Aagaram Architects' design for SITH Villa counters Vellore’s tropical climate

by Almas SadiqueJan 04, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Almas SadiquePublished on : Mar 11, 2025

Al Borde, an architectural practice based in Quito, Ecuador, is a partnership firm that divulges its distinctive mark via projects designed in collaboration with local communities and in continuation of previously initiated ventures. Even as the practice bases its ethos on the value of questioning and adapting in accordance with local traditions, resources, materialities and skills, Al Borde seldom plants itself within contexts to fulfil imagined necessities or conceited visions. The Ecuadorian architecture practice, with David Barragán, Pascual Gangotena, Maríaluisa Borja and Esteban Benavides heading the collective, append and customise their services and expertise in tandem with the projects being approached instead of tailoring the design of buildings in concert with a monostyle or monoprocess.

Beyond its participation at the Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2023, Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism in 2021 and Venice Architecture Biennale in 2016, Al Borde has won awards such as the Holcim Award Acknowledgement Latin America in 2014, the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture in Paris in 2013 and the Schelling Architecture Prize in Germany in 2012. Most recently, the practice was awarded the BancaStato Swiss Architectural Award 2024 for its ethical, aesthetic and ecological contribution to contemporary architectural culture.

No plans, no goals. There wasn't an idea to run a studio, actually. We did not begin like a corporate practice with a mission, vision, goals and stuff like that. – David Barragán (when asked about initial plans and goals for Al Borde)

To gain a better understanding of the inherent workings of Al Borde, based in South America, we established a dialogue with David Barragán, one of the four founders of the studio. Barragán, who cites his inspiration in the likes of Paraguay-based architect Solano Benitez, Mexican architect Mauricio Rocha and Mexico-based Colectivo C733, illustrates anecdotal retellings about the studio’s formation and evolution over the years. Edited excerpts from the conversation are as follows.

Almas Sadique: What led to naming the studio Al Borde?

David Barragán: Al Borde in Spanish means something like ‘on the edge’. For us, since the beginning, it has been important to move out of our comfort zone, to try to find new scopes, to practice, develop our lives and push our limits to discover new kinds of options. And, we thought, if we are on the edge, if our practice is always on the edge, if our state of mood is on the edge, we are always going to be alert to find new paths, to find new options, to discover different kinds of scenarios. We also wanted to avoid using our last names as the name of the studio since it is too corporate.

Almas: How did the four of you meet? Tell us a little about your backgrounds. What eventually led to the founding of Al Borde?

David: All four of us are architects. We were born and raised in Quito in Ecuador. We graduated from the Faculty of Architecture, Design and Arts of the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador.

First, I met with Pascual Gangotena. We are the oldest and we have been friends since the first day of school in 1999. After we graduated, there was a big economic crisis in Ecuador. There weren’t many opportunities and we were working part-time jobs in different areas. Pascual was in the housing sector, working for vulnerable people. I was working with Jose María Sáez.

One day, Pascual and I met at a friend's gathering, and he told me that a close friend asked him to design a house. He didn't have enough time to develop it himself because he didn't want to quit his part-time job. So, he proposed to me that we do it together. After that, we could keep trying to find new options and possibilities. This was the beginning, and after 18 years, we're still together. It’s because, after that project, we discovered that we had a good partnership and common interests, more than being good friends. So, little by little, we built our practice. In the beginning, we didn't have a name, either. We decided on the name much later, and our studio began in 2007.

During this time, we also began to consolidate our practice and hire some people. Many people have been working with us, among whom were Esteban Benavides and Maríaluisa Borja. Since their work aligned with the studio, we invited them to be part of the partnership and transform our studio from two partners to four partners.

In the beginning, our Indigenous understanding was very naive because our education was very Eurocentric. – David Barragán

Almas: An excerpt from the website reads, “The design centres the discussion on the sustainability of life (resources, co-responsibility, consumption, gender and social inequality)”. Could you expand on how these five aspects are addressed at Al Borde? Please tell us about some projects where these aspects have been addressed to culmination.

David: When you talk about sustainability, it's not only about the environment. Our understanding of the sustainability of life is more holistic and oriented towards understanding the many impacts our projects can create.

