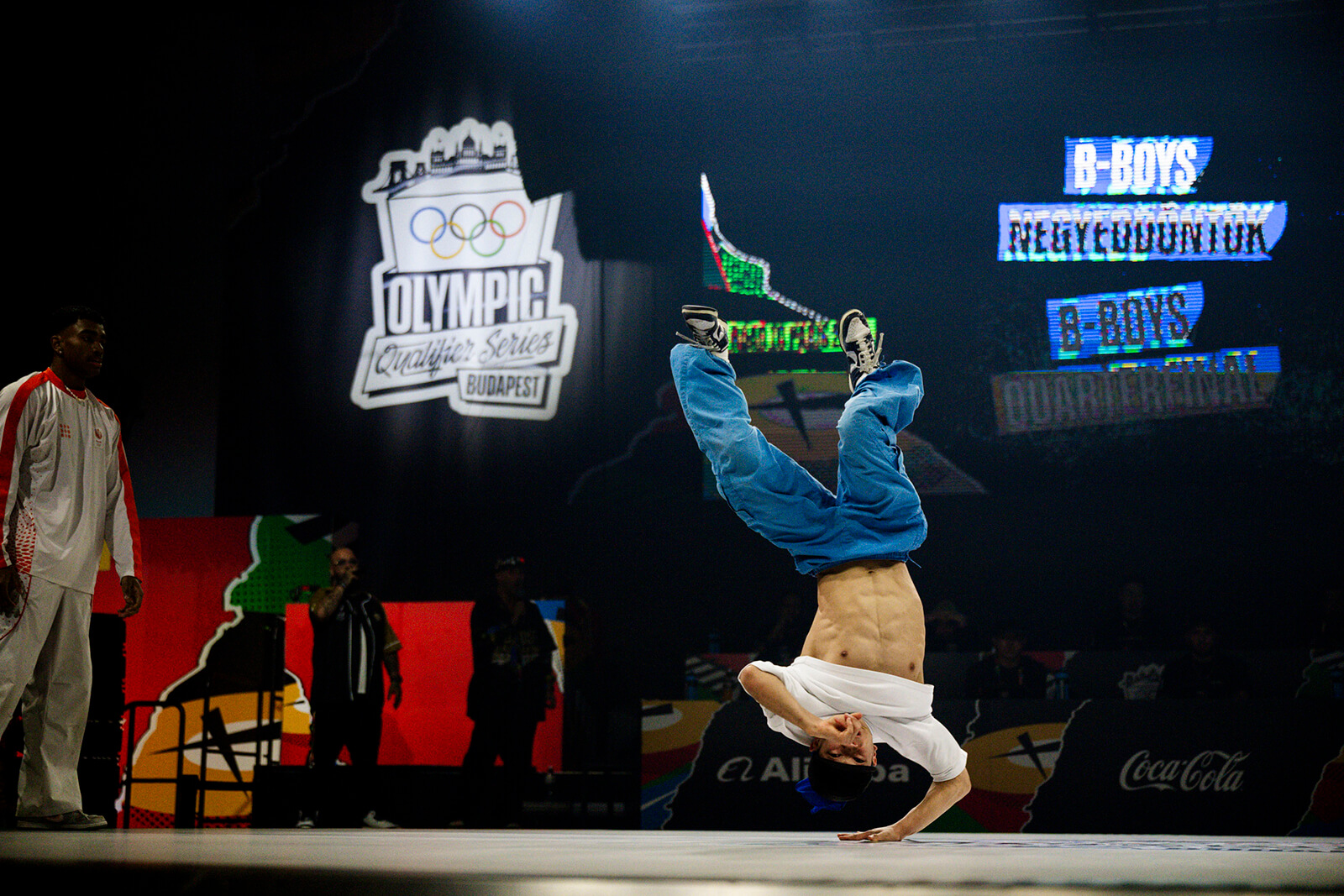

Is breaking an art or a sport? Are the competitors dancers or athletes, or both? At the Olympic qualifier in Budapest in June 2024, a DJ was playing copyright-friendly music, and judges went by mononyms like Virus and Intact. In its avatar at the Olympics, breaking is assessed on highly subjective criteria. Competitors in a battle take turns to perform in individual segments called throwdowns for 60 seconds each. There are four broad sections to each routine: top rock – performed standing up, it is an introductory set of movements that the breaker uses to ease into the routine; down rock – a mixture of floorwork and footwork that makes up the bulk of the routine; power moves – flashy acrobatic phrases where dancers spin on their heads or hands and freeze – static and complex balances that competitors use as signature phrases.

