A mute monolith of geometry and poiesis: Casa Luna by Pezo von Ellrichshausen

by Jincy IypeAug 10, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Vladimir BelogolovskyPublished on : Apr 29, 2024

The email I forwarded to Fred Noyes, the son of an American architect and industrial designer Eliot Noyes (1910–77) to discuss the house his father built for their family in New Canaan, Connecticut, was answered almost instantaneously, “We will have a party at the house this Friday. Why don’t you join us?”

Two days later after a one-and-a-half-hour drive from New York City, I was there. At first, I hardly noticed the house. Driving on a lonely winding road through a heavily wooded area I was taken by surprise when my car’s GPS abruptly announced the end of the journey. Looking in every direction I failed to recognise anything that would suggest my arrival. After a quick turnaround, I finally noticed a straight section of a stone wall, similar to the ones built by farmers around here since the early 1800s. The wall’s central opening with two barn-like wooden doors widely open, reassured me I was at the right place. Fred was right behind the doors attending to some last-minute preparations. His friends, enthusiasts of mid-century modern houses were trickling in. It is worth mentioning here that more than 100 modern houses were built in New Canaan from the late 1940s to mid-1970s by the likes of Philip Johnson, Marcel Breuer, Landis Gores, John Johansen, Edward Durell Stone, and even one by Frank Lloyd Wright. It was Fred’s father who chose New Canaan to raise his family and convinced some of his architect friends to follow him.

