Fiona Tan curates a cabinet of fixations in Monomania at the Rijksmuseum

by Hili PerlsonJul 10, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Vladimir BelogolovskyPublished on : Apr 05, 2024

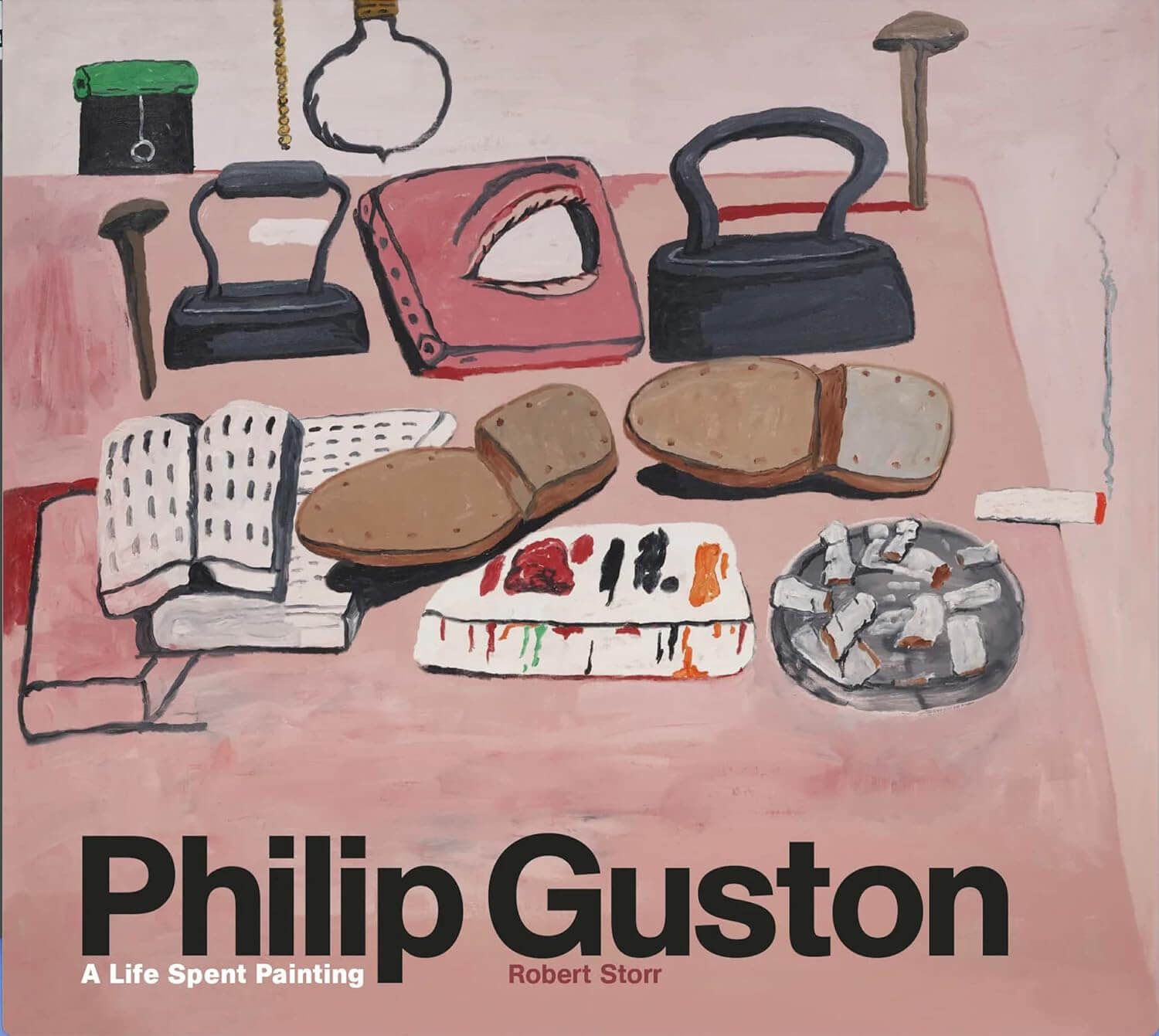

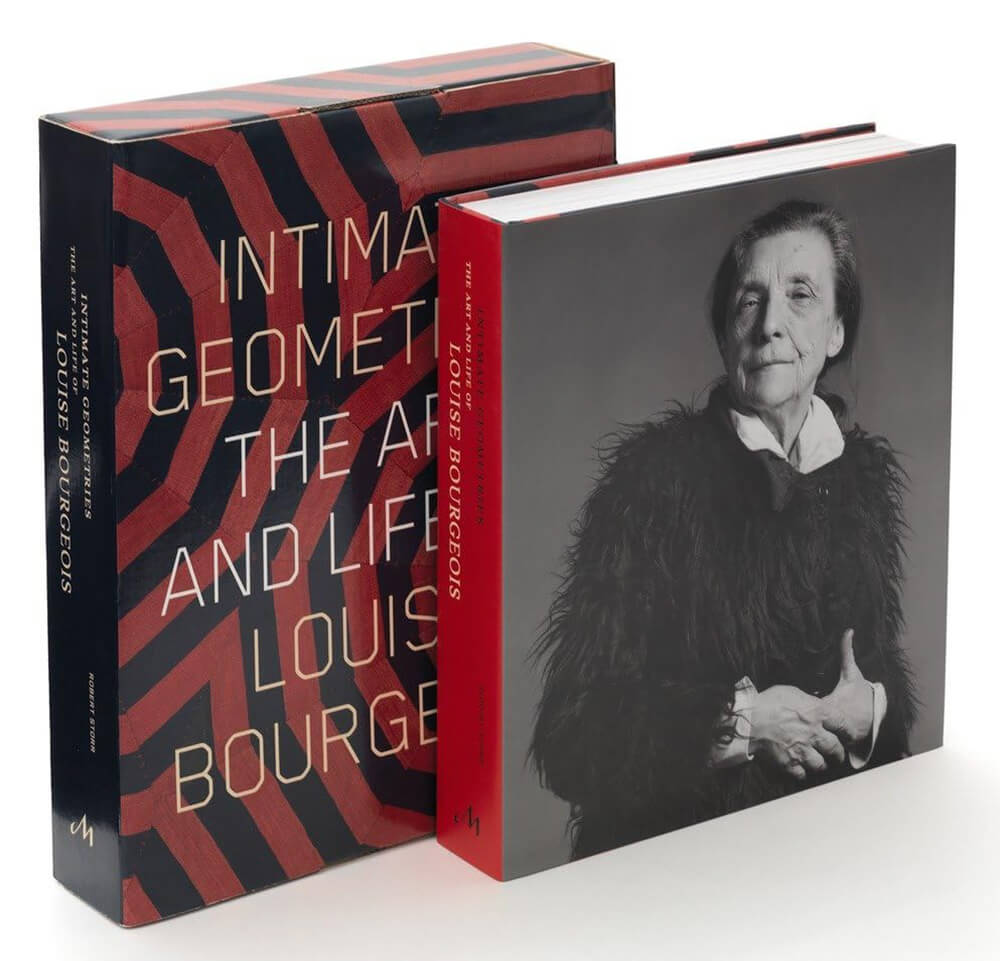

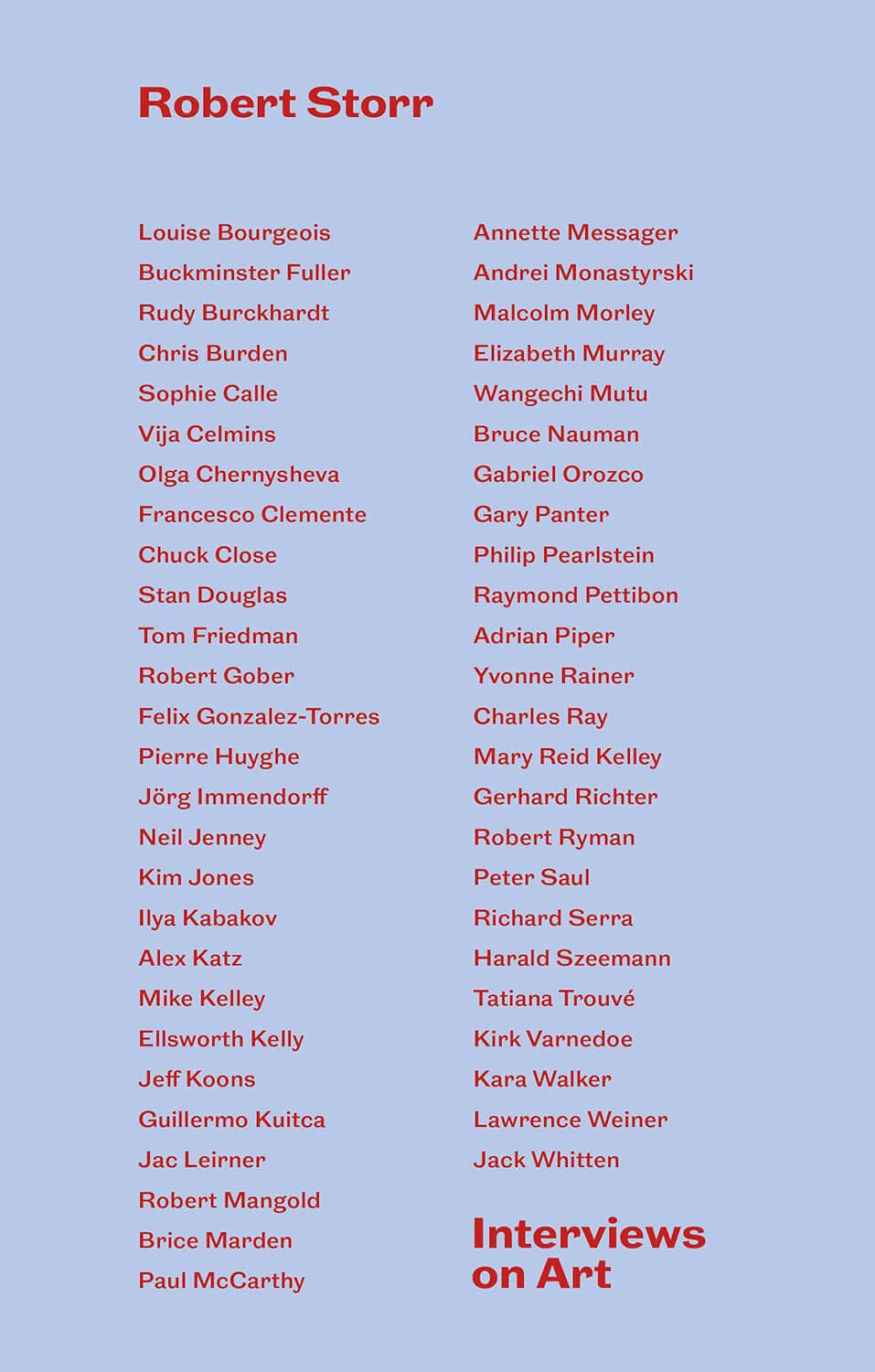

Curator, art critic and painter Robert Storr did not paint until graduate school but drew all the time ever since childhood. He explains his early love for drawing by being dyslexic and having a very hard time reading. “Drawing pictures was my way to communicate with the world,” he told me during our conversation. His authored books include monographs on the works of Louise Bourgeois, Chuck Close, Philip Guston, Ellsworth Kelly, Gerhard Richter, Robert Ryman and a collection of Interviews on Art featuring many of the most influential artists of the second half of the 20th century. Last year Storr gifted his vast library and archive—25,000 volumes—to the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. The curator pursued the history of art on his own by reading and talking to artists and historians, as well as by teaching art history.

Storr was born in 1949 in Portland, Maine where his father was teaching at the time, but grew up in Chicago. His family is packed with historians, including his parents, sisters and their husbands. "As you can imagine, at the dinner table, history was discussed all the time,” he quipped. Upon finishing high school at the age of 19 Storr went to study at Elysée, a small Protestant college in Southern France where he spent a year. It was 1968, the year that the country was in turmoil; Storr was recruited as an international representative to take part in student protests. Half of his time was spent studying French history and the other half on discussing politics with friends.