So, talking about resources, for example, we developed a house in Chile. When we began to study the context, we discovered a quarry near the construction site. So, even before we knew how we would design the house or how many people would live there, we knew about the quarry and that the house would be built using the quarried stone. That was our approach to creating a connection with the site and the people. It's also about how to create a redistribution of the wealth of the project on the local site in the local community. We need to understand the project from different kinds of scope, more political and more territorial, more cultural. Let us understand this kind of co-responsibility with the site because when you are building a project, you have a lot of this kind of responsibility. It’s not like a spaceship that lands on a different site.

Similarly, with another social project, the Yuyarina Pacha Community Library, we applied for its founding together and designed and built the structure with the local community. This helped transfer new skills within the community and disseminate local knowledge about the site, materials and construction techniques to us. We are aware that each project has the opportunity to create this kind of co-responsibility. Also, when we talk about consumption, it’s easy to buy all the construction materials from any monopolised seller. But for us, it's very important, again, to build with local materials because it lets us understand in a better way the cycle of the materials.

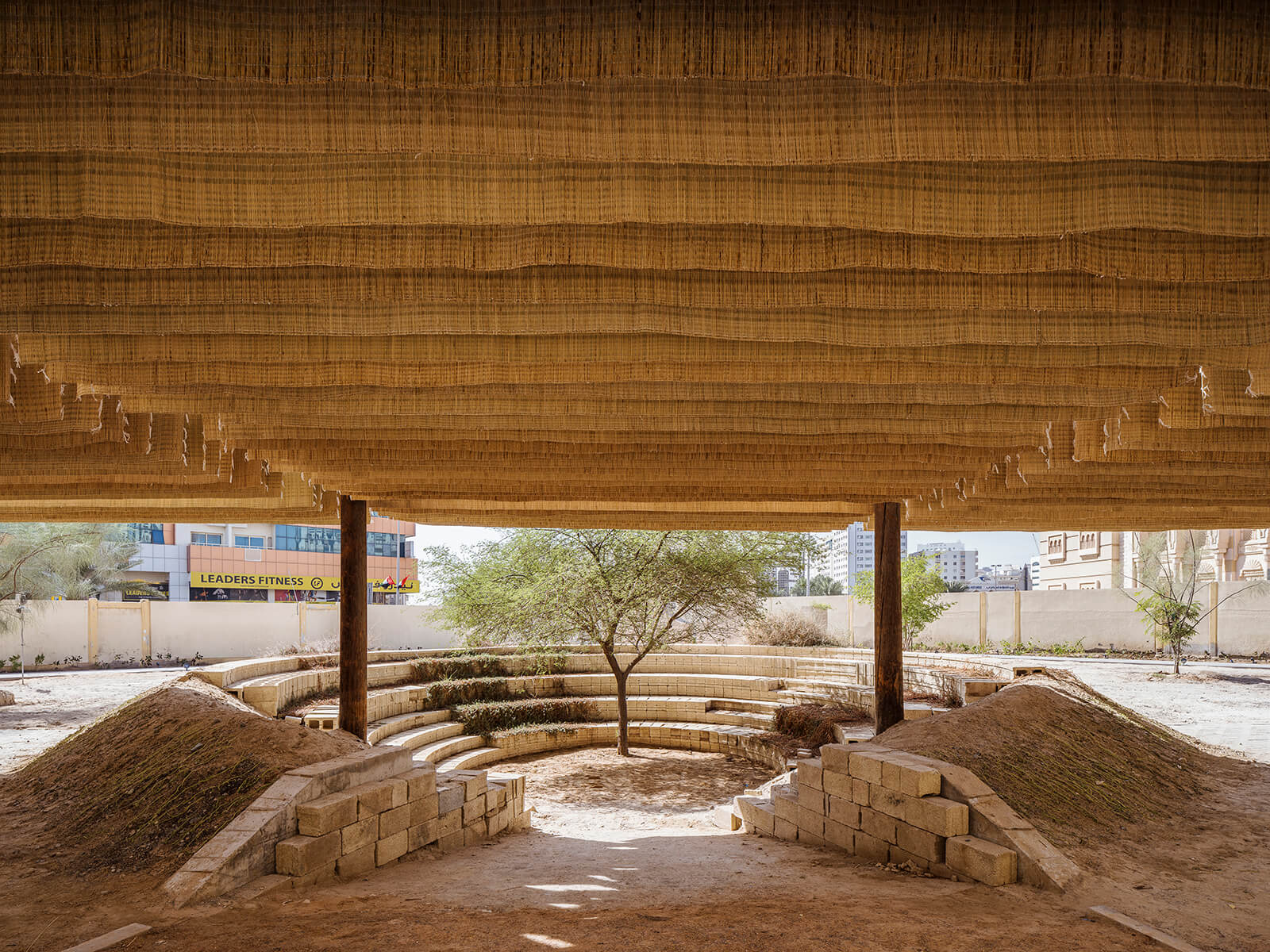

Also, for our Sharjah Architecture Triennial pavilion Raw Threshold, it was difficult for us to find something local in the UAE because the settlements are cities built in the middle of the desert with few resources. But, suddenly, we discovered that the Sharjah Electricity, Water, and Gas Authority was replacing the wood poles with steel ones to transform the electricity network of the city. They had a bunch of these big poles in storage. It was important for us to understand the source of the material to ensure ethical consumption. For the temporary pavilion we were building in Sharjah, it was more important than ever to understand the cycle of material. All of the materials needed to come back to storage to not create any kind of trash. Further, we are working a lot with vulnerable communities to try and tackle social inequality.

This also involves us applying for different kinds of funding to develop different kinds of educational, cultural and productive facilities, usually in the outskirts and in the countryside, to drive meaningful change in areas overlooked by the government. To ensure sustainability with respect to gender, we are trying to involve women in the construction labour. It's not easy because our society is completely patriarchal. We also try to address the gendered perspective when we work with communities promoting the rights of sex workers and trans-women in the city.

So we're always working with so many different groups trying to understand architecture as a big point of view, not only from the architecture itself, more than a tool, more than a tool to transform your life, to create an impact in your life.

For us, it is very important to understand our context and not to find any kind of validation in the Global North. That’s why we began to find the answers to our questions in the local materials, local people and local knowledge. – David Barragán

