India Art Fair 2026 and more in Delhi: The STIR list of must-see exhibitions

by Srishti OjhaFeb 04, 2026

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Rosalyn D`MelloPublished on : Mar 27, 2024

If I could summon one person into my kitchen right now that person would be Wenceslaus Mendes. Until recently, I had no clue of his existence. A newsletter from the Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation announcing his receipt of the Mrinalini Mukherjee Creative Grant 2023-2024 brought him into my purview. It took just one line for my interest to be aroused—Mendes will be developing his project kalchi kodi—a fish curry and rice story under the grant.

It simply is not every day that a Bombay Goan art critic like me reads a press release from the art world centring the words kalchi kodi. Growing up Goan in Mumbai, this everyday staple was the premise of our identity. My father would make the masala for the curry and store it in little plastic boxes—used Amul cheese dabbas mostly—defrosting them almost every day or every alternate day for our meal. The kokum floating in the curry looked like the fins of sharks. Even when the prawns or the fish were eaten, the leftovers would be stored in the fridge and re-heated the next day. I learned early on that our cuisine is a slow-cooked affair. We marinate our meats and fish, make the masalas and cook everything together. Yet, almost every dish tastes better the next day. Kalchi means belonging to yesterday and the kodi is the curry. Xitkodi [pronounced Sheetkodi] refers to our staple meal—curry rice. The vegetable element was frequently in the curry—in the form of okra or drumsticks. During summer, you were assured of finding pieces of raw mango floating inside too. The last time I had one of those ahamoments around kalchi kodi was at the restaurant Pedro’s in Mumbai. The late chef Floyd Cardoz had a butter infused with kalchi kodi that I thought was so brilliant on the menu. The second aha moment was reading about Mendes’ winning project.

Given that at the crux of my writing practice are my own embodied investigations into the subject of leftovers—which I understand as an ancestral Goan inheritance—learning about another Goan whose practice seemed similarly rooted in its metabolic connotations filled me with a specific kind of intellectual joy. I had to interview Mendes to learn more about why he does what he does. Luckily, he acquiesced to my request for a dialogue over email. Edited excerpts follow. To read Mendes’ writings on food, extractive mining and collaborative practices, look up his page on Academia.

Rosalyn D’Mello: How would you describe your artistic trajectory, especially as someone who graduated in philosophy?

Wency Mendes: The root of the word ‘art’ is techné, ars and poiesis, which means to make knowledge. The propositions of ‘art’ and ‘artist’ invariably suggest a rigid structure of power. While I understand this, I choose not to subscribe, proliferate or propagate this. I come from an apprentice model of learning and working with film and a lens-based practice. Although this comes from an industrial mode of production, here [with film] we work together as the labour (within its structures of power). Yet, each individual is critical towards working on the whole, without which there is no film. So, in this sense, my practice emerges from collaboration. I construct this as ‘co-labour-abling’ and this becomes non-hierarchical, rhizomatic-plural, fluid and multi. This allows me space to breathe and work.

Rosalyn: Could you tell me about the genesis of kalchi kodi and how it relates to indigeneity?

Wency: Fish-curry and rice first emerged as an essay outlining my statements on originality, ethics, knowledge production, etc., for my master’s dissertation [at Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University Delhi]. During my Masters, food emerged [for me] as a medium, an expression of sensoriality, knowledge, memory and lived experience. The sensuality of food has created deep imprints for me as it triggers memories of growing up between Goa and Bombay [Mumbai]. The additions, editions, substitutions, omissions and erasure of recipes and food, the feeling of community and belongingness impact us as individuals and as a society, too (ecologically, socio-culturally, economically and politically). Kalchi kodi is not this iconic fetishised dish, it is the simple leftover from the day prior that is eaten in most coastal homes, rich in memories as we quibble and share the last piece of yesterday’s fish, or, for me, the dried mango seed. And yes, this curry ferments and pickles because of its salt. It sours and spices overnight and thickens at the bottom of the pot through reheating, which changes, refreshes and deepens its flavour.

