The eArthshala campus signifies an evolving view of sustainability in Indian design

by Mrinmayee BhootMar 21, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Mrinmayee BhootPublished on : Jun 10, 2024

"We are a community of air,” one of the brothers soliloquizes at the end of All That Breathes (2022). The documentary, directed by Shaunak Sen about the entanglement between humans, non-humans, and the environment set in New Delhi—a city I have called my home for seven years—provides a lens to reflect on the city’s extremely poor air conditions (often compared to a ‘gas chamber’). Since 2013, New Delhi has reported PM2.5 levels of 200 μg/m3, considerably making it one of the worst polluted cities in the world. The documentary somberly depicts how we have all had to adapt in some way. But with a phenomenon that seems as universally atmospheric as air pollution, the question we should be asking is: do we understand pollution at the scale of the personal beyond the enigma of sustainability? What do PM and AQI values mean for communities to be able to take action? Can we even begin to build resilience at the grassroots?

New Delhi-based Architecture for Dialogue is trying to answer these questions, with their research and practice centred on the role of architecture in building pollution and climate resilience. Currently, the designers are working on a prototype for BreatheEasy, a project that proposes a retrofit-based and cost-effective approach to housing upgradation in India. The project which was among the winners of the Redesign Everything Challenge furthers the practice’s inquiry into architectural responses to surmounting toxic air in the capital city. In a climate where air pollution is understood only through the lens of policy, STIR spoke to the Indian architects about their work. The conversation touched on the idea of building resilience through architecture, the idea of air as a medium that binds us all and how we respond to it and the practice’s goals with BreatheEasy. Below is an excerpt of a conversation that considers how and what we breathe.

Our inquiry started with this: what would resilience mean, architecturally speaking, to air pollution? –Abhimanyu Singhal, Partner and Research Lead of Architecture for Dialogue

Mrinmayee Bhoot: Where and how did you initially start thinking about responding to air pollution?

Abhimanyu Singhal: Our inquiry into air pollution has been a three-year interest now. It started with us trying to understand the role of architects and architecture in building resilience against air pollution. We've been in New Delhi for most of our lives. And it comes out as an obvious question. How do you attach what you do in your workplace to problems that you face in your house? So, we produced an art installation in 2022 called My House is Ill with Khoj Studios Residency. It was backed by a series of experiments that we had conducted in Khirkee Village, which explored the intersection between air and everyday spaces.

Some questions we were interested in were: how does the air in different rooms interact with the air outside? What causes airflow? What causes the prevalence and intensity of air pollution in indoor spaces? As much as we talk about air pollution at a city level, wearing masks when you go outside and all of these AQI numbers that flash on public boards and our apps, we are not really aware of it indoors. Our inquiry started with this: what would resilience mean, architecturally speaking, to air pollution? Since then, we have been engaged in working with the local community, trying to understand what air pollution means in different kinds of households and how it might have a compounding effect overall.

Depanshu Gola: Something I would add is that as architects, we have been taught how buildings are designed and that different knowledge systems respond to different climatic conditions. But with something like air pollution, we are still grappling with our knowledge on the subject. And interventions tend to be focused at the level of policy or urban design.

Our idea was to engage with air pollution in a space that we can comprehend. And that's where we thought homes were a great point to start. And then, we wanted to see if we could figure out some existing knowledge systems, historical practices, or traditional architectural techniques that already operate in a way to help houses adapt to air pollution.

Mrinmayee: Could you tell us more about your research and how it evolved into BreatheEasy? Perhaps you could stress on your grassroots approach a little.

Depanshu: The first step would always be to understand a problem further. That’s where this project started as well, with the Khirkee Air Lab, which was supported by the Prince Claus Fund and Khoj International Artists’ Association. For it, we took up an apartment and through different experiments tried to see what are the different ways of visualising and understanding air mechanisms: how air moves and what are the components of air pollution. Through particulate matter (PM) sensors, we looked into our spaces and saw how these values change during the day during different activities.

Then the question was how to put out this data we had collected about PM particles or Air Quality Indexes (AQIs) in different forms, which goes beyond these incomprehensible numbers that we constantly see. We were curious to understand how the project can engage you further. Or maybe give you more action points? With the information available, do you feel you can do something about it? As we mentioned, this lab turned into a public exhibition at Khoj.

Abhimanyu: The next step involved us talking to a lot of organisations who were working on air pollution and as a result, the NGO Asar Social Impact Advisors invited us to do a spatial study in the settlement of Madanpur Khadar, which is near Okhla in New Delhi.

