Painting as palimpsest: a survey of Julie Mehretu’s work comes to Germany

by Srishti OjhaJul 11, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Vladimir BelogolovskyPublished on : Jan 12, 2024

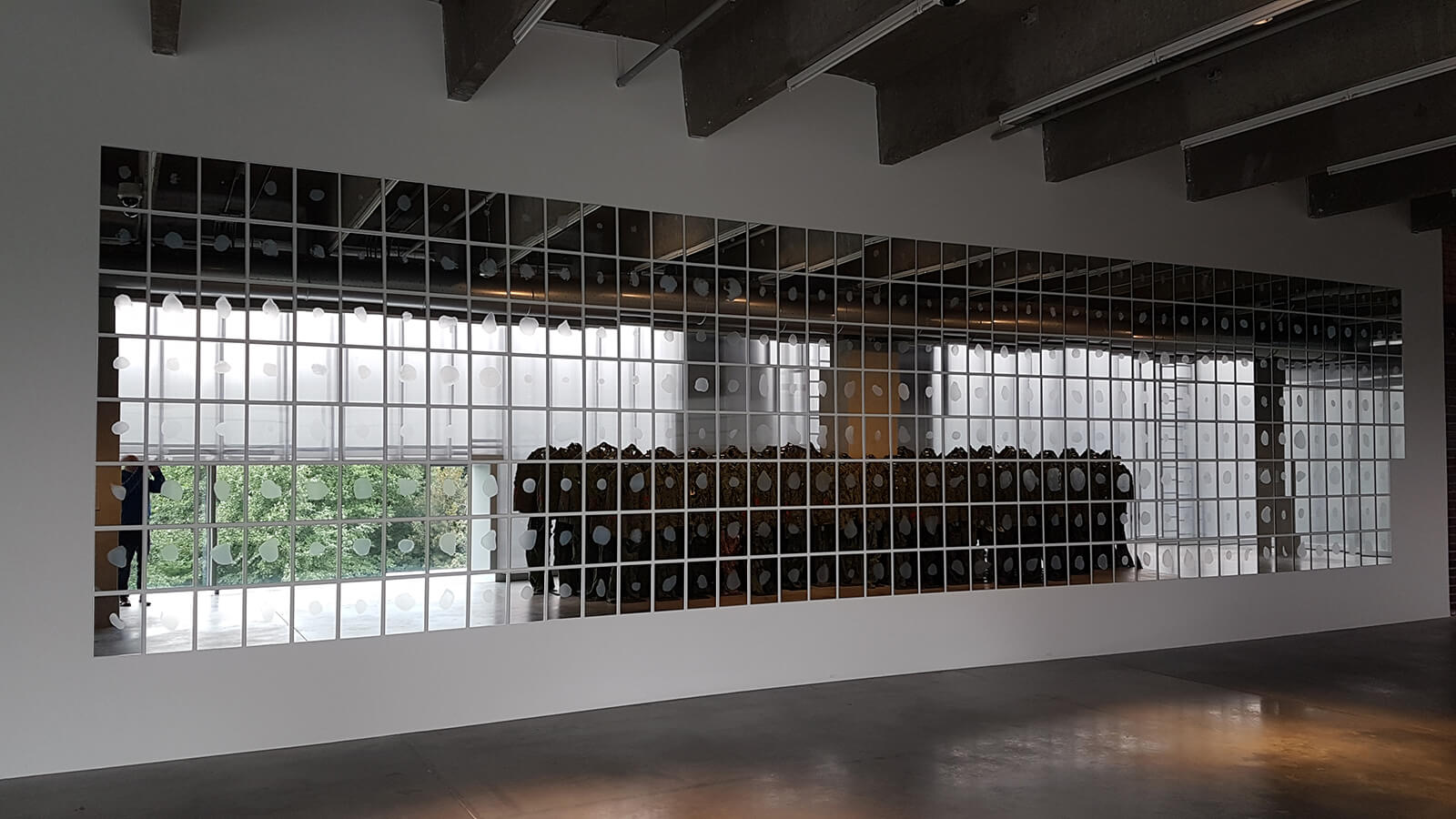

"I don’t work in a studio all day long like a scientist or a painter”—said Yuri Albert, a conceptual artist whom I talked to over a video out of his apartment in Cologne—“I just live my life, contemplate ideas, read books, and then, one day, I get a spark which may lead to developing a piece. Working for me is when something is spinning in my head." The artist informed me that he doesn’t start and finish projects. He goes back to some and initiates others, working fluidly. For example, his series of Soviet caricatures that he has been transferring on canvas is a long-term project he initiated in 1992. Among Albert’s most recent projects is an installation with 365 mirrors with imprints of his breath over a year. “It reflects our fragility as human beings— he pointed out to me—it also questions what constitutes a work of art. Would an imprint of the artist’s inner world qualify as such?”

Albert was born in Moscow in 1959. A famous French cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz was his distant relative. So, when he started sculpting little soldiers and dinosaurs out of plasteline clay, naturally, his parents saw an artistic talent in him and enrolled him in a modelling class at an art school, a local palace of pioneers. He liked it! Subsequent visits to the Pushkin Museum and reading books about the lives and art of Van Gogh, Modigliani, Repin, and his sculptor-relative, among others, led to envisioning his future as an artist. He took a drawing class at his high school. When the time came to apply for an art college, a classmate, a girl, suggested a private tutor. The tutor, Ekaterina Arnold, happened to be the wife of Alex Melamid, who with his coauthor, Vitaly Komar formed an artistic duo—Komar & Melamid; they soon immigrated to America.

Albert, 15 at the time, drew busts and painted still lifes at Melamid’s apartment where the artists had their studio. The work he witnessed at the studio was a revelation. He immediately liked it but struggled to recognise it as ‘real’ art. It was unlike anything he had ever seen before—fresh, funny, and curiously aligned with his character and love for undermining and discussing all kinds of topics and issues. Before that, he thought art was something that would be impossible or difficult to replicate. Art, he thought, could never be funny, only serious and sublime. Speaking with Komar and Melamid, his understanding of art was transformed. During those visits, he also met artists from the art group, The Nest —Gennady Donskoy, Victor Skersis, and Michael Roshal. His dialogue with conceptual artists has begun.

