Phyllis Birkby’s lesbian feminist architecture and the probing of fantasy as resistance

by Mrinmayee BhootJun 20, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Aug 14, 2024

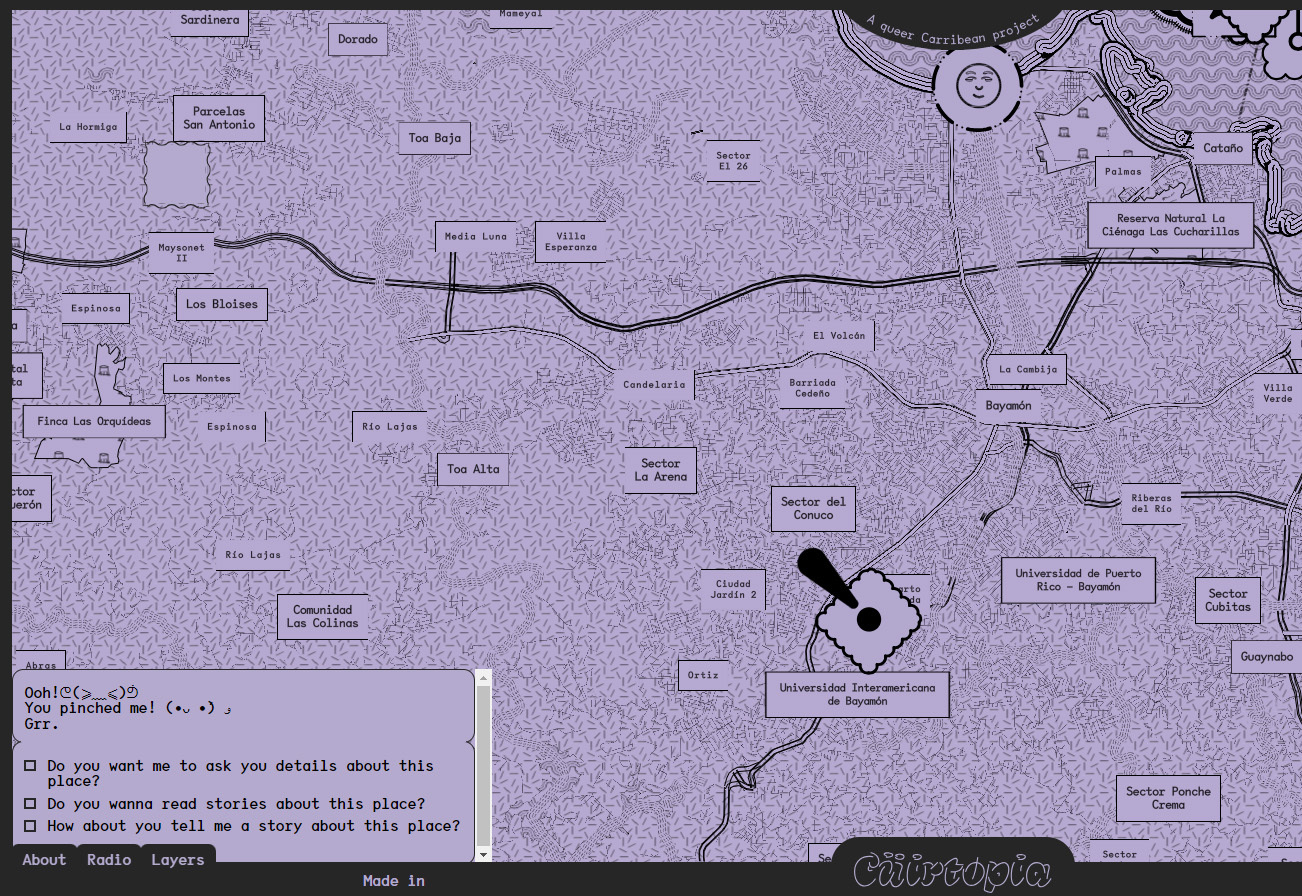

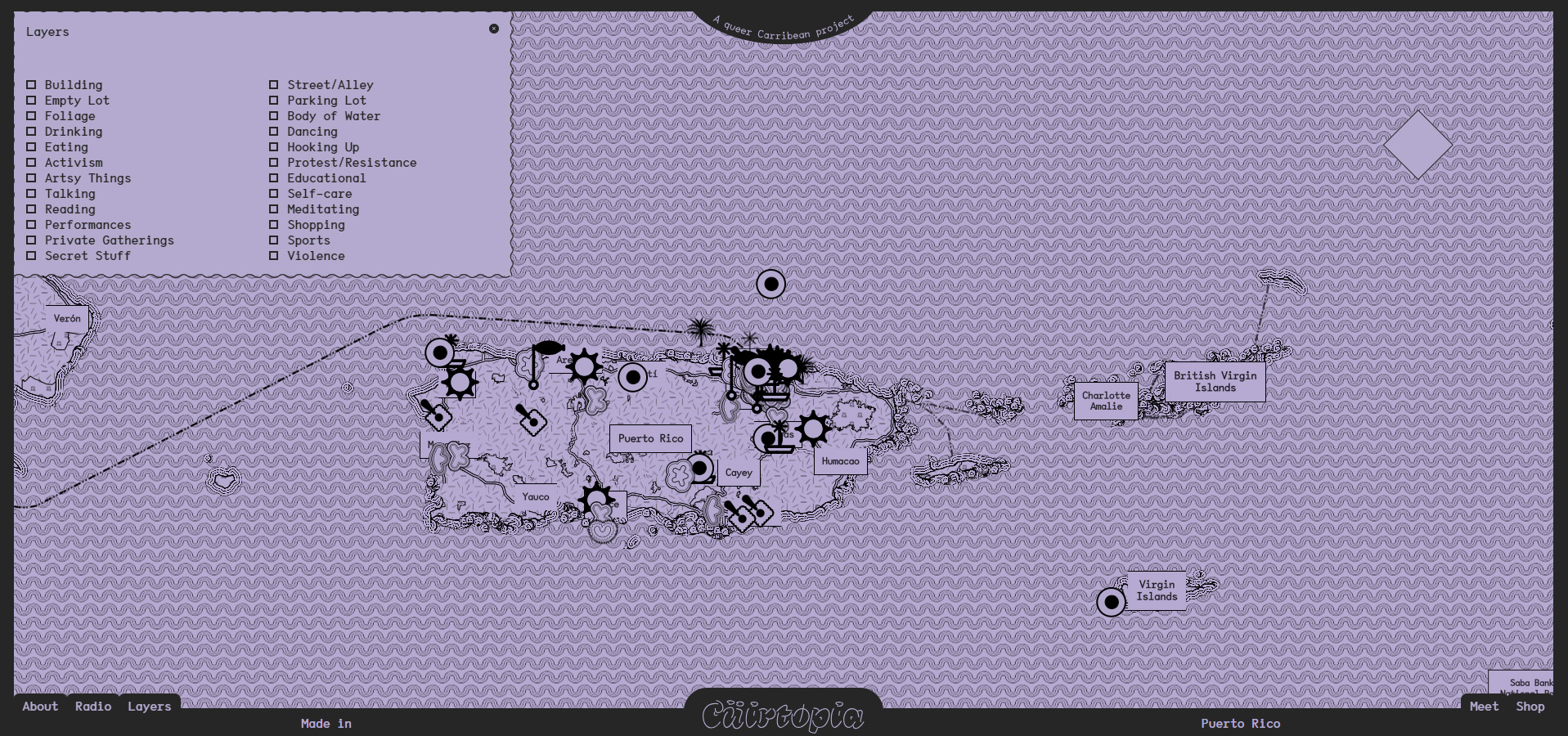

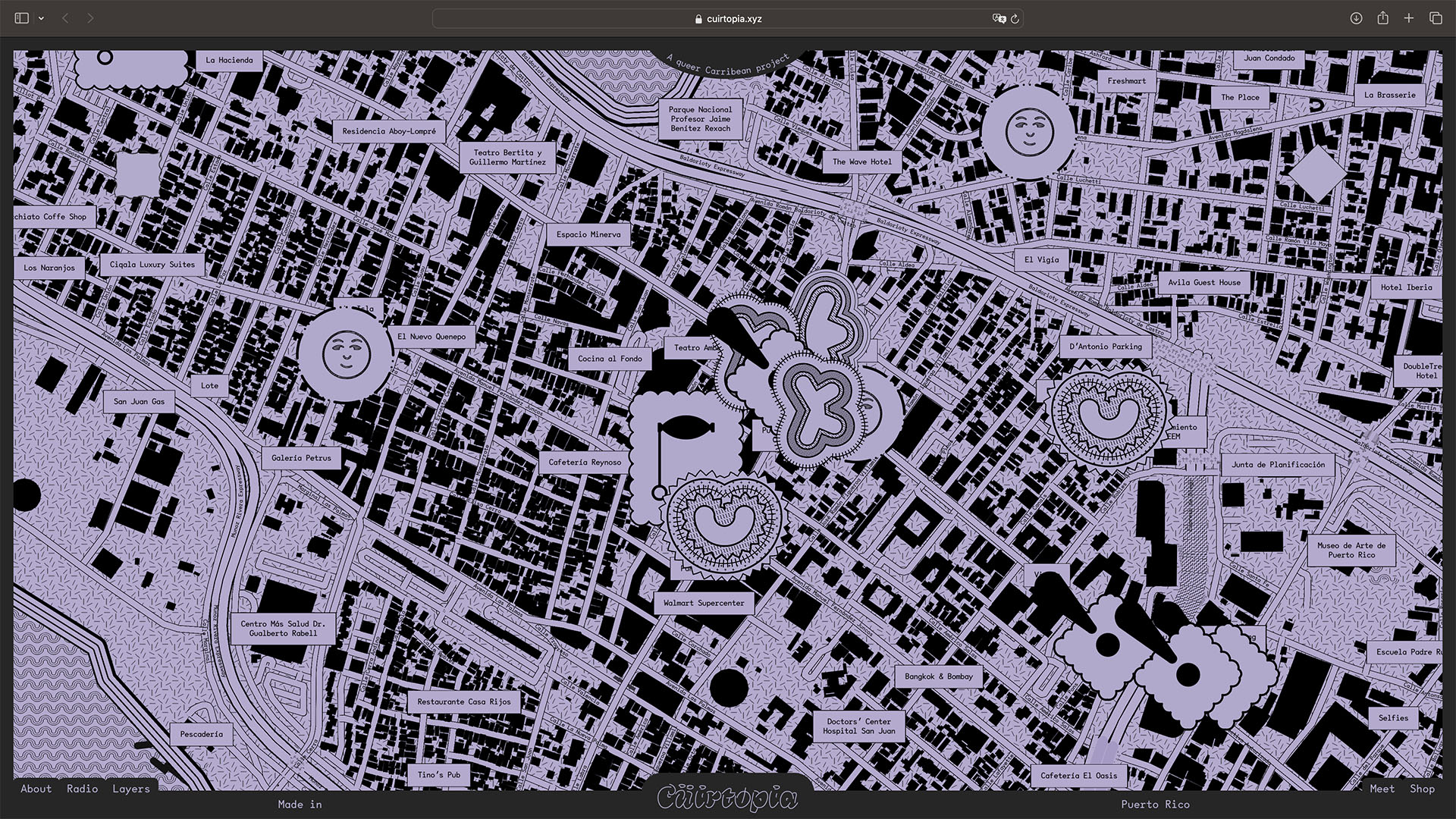

A map presented in front of you, rendered in lilac, depicts the outline of the Caribbean islands. As you zoom in and out, scrolling and playing with the interactive design of its interface, an avatar, Konpa, guides your explorations revealing different layers and different stories. Somewhere near Sector Bechara is the Esechys, a lesbian nightclub. Somewhere near sector Camilla, a housing project by an NGO that works with survivors of domestic violence. Elsewhere, the map labels Lares, the Peasant Agroecological Project; 'queer spaces where everyone can come together,' the map's text asserts. Stories of surviving, belonging, violence, protest, resistance, of coalescing in Cüirtopia, a research project led by Dr. Regner Ramos, an architect and academic from Puerto Rico, reimagine “how we register, represent, and document queer spaces in the Caribbean.”

