Fragmented histories: Reliving The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower at MoMA

by Jerry ElengicalOct 08, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Zohra KhanPublished on : Sep 19, 2025

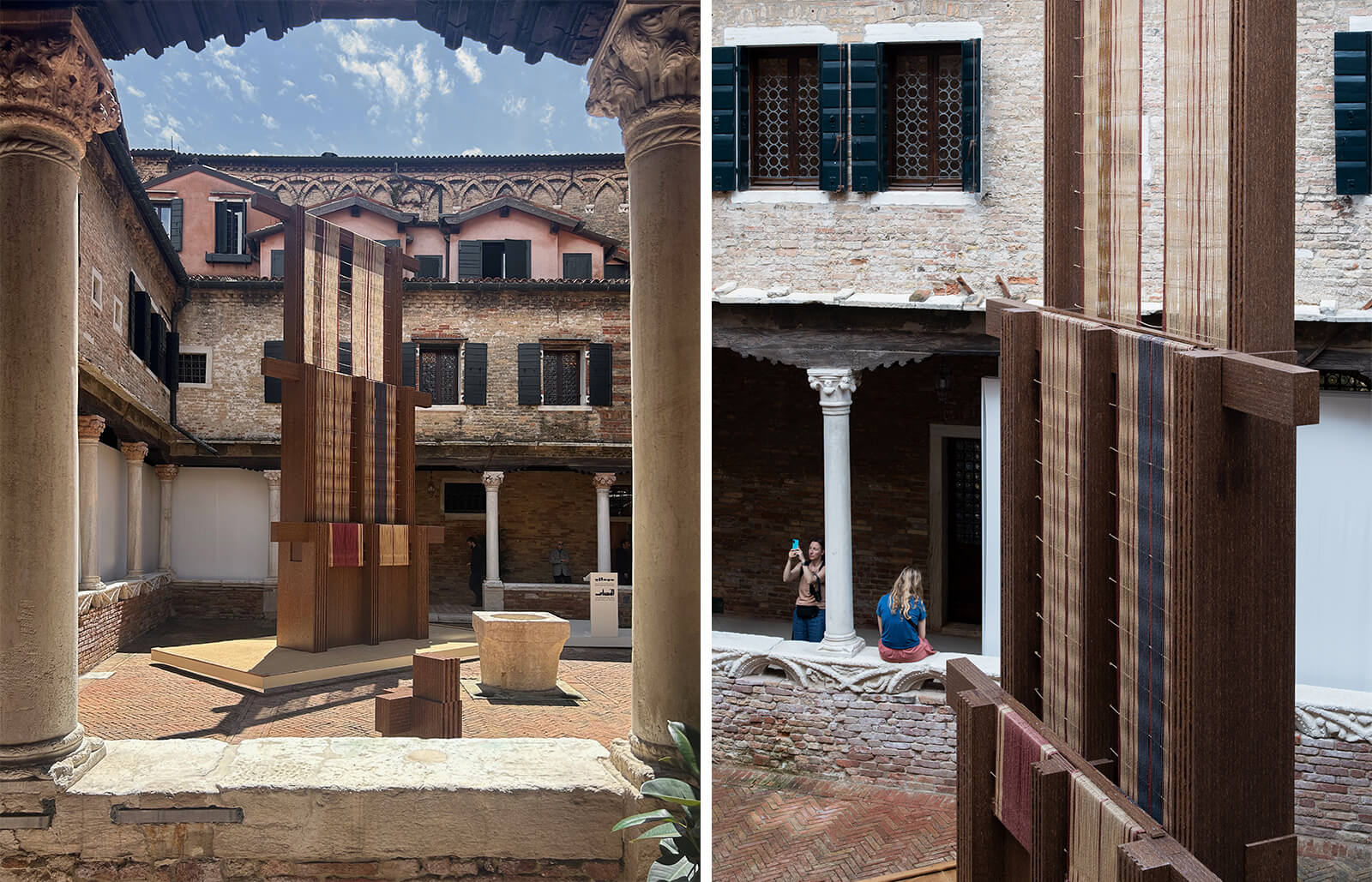

Beirut-based EAST Architecture Studio operates under the banner of preservation as practice. Led by architects Charles Kettaneh and Nicolas Fayad, the studio brings forth a sensitively layered approach to architecture—guided with incremental gestures—in tying the historic with the contemporary. Themes such as conservation, decay, restraint and repair populate their experimental repertoire, which responds to the precariousness of Lebanon as a nation. The studio works across housing, cultural buildings, exhibitions, master planning and research with the idea of creating spaces for inhabitation and also as evolving conversations between art, craft and place. “We see value in working with what already exists, no matter how fragile, and in allowing small, precise acts of design to accumulate into meaningful change,” Kenneth and Fayad told STIR in a recent interview. From reviving a ‘60s modernist edifice by Oscar Niemeyer that won them the 2022 Aga Khan Award for Architecture to winning the Diriyah Biennale Foundation’s inaugural AlMusalla Prize with their loom-like vision of a modular musalla (prayer space), the studio’s work is aspirational yet unfettered by trends and typologies.

Speaking with STIR, the architect duo discusses their journey so far. Following are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Zohra Khan: Is there a definitive moment that inspired the inception of EAST Architecture Studio?

Charles Kettaneh, Nicolas Fayad: The origins of EAST Architecture Studio lie in a shared vision of a research-based, experimental architectural practice grounded in local cultural, historical and material awareness. An early catalyst may well have been our encounters with the Rachid Karami International Fair in Tripoli, an abandoned site designed by Oscar Niemeyer in the early ‘60s, that we visited as architecture students, whose dilapidation and potential have deeply resonated with us. Fifteen years later, we were invited to reimagine the future of one of the pavilions of the fair. That return marked the beginning of a broader journey that has reaffirmed our belief in architecture’s power to repair, reinterpret and re-engage with history.