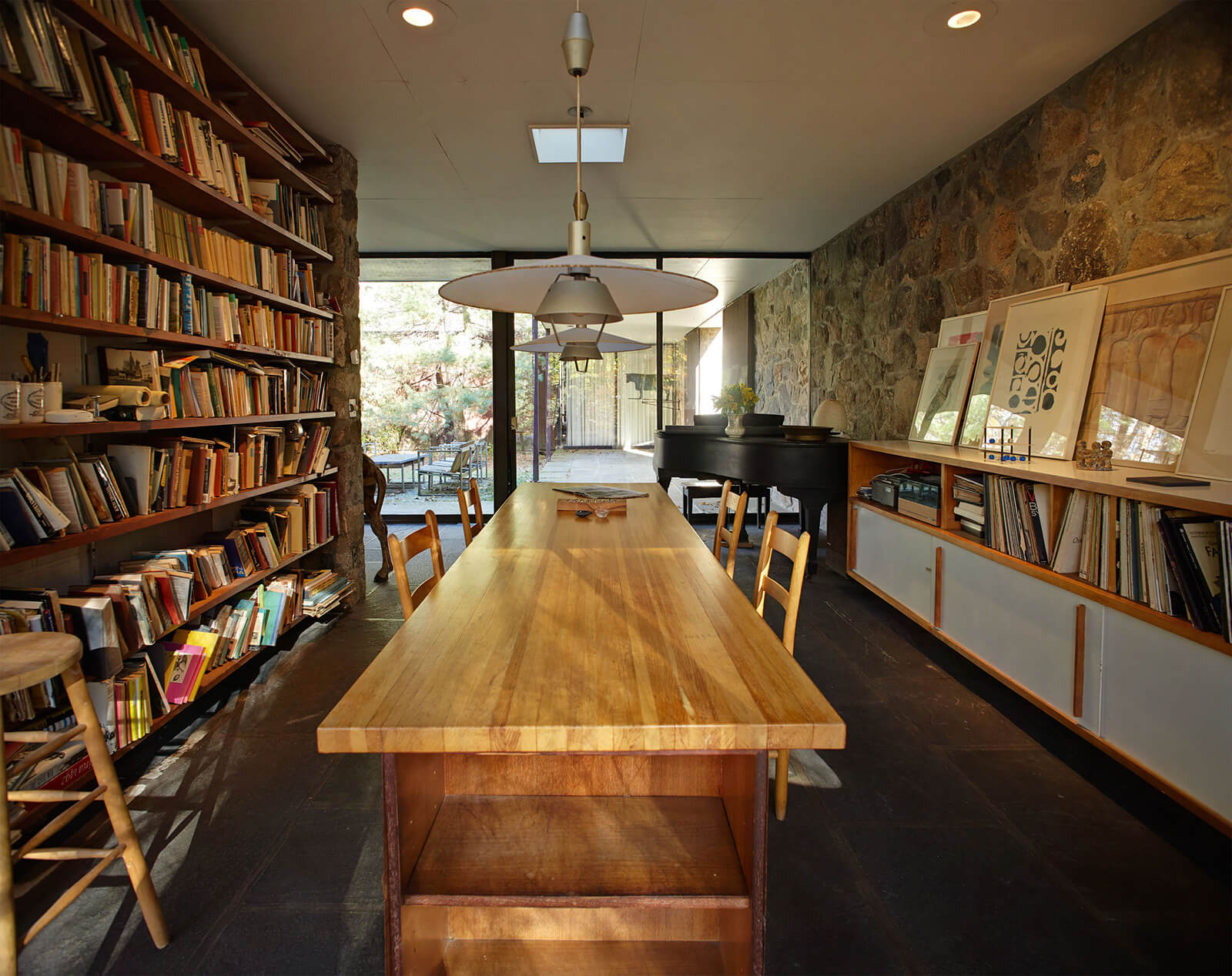

Once behind the wall, a stone-paved covered porch surrounds a square grass courtyard in the centre of the courtyard, all situated between the house’s two rectangular halves, largely see-through single-story orthogonal volumes. A study, kids' bedrooms, a master bedroom, and a pair of bathrooms are grouped inside the left wing, while a kitchen, dining area, great room, and library are arranged within the wing to the right; there are no doors inside this common space. The same stone wall as the one at the front completes the confines of the house in the back.

"The house is unlike a typical white shoebox modern house one might expect. My father turned the idea of a house being a bastion against nature on its ear by inviting nature to be part of the house. It belongs to the landscape, you cannot live here and not be a part of the land. Nature comes right through here,” explained my host.

I am given a quick tour. We start where Alexander Calder’s stabile, “Black Beast II” once anchored the courtyard.

“My father knew Calder well and he commissioned him to make this piece.” Fred continued, “Calder came to our house with a series of maquettes placing them near the piano in the living room. We then put a projector behind them and threw shadows across to the wall on the bedroom wing. We tried different options and the Black Beast seemed the clear winner. The date embossed on it is 1957.” Years later the piece was donated to the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, MoMA.

Fred was 13 when Calder made his sculpture; it was the first time he had done an outdoor stabile and became a precursor for his subsequent exterior stabiles. Fred joked that he and his siblings—two sisters and a brother—treated all art in the house informally. They even climbed on it, used it as a hiding place, and hung all kinds of things on it. It was a part of the family life, like everything else in the house. He added, “Informality is the essence of this house. First and foremost, the house was built for raising a family, not a showcase. Even though, on occasions, busloads of architectural students would show up announced, knocking on the door. Naturally, my mother would be furious, especially if we were sitting around in our pyjamas,” he laughed as we headed to the bedroom block. As we passed from the courtyard, I noticed the absence of thresholds at the doors while the same material—stone—is carried from outside in, which makes the idea of the continuum of nature even more accentuated.

“It is very observant for you to see that,” agrees the host and clarifies, “the inside and outside floors are made at the same level, so there is a sense of one plane going through both the interior and exterior. It’s part of the expression that the inside and outside are integral.”

Eliot Noyes was born in Boston and grew up in Cambridge before going to Harvard in the 1930s. He worked in New York at MoMA where he was the first Director of the Industrial Design Department from 1940 to 1946, a position he received at the recommendation of Walter Gropius, his architecture professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. By the mid-1940s he decided to go to the suburbs to raise his family away from New York City. He then became the design director for IBM for over two decades and a member of Harvard Five, a loose group of like-minded progressive architects practising in New Canaan; the other four comprised Johnson, Breuer, Gores and Johansen.

Speaking of that experimental time, Fred casually dropped a beautiful phrase, “New Cannan became the Florence of Modern architecture.” He elaborated, “My father was the first who came here, and then the others came because it was close to New York. Properties were cheap, taxes were low, and building codes were not restrictive. It was a nice community to live in. He talked about it with his friends, and they all came one-by-one. Then they took independent directions and made their lustrous individual careers. They were young and competitive and it became this incredible hotbed of exploration. Of course, who will compare these guys to Leonardo and Michelangelo? But it is also true that they extended their architectural ideas in ways that were picked up across the country and into the world. Many houses here in New Canaan exemplify that early thinking.”

We enter the guest wing just in time for the party to start. The house is alive, loud, and festive at this dusk hour. Looking around, four merry-go-round animals catch my attention. They came from different carousels. Fred pointed to some other artefacts, “My parents would always buy what they liked. That would be true of all their art. They would go to New York galleries on their anniversaries and look for something they could afford, often picking small maquettes to be placed on a large coffee table in the living room. Once full we would find other places in the house to put art in.”

There are small pieces here by Calder, Miro, Giacometti, Arp, and others. Fred’s parents bought all these pieces when these artists were not yet famous. There was a mix of styles and eras in these acquisitions. Fred added, “It was quite enriching for us kids. We had no idea that one day these pieces would become valuable. Dad was also an artist and wanted to become one. He even studied art in the summers before college but didn’t think he could compete, so he decided to become an architect. Still, he never stopped doing watercolours. He was good at rendering.”