Soon Albert was accepted into Moscow’s Pedagogical Institute. By then he no longer dreamed of becoming Van Gogh or Modigliani. He set on becoming a conceptualist. However, he did not like his institute. There was no freedom there. Worst of all, there was no enthusiasm or inspiration. He admitted to me, “I learned nothing from them.” Nevertheless, it was while being a student there that he met many artists, including Vadim Zakharov, a future collaborator and a close friend. At the end of Perestroika, Albert started getting invitations from galleries, settling in Cologne with his family in 1990.

Albert and I spoke about nonofficial art, seeing his work as post-conceptual art, taking part in and organising apartment exhibits in the Soviet times, understanding what it meant to be a viewer, drawing connections between artworks and the artists, the need for humour and irony, and that even a conversation can be a work of art.

Vladimir Belogolovsky: You never graduated. Are you largely self-taught?

Yuri Albert: I had to go to the other side of Moscow for classes which I did not like. So, I ended up skipping many of them. Finally, when I was in my third year, I was expelled due to many absences, nothing political. [Laughs.] By then, my wife and I—I married my high school classmate, Nadezda Stolpovskaja, the girl who introduced me to Ekaterina Arnold, my first art teacher—started working on art projects together and I decided not to go back to the institute. Since then, I have been doing nonofficial art.

To make ends meet, I worked as a nightguard and took on design projects. These two jobs allowed me to work on my independent art projects until the mid-1980s. There was no need for a college degree to be commissioned to design a book cover or a set of postcards. For freelancers, all that was needed was a personal recommendation. Almost none of the Moscow conceptualists of my generation completed an art college. The older generation, such as Erik Bulatov, Ilya Kabakov, Komar & Melamid, Leonid Sokov, and others, went either to Surikov or Stroganov institutes [two leading art schools]. They are great artists who can draw and sculpt anything. But not us. Many came from theatre design, philology, engineering, and other backgrounds. For us, it is more important to work with one’s head, not hands.

VB: What did you learn from Komar and Melamid?