Zohra: What were your student days like at the American University of Beirut? What were some of your individual formative fascinations (and pet peeves), as well as things you both resonated with equal intrigue or annoyance?

Charles, Nicolas: Our years at the American University of Beirut were full of excitement, fuelled by a politically charged academic culture, intellectual pluralism and openness to history and modernity in architecture. Critical thinking was key in shaping our understanding of what architecture could be, beyond form and function, and in understanding architecture as a medium that can negotiate between conflicting realities. That spirit of inquiry continues to guide our work today, as we search for ways to build that are both contextually ingrained and imaginatively expansive.

Zohra: How would you define the current landscape of architectural practice in Beirut, and how do you navigate its precariousness and eccentricities?

Charles, Nicolas: Beirut’s urban character has been shaped through layers of erasure and trauma, such as transformations under French colonial planning and post-war downtown reconstruction, which have led to disconnected public life and neglected cultural heritage. Our practice responds to this precariousness through context-sensitive, incremental interventions rather than grand erasures or masterplans, which have always proven to fail within Lebanon’s fragmented social and political climate. We see value in working with what already exists, no matter how fragile, and in allowing small, precise acts of design to accumulate into meaningful change. This enables us to navigate uncertainty with resilience, while envisioning forms of urban life that are more inclusive, adaptive and enduring.

Preservation becomes less about freezing a certain moment in time and more about enabling continuity. – Charles Kettaneh, Nicolas Fayad

Zohra: You operate your studio based on the core tenet of preservation as a way of practising architecture. How does your studio perceive decay and the idea of ‘bracing’ something?

Charles, Nicolas: In the renovation of Niemeyer’s Guest House, for example, preservation as practice could be shown through interventions like a glass partition that almost appears to never fully touch, neither the ceiling nor the floor, or where new additions can be dismantled, leaving no trace on the original structure. On such sites, decay acts as a canvas for revealing layers and narratives; here, ‘bracing’ might be understood as careful support of what remains, allowing for adaptation without cancelling history. Preservation becomes less about freezing a certain moment in time and more about enabling continuity. Each act of repair or bracing opens up the possibility for new life within the old, allowing architecture to remain in dialogue with both memory and change.

Zohra: Some of your most distinguished projects reveal radical interventions upon ruins or empty landscapes, in which the proposed architectures seemingly balance a silent timelessness while being reversible in nature. Why are these contradictions important for you?

Charles, Nicolas: These contradictions are important because they honour the original while still enabling new life. By accepting these dualities, we strive to create architectures that are robust enough to endure uncertainty while remaining open to future reinterpretations. In doing so, each project becomes less a fixed object and more an evolving framework for inhabitation. The Guest House renovation, for example, is both structurally honest and introverted yet light, adaptive and serene.

Zohra: You avidly collaborate with artists and regard their interventions as key to the architectural narrative of your designs, something one sees in the installation On Weaving and the Capsule Retreat. What layers do these collaborations add to your vision?

Charles, Nicolas: Many of our projects suggest an interpretive, tactile engagement with artisanal techniques and spiritual atmospheres, a metaphor for how collaborations with artists enrich architectural narratives through symbolic and material layers. In projects like the Capsule Retreat, a living gallery for an art collector includes site-specific installations by Middle Eastern artists, emphasising architectural spaces as platforms for artistic narratives. Such collaborations expand the agency of architecture beyond the built form, transforming it into a shared cultural experience. They allow our projects to resonate not only as spaces to inhabit, but also as evolving conversations between art, craft and place.

Zohra: Your built forms create a presence for them, yet in the way they are conceived, they avoid coming across as spectacles, rather something that is almost imperceptible. There is a sense of restraint in the visual experience. Would you like to comment on this?

Charles, Nicolas: We are indeed interested in architectures that instigate curiosity. In some cases, this is translated into forms that are understated externally yet radiant inside, a spatial quality that avoids spectacle and instead invites subtle discovery. We like to think of this as a quiet meditation, visible through sensitivity to light, material, proportion and structure; almost like an aesthetic discipline.

Zohra: How would you define the transforming landscape of modernism in the Global South, particularly referencing your contribution to the Niemeyer Fair in Tripoli?

Charles, Nicolas: The Niemeyer Guest House project is a vivid example of reinterpreted modernism, not through erasure but through incremental, pragmatic restoration efforts that serve the local cultural economy. Through similar conservation projects, we try to illustrate architecture’s capacity for repair in crisis as a means of incremental urban regeneration.

Zohra: What do you find the most liberating aspect of your practice? And the most challenging?

Charles, Nicolas: Liberating: The drive to hold on to entrepreneurship and rootedness, creating socially meaningful architecture amid adversity and choosing to operate in a region rich in history by conviction rather than convenience.

Challenging: Seeing that culture is often overlooked, meaning that real transformation must often begin with planting a small seed, which can take a very long time to grow.

Zohra: What is NEXT for you?

Charles, Nicolas: What lies ahead for us is less about predetermined projects and more about continuing to explore the questions that have guided our practice from the start. We are deeply interested in the ways programs, be they cultural, residential or civic, can generate new forms of collective experience when they are rooted in history yet open to reinvention. Through our interventions, we have learned that even the most fragile or overlooked sites hold within them the possibility of renewal, and that architecture’s role is to reveal and adapt. This ongoing engagement with preservation, decay and restraint has shown us that architecture can be both modest in gesture and radical in impact. These themes remain compelling to us because they affirm our belief that architecture is ultimately about continuity; about building bridges between past and future, memory and possibility.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Zohra Khan | Published on : Sep 19, 2025

What do you think?