Almas: Has Al Borde utilised or reinterpreted certain Indigenous architectural practices for some of their projects? If yes, what are some examples?

David: There are a lot of Indigenous construction techniques that we have utilised, but I think one of the most magical for us was when we discovered that we could build with living trees. We utilised this building technique for our project, Garden House. The project is based on a tradition of living fences in the countryside since the beginning of time. There was a tradition in the Andes, in the highlands, that you needed a fence to protect your animals. And they used to cut the El Lechero tree and immediately replant it. After a few days, the tree develops roots. This is how they easily build these living fences by replanting trees in the desired pattern and connecting them with a metallic wire. When you cut trees using this technique, they also don’t grow any more, making the fence very stable.

For the Garden House, we made columns for the building using this indigenous technology. Imagine how beautiful it can be to build columns with living trees and also try to organise a geometric pattern with living trees! Also, our client for this residence was an ecologist who had moved out of the city to this plot on the outskirts. He always said that he wanted to feel nature and stay in touch with nature. So, we asked him, “What if your house is built with living trees?” When we presented this technology to him, he asked, “How many projects have you built with this technology?” We said, “None. That's why I must explain this to you because it is a risk to move from fences to architecture.” He liked the idea and wanted us to find a possibility to build it. So, we found more information, experimented and built the structure. So, this is very specific to the site, but we have also developed different projects using rammed earth, adobe and other local materials.

Almas: Since Al Borde utilises design as a tool for social awareness, what would you say are some ways of ensuring that the messaging is not lost in translation or does not become diluted for the general public? Additionally, how can community architecture be framed to attract the interest, attention and involvement of the general public?

David: I think everything is about the participation process. We don't invent any kind of necessity. We don't have this kind of approach like NGOs in the Global North, who visit sites in the Global South and tell the locals that they need a school for education because education is going to change their conditions. No, it's not like this. We work only on ongoing projects. So, if you’re running a cooperative of people who are involved in developing any kind of food or are working with sewing or pottery or even developing a school, we understand that you are organised, you're running a project, and we know that architecture can help create a better space to do your work, to create this transformation that you are doing on-site. We get involved in only these kinds of projects, not trying to embed any kind of necessity, only where the necessity is clear because there is an ongoing project. In such projects, we can work together to find how architecture can improve lives, better accommodate activities or improve the intended action. And then, we always work with participative design. People are involved in the decisions and you have different points of view.