YA: We simply had great conversations. Most importantly, I realised that it was possible not just to make art but to work with different models of what art is. For example, what is Sots Art? Let’s imagine that some hypothetical person would do it not as hackwork but genuinely and with enthusiasm. What would happen then? It is a simple model that can turn into a whole movement, which is what they did. They also created other models that they followed. That kind of methodology was adapted by The Nest group, and that became my methodology as well. Such an approach allows artists to express their views from a distance. Art can be treated as a material. There is an irony in that. They told me, “We are the artists of the dialogue genre.”

VB: What about Kabakov?

YA: There was no direct influence and I have to underline, the idea that Moscow conceptualism was a kind of close group of collaborators is exaggerated. Kabakov, Bulatov, Ivan Chuikov, or Viktor Pivovarov, were at least 20 years older. We knew about them but we couldn’t just have a conversation. In those days you couldn’t simply knock at the door and meet them. We started crossing paths eventually through common friends. There was one work by Kabakov that made me think, an installation titled Garden; I saw it in 1979, a large empty white painting with many small paper pages with imaginary reactions by visitors. One of them said, “Let’s go from here.” [Laughs.] He had a literary approach. There is always a narrative in his work such as The Man Who Flew into Space From His Apartment. I like that. However, my approach is not literary. I don’t have characters in my works. What I do is closer to anecdotes, not novels. My works are short, paradoxical, unexpected conclusions based on certain social or political situations.

VB: How would you describe your art and what were your earliest pieces like?

YA: It is conceptual or to be more precise, post-conceptual. I am a big fan of American minimalist art which is modernist at its core. Art by the early second half of the 20th century was reduced to almost nothing, in contrast to Soviet art which maintained its traditional forms of expression. Thus, works by Soviet conceptualists were Postmodern from the start. I call this art post-conceptualism because our conceptualism came after the one in the West. So, we had to react to it. My first work was the three-litre glass jar with the air from the State Tretyakov Gallery. And the other one was titled Yuri Albert Gives Away All His Warmth to People. What is art? It is not what’s hanging on the wall, a painted cloth. Art is not in our heads either because we are looking at the walls. So, art is somewhere in between, in what is called the atmosphere of the museum or in the air. That’s exactly what I did, I captured that air inside a jar, and that became a work of art. The second idea was that art and the artist make our world warmer and better. So, I stood on the street while giving away all my warmth to people. It was simple but quite radical at the time. That was in 1978 when I was still a student.