After coming back to America, Storr continued his interest in French literature at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, earning a Bachelor of Arts in 1972. He then studied painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, receiving his Master of Fine Arts in 1978, the year his first art review was published in the New Art Examiner. His frequent publications in Art in America, Artforum and other leading art magazines, led to his invitation in 1990 to join the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York; he eventually became the department’s senior curator. One of his highlights was the 1991 Dislocations show featuring new installations by seven artists. After leaving MoMA in 2002, Storr taught modern art at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, Rhode Island School of Design, Harvard, and for a decade, from 2006 to 2016, he was the dean at Yale School of Art. In 2007, Storr served as the director of the 52nd Venice Art Biennale which he titled Think with the Senses, Feel with the Mind.

Vladimir Belogolovsky: You were first introduced to artists by being invited to parties in New York by your great-aunt, an art collector and socialite, Elizabeth Chapman, known as Bobsy. I read that she took you to a party where you met Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, (Frank) Stella, Claes Oldenburg, Lee Krasner, George Segal, Jasper Johns, and some others all at once. Can you tell us more about that?

Robert Storr: That’s true but also, I worked at the Video Data Bank at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, one of the first projects to interview contemporary artists. I worked on gathering material for these interviews which was my entry into the contemporary art scene. I was in my mid-20s then. As part of my work, I would commute to New York to visit artists in their studios to collect images of their work for these video interviews in which they would be featured as background slides.

The party you refer to was at Bill Rubin’s [William Rubin] house in Downtown Manhattan. It was very exotic and it had a huge impact on me. I was still a teenager then. Bobsy was my mother’s aunt. She was a very colourful character and a bit estranged from the family because she married a wealthy man and became a rich woman. She was outstanding and ran the Arts Club of Chicago and was a prominent patron of the arts. She went to Europe at least once a year to see exhibitions and concerts and invited people to come to perform or show their work at this private club. Thanks to her I continued coming to New York and meeting lots of people at galleries. We kept in touch for about a decade before she died in her late 80s.

VB: How was your student experience in America? Did you plan to commit to becoming an artist?

RS: In Chicago, I became close to two women who ran a bookstore called Green Door, which has since closed. They had the most amazing clients to whom they sold a range of books. My real education took place in that shop, more than at school. My sense of learning about how the world was organised was especially from meeting people who came there to buy books. There was no art programme at Swarthmore but I had very extensive conversations with some of the art professors there and I was hungry for more. Once I got out of college, first I went to Boston where naturally, I did the same thing. I worked for a bookseller in Cambridge called Schoenhof’s Foreign Books. And at night, I would take drawing classes at the Museum of Fine Arts School. I lived nearby, behind the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. That’s how I made a living and educated myself in the process. At the bookstore, I met some painters and Harvard professors. We went out for lunch often and that was an important education for me as well. I also worked as a teaching assistant in exchange for taking courses. All this time I was doing my art. For the first 10-15 years, I was a figurative artist and then I focused on abstraction.

VB: When and how did the idea of curating exhibitions occur to you?

RS: Making exhibitions was a total fluke. Parallel to my studies and art career I was writing occasional exhibition reviews for art magazines. Years later when I was already living in New York I saw an exhibition on the works of Philip Guston which I liked enormously. I had been thinking about his work for quite some time. So, when I saw a disparaging review of it in The Village Voice by critic Peter Schjeldahl, I wrote him a very long letter about why he was full of s***. [Laughs.] Then he wrote me a long letter saying that they don’t normally publish letters of such length. He said, “You, however, are also full of s***. But you know something, you can write pretty well. Would you like to write for me in The Voice?” That’s not what I wanted to do, so I declined. Then we met for drinks. He proposed again. I turned him down again. He was angry because he probably thought he found his protege. But I was not a protege material. I was my own man. Then, in frustration, he sent my letter to Elizabeth Baker, the editor at Art in America and I agreed to write for her, which I started doing in 1982. But none of that involved curation.

VB: So, how did you get into curating then?

