Yuri Suzuki's sound installations combine human, environmental and sonic values

by Dilpreet BhullarMay 03, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Aarthi MohanPublished on : Oct 07, 2025

At first glance, playgrounds may seem like modest fixtures of suburban life—scattered slides and swings that form the backdrop to fleeting moments of childhood. Yet they carry stories that reach far beyond recreation, shaping communities, memories and even the ways cities are imagined. It is this layered view of play that drives The Playground Project, currently on display at the Melbourne’s Incinerator Gallery until October 12, 2025—an exhibition that treats playgrounds not as incidental furniture but as cultural landmarks.

The Australian debut of the travelling exhibition The Playground Project—conceived by Swiss urban designer and political scientist Gabriela Burkhalter—arrives with an international pedigree, having been staged in Europe and the United States at institutions such as Kunsthalle Zürich, the German Museum of Architecture in Frankfurt and the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh. In Melbourne, however, it has taken on a character of its own, shaped by the suburb it is set in and the collaborations with local artists, architects and designers who have reimagined the project for an Australian context. The Incinerator Gallery itself, designed in the 1930s by American architects Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin who are best known for their visionary design of the Australian capital of Canberra, becomes both a backdrop and a participant in this playful takeover, its history and architecture woven into the creative offerings dotting the gallery spaces.

For Burkhalter, who has spent years researching the theory and practice of playground design, the idea of treating play seriously is not a provocation but a necessity. “We are beginning to understand the sadness and ugliness of some of the public spaces in our cities,” she told STIR. “These spaces are designed for circulation, shopping and parking. They prevent children from playing football or chasing each other wherever they want. We realise that everything is linear and rational and that non-functional design is avoided. However, play can offer a refreshing perspective on urban planning—there is a lot of potential!”

Burkhalter’s conviction is that playgrounds are not self-contained islands but indicators of community health, because children are tethered to their immediate environments. Unlike adults, who can roam widely in search of leisure, children depend on the spaces closest to them, shaping and being shaped by those spaces. That dependency came into sharper focus during the pandemic, a period Burkhalter often references when describing how quickly neighbourhoods reveal their strengths and shortcomings once mobility is curtailed.