After the party, Fred responded to several more of my questions.

Vladimir Belogolovsky (VB): What are some of your earliest memories of this house?

Fred Noyes (FN): I remember the day we moved into the house; it was 1956 and I was 12. It was very dramatic. Before that, we lived in another house down the road, the first house my father built in 1947, Noyes House I, which I also remember quite well. I was three then. These two houses were just half a mile away from each other and I used to walk between them as a child. It was such a dramatic land with heavy woods and the Five Mile River going through it. I was very much into birds and animals that lived all around. I remember taking part in cutting down the trees for our second house, which initially was going to be further up the site. But he moved it down into the pine grove closer to the river, for which we had to cut 60 trees. It was painful but that is what ultimately made the house feel belonging to the land.

The first night we moved in I remember the visual drama from the lights on the roof shining off into the landscape toward the river. Also, the smell of linseed oil and turpentine used to seal the floors; that smell is ingrained in my memory. It is such a positive smell because I associate it with the house.

VB: What was the reason for moving from the first house after just a few years?

FN: My father advanced his understanding of architecture since then and that was the main reason for building a new place for our family. He had fresh ideas. He was always inventing things and what he could do for himself that he could not necessarily do for a client. Just think about it, designing a house where a client would have to go outside to get from one room to another would be unthinkable. Working on his own house gave him that freedom. By the way, there is no bathroom on this side; when you need one you have to go through the courtyard there. [Laughs.] It was the relationship between the inside and outside that he experimented with in all of his houses. First, he would break the box and then integrate it with the landscape around it. He wanted to use natural materials such as stone to integrate them into the site to the point that you could hardly see the house from the road.

VB: Now I see that hiding the house was intentional. What was it like to grow up here?

FN: To be in the house continued to be dramatic. The living room opens like a big screen porch; all the sliding panels open and in the summer the inside and outside essentially become undivided. We would always be outside. Then the house would become a part of nature. Another aspect is the simplicity of the design. There is a chimney, a few stone walls, and a bunch of sliding glass panels. That gives you the ubiquitous ability to do things with the interior which you can’t do when you have traditionally defined rooms. With the visual extension to the outside, the interior space feels so large that the furniture inside has to have a substantial weight to hold it.

Then there is art. It was always changing. Paintings and small sculptures were typically bought to commemorate my parents’ anniversaries. There was a continuous change of flavour of what it was like to be there. Art and all kinds of things on display were not something we revered as if we were living in a museum. It was a part of living. And it encouraged us to draw, paint, make things and move them around. My father would bring some sticks and say, ‘Let’s see what we could make with them!’ Or he would involve us in making funny Halloween costumes. Everything was about play. We could have a Picasso and right in front of it we could have a painting my father did or a piece of sculpture my brother did; these pieces would be shuffled around. It was a natural setting for the constantly changing lifestyle. Art was not precious and anyone could do it, whether you think you have a talent for it or not. It was a way of life to do what feels good.

VB: I understand that apart from Calder the house was frequented by Charles and Ray Eames, Isamu Noguchi, Philip Johnson, and Marcel Breuer, right?

FN: You have to remember that none of these people were famous then. The term “Harvard Five,” my father’s architectural contemporaries in New Canaan, was coined many years later. At the time there was no sense of being a part of an isolated group. Yes, they knew each other and shared a similar spirit but they were just friends trading ideas. There was a sense of community and they often came for dinner and parties. Some would stay overnight. I remember Charles Eames drawing a heart on the blackboard in one of the bedrooms. It was his way of saying thank you. Two days later it was gone. [Laughs.] People would come to see the latest films projected on the mantel over the fireplace and so on. Their relationships were also informal. My father arranged for Calder and Noguchi to do some artwork for the IBM Building. Calder also made his mobile for the house and then my father bought another one. So, we had three major pieces by Calder; two were specifically made for the house. So, all of these people came often. I was just a kid and didn’t know who was who. The sense that they were giants of their era grew slowly.

On my way back to New York I was thinking about the future of the Noyes House II. Surely it ought to be preserved. People would love to visit it. In 2019 Fred placed covenants on the house. Now it cannot be knocked down. Nothing can be added to it. It cannot be painted and its courtyard can’t be filled. The house may become a museum or, as Fred suggested, “It may continue its life as home if a sympathetic owner comes along and decides to raise a family here.”

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Vladimir Belogolovsky | Published on : Apr 29, 2024

What do you think?