There, we started with a qualitative ethnography study, where we looked at how household routines and behaviours intersect with air pollution and its different sources. We got to understand how people seem to deal with it, or where they cannot protect themselves. We talked to women—there was a gender focus to the study—to look at how the effect of the chullah or the effect of waste burning in the neighbourhood compounds the pollution. And we came up with different kinds of design responses to it, both at the household and community level. The question was always, what could spatial solutions mean?Through that study, we arrived at the idea of retrofitting. In the settlement of Madanpur Khadar, which is predominantly low-income households, any upgrade to someone’s house comes with a lot of saving and planning, hence retrofitting. The question we wanted to focus on was, how do you work with existing structures to improve ventilation or reduce exposure in indoor built environments?

At the end of 2023 and our work with Asar and the Cleaner Air and Better Health (CABH) programme, we had a few passive design solutions that we wanted to test, which is when we got the fellowship from Godrej Design Lab, allowing us to start work on prototypes.

Mrinmayee: I also wanted to understand your design process and the prototype you have created. You mention that you are working with vernacular architectural systems. Could you elaborate on that?

Abhimanyu: I'll start with a couple of findings that we had from the field last year. We noticed that these houses are on tiny plots of land and have to face hostile conditions from the outside, criminal activities, pests, the issue of privacy etc. Most importantly, the households that we studied weren't really designed for ventilation, with everything being blocked to prioritise security.