Navigating multiple layers of cartography, storytelling, and queer identities; the project—described as both an archival artefact and a speculative research method—focuses on the cartographic representation of queer architectural and urban history. Through this, it hopes to challenge limiting dominant narratives—often heteronormative, often white—that erase or other LGBTQIA+ lives. Different iterations of the research undertaken by Ramos include an exhibition at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Puerto Rico; a short film which was showcased at the MAXXI in Rome; an ongoing radio show; a fictional story told via Instagram; community events; site-based installations; a forthcoming book by Ramos and another upcoming exhibition at Triennale Milano.

Laying out a fitting way to write concisely about a topic this specific ought to be easy: you begin with maps and their claims of organising, documenting and classifying the world. “Maps do not just make the world. They help make other worlds, and the worlds of others," writes Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther in When Maps Become the World. By its very nature, cartography submits to a binary view of the world, a view of the world that believes it can be categorised, claimed and hence controlled. You write about the fact that the very idea of categorisation and control depends on who is doing the telling, and who gets to tell what stories. That then, a map presents a view of the world that conforms to one particular way of being.

You write about queerness, conditions of being that undo what is acceptable or “normal.” Adopting a queer perspective on anything means embracing multiplicities, rejecting categorisation to engage with the muddiness of life, and developing new kinships. You acknowledge that the very existence of a queer experience in a space queers it, an idea that manifests in Canadian designer Lucas LaRochelle’s online resource Queering the Map. On the other hand, queer space is also a place where the queer identity thrives, a space of affirmation and community, a refuge that can manifest in private or public spaces: in places of protest, on a park bench, a club, or even a train as documented in Adam Nathaniel Furman’s Queer Spaces.

That these projects engaging in mapping, documenting and archiving LGBTQIA+ experiences outside the official narratives of History—relying instead on stories shared by people—are acts of resistance against the status quo. To paraphrase Joan Didion, we tell stories in order to (re)claim our lives.

[Queerness] is not about standing within a binary, but about permeating, oozing in and out of, pressing against. I think categories are just ways to organise the world, to make it decipherable to the status quo, but queerness is the opposite of that. – Regner Ramos

As the website for Cüirtopia notes, by recognising and enumerating LBGTQ+ spaces within contemporary cartographic practices in the Caribbean, the project queers the ‘objectivity’ of “architectural history, cultural infrastructure, urban memory” and lays claim to a more inclusive political future. On practices of countermapping as an act of rebellion, and the notion of queering spaces and storytelling, STIR spoke to Regner Ramos about his ongoing project.

Mrinmayee Bhoot: A lot of your research revolves around mapping and documenting LGBTQIA+ spaces and buildings in Puerto Rico. Could you tell us where your interest in mapping practices and archiving stems from?

Regner Ramos: My interest in mapping stems from my childhood and found its way into my practice as an architectural researcher. I think back on RPG games on my Super Nintendo or my Gameboy—Mario Bros, Pokemon, Donkey Kong—and I always found the aesthetic representation of locations to be so beautiful, colourful, and full of life.

When I started researching LGBTQIA+ spaces in Puerto Rico, two figures helped me conceptualise what would become Cüirtopia: Luchas LaRochelle and their project Queering The Map, as well as Javier Laureano and his book San Juan Gay: Conquista de un espacio urbano de 1948-1991. While Lucas was quite literally queering a Google map so people could write stories of moments and intimate experiences located throughout the globe, Laureano had written a historical archive of important LGBTQ spaces in Puerto Rico’s capital city. I thought where I could contribute was to position my project somewhere in the middle.

