A lifetime in the city: How Lim Tze Peng documented a changing Singapore

by Ranjana DaveFeb 07, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Louis HoPublished on : Dec 26, 2024

The ecological future of the planet has emerged as one of the most crucial issues of our beleaguered 21st century, and the often uneasy, contentious balancing act that holds together the natural and built environments has been an abiding theme in Zen Teh’s practice. Her body of work reflects the dynamics of urban development and ecological sustainability in Singapore and, more broadly, Southeast Asia. For instance, In Between Spaces (2016) consists of a triptych of concrete panels with narrow strips of photographic images of the Rail Corridor in Singapore, suggesting the rapid and large-scale urbanisation of the island’s terrain. Teh, as she describes herself, is an artist and educator interested in interdisciplinary studies of nature and human behaviour, her practice spanning photographic, sculptural and installation formats. Her work has been part of numerous group and solo exhibitions, including those at the National Museum of Singapore and the Singapore Art Museum. In 2021, Teh was conferred the Young Artist Award, Singapore’s highest accolade for artists under the age of 35, and, more recently, in 2023, was featured in the third edition of the Thailand Biennale. Teh joined STIR for a conversation about her practice.

Louis Ho: How did your interest in natural ecologies develop? Singapore is famed for its carefully planned regime of urban use and green space; did that impact your practice?

Zen Teh: Having been born and bred in Singapore, yes, I’m accustomed to clearly defined spaces—areas designed for particular purposes. Yet Singapore is nested within Southeast Asia, which is a rapidly developing region—ecologically and culturally rich. My practice has been focused on environmental conditions in SE Asia for the past decade, where centralised control over the natural environment is limited, unlike Singapore. The tension between bureaucratic control and nature’s organic processes can be seen in the incorporation of plants and other organic matter in my work. I’m interested in using these materials to communicate embodied experiences.

Louis: That aspect is especially salient with one of your more recent public projects in Singapore, “Rattan Eco Sprawl: Manifesting the Forest”, which assumes the form of a monumental structure made of rattan.

Zen: It was completed earlier this year. It’s an interactive installation located on the edge of Spottiswoode Park in Tanjong Pagar. It was constructed by craftsmen in Cambodia. Its undulating forms resemble hills and mountains, as well as ant and termite colonies and features tunnels and overlapping doorways that draw inspiration from the gateways in religious monuments, such as Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom. Visitors should enter and experience the installation, while the permeable rattan walls provide opportunities for plants, insects and other non-human species to re-colonise the structure—which itself serves as a gateway, an in-between space that allows for the encounter of humans and non-humans, encouraging non-exploitative coexistence and collaborative forms of behaviour.

Louis: The work also intentionally incorporates live plants into its structure?

Zen: Indeed. Spottiswoode Park includes a secondary forest, and I collaborated with an ecologist, Dr. Chua Siew Chin, to select native species of plants based on their compatibility with the site’s environment. I’m hoping the work functions as a restorative initiative, attracting wildlife to re-inhabit and improve the ecology of the forest. It’s surrounded by a residential neighbourhood and isolated from other ecological networks and natural spaces on the island.

Louis: You mentioned religious monuments earlier. Your work in the Thailand Biennale 2023, notably, was sited in a temple in a Buddhist retreat. Tell us about it.

Zen: I wanted to consider our spiritual yet embodied connections with the natural environment and people’s experiences with the land in northern Thailand (where the biennale was located). I devoted 45 days to topographical mapping, interviews with local communities and also used meditation as a mode of research at various sacred sites.

Imperative Landscape (2023): Astronomical Alignments became a collaborative project with a local astronomer, Dr. Momay, from Chiang Rai Rajabhat University. The work was an immersive, multi-component installation that included images of Chiang Rai’s periphery forests printed on meditation seats and 300 ceramic pieces inspired by the drawings of the Buddha’s eye. These pieces were individually hung from the ceiling and aligned in the space through precise astronomical calculations. I was inspired by the experience of meditation and the connection with forces larger than ourselves. Accounts from the interviews I conducted suggested the power of spirituality to motivate the transcendence of the every day and even the meaning of the beyond – i.e. the afterlife.

Louis: 2023 sounds like it was a busy year for you. You were also involved with the Künstlerhaus Bethanien residency program in Berlin, which is supported by Singapore’s National Arts Council. How did you translate your interest in ecological realities into a dense, urban context like Berlin’s?