On the other hand, governments always try to show you an idea and ask the community whether they need it or not. They call this participation. But for us, it's not about this, not about questioning if you want a project or not. It’s about conceptualising the initial ideas together and involving the community in the design and building process. We bring models to the communities to discuss in a better way because we are aware that it's not easy to read plans. This also allows them to get involved in the procedures of building, suggest local materials, etc. So, we are completely open to involving as many people as possible. We also keep the construction skills of the community in mind while designing. Since the community is involved in the project from the beginning, they also know how to maintain them afterwards. So, that’s the way we involve people in our projects.

Almas: Has Al Borde ever undertaken any self-initiated projects? Please tell us about them.

David: Our self-initiated projects happen when they pivot between communities, any kind of funding and maybe researchers. For example, the school and the library in the Amazon happened because one very close friend, Ana Maria Duran, had her research based at Yale University in the US. She studied the Amazon jungle, and one day, she sent us an email: “Guys, I just met an amazing community that has a book club. They are very engaged with this book club because the education in the Amazon is bad. This book club is transforming the education of these kids. I think you can find ways to build a library for them because they need this educational space”. And we said, of course, yeah, we want to meet them. We studied the whole project and applied for funding. Once we received funding, we began the design and the construction. So, it's not about inventing any kind of project. It's more about how we connect with these kinds of institutions.

Almas: Al Borde also delves into modes of knowledge production with films and essays. Who is your target audience for this kind of knowledge dissemination?

David: I think the target audience for this narrative is young students and the young architects. There are a lot of young architects who want to work—transforming and creating impact in their societies—and they don't know how to deal with these kinds of projects. So, they are the target audience. Yeah. All of these restless people.

Almas: What advice would you give to young architects today?

David: Be very curious because you can find solutions everywhere. Interact with people because that leads you to connect with so much knowledge. Try to move ahead from traditional architectural knowledge and find your answers via different sources. I think when you open your mind to the local sources, when you begin to understand that there are so many resources, so many points of view and ways to learn, it's going to be better for you as a young architect. You are going to discover your own language based on your local conditions.

Almas: Tell us about some challenges you faced while practising architecture in Ecuador over the years. How did you deal with them?

David: Keeping us alive! Keeping our studio financially sustainable. This has always been extremely challenging while undertaking what we consider ethical work. In the beginning, we tried combining different kinds of activities, teaching and building private projects like single-family houses. Then, little by little, we began to understand that in order to make it sustainable and always be involved in social projects, we need to understand where the money comes from. We began to learn how to write economic proposals, how to find funding, how to avail open calls for funding, etc.

Almas: What are some of the most memorable projects that the studio has worked on? Additionally, tell us about some heartening reactions that you may have received from clients and stakeholders.

David: I think the living trees project, because nobody understands how it was built. Also, when we developed our project in the UAE, the Raw Threshold pavilion, it was built as a pavilion in a territory where there is a perception of abundance because they have access to everything and they have money for everything. So, they’ve lost their identity in the architecture, in the space, in the construction of their cities, and are trying to be more than a global city with a lack of identity, very generic. When people visited the pavilion, there was a good reaction because they immediately connected with the site and with the Arab world. But at the same time, a lot of people connected with their own site, because when you see raw materials, it helps establish a kind of relationship. So, for us, the reactions that we received with the pavilion were really, really good.

Also, we like to see kids' reactions to our projects because kids perceive the space in a completely different way. It's amazing how they discovered so many different places to read, to see, to engage with our library design project. This kind of reaction is very inspiring. It also inspires us to build spaces that can be used for multiple purposes; the library is now used for fancy dinners at night, workshops in the morning and community gatherings with different kinds of layouts and experiences.

Almas: What’s NEXT for Al Borde?

David: What's next! After 18 years of working together and always trying to avoid the responsibility of thinking about what's next for us, I now want to say that staying together another 18 years will be great and open our scope of work further. Also, if we can work on more projects related to social impact, build more public space and more educational space, and work on projects that can transform the daily life of communities, I'll be more than happy.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Almas Sadique | Published on : Mar 11, 2025

What do you think?