RS: I continued writing, teaching part-time at art schools along the East Coast and doing some construction work. Along the way, I did two or three small exhibitions. Then Kirk Varnedoe, the Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture at MoMA who did not see any of my shows but read my criticism invited me to join the department. That was in 1989. He wanted me to be his second in command. I didn’t think I was ready for it and I didn’t want something that would take me from my work, so I said no. Shortly after I was asked to interview him for a magazine. I agreed and at the end of that interview he offered me the same position again and I declined again. [Laughs.] Then he asked me to contribute a text for the catalogue of his High and Low: Modern Art And Popular Culture, a major show at MoMA in 1990. He edited that essay and while editing that piece, he asked me for the third time if I would join the museum. By then I said, “OK, fine, I’ll give it a shot.” [Laughs.]

VB: What was the main intention of your Dislocations (1991) show at MoMA with new installations by Louise Bourgeois, Chris Burden, Sophie Calle, David Hammons, Ilya Kabakov, Bruce Nauman and Adrian Piper?

RS: That was the main intention—to make it very diverse! At the time, MoMA was locked into a very predictable pattern of doing certain things by picking only the top artists. So, I decided that if this was my shot then I would break the mold and I would show something that they did not focus on, which was installation. I wanted to show what these people were doing and that they were doing it differently. It was about diversity and pluralism.

VB: Christian Boltanski said, “We only remember exhibitions that invent a new rule of the game.” And Richard Hamilton said, “We only remember exhibitions that invent a new display feature.” Do you agree?

RS: They are both partially right, just as all categorical statements are only partially right. Display features are for sure important. For example, for the Venice Biennale, I tried to turn the whole Arsenale into a singular unpartitioned space; there were curtains between the columns, not across the whole space from wall to wall. It did not work entirely but it was pretty successful. As a result, a lot of people complained that the space wasn’t museum-like. But that’s not what I intended. The point was to unify the space and let viewers wander through it, like in a bazaar souk.

VB: What kind of exhibition is successful for you?

RS: The one that encourages unpredictable participants. The one that triggers multiple conversations. The one that brings in fresh artists, not celebrating trademark art. Also, in my shows, I try to avoid making a polemic. Polemical exhibitions never succeed as art exhibitions and they rarely succeed as polemics.

VB: What kind of works catch your attention and why?

RS: The ones that are fresh, problematic and that I don’t initially like. If there is something that you don’t like at first, it probably has something that goes into the core where your questions are and so you don’t like that core being touched. It exposes the nerve. And I don’t like such criteria, whether I like something or not, because liking is a weak emotion. Generally, I don’t like art that proposes the ultimate answer to the ultimate question. However, I am fascinated by things that have hard-driving interior motivation and that tackle difficult questions. In other words, I like art that’s imperfect. I like art that fails on some level. Again, I like things that are risky. I like the work by Brooklyn-based painter and sculptor Dana Schutz. She works both in painting and clay and she is biting more than she can chew but she is biting it off and she is driven by an entirely honest, brave and adventurist voice. The fact that she doesn’t wholly succeed doesn’t bother me. I don’t expect anybody to wholly succeed. [Laughs.] I am interested in the risk that she takes and how far she gets, given what she is tackling. I learn a lot from her.

VB: Painter Robert Ryman told you in one of your interviews that a painting is about the experience of delight, enlightenment, and fulfilment. What do you think a painting is about and what is the purpose of a work of art?

RS: That is the case for Bob and his work does that. He achieves that with a remarkable regularity. His paintings are dazzling. He was true to his work. He was true to his ambition. For me, it is more open than that. Art causes you to think and feel simultaneously, which is the essence of my Biennale’s title in Venice, Think with the Senses, Feel with the Mind. I want people to think and feel simultaneously. If I feel something powerful then I know I need to think about it again. And if I think something is powerful, I have to ask, “What does it make you feel?”

VB: What is your way of teaching art?