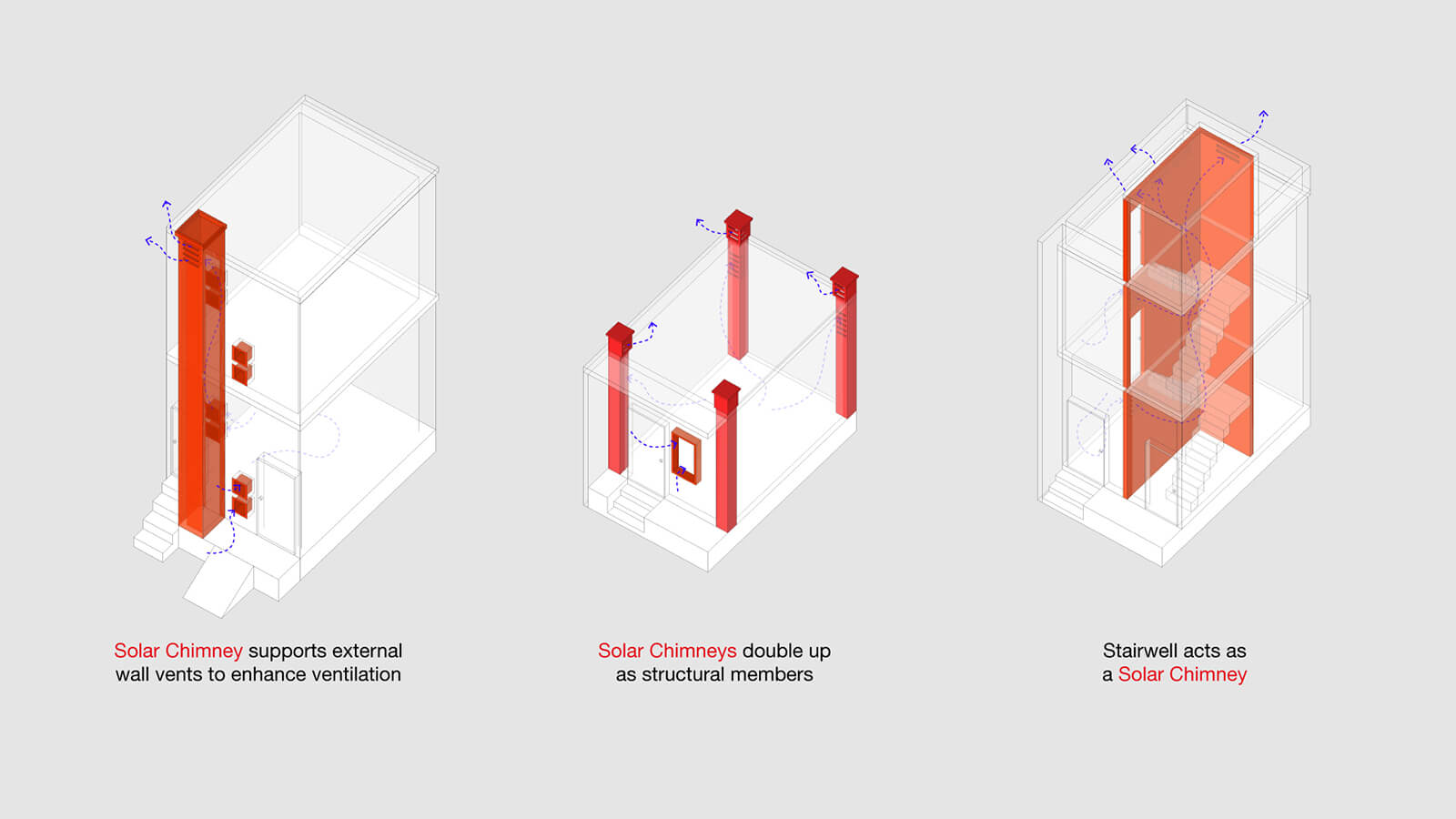

There was an opportunity to address air pollution or reduce exposure to it by reducing the intensity of pollution. When you cook inside, irrespective of the fuel that you use, there's a high amount of indoor air pollution. We tested this by placing monitors inside houses to map pollution levels across a 24-hour timeline and see how cooking or other sources of pollution affect the space and how long this pollution lingers. Ventilation turned out to be a starting point to help alleviate some of the exposure and adverse effects on residents’ health. Due to poor electricity, exhaust systems are not reliable, so we looked at passive ventilation mechanisms. We asked ourselves, how can we leverage vernacular construction techniques like wind catchers or solar chimneys and improve ventilation? While experimenting with different types of wind catchers/solar chimneys, we realised that wind catchers need a lot more wind speed than Delhi actually has.

That narrowed it down to solar chimneys. Our first step then was to validate this principle. Theoretically with solar chimneys, there is a stack effect that a heated chimney effect would create and then there would be negative pressure that would suck the air out of the household, eventually creating a cross-ventilation mechanism. To test this, we conducted some simulation studies and smoke tests on a 1:10 scale model, to be able to see whether what we are saying and what we hope to achieve is actually happening. And we've been on the right track because we are actually getting great results. This is where we are at currently and how traditional wisdom sort of found its way into the project.

In the prototyping stage, what is key for us is to constantly work with people instead of for people. –Depanshu Gola, Design Lead and Partner at Architecture for Dialogue

Mrinmayee: What have some responses been like?

Depanshu: I think we have been fortunate enough that when we were working on this project and trying to figure out some intervention that could have been possible in-between spaces or air pollution, there were already a group of women with an organisation called Changemakers, who were conducting knowledge sharing workshops around the general topic.

Apart from that, we have been having multiple interviews and engaging with them to answer questions like: what are these realities or problems that they face? Are there any existing solutions? Or what are some ways they tackle the problems even now? And right now, in the prototyping stage for the sustainable design, what is key for us is to constantly work with people instead of for people.

For example, if I could give you an anecdote, with the kind of solution we are talking about i.e. retrofit solar chimneys, say in a house there is this front façade with blocked/open doors and windows, the question is how do we intervene? We have gotten responses from the residents that out of two to three options where one chimney is coming to the ground floor, it could also start on a door lintel level. They say, [but it would be better] if it started from the lintel level because we use the veranda space. These are certain nuances and it allows us to keep refining our design by actually checking with the people we are designing for rather than our assumptions.

Abhimanyu: Adding to that, because of this crisis, even though people face it every day of their lives, women are the most affected. In interacting with them, we heard them report symptoms like burning eyes, coughing, the interior surfaces of their houses having deposited black soot and so on. But, because this still lies at the bottom of their priorities for sustenance, it is difficult to go to the community and say, we have a solution to a problem that you don't even register as a problem. As a result, this project has been a parallel exercise of figuring out the value-add for the community. We go to the community once every month, make it a point to catch up, take feedback and if not, co-create, have participatory workshops and activities that help us in our design process. In those activities, it's been a constant effort from our end to communicate what we are finding, to be able to make air pollution as transparent as it is to us at least. Therefore, be able to establish a need for a solution.

And the chimneys will have positive effects, no matter if you're cooking or not, you are getting immediate comfort in terms of your indoor environmental quality. So these are some adjacent themes that we talk about with the community. These have helped bring or gather some interest in the community for us to be able to prototype a solution.

When asked what comes next, Depanshu was hopeful that their research might inspire a new way of doing things. “How can one build their houses in a way that actually responds to air pollution in some way?” he questioned. It’s a constant process, as he suggests. “The idea would be to understand the value of this process; these cycles of research and design where you learn something, test certain ideas and keep refining it.” Every life form adjusts to the city now, the question is what more can we do?

by Bansari Paghdar Oct 16, 2025

For its sophomore year, the awards announced winners across 28 categories that forward a contextually and culturally diverse architectural ecosystem.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 14, 2025

The inaugural edition of the festival in Denmark, curated by Josephine Michau, CEO, CAFx, seeks to explore how the discipline can move away from incessantly extractivist practices.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 10, 2025

Earmarking the Biennale's culmination, STIR speaks to the team behind this year’s British Pavilion, notably a collaboration with Kenya, seeking to probe contentious colonial legacies.

by Sunena V Maju Oct 09, 2025

Under the artistic direction of Florencia Rodriguez, the sixth edition of the biennial reexamines the role of architecture in turbulent times, as both medium and metaphor.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Mrinmayee Bhoot | Published on : Jun 10, 2024

What do you think?