To understand breaking’s new innings, I watched Japanese B-girls Ami (Ami Yuasa) and Ayumi (Ayumi Fukushima) battle for first place in the finals of the Budapest qualifier. As the comperes worked the crowd, both athletes paced the fringes of the stage, with Ami trying out a few preparatory hops to warm up. 41-year-old Ayumi, one of the oldest B-girls on the competitive scene, was the first to perform. She immediately threw down the gauntlet, trotting towards her opponent with outstretched arms. Ayumi quickly descended to the floor, executing a dynamic down rock section with explosive spins and arm and head balances. Ami was equally assertive in her response, performing power moves with impeccable execution and lightness, including an inverted sequence where she twisted and untwisted her legs while balancing on her head. At the end of the battle, the comperes counted down to the scoreboard lighting up; Ami won two of three rounds and was awarded first place.

Breaking stirs up the same dilemmas as other virtuosic and performative Olympic disciplines—figure skating, gymnastics, and artistic swimming among them—where an athlete’s score is tied to their technique and execution, leaving room for subjective assessment. In the Olympic balance beam final at Paris 2024, star gymnast Simone Biles was penalised for an “improper salute”; her arms were aloft in the position that gymnasts begin and end their routines with, but the judges didn’t think she had saluted them adequately enough, or with the right spirit. Often, these understandings of technique and execution may also lie in cultural associations of ideal body types in a sport – the Black French figure skater Surya Bonaly, known for her athleticism, was often left off podiums in the 1990s, in a sport that has long idealised thin and balletic skaters.

Breaking is so free; you can dance on your feet, you can spin on your head if you want to. So I can always express my feelings and thoughts when I am on the stage. – B-boy Shigekix in a video on the Olympic Games website

Breaking’s big moment has not been without controversy – its categorisation as a sport with Olympic medals on offer has meant that there is a greater emphasis on difficult tricks and individual glory, obscuring breaking’s cultural origins and its importance as a community-based practice. To an extent, perhaps its cultural significance translates into embodiment. In a video posted on the Olympic Games website, Japanese B-boy Shigekix, a podium favourite, said, “Breaking is so free; you can dance on your feet, you can spin on your head if you want to. So I can always express my feelings and thoughts when I am on the stage.”

But on the Olympic stage, even this freedom must be rehearsed. Competitive breakers, used to a more relaxed environment, are now training like athletes, with a regimen that includes strength training, rest and rehabilitation. Their onstage appearance—slouched shoulders under loose and baggy sweatshirts—belies their conditioning. When Shigekix discusses his training routine, he says it’s mostly breaking practice, but also some cross-training, which fosters his explosiveness and versatility. Breaking battles are inherently interactive and situational environments – where vibes matter as much as training and skill do. In a battle, breakers face each other on the circular stage, while the crowd converges around them. Their performances are a call-and-response game. When they dance, they use rhythmic accents to make a point, making sure that their opponents recognise the force of their response. There’s no tuning out, even when they’re not dancing. They’re constantly watching their opponent, showing appreciation for power moves with a cold detachment that seems to say: “That’s amazing, but I’m even better.”

In Paris, some of breaking’s biggest medal contenders come from Japan, Australia, Lithuania and Kazakhstan. The internet has aided breaking’s popularity; aspiring breakers in regions without a breaking culture turn to YouTube to learn new tricks and skills. At Paris 2024, the women’s competition includes Afghan B-girl Manizha Talash, who is on the Refugee Olympic Team. Talash took to breaking as a teenager in Kabul, where she was the lone woman on a 56-person strong breaking crew. She fled Afghanistan in 2021 after the Taliban takeover, and was eventually granted refugee status in Spain, which allowed her to explore competitive opportunities in breaking.

Recent inclusions at the Olympics include skateboarding and BMX racing - both disciplines that first emerged as urban subcultures. Breaking may be a one-Olympics wonder; it is not yet on the list of sports for the Los Angeles Summer Olympics in 2028. Yet, it gestures to the possible future of the Games, which is making slow attempts to keep up with the times in an effort to engage younger audiences. Perhaps the arrival of breaking on the Olympic stage echoes its past – because until 1948, the Olympics also included an art competition, with medals awarded to the winners.

Paris 2024: Explore STIR's extensive coverage of the Olympic and Paralympic Games through features, insider interviews, and thoughtful insights across architecture, design and art, to find out how the global sporting event engages the French capital across these creative avenues and beyond.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its editors.)

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

by Ranjana Dave Oct 03, 2025

Bridging a museum collection and contemporary works, curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath treat ‘yearning’ as a continuum in their plans for the 2025 Taipei Biennial.

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Ranjana Dave | Published on : Aug 09, 2024

What do you think?