RS: What I try to do is pick a topic rich in questions that could not readily be answered. I want to present arguments and examples on both sides to avoid coming to a neutral position. The idea is to consider opposite positions. The point is to bring people to a state of mind to imagine fully how to experience and smell a work of art. Look, I was a realist painter; I am an abstract painter now. I was on the left politically; I am not on the left to that extent and I understand people who are on the right. People should understand art as real choices, not logical ones. To be logical is too easy on the soul and if the soul is not involved nothing you say matters.

VB: In architecture, both the role of an individual and the role of a building as an object are on the decline. Can the same be said about art?

RS: First of all, ‘the decline’ is a negative term. One can say there is less of it or there is more of it. There were periods when art was made by individuals or by collectives, as was the case in the 1920s. Individual makers were not celebrated for their genius then. The point was to have something fresh and valuable. It must be viewed as a positive thing. This happens from time to time both in the art world and in architecture. Celebration of an individual architect’s style can be a problem. But my interest is not in the architect but rather in the building.

VB: Well, the current interest is not in the building either. It is about demanding it to be more than an object. It must solve problems and bring value to the community. A building as a work of craftsmanship, originality, beauty, or sculptural qualities is on pause.

RS: Do you think that it's true? Is it universally true or just for some people?

VB: I think there are enough people who want to believe that it’s true. There is a lot of scepticism in private conversations. But in public, there is enough support to make it appear as if there is consensus. There is a lot of alignment in the discipline.

RS: Well, the difference between art and architecture is in the question of utility. Architecture is supposed to be useful. Art may be useless. It is not easy to do. People think it is easy. It isn’t. But in the case of architecture, why architecture should solve problems that no one else can solve? The utopian ambition of artists and architects is a feature of modernism and I accept it for what it is but I also think it is folly. Richard Serra said to Chuck Close when they were still students at Yale, “People talk about solving problems in art? I don’t think we solve problems. I think we create them.”

VB: What’s your view on Modernism? Would you say it is an ongoing condition to be modern or does it have a beginning and end?

RS: Modern European history refers to the late medieval Renaissance. Modern is not inherently the 19th and 20th century condition. And I don’t think anyone can speculate when Modernism came to an end and when Postmodernism began. These are just things that alleviate the need to be historically engaged. I think the conditions for Modernism have developed at different paces in different ways and in different parts of the world. So, the most appropriate way to discuss these issues is to ask these questions but without presumable answers. What is modern in Africa currently? What is modern in South America currently? What is modern in Asia currently? And I don’t think there is an ongoing Postmodernism. I think it is wishful thinking of the people who want to be done with the misery of Modernism. Modernism was pronounced dead too many times. It is not over. Being modern is being modern at the moment being contemporary. Modernism has become a period label. I don’t subscribe to that.

VB: And what do you think about Postmodernism? How relevant is it now?

RS: I think Postmodernism was fiction from the get-go. It was a way of dealing with the shocks of the period of 1968 and after. It was a way of accepting the fact that the old left had died but the new left is yet to be born. Antonio Gramsci, an Italian Marxist philosopher famously said, “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.” This is the time we are in now. And it has been for quite some time. Everything in post-1968 is in that limbo.

VB: And finally, could you elaborate on your quote, “Making art has made me a better curator. Whether or not being a curator has made me a better artist remains to be seen.”

RS: I need to make the art that will tell my tale and I have yet to do it. I’ve done some things and I hope to do more. I need to live long enough to see if I am capable of doing the work that I think I am capable of doing. One week I curate exhibitions, trying to make sense of the work of others and the next week I do my own art. I take energy from one activity and put it back in the other.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

by Ranjana Dave Oct 03, 2025

Bridging a museum collection and contemporary works, curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath treat ‘yearning’ as a continuum in their plans for the 2025 Taipei Biennial.

by Srishti Ojha Sep 30, 2025

Fundación La Nave Salinas in Ibiza celebrates its 10th anniversary with an exhibition of newly commissioned contemporary still-life paintings by American artist, Pedro Pedro.

by Deeksha Nath Sep 29, 2025

An exhibition at the Barbican Centre places the 20th century Swiss sculptor in dialogue with the British-Palestinian artist, exploring how displacement, surveillance and violence shape bodies and spaces.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Vladimir Belogolovsky | Published on : Apr 05, 2024

What do you think?