Mrinmayee: Building on that, could you elaborate on what “queer space” denotes for your practice?

Regner: In my research, I use “queer space” to talk about a particular location—a room, a building, a street, an outdoor area—that for any given reason is used/inhabited in such a way that challenges traditional, heteronormative ideals. I’m not necessarily interested in defining what a queer space “is” because I think queer is useful as a term that does the opposite: it undefines things, makes them messy, complex, and entangled. I’m more interested in finding queer uses and readings of space, which opens up a broad range of practices and spatial typologies. In that sense, and my work, a queer space could be something as conventional as a nightclub as well as something as speculative and theoretical as a scientific radio telescope facility in the forests of Puerto Rico, used to send a binary-coded message to a distant galaxy – which is the film I made for the MAXXI in Rome.

I wanted to bring out stories that thought about LGBTQ spaces as much more than just bars and capitalist spaces but also include grassroots efforts, agricultural spaces, educational spaces, religious spaces and ephemeral events, among others.

Mrinmayee: There’s a delightful sense of in-betweenness to the project overall: playing with fact and fiction, history and storytelling, the virtual and physical. I was wondering how you would classify a project like this. Could you perhaps comment on how this liminality between digital communications and physical structures plays into the reimagination of architectural spaces through a queer lens in your project?

Regner: That’s exactly right, Cüirtopia exists in the in-between because queerness itself is a liminal issue. In Puerto Rico especially, it’s pointless to try to separate physical spaces from digital spaces when it comes to queer people. Digital devices and the internet have been vital tools for how the community has found each other and constructed their identities, myself included.

Reading feminist trailblazers like Donna Haraway, Rosi Braidotti, and N. Katherine Hayles helped me break free from the idea that knowledge is produced objectively, what Haraway calls the “god-trick” of seeing everything from nowhere. Instead, these theorists encourage us to acknowledge our multiple positions in the world and everything that entails—be it the kind of body we inhabit, our gender, sexuality, cultural upbringing, or educational background—as the modes by which we produce knowledge. I was also influenced a lot—produced from my subjective position evidently in the project—by the work of brilliant architectural thinkers like Jane Rendell and her ideas on “site-writing”.

I remember seeing music videos at night when I was a teenager. In the '90s and early 2000s, one could send messages that would scroll over the videos, and I remember messages from men looking for other men, anonymously writing what they were looking for; in part because they might live in small towns where there were no other men around or perhaps because they were closeted and couldn’t come out. Fast forward to today, and there aren’t that many queer spaces to begin with, so it’s a relief to have social media apps that keep us connected to a larger community on the island.

Mrinmayee: Considering a site like Puerto Rico, which is laden with a colonial history, were these histories of exclusion and erasure of queer bodies important to creating the map? What stories did you think were vital in telling queer histories of Puerto Rico?

