Girls on swings, transforming art history: Cecily Brown’s Themes and Variations

by Leah TriplettApr 04, 2025

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Eleonora GhediniPublished on : Jul 23, 2024

"Time is the only thing one has. Time is valuable.” These words by the Sámi artist Britta Marakatt-Labba invite us to leave behind the day-to-day of life and immerse ourselves in her delicately embroidered landscapes. However, under their surfaces, we should not expect to discover only idyllic, temporary escapes. Blurring the boundaries between myth and reality, Marakatt-Labba speaks of a whole culture long left on the margins: the Sámi Indigenous people, known as the inhabitants of a wide territory which extends across Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. A great occasion to explore her work is the major exhibition Britta Marakatt-Labba. Moving the Needle, which is currently on view at the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo. Curated by Randi Godø and Anne Sommerin Simonnæs, the exhibition reconstructs the artist’s career from the early 1970s until today, presenting diverse media such as sculpture, installation and a wide selection of textile art pieces. The embroidered works are the real protagonists: in a conversation with the curator in the exhibition catalogue, Marakatt-Labba defined them as “a leap from everyday life to the cosmos.” Her words resonate with the current reexamination of textile art as a discipline.

Marakatt-Labba was born in a reindeer-herding family in Idivuoma, Sweden, in 1951. She grew up between the Norwegian and Swedish sides of the Sápmi territory. During her studies at the Högskolan för Design och Konsthantverk (School of Design and Craft) at the University of Göteborg, embroidery became her favourite medium (she graduated with a degree in Textile Art in 1978). That same year, she was one of the founding members of the radical art collective Mázejoavku (Máze Group); the main purpose of the collective was to claim the Sámi identity through contemporary art - and the relation between art and activism has always been deeply rooted in their creative process. Throughout the last decade, Marakatt-Labba gained broader international recognition. After having been included in documenta 14 in Kassel in 2017 and the Venice Art Biennale 2022, her work is now in an ideal setting within the Nasjonalmuseet as the museum offers a significant overview of textile art and design from the Nordics. Walking across its permanent collection, we can admire works by great masters of this field, such as the tapestry innovators Frida Hansen (1855-1931) and Hannah Ryggen (1894-1970). Marakatt-Labba’s exhibition also extends a lineage of exhibitions in an institution where textile art and material culture have played an important role. Previously, the museum has shown Louise Bourgeois. Imaginary Conversations – and Oltre Terra. Why Wool Matters by the renowned design studio Formafantasma, both in 2023.