Food and sensoriality become extremely powerful mediums of connecting within our environment and, more importantly, are sites for resistance and resilience. Again, these sites are geospatial and temporal. Environmental degradation and climate change impact ‘local’ communities on the ground. Today, development models premised on changes in technology have an impact on ecology and climate change, thereby altering the environment, community and lived experience. Kalchi kodi is an attempt to ‘remember’ and further understand this shift.

In kalchi kodi, stories and narratives emerge in Goa, from the fishing ecosystem of labour, indigenous communities of artisans, crafts-persons, technologists and oral history keepers, in an endeavour to understand this ‘fleshiness of the world’ within the paradigm of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Here, changes in technology (with regards to automation, virtualisation, platformisation, algorithms, machine learning and artificial intelligence) have an impact on the community, our culture and ethics, our livelihoods, the environ and climate change. We are and become what we consume (Sidney Mintz). The seas, oceans and ‘waters’ are the commons from where we emerge, grow and evolve.

kalchi kodi—a fish-curry and rice story is a proposed series of photographs as a narrative photodocumentary; audioscapes and stories as long-form interviews with an overlay as well as independent site-specific installation of aural soundscapes; essays; and an artist book. It is inspired by Allan Sekula’s Fish Story, a seminal early critique of global capitalism and a landmark body of work that challenged perceptions about documentary photography, investigating the maritime world as a site of class conflict and the ocean as a key space of globalisation. His work questions the idea of liminality and borders and he consistently shifts the relationships and meanings between a fixed land and a fluid sea. Sekula’s Fish Story manifests the ‘fleshiness of the world’ (Laleh Khalili) in constant flux as the sea disappears from the cognitive and imaginative horizon and is progressively rationalised by increasingly sophisticated industrial methods.

Rosalyn: Do you see yourself as a research-based art practitioner and do you make work in a studio?

Wency: I come from a film and lens-based practice and am habitually accustomed to working together with people and communities. The medium and form emerge from the proposed collaboration and narrative as a ‘subjectile’ (Jacques Derrida, Paule Thevenin). This strength of community memory and knowledge is a critical part of making any work. For me, art is invested in the making and dissemination of this knowledge.

I am from and currently live in Goa. Filmmaking comes from a discrete and industrial mode of production and, as a result of my apprentice training, I may initially work on paper/laptop for logistics. Working with people and technology is the primary part of my work and this is immersed in the material, ‘real’, tangible world outside walls. Here I am given access to community spaces to dialogue with and through the community. As part of process flow and working through post-production or editing, rehearsing or physically making the finalised work, I invariably use shared or industry studios, again collaborating with people. Today technology facilitates and encourages some of these processes to be digitised on my laptop, yet large portions of work are produced invariably in collaborative and shared spaces of making.

Rosalyn: How have some of your previous artworks or projects helped you define the nature of your artistic pursuits?