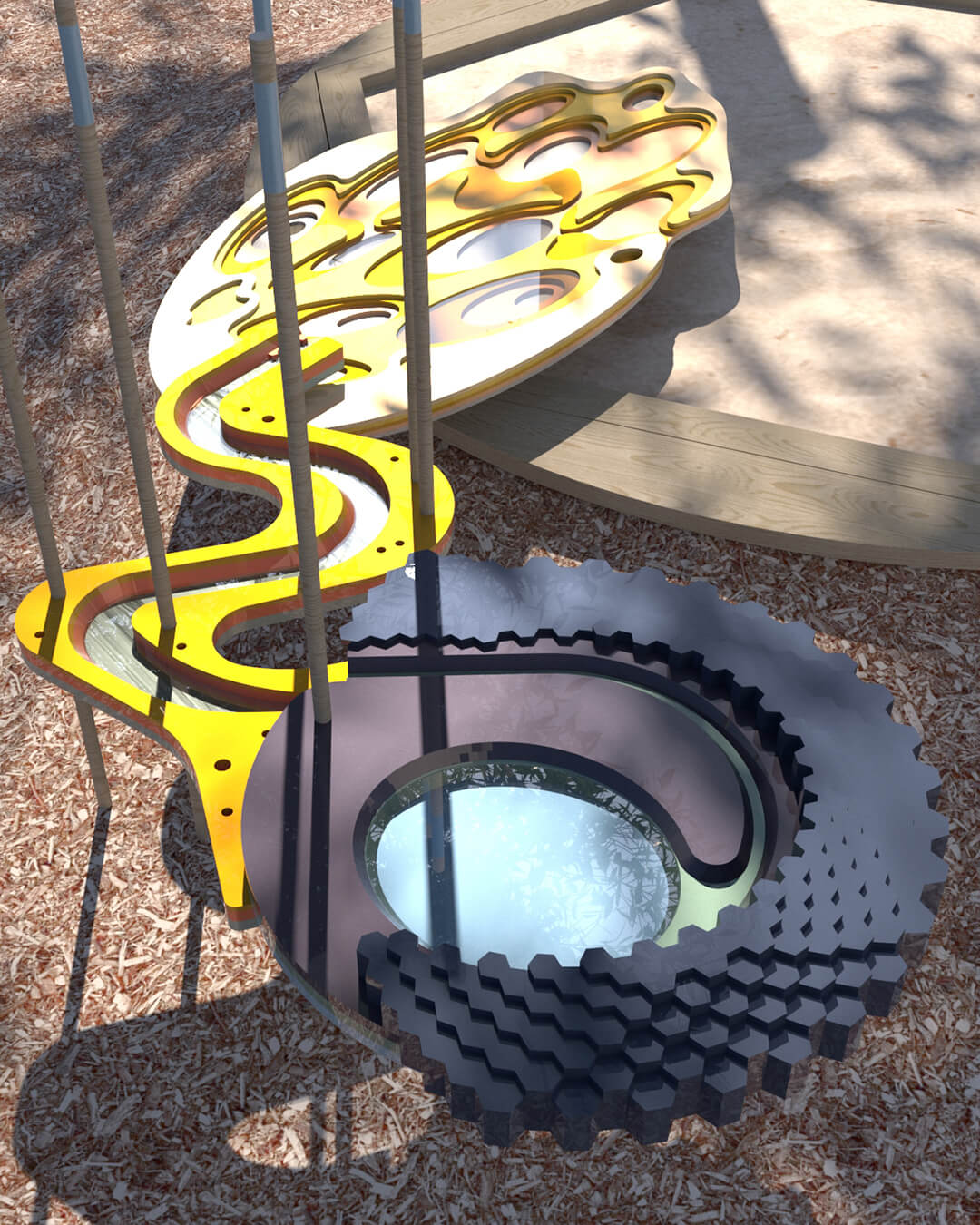

That sense of embeddedness is reflected in the exhibition’s Melbourne-specific commissions. BoardGrove Architects, the local firm appointed to design the exhibition, has also contributed their own project, The Ringtales Playground, which builds on the idea of nature play while drawing links to the Griffins’ legacy; an approach that married geometric design with civic purpose.

Mary Featherston, a pioneering designer in early childhood education, has joined forces with artist Emily Floyd to present a new iteration of their collaborative project Round Table. Installed in the gallery courtyard, it serves both as a gathering space and a play sculpture, with a modular design that recalls the 1977 publication Ripple—for which Featherston designed the cover and Floyd’s mother, Frances, served as editor. Ripple was grounded in the idea that playgrounds should be part of a broader network of resources for families and communities. A selection of the prints inspired by Ripple is also on display, reinforcing the connections between art, activism and childcare.