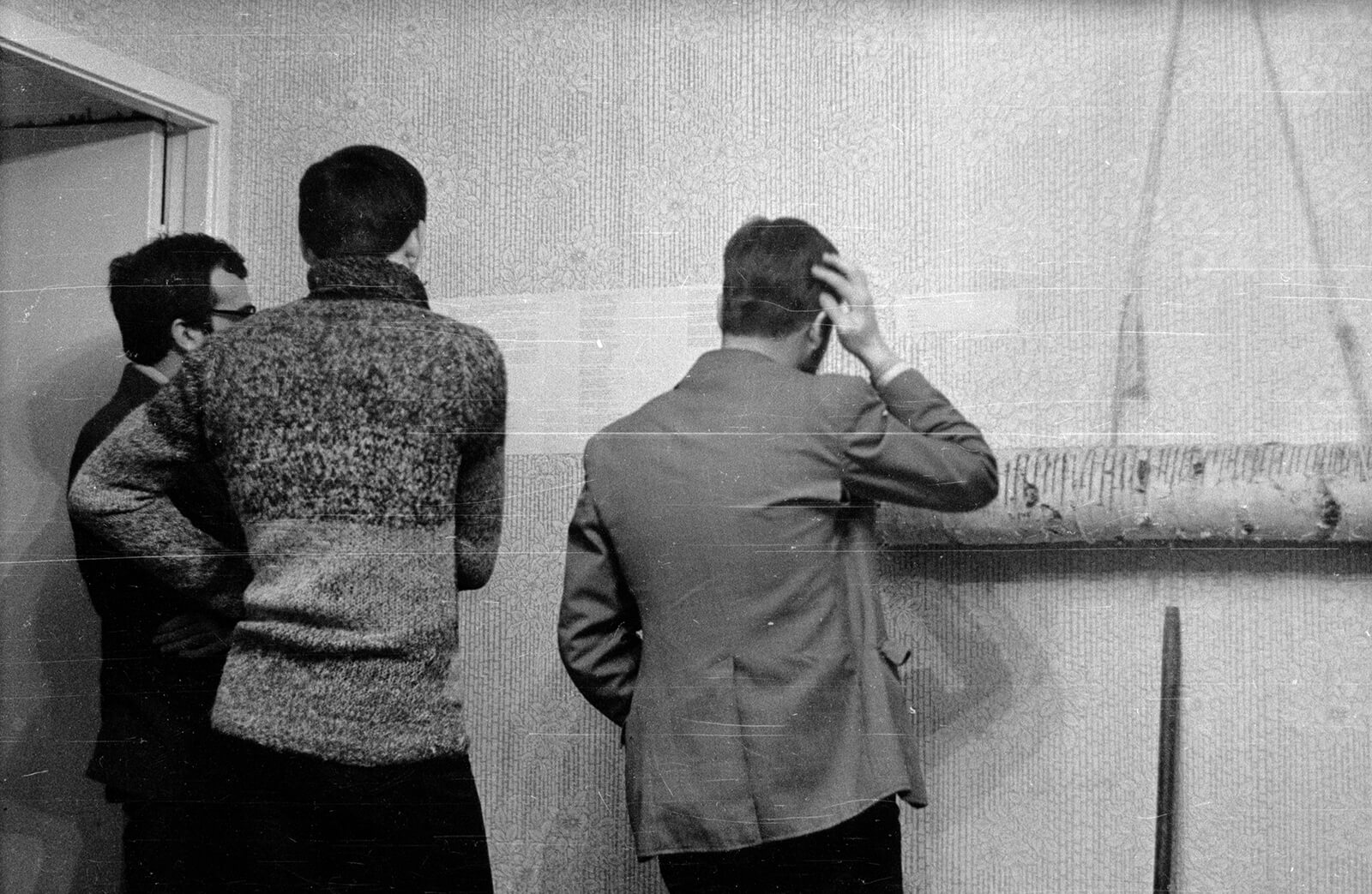

VB: Let’s talk about your first exhibitions and if you could touch on such a thing as apartment exhibits, referred to as Apt Art.

YA: Apt Art came later but shows in private apartments started in Moscow in the late 1950s. I only know of them through books when major cultural icons such as Sviatoslav Richter showed paintings by Robert Falk or Anatoly Zverev in their large apartments. There were no other places to show unofficial art. The first so-called curatorial exhibit took place in 1976 in the studio of Leonid Sokov. All works were specially selected and presented as a cohesive exhibit in a space with pure white walls. There were now well-known works by Sokov, Chuikov, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Alexander Yulikov, and Igor Shelkovsky. I found out about it from Komar and Melamid and came with several friends. At first, we were not let inside because the organisers got suspicious of why such youngsters came. [laughs.] Finally, they let us in. These artists were all with long hair and unusually dressed in jeans; they were like cowboys in our eyes. I was impressed. These people were from a different world.

Then in 1979 my wife and I decided to stage a show in our apartment. There were two of us, Zakharov, The Nest, and Skersis, who was a part of The Nest but already worked on his own. At that time, we hardly knew anyone, so no one came from the older generation. We invited everyone just a couple of days before without realising that people could have other plans. [Laughs.] Among those who came were artists from the art collective Mukhomor, Nikita Alekseev, some mathematician friends, and a few others, at most 15 people. Nevertheless, it was an important exhibition because it was then that the key figures of the new generation of conceptualists met.

VB: What did you show?

YA: Three works. One of them was about domestic help. I presented blank forms that any visitor could fill out and I would then be obliged to come to their apartments and be useful—buy bread, babysit, wash dishes, and so on. I believe it was the first socially oriented work, at least in that part of the world.

VB: Does documentation of these activities constitute art?

YA: Could be. Contemporary art is not about physical objects. Art can be a form of doing something, examining something, or having conversations. The whole notion of collecting art is more conservative than the art itself. Any skeleton is more conservative than muscles and brains. The definition of what’s art is watered down.