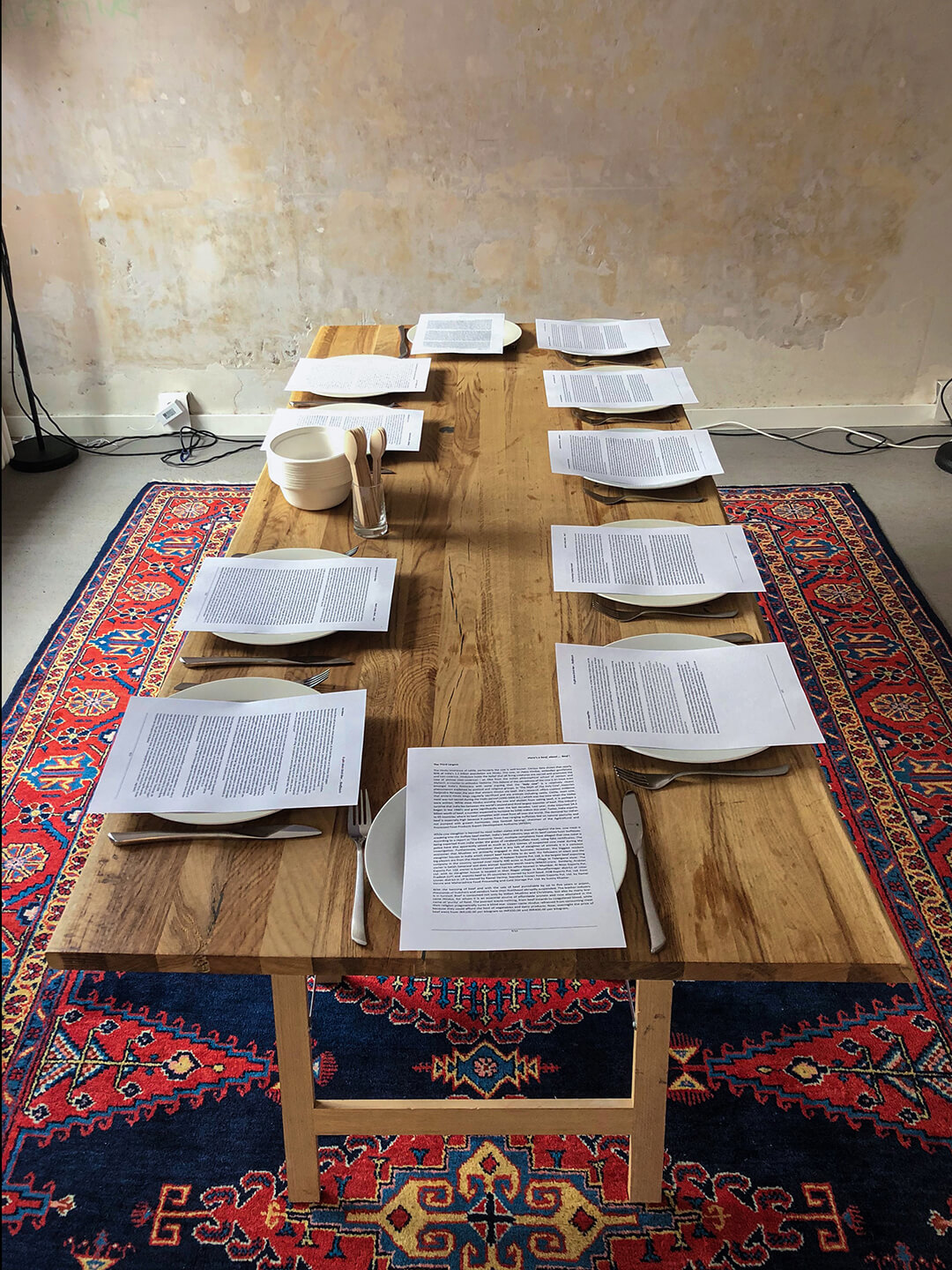

Wency: Seasoned (2014) [a multimedia and medium archive, performance and installation] allowed me to understand the ‘sensual’ and the ‘sensorial’. Food and recipes became for me a powerful medium. This work also unsettled within me this idea of an individual artist as an entire body of friends (classmates) who came together to work with me and present this showing. #unfair (2019) [a feature-length (52 minutes) documentary on skin, colour, race and caste] and mati (2020) [a 22-minute film exploring the complexity of flooding in Assam] emerged through the process of co-labour-abling. Here the making and dissemination of the work ran parallel to each other (not consequent), revealing the emergence of an inner resilience of a community. mati also brings to the fore the relationship of a community with land and water.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 11, 2026

The 82nd Whitney Biennial 2026 is a group show that reflects the ‘turbulent existential weather’ of the United States today.

by Srishti Ojha Mar 06, 2026

The British artist’s solo exhibition, ZOT at Varvara Roza Galleries in London, takes a postwar, postmodernist peek behind the curtain of artist studios.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Feb 27, 2026

Are You Human? brings together a staggering list of works that strive to question the consequences of our pervasive digitality but only engage with it superficially.

by De Beers Feb 27, 2026

The immersive installation by De Beers, featuring artist Lakshmi Madhavan, framed natural diamonds through art, nature and human expression at India Art Fair 2026.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Rosalyn D`Mello | Published on : Mar 27, 2024

What do you think?