Advocates of change: revisiting creatively charged, STIRring events of 2023

by Jincy IypeDec 31, 2023

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Ranjana DavePublished on : Apr 25, 2024

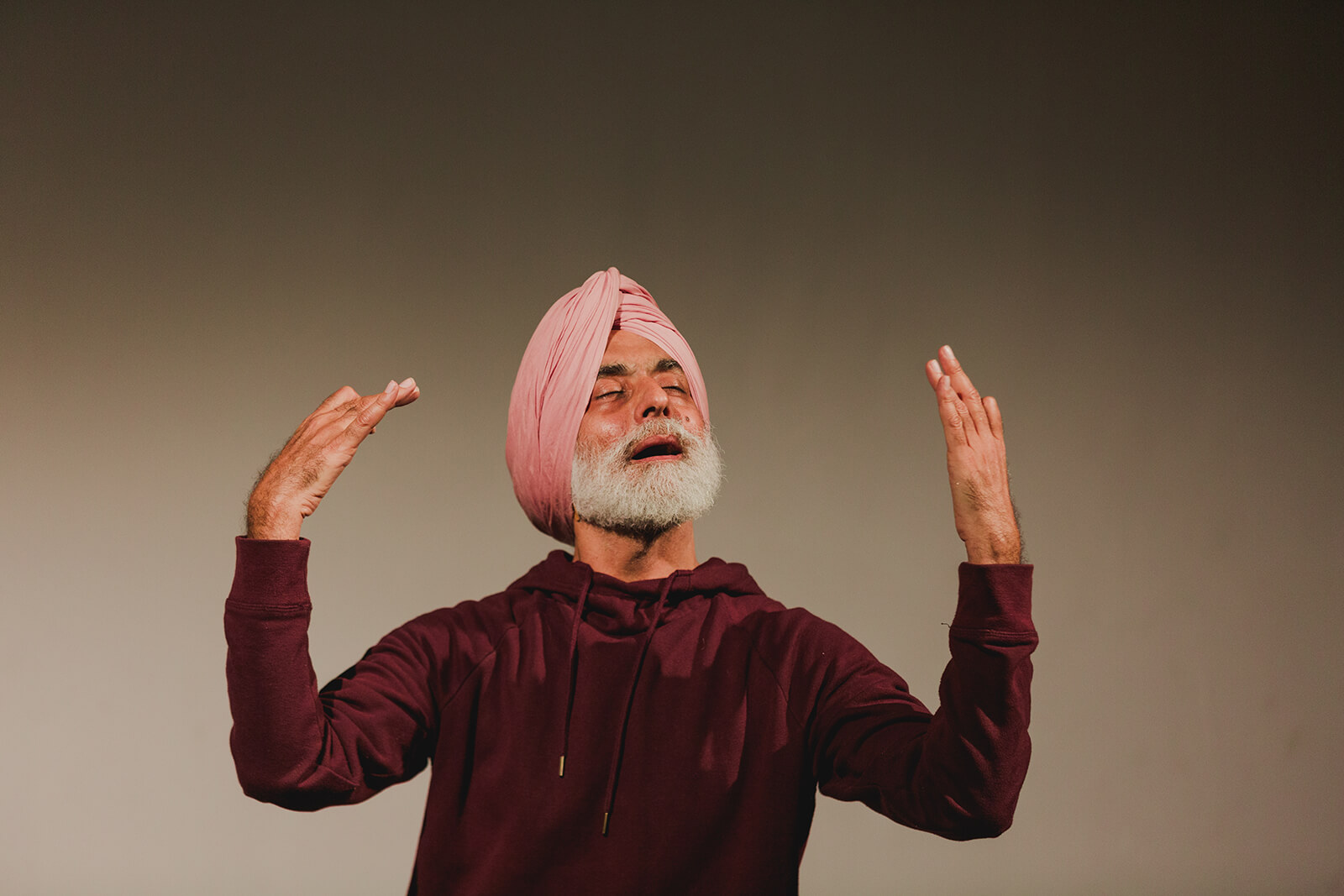

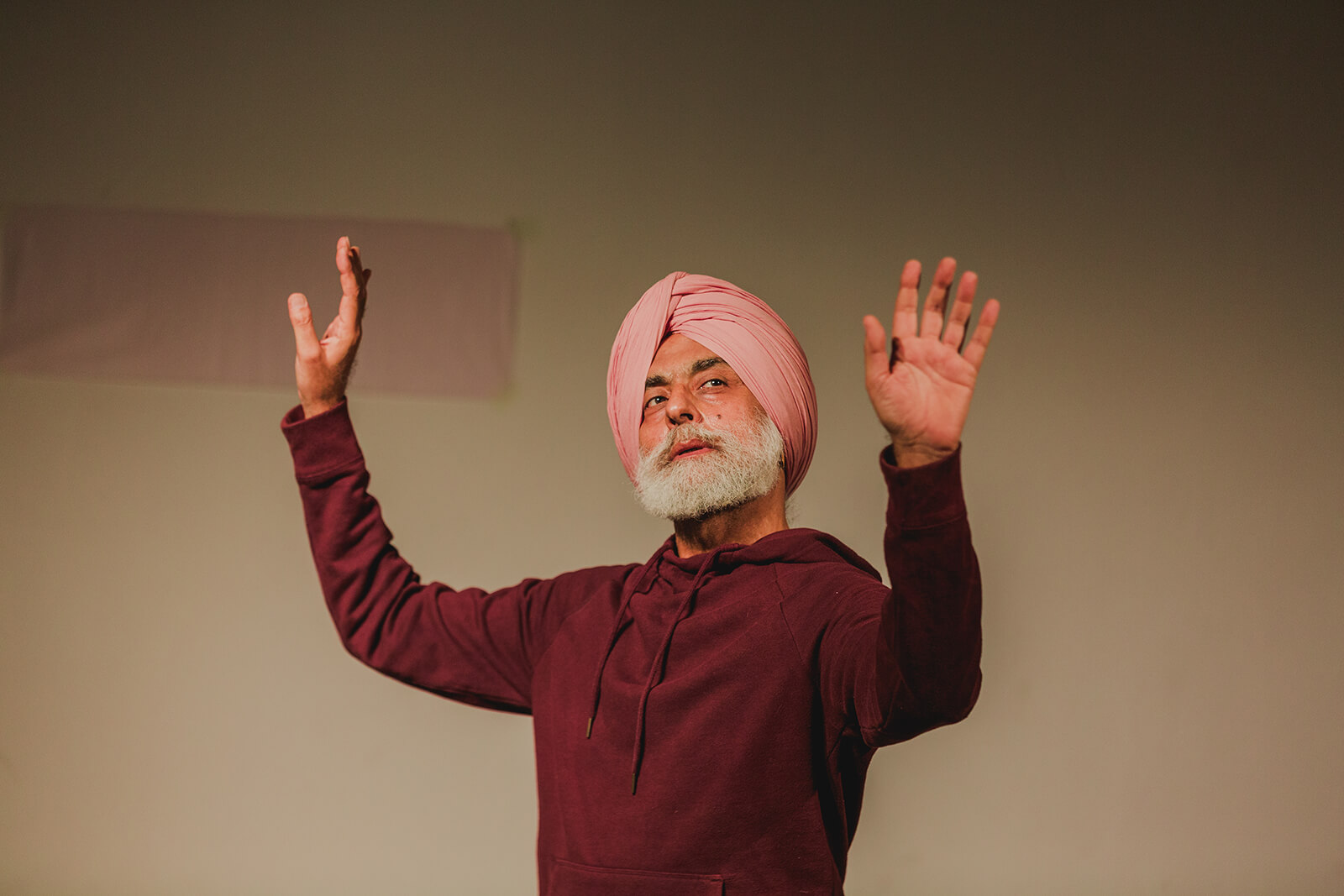

As the audience files into the makeshift performance space—a photographer’s studio—they pass a moving body, its buoyant limbs extending into space. Never frozen, yet eerily silent, his limbs defy gravity, straining upward and outward. Your gaze travels up to the performer’s face, recognising the dancer and choreographer Navtej Johar, in the opening phrases of his solo performance work, Tanashah (Dictator). Johar continues moving as people go through the awkward motions of settling into the small space. Tanashah is based on Johar’s training and performance research and the jail diaries of the 20th century Indian revolutionary Bhagat Singh. First created for the Serendipity Arts Festival 2018, Johar has continued to develop the work, traversing an expansive field of music, movement and speech. In March 2024, he performed as part of Little Stint, a weekend of performances and screenings organised by Delhi-based arts initiatives WIP Labs and Oddbird Theatre.