VB: What questions are important for you to ask today?

YA: I experiment with methodologies. I am interested in what it means to be a viewer. There are three elements in art—the artist, the art, and the viewer. In different epochs, one of these elements becomes more important than the other two. In classical times it is the artwork, regardless of who was the author and who was the viewer. In the Romantic period, an artist became more important than both the artwork and the viewer. I think now the viewer is more important than the artwork and the artist. Not because we need to please the viewers and do what they expect and want but because the viewer does a significant part of the work. To be a viewer is an important role. Now the viewer contributes even more than the artist. This is my theme; I work a lot with the viewer.

Then I work a lot with the idea of understanding contemporary art. What do people mean when they say, “I understand what art is.” What is the role of not understanding? And another theme is that for me the importance is not in the works of art but in the connections between the works and the artists. In other words, not what Cezanne painted but how he influenced the cubists. If you look at the stars, I am more interested in the gravitational forces between them than the stars themselves. The point is not to identify or create new stars but to discover new forces and connections between the ones that are already there. Any work of art becomes meaningful only when it is compared to other works of art. When we look at the portraits by Frans Hals, for example, we can’t compare them to real people. We can compare them to other works by Hals or portraits by other painters.

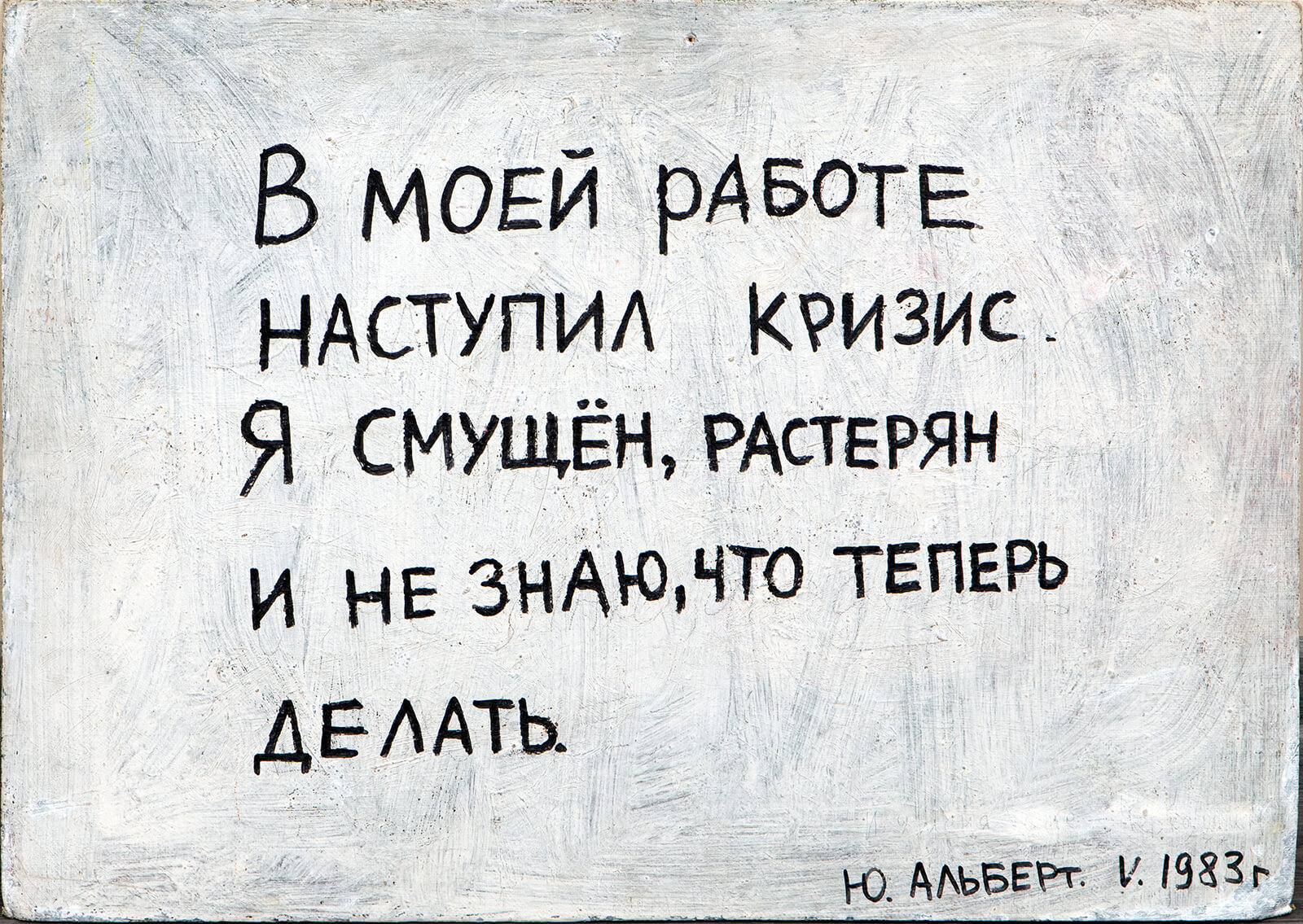

VB: You primarily work with text. How did this interest emerge and why did you choose to go in this direction?

YA: I knew about the works by Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner, so I knew I was not a pioneer. Based on my view of art, text is the most natural medium to employ to express my views. For example, one of my earlier works was a handwritten note on a piece of cardboard, “Come to my house I will be glad to show you my work.” Another listed the names of artists who influenced me. “I work under the influence of such and such artists.” So, from the start, there was this attempt to draw these connecting forces between artists. When people read these names, they immediately imagine their works and how they could have influenced me. This is what I mean by drawing connecting lines. The easiest way to identify these forces is by employing the text. Before that I had a series of works titled, I Am Not. They were done in the style of other artists in which I integrated such text as: “I am not Kabakov” or “I am not Jasper Johns.” But that was limiting. I think with the help of pure text, it can be done more effectively.