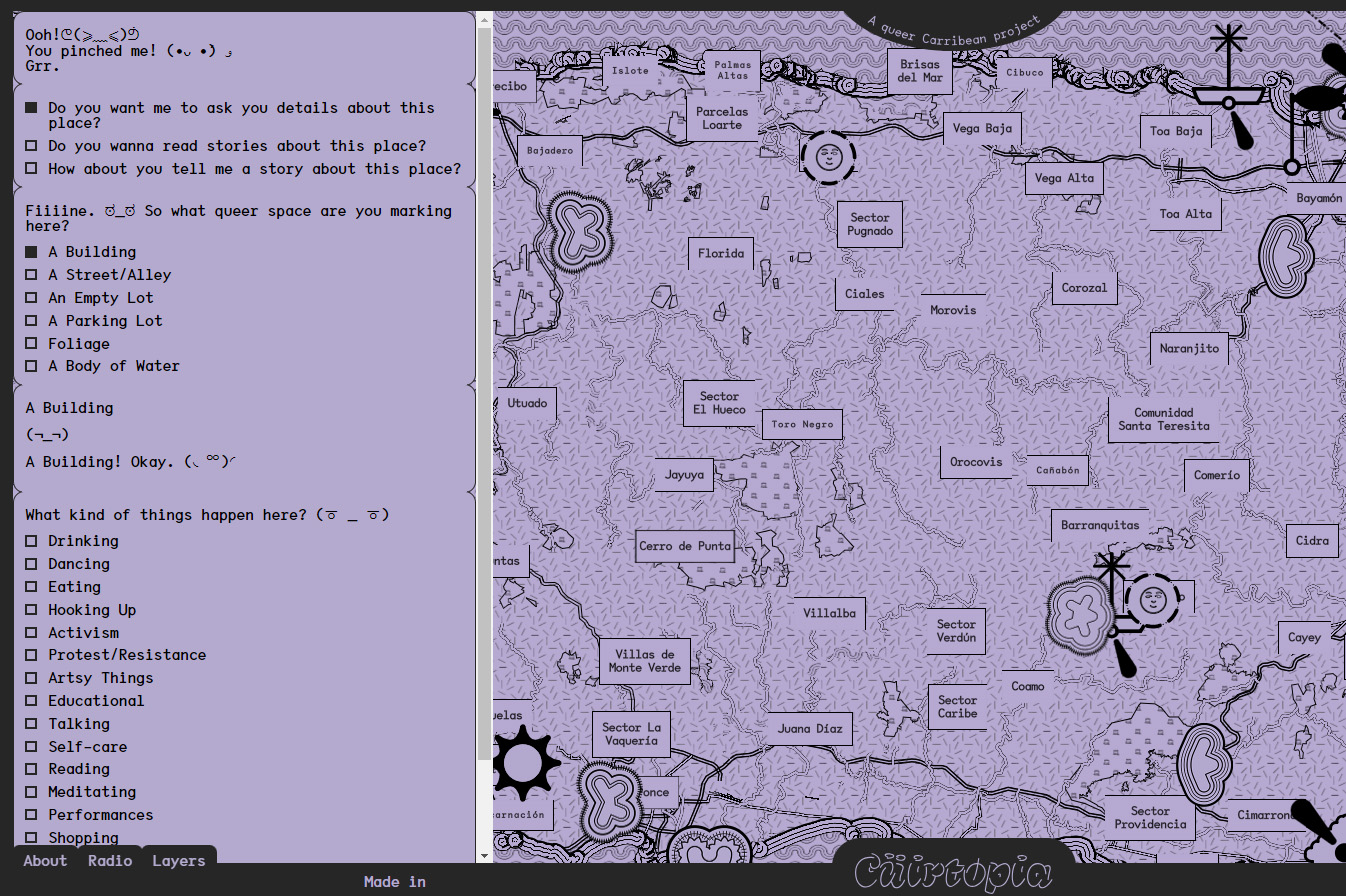

Regner: Before Laureano’s book, there was no other academic register documenting where LGBTQ spaces were located, what they meant to people, how they came to be, how they related to their contexts and what needs they were fulfilling. Architectural history has ignored these spaces, so my question was, how do I address this? What methods can I use to insert them within architectural discourse? Mapping was one way to do it, but another method was via oral storytelling.

In my research project, when I interview people on my radio show/podcast, I’m looking for personal stories, in an attempt to challenge the idea that in Puerto Rico, architectural history needs to be written by academics that corroborate information in archives and books. Our queer architectural history must be told through the voices of many. I’m not looking for one single truth, but multiple versions of it. Lies, gossip, exaggerations, hyperbole included. Isn’t that a richer project? Isn’t that a more accurate representation of queer life?

I wanted to bring out stories that thought about LGBTQ spaces as much more than just bars and capitalist spaces. I wanted diverse typologies and scales of spaces. The fact that the map is designed so that anyone can mark/register a space is my way of allowing people to actively create our architectural history. This is why I always go back to the method of storytelling, not historicising. My upcoming book—Cüirtopia: Puerto Rican Stories of Queer Spaces—is precisely that, a compilation of those stories people have told me on the radio.