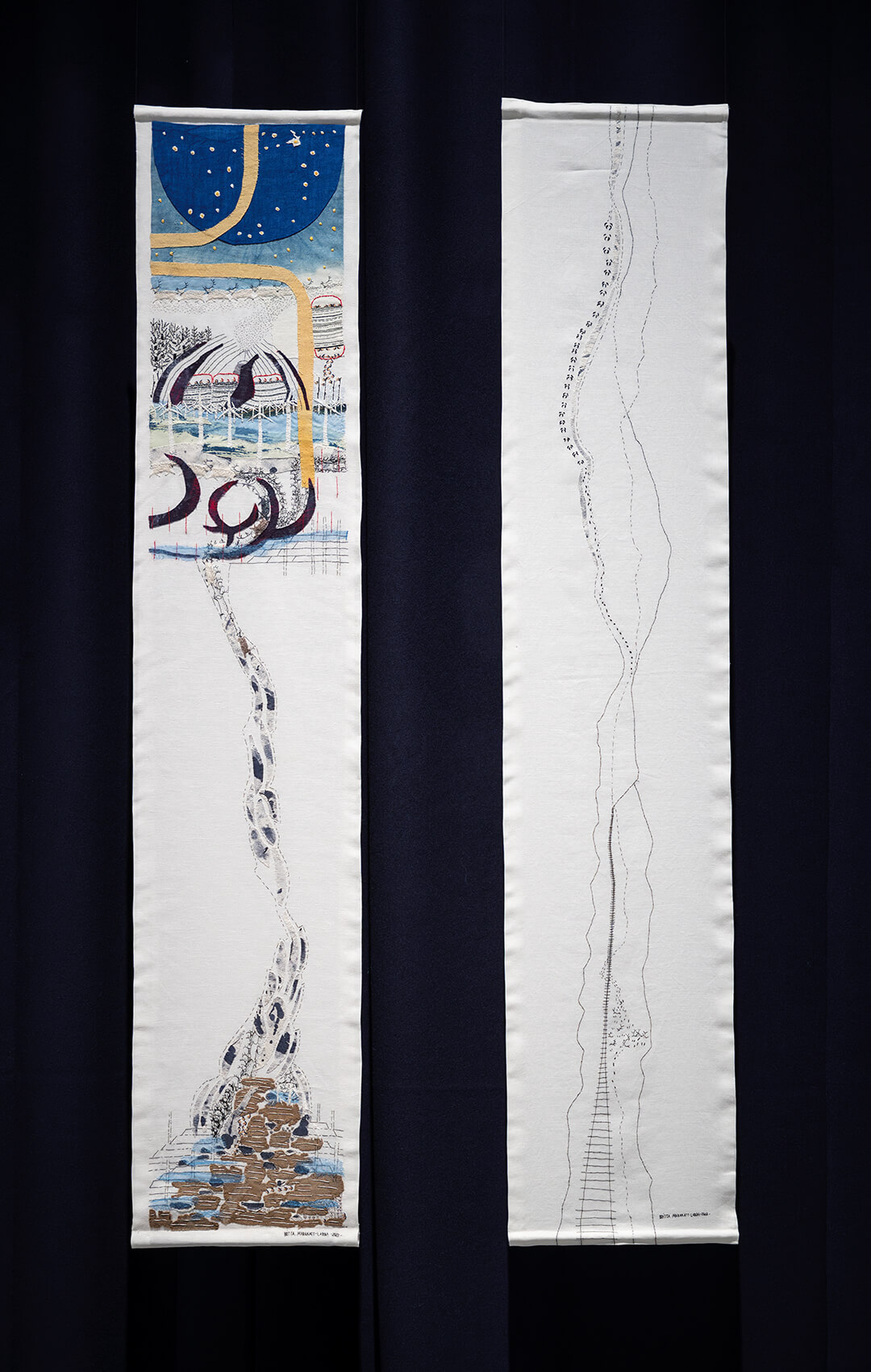

In Marakatt-Labba’s language, stitches are the grammar and the linen canvas is the blank page. The white vastness of the Sápmi landscape is the main protagonist of her storytelling. Here, at the edge of the Arctic, the Sámi people have been adapting to a hostile environment for millennia – an ancient balance that is increasingly at risk due to climate change and the exploitation of local resources. Marakatt-Labba’s textile piece Luođđat (Tracks, 2023), which was appositely commissioned for this exhibition, emblematically represents the fragility of this environment. Embroidered on the front and back, this vertical work puts, in contrast, two almost antithetical kinds of traces – on one side, animal tracks on snowy ground that the Sámi people can skillfully recognise, and on the other side, the signs left by recent forms of human industrialisation.

The Italian anthropologist Gianluca Ligi suggests that the Sápmi has often been idealised as an "ageographic concept", as opposed to a physical location. Marakatt-Labba distances herself from this idealisation, facilitating an original encounter between activism and duodji, a traditional Sámi handicraft. Her aesthetics defies the utopic representation of her homeland often seen in Western imaginings. Her non-violent “weapon” is what the British art historian and psychotherapist Rozsika Parker (1945-2010) would have defined as a subversive stitch.

At the core of the Oslo exhibition, the iconic 24-metre-long embroidery Historjá (2003-2007) is displayed like a luminous ribbon suspended in darkness, transporting the viewer into an endless circular movement that is based on the cyclical conception of time among the Sámi. Like in a musical score, the rhythm of the composition is created by the alternating of birch trees, human figures, reindeer and other creatures of the tundra environment. In Marakatt-Labba’s visual vocabulary, we can perceive the echo of the shamanistic drums and their ornaments, while the palette chosen for the yarns and the appliqué fabrics is a tribute to the gákti, the traditional Sámi costume, as well as to the landscape of Sápmi. Blurring the lines between past and present, Historjá is a masterful synthesis of history, mythology and everyday life, where the silent flow of events can also be abruptly interrupted by tragic, violent events.

Garjját (The crows, 1981) emblematically describes the oppression of the Sámi people throughout their history, particularly since the beginning of the 1970s, when the Alta conflict began in northern Norway. Despite peaceful resistance against the construction of a hydroelectric power plant, the project was completed in 1987 after the rights of the Sámi demonstrators had been repeatedly violated. In Garjját, this violation is embroidered as a procession of crows bursting into the scene and gradually transforming into police forces. Marakatt-Labba’s historical references do not merely concern the Sámi resistance, as we can see in the installation Dáhpáhusat áiggis (Events in time, 2013), made with original burlap flour sacks from the Nazi occupation of Norway during the Second World War. The work offers a reflection on the tragedy of Utøya (2011) and, therefore, on the ebbs and flows of European history.

In conclusion, we might mention works such as Lodderáidaras (The Milky Way, 2022), where Sámi people, their land and the sky are encapsulated within a single unit which is hovering over a blue velvet firmament. This bright representation of Sámi cosmology reminds us of the words used by the Sámi poet Nils-Aslak Valkeapää (1943-2001) to describe the Sápmi territory (paraphrased in translation): here is a bit of every single thing and if you have eyes to see you don’t need to search.

by Sunena V Maju Mar 11, 2026

The 82nd Whitney Biennial 2026 is a group show that reflects the ‘turbulent existential weather’ of the United States today.

by Srishti Ojha Mar 06, 2026

The British artist’s solo exhibition, ZOT at Varvara Roza Galleries in London, takes a postwar, postmodernist peek behind the curtain of artist studios.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Feb 27, 2026

Are You Human? brings together a staggering list of works that strive to question the consequences of our pervasive digitality but only engage with it superficially.

by De Beers Feb 27, 2026

The immersive installation by De Beers, featuring artist Lakshmi Madhavan, framed natural diamonds through art, nature and human expression at India Art Fair 2026.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Eleonora Ghedini | Published on : Jul 23, 2024

What do you think?