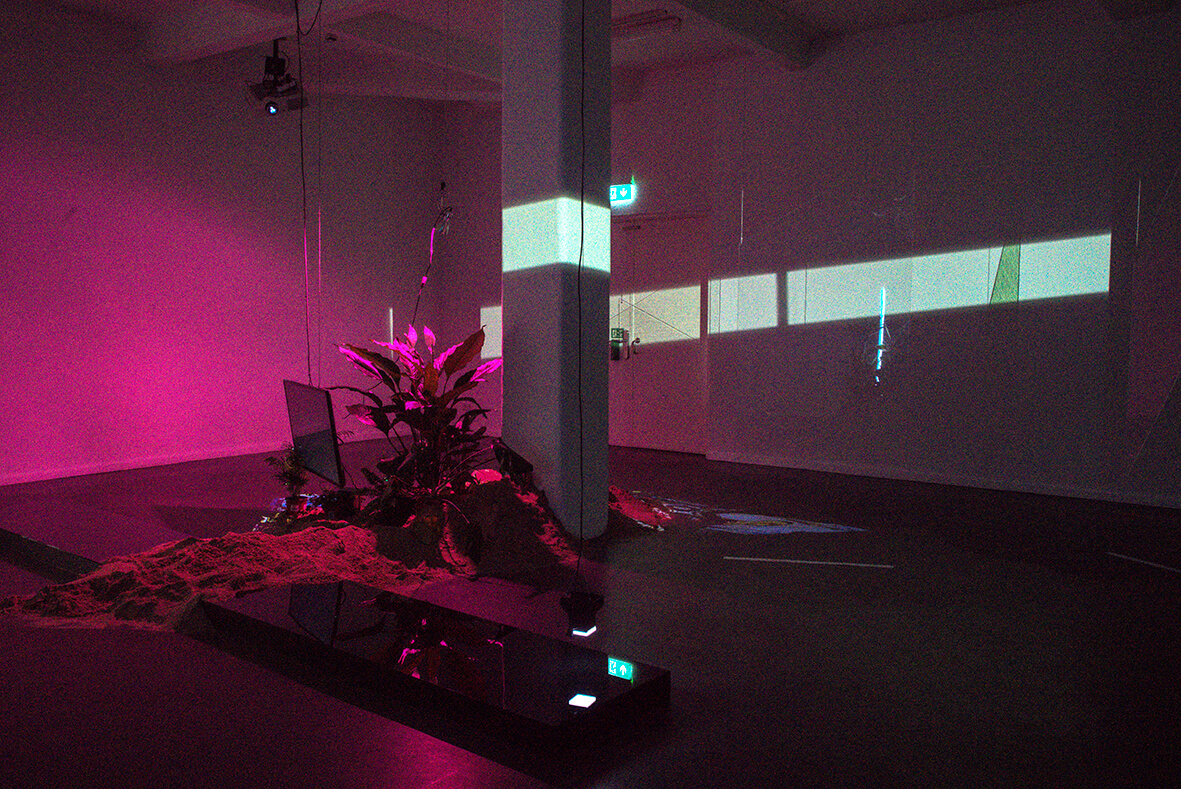

Zen: My Künstlerhaus Bethanien project, Swallowed by Darkness, draws from a shared discourse on light and urbanity and the phenomenology of light generally. The project involved night walks through Berlin, as well as cities in SE Asia, including Bangkok and Phnom Penh. The information generated from the analysis of collected light data will inform a multimedia installation featuring live plants, drawing information from participants’ responses to these walks. Experiences were recorded as voice recordings and photographic images. The presentation took place in Berlin and will be restaged in Singapore during Art Week next year.

Light is also, of course, more than just a bodily experience. Its access, and pollution, are framed by political, economic, social and environmental contexts. It’s a technological marker of productivity; developed nations have marginalised darkness and enabled round-the-clock work patterns. Consequently, urban development continues to affect biological beings, shaping the identities we hold in relation to environmental changes. The control of the amount of light is also related to the accessibility of energy. In view of the war in Ukraine and the energy crunch, the world has become increasingly divided in its usage of energy.

Louis: One common thread that seems to run through your practice is its collaborative and research-led aspect.

Zen: Yes. An earlier series from 2017, Garden State Palimpsest, involved working with an architectural researcher to conduct interviews with former kampung (village) residents in Singapore as a way to understand the changes in the island’s terrain from the 1970s to the 1990s. In 2019, I undertook a residency at Selasar Sunaryo Art Space in Bandung, Indonesia, which culminated in a body of work that explored the impact of urbanisation in the area on its geomorphology. My primary collaborator was an earth scientist from the University Padjadjaran, and the outcome was a travelling exhibition, Mountain Pass: Negotiating Ambivalence.

Upcoming collaborations include projects with Berlin-based Malaysian dancer SueKi Yee and Cambodian artist Lim Sokchanlina, where we reflect on environmental issues along the Mekong River.

Zen: I recently wrapped up my M.A. at Singapore’s National Institute of Education. Current projects include extending the Berlin work to Singapore Art Week in January 2025, on which I’m working with Yee, the dancer; it will also later travel to Finland for a group residency with her and a Cambodian collaborator, Siden. The Thailand Biennale piece also gained traction in Japan, so I have also been invited to participate in the upcoming Setouchi Triennale.

I am bringing the second iteration of Rattan Eco Sprawl to Berlin. I would like to explore how rattan architecture can serve as a space for knowledge sharing. I need to consider the circularity and sustainability of my work as an artist interested in environmental issues, so there are plans to donate the work to Cambodia after the exhibition to function as an art centre for local communities.

‘Rattan Eco Sprawl: Manifesting the Forest’ is on view at Spottiswoode Park until December 2025.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Louis Ho | Published on : Dec 26, 2024

What do you think?