VB: You have said, “Altering someone else’s work can turn it into your own.”

YA: It is an observation. One of the most literal and radical of such examples is Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing. Then if you take such paintings as Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass you will discover that its composition is taken directly from two 16th century Italian works: The Pastoral Concert and The Judgment of Paris. He re-contextualised other artists’ subjects to make his statement. So, there is a rich tradition of artists borrowing ideas from each other.

Now the viewer is more important than the artwork and the artist. – Yuri Albert

VB: I like what you said about contradictory forces in art, “Art is a dialogue between artists, therefore, if all artists will follow any one direction and will agree with each other, all art will be destroyed. There will be a dreadful longing.”

YA: I think so. I also like to say that art is not to be looked at but to think about. This is my approach. Although, some artists disagree with me. When I interviewed Bulatov in Paris, he read this quote in one of my catalogues and poked fun at me, “Perhaps you mean that it is not important to look at YOUR art!?” [Laughs.] He was offended by this phrase because, of course, he cares greatly about the visual power of his paintings. He was very serious. [Laughs.] In any case, what I like doing in art is to be able to ask new questions. For me, the meaning of art lies in the search itself.

by Maanav Jalan Oct 14, 2025

Nigerian modernism, a ‘suitcase project’ of Asian diasporic art and a Colomboscope exhibition give international context to the city’s biggest art week.

by Shaunak Mahbubani Oct 13, 2025

Collective practices and live acts shine in across, with, nearby convened by Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli and Bergen School of Architecture.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

![[L] Portrait of Yuri Albert; [R] Yuri Albert sleeps at the opening of the exhibition “Metamopheus” of the Group Cupid (Y. Albert, P. Davtjan, A. Filippov, V. Skersis), 2011 | Yuri Albert | STIRworld](https://www.stirworld.com/image.php?width=1920&height=1080&image=https://www.stirworld.com/images/article_gallery/-l-portrait-of-yuri-albert-r-yuri-albert-sleeps-at-the-opening-of-the-exhibition-ldquo-metamopheus-rdquo-of-the-group-cupid-y-albert-p-davtjan-a-filippov-v-skersis-2011-yuri-albert-stirworld-240109061002.jpg)

by Vladimir Belogolovsky | Published on : Jan 12, 2024

What do you think?