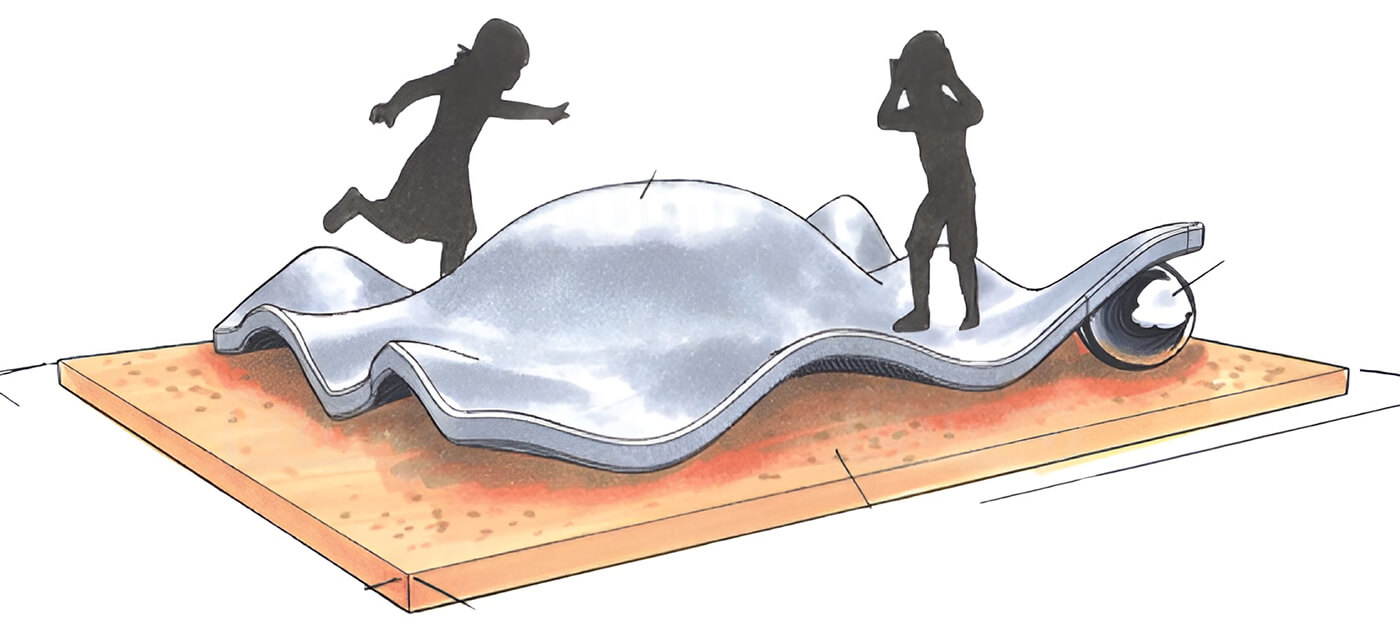

Another major showcase is The Brutalist Playground Melbourne by artist Simon Terrill and the Turner Prize–winning London collective Assemble. Originally commissioned a decade ago by the Royal Institute of British Architects, the installation reimagines the forms of post-war British housing estates as climbable, touchable structures. In Melbourne, Terrill has layered in his own memories of growing up in Canberra, where the Griffins’ city design provided, as he puts it, a “teenage playground” of open space and concrete geometries. He described the project as a kind of return, bringing together the monumental modernist shapes of his youth with the playful invitations of Assemble’s work.

Alongside the newly commissioned works, Melbourne’s iteration of The Playground Project has secured a major coup in the form of Yvan Pestalozzi’s Lozziwurm, an iconic play sculpture first built in 1972. Its winding, worm-like body invites children to crawl through, climb over and slide down its twisting curves, embodying the idea of play as physical exploration and social exchange. The Lozziwurm is more than a temporary attraction: once the exhibition concludes, it will remain in Moonee Valley as a permanent fixture, offering generations of children the chance to engage with a piece of design history in the most direct way—through their bodies and imaginations.

The exhibition also embraces First Nations knowledge and creativity. A new playable public artwork by Trawlwoolway artist Edwina Green was unveiled on Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Country. Commissioned by Moonee Valley City Council in collaboration with the Agency, the work invites children to explore while reflecting on over 40,000 years of culture and climate. For the curator, this gesture resonates with her interest in do-it-yourself and community-led forms of play, which have long histories in Australia—from adventure playgrounds to neighbourhood initiatives such as Melbourne’s The Venny, a long-running community-built play space in Kensington.

Public programmes further extend the exhibition’s scope. A symposium on art and play—part of the Incinerator Gallery x MADA Talk Series brings together Featherston, Floyd, Burkhalter and Daniel Baumann (the Kunsthalle Zürich director who originally commissioned the project) alongside Monash University academics, to discuss the intersections of education, design and community. The conversations anchor the immersive installations within a broader discourse on how societies imagine childhood, risk and public space.

Burkhalter has been clear about her hopes for the children who visit the exhibition. “A key moment should be the opportunity to engage in free play outside of an educational setting,” she told STIR. “I understand that the concept of ‘risky play’ is important in Australia. But how can you take risks and be self-confident if parents and carers observe you with fear in their eyes? The exhibition and its play sculpture should encourage fearless moments of joy and play.” Her words highlight a paradox familiar to many parents: the desire to protect children while recognising that confidence comes from testing boundaries, flying leaps and taking chances.

The Playground Project ultimately reframes playgrounds as cultural spaces that belong to everyone. Councillor Ava Adams, Mayor of Moonee Valley, described playgrounds as the setting of formative childhood experiences in the press release and noted the pride the city takes in spotlighting the creative and social forces that shape them. The acquisition of the Lozziwurm, the commissioning of new site-specific works and the investment in a First Nations public art all signal a civic commitment to treating play as both heritage and future.

To walk through the Incinerator Gallery is to see the familiar language of swings and slides translated into sculpture, architecture and social commentary. Children are not passive recipients of these spaces but active collaborators—shaping them as they climb, crawl and invent games. What remains after the exhibition closes is not only the permanence of works such as the Lozziwurm or the Ringtales Playground, but a reminder that play, when taken seriously, can reshape how communities live together.

by Anushka Sharma Oct 06, 2025

An exploration of how historic wisdom can enrich contemporary living, the Chinese designer transforms a former Suzhou courtyard into a poetic retreat.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Aarthi Mohan | Published on : Oct 07, 2025

What do you think?