Mrinmayee: On that note, how did you decide what’s important to be included and what’s not? What can and cannot be mapped — and maybe what should not be recorded on a queer map?

Regner: I don’t filter out which stories get told and which don’t. However, Cüirtopia is a project about spaces. That’s the spirit of it, that’s what’s vital, that’s what’s unique about it, and to a great degree, that’s the filter, if there is one. I do my best to ensure that the stories Cüirtopia tells are linked, even if loosely, to issues of the built environment, buildings, architecture, and landscapes.

To your second question, one of the main concerns I thought about early in the project was: How do I map these spaces without making them vulnerable to attack, especially if people were to use the map in more queerphobic places in the Caribbean? How do I enable people to mark the spaces that are important to them, without making them identifiable and locatable? The solution I came up with was that Cüirtopia would be a map of approximate areas, not a map listing the coordinates of a building. There are intentional limits to how close you can zoom into the map.

Ironically, the more spaces are mapped out in a general vicinity, the messier the map becomes. For instance, if you zoom into the Santurce neighbourhood of San Juan, you’ll see a clash of marks on the map. In this sense, the more stories get mapped, the more protected the area becomes. It’s one of my favourite features.

When a visitor visits cuirtopia.xyz, no matter where you’re from, you always will land in Puerto Rico. So many times, because of the size of the islands, Puerto Rico gets left out of maps. In Cüirtopia, [the] scale of the Caribbean is the norm. If you try to zoom out too much, the map resists because it’s not that the Caribbean is too small, it’s that the rest of the world is too big. Getting lost is part of the experience.

Mrinmayee: I’d also love to know more about the graphic design and visual identity of Cüirtopia: the simple icons, the ASCII emojis that Konpa uses, and the particular shade of lilac. How did you decide the look of the project?

Regner: I wanted visitors to connect with the map as an artefact, not have it feel like boring research. I was inspired by the formal language of architectural drawing—lineweights, hatches, symbols, conventions—but I wanted it to somehow remind us of those early experiences with the internet and digital devices. I’m talking about the aesthetics of those 90s Pokemon games, for instance. They were gorgeous!

When we developed the visual identity for the project, we landed on five colours that we felt worked on a screen but also spoke about the Caribbean: white, charcoal black, a Caribbean turquoise, a flowery red, and the recognisable Cüirtopia lavender – which to me felt the most exciting, youthful, and unexpected. It was also the most legible of the colours when we overlaid the black lines of the map onto it. I wanted it to feel sweet but also techy.

The playfulness of Konpa goes back to those games as well, but also winks at those early iterations of text/chat sites on the internet. I remember a webpage where you could chat to “God”. It was hilarious and new and fresh and exciting and cool. Konpa was brought into the project, as a reminder of those moments in my teenage years where my queer identity became something I struggled with. It’s this sassy little character that interviews you, talks to you, guides you and feels like it’s alive.

Mrinmayee: Finally, I’d like to touch on this idea of counter-mapping as an act of rebellion. How do you see practices such as yours as resisting the status quo?

Regner: I think this goes back to certain points I mentioned earlier. If you come from a large continent, which usually dominates the production of knowledge, the use of resources etc., finding your location on the Cüirtopia map is a challenge. It really marks you as Other. The fact that the map’s scale always gives visibility to small islands—which get ignored, silenced, who are invaded, and colonised, and which so frequently become tax havens for the ultra-rich, who bear the brunt of climate change due to the way super-nations treat the planet—is another way.

Cüirtopia privileges small bodies of land in terms of what gets shown in a comprehensible manner. But certainly another aspect, and the most important one, is the social aspect of the map. It’s an architectural register of places produced by people’s individual stories, not by an institution or governmental agency.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

by Jerry Elengical Oct 08, 2025

An exhibition about a demolished Metabolist icon examines how the relationship between design and lived experience can influence readings of present architectural fragments.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Aug 14, 2024

What do you think?