Little Stint highlights the work of independent artists in the performing arts and film, organising events in intimate venues that spark easy exchanges between audiences and artists. In this version of Tanashah, Johar worked with musician, composer and sound designer Baan G, who created a responsive sound design on stage, playing pre-recorded samples with live layers. The personal, historical and political converge in Johar’s performance—the Punjabi dialogues he delivers in the role of Bhagat Singh are interspersed with padams (slow narrative compositions) from the Bharatanatyam repertoire. Johar invokes familiar and unfamiliar landscapes—the rich red soil of the Konkan and the Deccan plateau on his train journeys to Kalakshetra, and the lush greenery of Punjab, where Singh’s name is remembered in every village. Johar doesn’t just ‘portray’ Singh; he locates the revolutionary in his body, his spine coming alive with Singh’s quiet dignity. External markers of the ‘performance’ are sparse; Johar is clad in a sweatshirt and pants, and scruffy dark socks. At one point, he wraps a turban on his head, clenching one end between his teeth as he wraps the fabric in taut circles. The audience avidly follows the process, the tension of its gaze saturating the air in the room.

Singh was arrested for shooting and killing the British police officer John Saunders in Lahore, avenging the death of Indian nationalist Lala Lajpat Rai. He identified as an atheist and socialist, writing the essay Why I Am an Atheist to explain his position. In his text, Singh wonders if denying the existence of god is a form of vanity. He knows that a death sentence is around the corner, but refuses the suggestion that he might turn to prayer as a last resort. If death is inevitable, it is almost as if he desires it—Johar sets up a comparison between desire and longing, turning to a padam about a man separated from his beloved. Rama Rama pranasakhi, the singer slowly intones, stretching out each syllable to match the slowness of Johar’s movement.

Johar is a veteran of the independent dance scene in New Delhi, with a sustained artistic and pedagogic practice across studio and university settings. He trained in Bharatanatyam at Kalakshetra and Patanjali yoga at the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram, both in Chennai. Johar’s movement practice investigates the differences between the codified fixity of classical dance and the self-reflexive environment of yoga. He evolved a somatic, or embodied, practice that attunes the mover to sensory prompts manifesting within the body. These random prompts inform other performative and choreographic choices—shapes, postures, breath, gaze and affect among them. Tanashah draws on this somatic practice, moving away from virtuosic choreographic strategies to source movement from the emotional landscape of the piece.

Over six years of revisiting the piece, Tanashah has become a choreographic foil for Johar’s artistic beliefs and movement methodology. He speaks of his resistance to the superficial transmission of movement in classical dance, where the body is constantly playing catch-up, attempting to imitate ‘ideal’ shapes without necessarily going through the longer process of locating those shapes in the body.

Johar’s pedagogic vocabulary is not prescriptive; movers are not instructed to perform specific actions but are offered open-ended prompts grounded in experience and action that allow them to find movement in the body. This pedagogic research comes through in Tanashah; occasionally, Johar might use gestures from the narrative vocabulary of classical dance—a deer, a single-hand gesture, two fingers glued to the thumb, with the index finger and little finger sticking out to portray its ears—or a gently held wrist, with the thumb and two fingers coyly spanning its circumference. These gestures are what the body remembers.

The audience watches him perform, but Johar also witnesses himself forming and manifesting movements in response to narrative and sensory prompts. His absorption is all his own—he is seeing and being seen.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 10, 2025

Directed by Shashanka ‘Bob’ Chaturvedi with creative direction by Swati Bhattacharya, the short film models intergenerational conversations on sexuality, contraception and consent.

by Asian Paints Oct 08, 2025

Forty Kolkata taxis became travelling archives as Asian Paints celebrates four decades of Sharad Shamman through colour, craft and cultural memory.

by Srishti Ojha Oct 08, 2025

The 11th edition of the international art fair celebrates the multiplicity and richness of the Asian art landscape.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Oct 06, 2025

An exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art delves into the clandestine spaces for queer expression around the city of Chicago, revealing the joyful and disruptive nature of occupation.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Ranjana Dave | Published on : Apr 25, 2024

What do you think?